Franco-Mongol alliance

The Franco-Mongol alliance existed during a period of the 13th century in which the Frankish kingdoms of the Levant (also known as Crusader States)[1] and the countries of Western Europe allied with the Mongol Ilkhanate based in Persia, in order to combat their common Muslim enemy in the Middle East. During that period, the Mongols had numerous exchanges of letters and embassies with European monarchs, leading to diplomatic and military alliances against the Muslim realm and in favor of Christianity. Contacts started when Gengis Khan sent emissaries to the Franks in the Middle-East, and the first attempt at a military collaboration took place during the Crusade of the French king Louis IX, between 1248 to 1254. In 1260, most of Muslim Syria was conquered by the joint efforts of the Franks, the Armenians and the Mongols, only to be retaken by the Egyptian Mamluks when the Mongols had to remove most of their forces due to conflicts in Central Asia. The Mongols again invaded Syria several times, in 1281, 1299, 1300, 1303 and 1312, most of the time in alliance with the Christians. This difficult alliance, over considerable distances and large cultural differences, bore little fruit however, and ended with the victory of the Mamluks and the total eviction of the Franks from the Middle East by 1303, and a treaty of peace between the Mongols and the Mamluks in 1322.

Religious affinity

The Mongols had been proselytised by Christian Nestorians since about the 7th century and many of them were Christians.[2] Many Mongol tribes, such as the Kerait, the Naiman, the Merkit, and to a large extent the Kara Khitan, were Nestorian Christian. Overall, Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions, and typically sponsored several at the same time.

Rabban Bar Sauma testified to the importance of Christianity among the Mongols, during his visit in Rome in 1287:

"Know ye, O our Fathers, that many of our Fathers (Nestorian missionaries since the 7th century) have gone into the countries of the Mongols, and Turks, and Chinese and have taught them the Gospel, and at the present time there are many Mongols who are Christians. For many of the sons of the Mongol kings and queens have been baptized and confess Christ. And they have established churches in their military camps, and they pay honour to the Christians, and there are among them many who are believers."

— Travel of Rabban Bar Sauma, p.174[3]

Some the major Christian figures among the Mongols were: Sorghaghtani Beki, daughter in law of Genghis Khan, and mother of the Great Khans Möngke, Kublai, Hulagu and Ariq Boke, who were also married to Christian princesses;[4] Oroqina Khatun, wife of Hulagu and mother of the ruler Abaqa; the Mongolian Khan Sartaq; the Naiman Kitbuqa, general of Mongol forces in the Levant, who fought in alliance with Christians. Marital alliances with Western powers also occurred, as in the 1265 marriage of Maria Despina Palaiologina, daughter of Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, with Abaqa. An Ongud Mongol was the highest authority (Patriarch) of the Nestorian church from 1281 to 1317 under the name Mar Yaballaha III.[5]

On the other hands, the Mongols had been in conflict with the Muslims for a long time since the Muslims advanced in eastern Central Asia in the 8th century (Battle of Talas), possibly explaining their partiality against them.

Other Mongols, such as the ruler of the Golden Horde Berke were on the contrary highly favourable to Islam, leading to conflicts between Mongol clans, as in the Berke-Hulagu war.

Early contacts (1209-1244)

Gengis Khan himself was a Shamanist, but was tolerant of other faiths, and was especially fond of Christianity. His sons were married to Christian princesses, of the Kerait clan, who held considerable influence at his court.[6] The Nestorian Christians of Central Asia were generally highly favorable to him[7] and hoped for an alliance between the Mongols and Western Christianity.

The Mongols first invaded Persian territory in 1220, destroying the Kwarizmian kingdom of Jelel-ad-Din, and then conquering the kingdom of Georgia ruled by George IV, who submitted to him, soon followed by Hetoum I, king of the Armenians, who became a longtime advocate of the Mongols.[8]

In a letter dated June 20th, 1221, Pope Honorius III commented about "forces coming from the Far East to rescue the Holy Land".[9]

Genghis Khan then returned to Mongolia, and Persia was reconquered by Muslim forces,[10] until a huge Mongol army again came in 1231 under the general Chormaqan. Chormaqan ruled over Persia and Azerbaijan from 1231 to 1241.[11] In 1242, Baichu further invaded the Seldjuk kingdom, ruled by Kaikhosrau, in modern Turkey, again eliminating an enemy of Christiandom.[12]

Papal overtures (1245-1248)

The Mongol invasion of Europe subsided in 1242 with the death of the Great Khan Ögedei, successor of Genghis Khan. In the Holy Land, the Christians were confronted with a disaster when Jerusalem fell to the Khawarizmi Turks with the complicity of the Ayubids in 1244, leading to the near-destruction of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[13] This event prompted Christian kings to prepare for a new Crusade, decided by Pope Innocent IV at the Council of Lyons in June 1245, and revived hopes that the Mongols, who had Christian princesses among them and had brought so much destruction to Islam, could become allies of Christendom.[14][15]

In 1245, Pope Innocent IV issued bulls and sent an envoy in the person of John of Plano Carpini (accompanied by Benedict the Pole) to the "Emperor of the Tartars". The message asked the Mongol ruler to become a Christian and stop his aggression against Europe. The Khan Güyük replied abruptly in 1246, demanding the submission of the Pope[16] and a visit from the rulers of the West in homage to himself.

In 1245 Innocent had sent another mission, through another route, led by Ascelin of Lombardia, also bearing letters. The mission met with the Mongol commander Baichu near the Caspian Sea in 1247. Baichu, who had plans to capture Baghdad, welcomed the possibility of an alliance and had envoys, Aïbeg and Serkis, accompany the embassy back by to Rome, where they stayed for about a year.[17] They met with Innocent IV in 1248, who again appealed to the Mongols to stop their killing of Christians, and complained that the alliance was not moving forward.[18][19]

Saint Louis and the Mongols (1248-1254)

Louis IX of France, also called Saint Louis, had several epistolary exchanges with the Mongol rulers of the period, and organized the dispatch of ambassadors to them. Contacts started in 1248, with Mongolian envoys bearing a letter from Eljigidei, the Mongol ruler of Armenia and Persia, offering military alliance:[20] when Louis disembarked in Cyprus in preparation of his first Crusade, he was met in Nicosia with two Nestorians from Mossul named David and Marc, envoys of Eljigidei. They communicated a proposal to form an alliance with the Mongols against the Ayubids and against the Califat in Baghdad:[21]

"Whilst the King was tarrying in Cyprus, the great King of the Tartars sent messengers to him, greeting him courteously, and bearing word, amongst other things, that he was ready to help him conquer the Holy Land and deliver Jerusalem out of the hand of the Saracens. The King received them most graciously, and sent in reply messengers of his own, who remained away two years, before they returned to him. Moreover the King sent to the King of the Tartars by the messengers a tent made in the style of a chapel, which cost a great deal, for it was made wholly of good fine scarlet cloth. And to entice them if possible into our faith, the King caused pictures to be inlaid in the said chapel, portraying the annunciation of Our Lady, and all the other points of the Creed. These things he sent them by two Preaching Friars, who knew Arabic, in order to show and teach them what they ought to believe."

— "The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville", Chap. V, Jean de Joinville.[22]

In response, Louis sent André de Longjumeau, a Dominican priest, as an emissary to the Great Khan Güyük in Mongolia.[23] Unfortunately Güyük died before their arrival at his court however, and his embassy was dismissed by his widow Oghul Ghaimish, who gave them gift and a condescending letter to Saint Louis.[24]

Eljigidei planned an attack on the Muslims in Baghdad in 1248. This advance was, ideally, to be conducted in alliance with Louis, in concert with the Seventh Crusade. According to the 13th century monk and historian Guillaume de Nangis, the Mongols brought a message "from Iltchiktai" (Eljigidei), the Great Khan's lieutenant in Asia Minor, suggesting that King Louis should land in Egypt, while he attacked Bagdad, in order to prevent the Saracens of Egypt and those of Syria from joining forces.[25]

Louis IX went on to attack Egypt, starting with the capture of the port of Damietta. However, Güyük's early death, caused by drink, made Eljigidei postpone operations until after the interregnum, and the successful Siege of Baghdad would not take place until 1258.

Louis, following the loss of his army at Mansurah, looked for allies, both among the Ismailian Assassins and the Mongols.[26] In 1253, news came that Sartaq, son of Batu, had converted to Christianity,[27] and Louis dispatched an envoy to the Mongol court in the person of the Franciscan William of Rubruck, who went to visit the Great Khan Möngke in Mongolia. Möngke gave a letter to William in 1254, asking for the submission of Saint Louis.[28] In the meantime, Louis had to return to France, due to the death of his mother and regent, Blanche de Castille.

Joint conquest of Muslim Syria (1259-1260)

Full military collaboration would take place in 1259-1260 when the Franks under the ruler of Antioch Bohemond VI and his father-in-law Hetoum I allied with the Mongols under Hulagu. Hulagu was generally favourable to Christianity, and was himself the son of a Christian woman. The Mongols together with the Northern Franks of Antioch and the Armenian Christians conquered Muslim Syria, taking together the city of Aleppo, and later Damascus[29] together with the Christian Mongol general Kitbuqa:[30]

"The king of Armenia and the Prince of Antioch went to the army of the Tatars, and they all went off to take Damascus".

— Gestes des Chiprois, Le Templier de Tyr.[31]

Once a city was conquered, as in Aleppo, or as in Baghdad in 1258, the Muslims were massacred, but the Christians were spared.[32] Some of the conquered cities (including Lattakieh) were given to Bohemond VI, but the Mongols insisted that the Greek Christian patriarch Euthymius be installed in Antioch,[33] which resulted in a temporary excommunication for Bohemond.[34] The Franks of Acre also sent the Dominican David of Ashby to the court of Hulagu in 1260.[35]

Following a new conflict in Turkestan, Hulagu had to stop the invasion before it reached Egypt, and he only left about 10,000 Mongol horsemen in Syria under Kitbuqa to occupy the conquered territory:[36]

"Kitbuqa, who had been left by Hulagu in Syria and Palestine with 10,000 Tartars, held the Land in peace and in state of rest. And he greatly loved and honoured the Christians (...) Kitbuqa worked at recovering the Holy Land"

The Mamluks counter-attacked and encircled the Mongols after the Franks of Acre made a passive alliance with them and allowed their troops to go through Christian territory unhampered.[38] The Mongols were defeated at the Battle of Ain Jalut on September 3rd, 1260, and the Mamluk Baibars began to threaten Antioch, which (as a vassal of the Armenians) had supported the Mongols.[39]

On April 10th, 1262, Hulagu sent through John the Hungarian a new letter to the French king Louis IX from the city of Maragheh, offering again an alliance. The letter mentioned Hulagu's intention to capture Jerusalem for the benefit of the Pope, and asked for Louis to send a fleet against Egypt. Louis transmitted the letter to Pope Urban IV, who answered by asking for Hulagu's conversion to Christianity.[40]

In the year 1262, as the Mamluks were trying to conquer Antioch, the king of Armenia went to the Mongols and again obtained their intenvention to deliver the city.[41]

Bohemond VI was again present at the court of Hulagu in 1264, trying to obtain as much support as possible from Mongol rulers against the Mamluk progression. His presence is described by the Armemian saint Vartan:[42]

"In 1264, l'Il-Khan had me called, as well as the vartabeds Sarkis (Serge) and Krikor (Gregory), and Avak, priest of Tiflis. We arrived at the place of this powerful monarch at the beginning of the Tartar year, in July, period of the solemn assembly of the kuriltai. Here were all the Princes, Kings and Sultans submitted by the Tartars, with wonderful presents. Among them, I saw Hetoum I, king of Armenia, David, king of Georgia, the Prince of Antioch (Bohemond VI), and a quantity of Sultans from Persia.

— Vartan, trad. Dulaurier.[43]

Baibars finally took the city of Antioch in 1268, and all of northern Syria was quickly lost, leaving Bohemond with no estates except Tripoli.[44] In 1271, Baibars sent a letter to Bohemond threatening him with total annihilation and taunted him for his former alliance with the Mongols:

"Our yellow flags have repelled your red flags, and the sound of the bells has been replaced by the call: "Allâh Akbar!" (...) Warn your walls and your churches that soon our siege machinery will deal with them, your knights that soon our swords will invite themselves in their homes (...) We will see then what use will be your alliance with Abagha"

— Letter from Baibars to Bohemond VI, 1271[45]

Alliances during the Eighth and Ninth Crusades

Abagha (1234-1282), the son of Hulagu and Oroqina Khatun, a Mongol Christian, was the second Ilkhanate emperor in Persia, who reigned from 1265-1282. During his reign, Abagha, a devout Buddhist, attempted to convert the Muslims and harassing them mercilessly by promoting Nestorian and Buddhist interests ahead of the Muslims. He sent embassies to Pope Gregory X and Edward I of England. During his harsh reign, many Muslims had attempted to assassinate Abaqa. In 1265, upon his succession, he received the hand of Maria Despina Palaiologina, the illegitimate daughter of Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, in marriage.[46]

Diplomatic alliance from Pope Clement IV (1267)

The Mamluks were extending their conquests in Syria during the 1260s, putting the Syrian Franks in a difficult situation.

In 1267, Pope Clement IV and James I of Aragon sent an ambassador to the Mongol ruler Abaqa Khan in the person of Jayme Alaric de Perpignan.[47] Jayme Alaric would return to Europe in 1269 with a Mongol embassy. In a letter dated 1267, and written from Viterbo, the Pope welcomes Abagha's proposal for an alliance and informs him of a Crusade in the near future:

"The kings of France and Navarre, taking to heart the situation in the Holy Land, and decorated with the Holy Cross, are readying themselves to attacks the enemies of the Cross. You wrote to us that you wished to join your father-in-law (the Greek emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos) to assist the Latins. We abundantly praise you for this, but we cannot tell you yet, before having asked to the rulers, what road they are planning to follow. We will transmit to them your advice, so as to enlighten their deliberations, and will inform your Magnificence, through a secure message, of what will have been decided."

— 1267 letter from Pope Clement IV to Abagha[48]

On March 24th, 1267, Louis IX had indeed expressed the intention to mount a new Crusade. When he left on July 1st, 1270, however, the Eighth Crusade went to Tunis in modern Tunisia instead of Syria, for reasons which even today are not well understood. Louis IX would die of illness there, his last words being "Jerusalem".[49]

The Pope's promise was also followed by a small crusade initiated by the James I of Aragon, but ultimately handled by his two bastards Fernando Sanchez and Pedro Fernandez after a storm forced most of the fleet to return, which arrived in Acre in December 1269. At that time, Abagha had to face an invasion in Khorasan by fellow Mongols from Turkestan, and could only commit a small force on the Syrian frontier from October 1269, only capable of brandishing the threat of an invasion.[50]

When Abagha finally defeated his eastern enemies near Herat in 1270, he wrote to Louis IX offering military support as soon as the Crusaders landed in Palestine.[51]

Prince Edward and his alliance with the Mongols (1269-1274)

In 1269, the English Prince Edward (the future Edward I) started on a Crusade of his own. The number of knights and retainers that accompanied Edward on the crusade was quite small, possibly around 230 knights, other sources stating 1,000.[52] Many of the members of Edward's expedition were close friends and family including his wife Eleanor of Castile, his brother Edmund, and his first cousin Henry of Almain.

As soon as he arrived in Acre, on May 9th, 1271, he sent an embassy to the Mongol ruler of Persia Abagha, an enemy of the Muslims.[53] The embassy was led by Reginald Russel, Godefrey Welles and John Parker, and its mission was to obtain military support from the Mongols.[54].[55] In an answer dated September 4th, 1271, Abagha agreed for cooperation and asked at what date the concerted attack on the Mamluks should take place:

"The messengers that Sir Edward and the Christians had sent to the Tartars came back to Acre, and they did so well that they brought the Tartars with them"

— Eracles, p461.[56]

The arrival of the additional forces of Hugh III of Cyprus further emboldened Edward, who engaged in a raid into the Plain of Sharon, although he proved unable to take the small Mamluk fortress of Qaqun.[57] In mid-October 1271, the Mongol troops requested by Edward arrived in Syria and ravaged the land from Aleppo southward. Abagha, occupied by other conflicts in Turkestan could only send 10,000 Mongol horsemen under general Samagar from the occupation army in Seljuk Anatolia, plus auxiliary Seljukid troops,.[58] but they triggered an exodus of Muslim populations (who remembered the previous campaigns of Kithuqa) as far south as Cairo.[59] The Mongols defeated the Turcoman troops that protected Aleppo, putting to flight the Mamluk garisson in that city, and continued their advance to Maarat an-Numan and Apamea.[60]

When Baibars mounted a counter-offensive from Egypt on November 12th, the Mongols had already retreated beyond the Euphrates, unable to face the full Mamluk army.

These unsettling events however allowed Edward to negotiate a ten year peace treaty with the Mamluks. Upon hearing of the death of Henry III, Edward left the Holy Land and returned to England in 1274.

Overall, Edward's crusade gave the city of Acre a reprieve of ten years through a truce with the Mamluks.[61] However, Edward's reputation was greatly enhanced by his participation in the crusade and he was hailed by some contemporary commentators as a new Richard the Lionheart. Furthermore, some historians believe Edward was inspired by the design of the castles he saw while on crusade and incorporated similar features into the castles he built to secure portions of Wales, such as Caernarfon Castle.

New joint attempt at invading Syria (1280-1281)

Following the death of Baibars and the ensuing disorganisation of the Muslim realm, the Mongols seized the opportunity and organized a new invasion of Syrian land:

"Abaga ordered the Tartars to occupy Syria, the land and the cities, and remit them to be guarded by the Christians."

The new sultan Qalawun however managed to neutralize the threat of combined Frank-Mongol operations by signing with the Franks of Acre a 10 year truce (which he would later breach). The Mongols sent envoys to Acre to request military support, informing the Franks that they were fielding 50,000 Mongol horsemen and 50,000 Mongol infantry, but in vain.[63] However the Mongol raids were made in combination with about 200 Hospitaliers knights of the fortress of Marqab,[64][65] who considered they were not bound by the truce with the Mamluks:[66]

"In the year 1281 of the incarnation of Christ, the Tatars left their realm, crossed Aygues Froides with a very great army and invaded the land of Aleppo, Haman and La Chemele and did great damage to the Sarazins and killed many, and with them were the king of Armenia and some Frank knights of Syria."

— Le Chevalier de Tyre, Chap. 407[67]

In September 1281, 50,000 Mongol troops, together with 30,000 Armenians, Georgians, Greeks, and the Hospitalier Knights fought against Qalawun at the Second Battle of Homs, but they were repelled, with heavy loss on both sides.[68] The prior of the English Hospitallers, Joseph of Chauncy was present at the battle and sent an account to Edward I.[69]

Arghun's proposals for a new crusade (1285-1291)

The new ruler Arghun, son of Abaqa, again sent an embassy and a letter to Pope Honorius IV in 1285, a Latin translation of which is preserved in the Vatican.[70] It mentions the links to Christianity of Arghun's family, and proposes a combined military conquest of Muslim lands:[71]

"As the land of the Muslims, that is, Syria and Egypt, is placed between us and you, we will encircle and strangle ("estrengebimus") it. We will send our messengers to ask you to send an army to Egypt, so that us on one side, and you on the other, we can, with good warriors, take it over. Let us know through secure messengers when you would like this to happen. We will chase the Saracens, with the help of the Lord, the Pope, and the Great Khan."

— Extract from the 1285 letter from Arghun to Honorius IV, Vatican[72]

In the Levant, Arghon was also considered as a supporter of the Christian faith:

"This Arghon loved the Christians very much, and several times asked to the Pope and the king of France how they could together destroy all the Sarazins"

— Le Templier de Tyr [73]

Apparently left without an answer, Arghun sent another embassy to European rulers in 1287, headed by the Nestorian Rabban Bar Sauma, with the objective of contracting a military alliance to fight the Muslims in the Middle East, and take the city of Jerusalem.[74] Sauma returned in 1288 with positive letters from Pope Nicholas IV, Edward I of England, and Philip IV the Fair of France.[75]. Philip seemingly responded positively to the request of the embassy:

"And the King Philip said: if it be indeed so that the Mongols, though they are not Christians, are going to fight against the Arabs for the capture of Jerusalem, it is meet especially for us that we should fight [with them], and if our Lord willeth, go forth in full strength."

— "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China[76]

Philip also gave the embassy numerous presents, and sent one of his noblemen, Gobert de Helleville, to accompany Bar Sauma back to Mongol lands:

"And he said unto us, "I will send with you one of the great Amirs whom I have here with me to give an answer to King Arghon"; and the king gave Rabban Sawma gifts and apparel of great price."

— "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China[77]

Gobert de Helleville departed on February 2nd, 1288, with two clerics Robert de Senlis and Guillaume de Bruyères, as well as arbaletier Audin de Bourges. They joined Bar Sauma in Rome, and accompanied him to Persia.[78]

King Edward also welcomed the embassy enthusiastically:

"King Edward rejoiced greatly, and he was especially glad when Rabban Sauma talked about the matter of Jerusalem. And he said "We the kings of these cities bear upon our bodies the sign of the Cross, and we have no subject of thought except this matter. And my mind is relieved on the subject about which I have been thinking, when I hear that King Arghun thinketh as I think""

— Account of the travels of Rabban Bar Sauma, Chap. VII.[79]

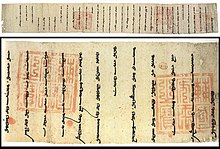

In 1289, Arghun sent a third mission to Europe, in the person of Buscarel of Gisolfe, a Genoese who had settled in Persia.[80] The objective of the mission was to determine at what date concerted Christian and Mongol efforts could start. Arghun committed to march his troops as soon as the Crusaders had disembarked at Saint-Jean-d'Acre. Buscarel was in Rome between July 15th and September 30th, 1289. He was in Paris in November-December 1289. He remitted a letter from Arghun to Philippe le Bel, answering to Philippe's own letter and promises, and fixing the date of the offensive from the winter of 1290 to spring of 1291:[81]

"Under the power of the eternal sky, the message of the great king, Arghun, to the king of France..., said: I have accepted the word that you forwarded by the messengers under Saymer Sagura (Bar Sauma), saying that if the warriors of Il Khaan invade Egypt you would support them. We would also lend our support by going there at the end of the Tiger year’s winter [1290], worshiping the sky, and settle in Damascus in the early spring [1291].

If you send your warriors as promised and conquer Egypt, worshiping the sky, then I shall give you Jerusalem. If any of our warriors arrive later than arranged, all will be futile and no one will benefit. If you care to please give me your impressions, and I would also be very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with.

I send this to you by Myckeril and say: All will be known by the power of the sky and the greatness of kings. This letter was scribed on the sixth of the early summer in the year of the Ox at Ho’ndlon."

Buscarel then went to England to bring Arghun's message to King Edward I. He arrived in London January 5th, 1290. Edward, whose answer has been preserved, answered enthusiastically to the project but remained evasive and failed to make a clear commitment.[84]

Arghun then sent a fourth mission to European courts in 1290, led by a certain Andrew Zagan, who was accompanied by Buscarel of Gisolfe and a Christian named Sahadin.[85]

All these attempts to mount a combined offensive failed. On March 1291, Saint-Jean-d'Acre was conquered by the Mamluks in the Siege of Acre. Arghun himself died on March 10th, 1291, putting an end to his efforts towards combined action.[86]

Had the alliance succeeded, the existence of the Christian kingdoms in the Middle-East would probably have been prolonged, the Mamluks would have been destroyed, and the Mongol Il-Khanate would probably have prospered as an ally of the Christians in the Holy Land.[87]

Joint operation in the Levant (1298-1303)

From around 1298, the Knights Templar and their leader Jacques de Molay strongly advocated, and entered into, a collaboration with the Mongols and fought against the Mamluks.[88] The plan was to coordinate actions between the Christian military orders, the King of Cyprus, the aristocracy of Cyprus and Little Armenia and the Mongols of the khanate of Ilkhan (Persia). Following his return to Cyprus in 1296, Jacques Molay campaigned on the coasts of Egypt.[89] In 1298 or 1299, Jacques de Molay campaigned in Armenia,[90] but around that time, the fortress of Roche-Guillaume in the Belen pass, the last Templar stronghold in Antioch, was lost to the Mamluks.[citation needed]

The Mongol khan of Persia, Ghâzân, allied with the Armenians, defeated the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in December 1299. Henry II of Jerusalem, king of Cyprus, allied with Ghazan and sent 15 frigates to Egypt to support the offensive.[91] Damascus fell on January 1300 and admitted Mongol suzerainty.[92][93]

James II of Aragon, sent a congratulation letter to Ghazan for his victories.[94] Ghazan however soon had to leave with his troops because another conflict erupted in Central Asia with the Chagatai Khanate.

Numerous stories circulated in the West that in 1299-1300 Jacques de Molay, in alliance with the Mongols, managed to capture Jerusalem for a brief period.[95] Various historians described this event,[96], and even painted it (Versailles painting by Claude Jacquand), but it is thought that it never actually happened.[97]

In 1300, Jacques de Molay made his order commit raids along the Egyptian and Syrian coasts to weaken the enemy's supply lines as well as to harass them, and in November that year he joined the occupation of the tiny fortress island of Ruad (today called Arwad) which faced the Syrian town of Tortosa. The intent was to establish a bridgehead in accordance with the Mongol alliance.[98] Ghazan sent an envoy to inform that he would join the Franks during the winter, but adversed conditions stopped him from coming:

"That year [1300], a message came to Cyprus from Ghazan, king of the Tatars, saying that he would come during the winter, and that he wished that the Frank join him in Armenia (...) Amalric of Lusignan, Constable of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, arrived in November (...) and brought with him 300 knights, and as many or more of the Templars and Hospitallers (...) In February a great admiral of the Tatars, named Cotlesser, came to Antioch with 60,000 horsemen, and requested the visit of the king of Armenia, who came with Guy of Ibelin, Count of Jaffa, and John, lord of Giblet. And when they arrived, Cotelesse told them that Ghazan had met great trouble of wind and cold on his way. Cotlesse raided the land from Haleppo to La Chemelle, and returned to his country without doing more".

— Le Templier de Tyre, Chap 620-622[99]

In 1301 Ghazan sent an embassy to the Pope, and in 1303 to Edward I, in the person of Buscarello de Ghizolfi, reinterating Hulagu's promise that they would give Jerusalem to the Franks in exchange for help against the Mamluks.[100]

In September 1302 the Templars were driven out of Ruad by the attacking Mamluk forces from Egypt, and many were massacred when trapped on the island. The island of Ruad was lost, and Molay returned to Chypre with the remainder of the Order in 1303. They made a raid on Tortose in 1303.[101] Ghâzân was defeated in 1303 at the Battle of Shaqhab, and died in 1304: dreams of a rapid reconquest of the Holy Land were destroyed.

Oljeitu and the failed Crusade project (1305-1313)

Oljeitu, also named Mohammad Khodabandeh, was the great-grandson of the Ilkhanate founder Hulagu, and brother and successor of Mahmud Ghazan. His Christian mother baptized him as a Christian and gave him the name Nicholas [citation needed]. In his youth he at first converted to Buddhism and then to Sunni Islam together with his brother Ghazan. He then changed his first name to the Islamic name Muhammad. In April 1305, Oljeitu sent letters the French king Philip the Fair,[102] the Pope, and Edward I of England. After his predecessor Arghun, he offered a military collaboration between the Christian nations of Europe and the Mongols against the Mamluks. He also explained that internal conflicts between the Mongols were over:

"Now all of us, Timur Khagan, Tchapar, Toctoga, Togba and ourselves, main descendants of Gengis-Khan, all of us, descendants and brothers, are reconciled through the inspiration and the help of God. So that, from Nangkiyan (China) in the Orient, to Lake Dala our people is united and the roads are open."

— Extract from the letter of Oljeitu to Philip the Fair. French national archives.[103]

European nations accordingly prepared a crusade, but were delayed. In the meantime Oljeitu launched a last campaign against the Mamluks (1312-13), in which he was unsuccessful. A settlement with the Mamluks would only be found when Oljeitu's son signed the Treaty of Aleppo with the Mamluks in 1322.[104]

Last contacts (1322)

In 1320, the Egyptian sultan Naser Mohammed ibn Kelaoun invaded and ravaged Christian Armenian Cilicia. In a letter dated July 1st, 1322, Pope John XXII sent a letter from Avignon to the Mongol ruler Abu Sa'id, reminding him of the alliance of his ancestors with Christians, asking him to intervene in Cilicia. At the same time he advocated that he abandon Islam in favor of Christianity. Mongol troops were sent to Cilicia, but only arrived after a ceasefire had been negotiated for 15 years between Constantin, patriarch of the Armenians, and the sultan of Egypt. After Abu Sa'id, relations between Christian princes and the Mongols were totally abandoned.[105]

He died without heir and successor. The state lost its status after his death, becoming a plethora of little kingdoms run by Mongols, Turks, and Persians.

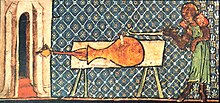

Technology exchanges

In these invasions westward, the Mongols brought with them a variety of eastern, often Chinese technologies, which may have been transmitted to the West on these occasions. The original weaknesses of the Mongols in siege warfare (they were essentially a nation of horsemen) were compensated by the introduction of Chinese engineering corps within their army,[106] who therefore had ample contacts with Western lands.

One theory of how gunpowder came to Europe is that it made its way along the Silk Road through the Middle East; another is that it was brought to Europe during the Mongol invasion in the first half of the 13th century.[107][108] Direct Franco-Mongol contacts occurred as in the 1259-1260 military alliance of the Franks knights of the ruler of Antioch Bohemond VI and his father-in-law Hetoum I with the Mongols under Hulagu.[109] William of Rubruck, an ambassador to the Mongols in 1254-1255, a personal friend of Roger Bacon, is also often designated as a possible intermediary in the transmission of gunpowder know-how between the East and the West.[110]

Other innovations, such as printing, may have transited through the Mongol routes during that period. Pierre de Montaigu, Master of the Knights Templar from 1219 to 1223, is said to have brought the compass from a meeting with the Mongols in Damas.[111]

Notes

- ^ Between the 11th to the 15th century, the Crusaders were usually called Franks. The term led to derived usage by other cultures, such as Farangi, firang, farang and barang.

- ^ Foltz "Religions of the Silk Road"

- ^ Source

- ^ Runciman, p.246

- ^ Grousset, p.698

- ^ Runciman, p.246

- ^ Runciman, p.246

- ^ Runciman, p.246-247

- ^ Regesta Honorii Papae III, no 1478, I, p.565. Quoted in Munciman, p.246

- ^ Runciman, p.249

- ^ Runciman, p.250

- ^ Runciman, p.253

- ^ Runciman, p.256

- ^ Runciman, p.254

- ^ Sharan Newman, "Real History Behind the Templars" p. 174, about Grand Master Thomas Berard: "Under Genghis Khan, they [the Mongols] had already conquered much of China and were now moving into the ancient Persian Empire. Tales of their cruelty flew like crows through the towns in their path. However, since they were considered "pagans" there was hope among the leaders of the Church that they could be brought into the Christian community and would join forces to liberate Jerusalem again. Franciscan missionaries were sent east as the Mongols drew near."

- ^ David Wilkinson, Studying the History of Intercivilizational Dialogues [1]

- ^ Muncinis, p.259

- ^ David Wilkinson, Studying the History of Intercivilizational Dialogues [2]

- ^ Muncinis, p.259

- ^ The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260 Peter Jackson The English Historical Review, Vol. 95, No. 376 (Jul., 1980), pp. 481-513 [3]

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades", Rene Grousset, p.523, ISBN 226202569X

- ^ The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville

- ^ Runciman, p.260

- ^ Runciman, p.260

- ^ "The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville", Chap. V, Jean de Joinville.The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville

- ^ Runciman, p279-280

- ^ Runciman, p.380

- ^ J. Richard, 1970, p. 202., Encyclopedia Iranica, [4]

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades", René Grousset, p581, ISBN 226202569X

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p581

- ^ "Le roy d'Arménie et le Prince d'Antioche alèrent en l'ost des Tatars et furent à prendre Damas". Quoted in "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p586

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.306

- ^ Runciman, p.306

- ^ Online Reference Book for Medieval studies

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica article

- ^ Runciman, p.310

- ^ Quoted in "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p593

- ^ Runciman, p.312

- ^ Runciman, p.313

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica article

- ^ "In the year 1262, the sultan Bendocdar of Babiloine, who had taken the name of Melec el Vaher, put the city of Antioch under siege, but the king of Armenia went to see the Tatars and had them come, so that the Sarazins had to leave the siege and return to Babiloine.". Original French:"Et en lan de lincarnasion .mcc. et .lxii. le soudan de Babiloine Bendocdar quy se fist nomer Melec el Vaher ala aseger Antioche mais le roy dermenie si estoit ale a Tatars et les fist ehmeuer de venir et les Sarazins laiserent le siege dantioche et sen tornerent en Babiloine."Source #316

- ^ "Grousset, p565

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.565

- ^ Runciman, 325-327

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.650

- ^ Runciman, p.320

- ^ Runciman, p330-331

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.644

- ^ Grousset, p.647

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.332

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.332

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.656

- ^ "He knew that his own army was small, but he hoped to unite the Christians of the East into a formidable body and then to use the help of the Mongols in making an effective attack on Baibars", in "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.335

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.653. Grousset quote a contemporary source ("Eracles", p.461) explaining that Edward contacted the Mongols "por querre secors" ("To ask for help")

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.336

- ^ Quoted in "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.653.

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.337

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.336

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.653.

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.336

- ^ Runciman, p.337

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.689

- ^ Grousset, p.687

- ^ Grousset, p.687

- ^ "The Crusades Through Arab Eyes", p. 253: The fortress of Marqab was held by the Knights Hospitallers, called al-osbitar by the Arabs, "These monk-knigts had supported the Mongols wholeheartedly, going so far as to fight alongside them during a fresh attempted invasion in 1281."

- ^ Runciman, p.391

- ^ Original French:"En lan de .m. et .cc. et .lxxxi. de lincarnasion de Crist les Tatars nyssirent de lor terres et passerent les Aygues Froides a mout grant host et coururent la terre de Halape et de Haman et de La Chemele et la saresterent et firent grant damage as Sarazins et en tuerent ases et fu le roy dermenie aveuc yaus et aucuns chevaliers frans de Surie." Source. Nota: "Aucuns" means "several", "some" in 13th century French Source, and is always used with this meaning in Le Chevalier de Tyre.

- ^ Runciman, p.392

- ^ Runciman, p.391

- ^ Runciman, p.398

- ^ "The Crusades Through Arab Eyes" p. 254: Arghun, grandon of Hulegu, "had resurrected the most cherished dream of his predecessors: to form an alliance with the Occidentals and thus to trap the Mamluk sultanate in a pincer movement. Regular contacts were established between Tabriz and Rome with a view to organizing a joint expedition, or at least a concerted one."

- ^ Quote in "Histoires des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p700

- ^ French original:"Cestu Argon ama mout les crestiens et plusors fois manda au pape et au roy de France trayter coment yaus et luy puissent de tout les Sarazins destruire" Source #591

- ^ Runciman, p.398

- ^ Boyle, in Camb. Hist. Iran V, pp. 370-71; Budge, pp. 165-97. Source

- ^ http://www.aina.org/books/mokk/mokk.htm

- ^ http://www.aina.org/books/mokk/mokk.htm

- ^ "Histoires des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, quoting "La Flor des Estoires d'Orient" by Haiton

- ^ "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge Source

- ^ Runciman, p.401

- ^ Runciman, p.401

- ^ Source

- ^ For another translation here

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset.

- ^ Runciman, p.402

- ^ Runciman, p.412

- ^ "Had the Mongol alliance been achieved and honestly implemented by the West, the existence of Outremer would almost certainly have been prolonged. The Mamluks would have been crippled if not destroyed; and the Ilknate of Persia would have survived as a power friendly to the Christians and the West". Runciman, p.402

- ^ "L’ordre du Temple et son dernier grand maître, Jacques de Molay, ont été les artisans de l’alliance avec les Mongols de Perse contre les Mamelouks en 1299-1303, afin de reprendre pied en Terre sainte." Alain Demurger, Master of Conference at Université Paris-I, author of « Chevaliers du Christ. Les ordres religieux militaires au Moyen Age » (Seuil, 2002), « Jacques de Molay. Le crépuscule des Templiers » (Payot, 2002) « Les Templiers. Une chevalerie chrétienne au Moyen Age » (Seuil), in an interview with Le Point Source

- ^ "Real History Behind the Templars" p. 231 (about Grand Master Jacques de Molay): "Jacques returned to Cyprus in late 1296 and stayed in the East for the next ten years. He conducted naval raids on Egypt and participated in another ill-fated expedition to Armenia around 1299, in which the last Templar holding in that kingdom was lost".

- ^ Newman, p. 231, that says that De Molay had an "ill-fated expedition to Armenia around 1299, in which the last Templar holding in that kingdom was lost."

- ^ According to the "Chronicle of Cyprus", by FLorio Bustron, quoted in in "Adh-Dhababi's Record of the Destruction of Damascus by the Mongols in 1299-1301", Note 18, p.359

- ^ Runciman, p.439

- ^ "Adh-Dhababi's Record of the Destruction of Damascus by the Mongols in 1299-1301"

- ^ "Adh-Dhababi's Record of the Destruction of Damascus by the Mongols in 1299-1301", Note 18, p.359

- ^ "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event" Sylvia Schein, The English Historical Review, Vol. 94, No. 373 (Oct., 1979), p. 805, Source

- ^ "Le grand-maître s'etait trouvé avec ses chevaliers en 1299 à la reprise de Jerusalem", François Raynouard, Précis sur les Templiers, 1805 online

- ^ "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event" Sylvia Schein, The English Historical Review, Vol. 94, No. 373 (Oct., 1979), p. 805, Source

- ^ "The Trial of the Templars", Malcolm Barber, 2nd edition, page 22: "In November, 1300, James of Molay and the king's brother, Amaury of Lusignan, attempted to occupy the former Templar stronghold of Tortosa. A force of 600 men, of which the Templars supplied about 150, failed to establish itself in the town itself, although they were able to leave a garrison of 120 men on the island of Ruad, just off the coast. The aim was to link up with Ghazan, the Mongol Il-Khan of Persia, who had invited the Cypriots to participate in joint operations against the Mamluks, but it does appear that this was intended as a step in a more long-term project in that, in November 1301, Boniface VIII granted the island to the Order. The plan failed for, following a very severe winter, in mid-1302, the Mamluks forced the defenders to surrender, enslaving the Templars and beheading the Syrian footsoldiers. Nearly 40 of these men were still in prison in Cairo years later where, according to a former fellow prisoner, the Genoese Matthew Zaccaria, they died of starvation, having refused an offer of 'many riches and goods' in return for apostasising".

- ^ Source

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica article

- ^ Les Croisades. Hervé Husson et Fabian Müllers, Centre de Développement en Art et Culture Médiévale, Source

- ^ Mostaert and Cleaves, pp. 56-57, Source

- ^ Source

- ^ Mostaert and Cleaves, pp. 56-57, Source

- ^ Source

- ^ "Atlas des Croisades", p.112

- ^ Norris 2003:11

- ^ Chase 2003:58

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades", René Grousset, p581, ISBN 226202569X

- ^ "The Eastern Origins of Western Civilization", John M.Hobson, p186, ISBN 0521547245

- ^ Source

References

- "Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291", Rene Grousset, editions Perrin, ISBN 226202569

- "Atlas des Croisades", Jonathan Riley-Smith, Editions Autrement, ISBN 2862605530

- Encyclopedia Iranica, Article on Franco-Persian relations

- "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. Online

- "The history and Life of Rabban Bar Sauma", translated from the Syriac by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge Online

- "Religions of the Silk Road : overland trade and cultural exchange from antiquity to the fifteenth century", Foltz, Richard (2000). New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-23338-8.

- "A history of the Crusades 3", Steven Runciman, Penguin Books, ISBN 9780140137057

- "Adh-Dhababi's Record of the Destruction of Damascus by the Mongols in 1299-1301" Translated by Joseph Somogyi. From: Ignace Goldziher Memorial Volume, Part 1, Online

- Sharan Newman, "Real History Behind the Templars"

- Maalouf, Amin. "The Crusades Through Arab Eyes", New York: Schocken Books, 1984. ISBN 0-8052-0898-4

- Barber, Malcom, "The Trial of the Templars", 2nd edition, (Cambridge, 1978)

- Sharan Newman, "Real History Behind the Templars"