Bilstein Office

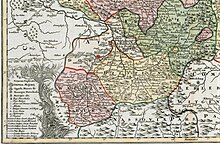

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 51 ° 6 ' N , 8 ° 1' E |

|

| Basic data (as of 1969) | ||

| Existing period: | 1434-1969 | |

| State : | North Rhine-Westphalia | |

| Circle : | District of Olpe | |

| Residents: | ||

| Office structure: | 4 municipalities | |

The Bilstein office was first mentioned in a document in 1434 with Johan van dem Broike as bailiff. Its history is closely linked to the Fredeburg office . It belonged to the Duchy of Westphalia from 1445 to 1803 and thus to the Electorate of Cologne until its dissolution . After a few years of belonging to the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt (from 1806 Grand Duchy of Hesse ) it fell to Prussia on August 1, 1816, after the Congress of Vienna, together with the rest of the Duchy. There it formed part of the newly established administrative district of Arnsberg with interruptions between 1817 and 1841 until its final dissolution in 1969 .

Origin of the office

The origin of the office can be traced back to the time of the rule of Bilstein-Fredeburg. In 1366, Count Engelbert III. von der Mark after the death of the last nobleman of Bilstein, Johann II, who took over his rule. Soon afterwards, the first signs of office formation can be identified. In 1444 and 1445, the Archbishop of Cologne, Dietrich von Moers, conquered the rule of Bilstein-Fredeburg during the so-called Soest feud and incorporated the area into the official organization of the Duchy of Westphalia.

Electoral Cologne time

In the Electoral Cologne era, the Droste represented the sovereign in government duties. The function is roughly with the bailiff , Amtshauptmann , district president or district comparable. Up to 1555 there was a frequent change of office. This is also due to the fact that the electors obtained new sources of money (e.g. to finance wars) by pledging their offices. As Drosten with a term of office of more than 10 years and more are named: Johann von Hatzfeld, Herr zu Wildenburg (1454 to 1478) and Bertram von Nesselrode (1520 to 1530). At the beginning of 1556, the Drostenamt fell to Friedrich von Fürstenberg and stayed with the Fürstenberg house (Waterlappe-Herdringen line) until 1802:

- 1556–1567 Friedrich von Fürstenberg

- 1567–1618 Kaspar von Fürstenberg

- 1618–1646 Friedrich von Fürstenberg

- 1646–1662 Friedrich von Fürstenberg

- 1662–1682 Johann Adolf von Fürstenberg

- 1682–1718 Ferdinand von Fürstenberg

- 1718–1755 Christian Franz Theodor von Fürstenberg

- 1755–1791 Clemens Lothar Ferdinand von Fürstenberg

- 1792–1802 Friedrich Leopold von Fürstenberg

The magic trials of the court in the Bilstein office

During the tenure of Drosten Friedrich von Fürstenberg (1618–1646) what from today's point of view were terrible events of the witch hunt or witch trials. Based on the more recent investigations by archivist Martin Vormberg, it seems appropriate to speak of magic trials instead of witch trials, since not only women ( witches ) but also men were persecuted to a greater extent and this term is also used in the legal basis for the proceedings is used.

The reason for the persecutions was the idea that prevailed in all strata of the population that one could influence people with the help of magic . A distinction was made between white magic , which was considered useful for people, and the black magic that was condemned , the so-called harmful magic . This mindset was supported u. a. through the uncertainty of faith in the Reformation , the turmoil in the Thirty Years War and epidemics like the plague .

People whose ancestors or relatives had previously been accused of sorcery were particularly suspected. As if in a kind of clan liability, the accusations of magic were carried over to subsequent generations. In the local community, these people were branded. The trials from around 1600 had an after-effect on what happened around 1629/30

The legal basis for the witchcraft or sorcery trials was the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (translated: Embarrassing neck court order of Emperor Charles V ). This Constitutio, which provided for interrogation under torture and also the death penalty for certain offenses of magic, formed the framework for the Electoral Cologne Witch Trial Code issued on June 24, 1607 by Ferdinand von Bayern (Coadjutor of the Electorate of Cologne). It served as a guide for the judges and included: a. a list of facts that could be used to justify torture (e.g. a person suspected of sorcery was seen in a stable where cattle became sick). As a serious deficiency of the witch trial code, von Vormberg pointed out that the accused was not given the opportunity to be defended by a legal scholar and that judgments were not reviewed by a higher authority.

For the area of the Bilstein office, the trials of 1629 and 1930 are the second wave, after a total of 80 indictments between 1590 and 1603. A total of 275 people (almost half of them men) were charged with the suspicion of sorcery in the Bilstein office in 1629/30, that is 8.5 percent of the estimated 3,200 inhabitants of the affected places. Of these, 59 were charged (more than half of them men). The defendants, for their part, tortured 469 men and women (around 12 percent of the population) who they allegedly saw performing the devil dance on the Witches' Sabbath . A total of 32 of the 59 accused were sentenced to death and executed. The remaining process logs were all evaluated in accordance with the investigation mentioned above. With regard to the testimony and a. in relation to origin, status and age of the witnesses, statements from hearsay and statements from their own knowledge and experience. Regarding the interrogation of the accused were the statements to allegations as sex with the Devil , black magic , animal transformations ( werewolf ) u. a. analyzed.

Apart from the absurd allegations, Vormberg's investigations show that the procedures also had massive shortcomings. Accusations of magic based solely on hearsay and rumors led to unchecked convictions. Confessions of guilt were often extorted through torture; the possibility of appeals and review of judgments by a higher authority did not exist according to the mentioned witch trial code. It is interesting to note that not only women were accused, as the term witch hunt suggests, but men were also tried. A focus on persecution of certain professional groups (e.g. midwives) could not be verified. A special influence of church circles on the processes could not be proven either. The reasons for a rapid decrease in the magic processes in the Bilstein office after 1629/30 could not be deduced from the minutes. However, a rethinking process may have started among the sovereign and in science.

Hessian and Prussian times

When the Duchy of Westphalia was redistributed into 18 offices in 1807, the Bilstein office remained in place, but was reduced to include the Helden parish. The bailiff was Ferdinand Freusberg. It now included the parishes of Elspe , Förde , Heinsberg , Kirchhundem , Kirchveischede , Kohlhagen , Lenne , Oberhundem , Saalhausen and Rahrbach . Shortly after the duchy passed to Prussia, the district of Bilstein was founded in 1817 with its seat in Bilstein . The competence of the old Bilstein office was limited to the administration of justice. But a little later, in 1819, the district was renamed District Olpe and Olpe became the new district town. From this Heinsberg, Kirchhundem, Kohlhagen, Lenne, Oberhundem and Saalhausen were spun off into the Kirchhundem office in 1830 . The Bilstein office was re-established as an administrative unit in 1841. The municipalities of Bilstein, Elspe, Förde and Rahrbach belonged to the office. The seat of this office was initially the private house of the first bailiff below Bilstein Castle . The headquarters remained in Bilstein until 1939, when the administration moved to Grevenbrück in May .

Head of administration 1841–1969

| Term of office | Head of administration | Official title |

|---|---|---|

| 1841-1881 | Joseph Hartmann | Bailiff |

| 1881-1886 | Ernst Liebau | Bailiff |

| 1886-1923 | Franz Anton Schulte | Bailiff |

| 1923-1933 | Karl Graefenstein | bailiff until 1927, mayor from 1927 |

| 1933 | Eugen Schaub | Mayor until 1935, mayor from 1935 |

| 1945-1947 | Franz Keseberg | Office Director |

| 1947-1969 | Rudolf Rettig | Office Director |

coat of arms

The (last) coat of arms of the Bilstein office was based on a design by the heraldist Waldemar Mallek on November 22nd, 1937 with the dedication “A black cross on a silver shield with 4 red stars and a heart shield with 3 green posts in a golden field occupied is “awarded. The cross was taken from the coat of arms of Kurköln , the four stars stand for the four municipalities of the office.

City of Lennestadt

As part of the municipal reorganization in the Sauerland (see Olpe Law ), the Bilstein office was dissolved on June 30, 1969. In this area, the city of Lennestadt was re-established as the legal successor on July 1, 1969 . In the period from 1969 to 1984, additional rooms in other buildings in Grevenbrück and Altenhundem were rented for the administration in order to cope with the higher number of administrative acts. During this time there were long discussions about the location of a central town hall. Altenhundem was finally able to prevail on the question of the administrative headquarters. Lennestadt's town hall has been located here since 1984. The Lennestadt City Museum with library and city archive is now located in the former Grevenbrück administrative building .

literature

- Günter Becker and Hans Mieles: Bilstein - Land, Burg und Ort - Contributions to the history of the Lennestadt area and the former rule of Bilstein , compiled by Günther Becker, Lennestadt, 1975 on behalf of the city of Lennestadt.

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm Janssen: Marshal Office Westphalia - Office Waldenburg - County Arnsberg - Dominion Bilstein-Fredeburg: The emergence of the territory "Duchy of Westphalia", in: Harm Klueting / Jens Foken (ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia, Volume 1. The Electorate of Cologne Duchy of Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne's rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803, Münster 2009, pp. 258–260.

- ↑ s. also Hans Mieles, Bilstein under the rule of Kurköln, in: Günther Becker and Hans Mieles, Bilstein - Land Burg und Ort -, contributions to the history of the Lennestadt area and the former rule of Bilstein, Lennestadt 1975, pp. 71-75

- ↑ cf. Martin Vormberg, Die Zaubereiprozesse des Kurkölnischen Court Bilstein 1629 - 1630, series of publications of the district of Olpe No. 38, Olpe, p. 165

- ↑ cf. Martin Vormberg, The Magic Trials of the Electoral Cologne Court Bilstein 1629 - 1630, pp. 80,85

- ↑ see: Martin Vormberg, Die Zaubereiprozesse des Kurkölnischengericht Bilstein 1629 - 1630, p. 23

- ↑ cf. Martin Vormberg, The Magic Trials of the Electoral Cologne Court Bilstein 1629 - 1630, p. 187

- ↑ cf. Martin Vormberg, Die Zaubereiprozesse des Kurkölnischen Court Bilstein 1629 - 1630, pp. 185–188

- ↑ Manfred Schöne: The Duchy of Westphalia under Hesse-Darmstadt rule 1802-1816, Olpe 1966, pp. 42f and 17.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Behr: State and Politics in the 19th Century, in: Harm Klueting / Jens Foken: Das Herzogtum Westfalen Volume 2. The former Electoral Cologne Duchy of Westphalia in the area of today's Hochsauerland, Olpe Soest and Märkischer Kreis (19th and 20th centuries) Century), Münster 2012, p. 33.

- ↑ Behr p. 37.

- ↑ Dieter Tröps: The Prussians came in 1816, but the administration remains in Bilstein . In: Stadt Lennestadt (Ed.): The long way to the Lennestädter Rathaus , 1984, pp. 7-17.