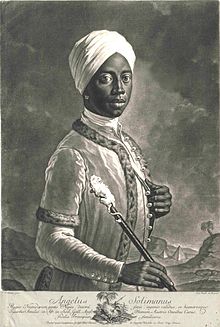

Angelo Soliman

Angelo Soliman (* around 1721, presumably in what is now northeastern Nigeria ; † November 21, 1796 in Vienna ) was an Afro-Austrian valet , prince tutor to Hereditary Prince Alois I of Liechtenstein and a Freemason . He achieved fame in 18th century Vienna during his lifetime.

Life

Angelo Soliman probably came from the Kanuri people in the northeast of today's Nigeria , according to his own account he belonged to the chief line of the tribe of the Magumi Kanuri . After the destruction of his tribe through armed conflicts, he fell into the hands of the victors, who exchanged him for a horse to Europeans. He was herding camels in a colony in Africa. Here he was given the name André . At the age of ten he was taken by ship to Messina , where he had been bought as a present for a marquise. She took care of his education. He took the name Angelo out of affection for a servant named Angelina . The surname Soliman was added. He was baptized on September 11th. He celebrated that day later than his birthday. After several requests, it was given to Prince Johann Georg Christian von Lobkowitz around 1734 , who appointed him as valet, soldier and travel companion. Soliman saved his life in a battle, which makes his later social position understandable. After Lobkowitz's death, Soliman came to Prince Wenzel von Liechtenstein in 1753 , where he was promoted to head of the servants. Emperor Josef II valued Soliman as a partner, Franz Moritz Graf von Lacy was friends with him.

Without the prince's knowledge, Soliman married Magdalena, née von Kellermann, widowed Christiani, on February 6, 1768. Liechtenstein had forbidden marriages of his servants in order to avoid later burdens on his court to provide for the bereaved. However, through an indiscretion by Joseph II , he found out about the marriage and released Soliman without notice.

Soliman's daughter Josephine († 1801 in Cracow) was born on December 18, 1772. In 1797 she married the military engineer at the time, Ernst Freiherr von Feuchtersleben. Her son Eduard von Feuchtersleben , born in 1798, later studied mining science and became master brewer in Bad Aussee . He wrote travelogues in the romantic spirit when he was younger.

In 1773 the new prince, Franz Josef von Liechtenstein , hired Soliman again as prince tutor. This was supposed to make up for Soliman's dismissal by his predecessor and uncle.

In 1781 Soliman was accepted into the Freemason lodge Zur True Eintracht in Vienna. Soliman was friends with the mineralogist , writer and Freemason Ignaz von Born , who joined the same lodge on Soliman's recommendation. When von Born became master of the chair shortly afterwards , Soliman first took over the office of preparatory brother, later that of vice master of ceremonies . From this group, Soliman cultivated a friendship with the Hungarian national poet Ferenc Kazinczy (1759–1831) since 1786 .

Dealing with Soliman's corpse

After his death from a stroke in 1796, the sculptor Franz Thaler made a death mask from Soliman's head. His internal organs were buried , his skin was dissected and exhibited until 1806 in the Imperial Natural History Cabinet as a half-naked savage with feathers and a shell chain. It is highly controversial whether Soliman was induced by friends to “make his skin available to the public” and whether his wish “that he would be remembered later” played a role in his alleged decision to donate his skin and leave it for preparation (pro: Monika Firla, Victoria E. Moritz; contra: Walter Sauer, Erich Sommerauer, Iris Wigger, Katrin Klein). His daughter, Baroness Josephine von Feuchtersleben, protested against the exhibition of her dead father as a curiosity and tried in vain to have the body parts returned and Christian burial.

The presentation of the prepared body is presented in different ways: On the one hand, it is claimed that Soliman's prepared body parts, dressed in loincloth, feather crown and shell necklaces, stood in front of an African backdrop with three other stuffed Africans, surrounded by exotic animal specimens. On the other hand, it is alleged that Soliman's prepared body, depicted as a wild man, was kept in a glass cabinet behind a curtain, but was not exhibited, although the exhibition also included a prepared African.

Philipp Blom suspects that the preparation was done directly at the instigation of the emperor, since Soliman embodied the enlightening Vienna he hated. “The stuffing probably had a waddling effect on the enlightened circles who welcomed him with open arms during his lifetime. This act of making a person an object again, and this time a decidedly racist, colonialist act, seems to be embodied symbolically. It's more than just scientific curiosity, and that's what makes this act so monstrous. That is also a posthumous insult. "

Nothing is known about the whereabouts of the body, skeleton and skull after the preparation of the skin.

During the Vienna October Uprising in 1848 , Soliman's mummified body was burned . Soliman's plaster bust is now in the Rollett Museum in Baden near Vienna in the permanent exhibition there.

Honors

In 2013, in Vienna- Landstrasse (3rd district ), a partially covered foot / bike passage to the Danube Canal at the northern end of Löwengasse , Angelo-Soliman-Weg , was named after him after the application to rename Löwengasse had been rejected.

Soliman was also the motif of a 55-cent postage stamp from 2006. With a lion-crowned scepter in hand, he looks proudly at the viewer, with Austria written underneath . "This is a somewhat questionable, if not self-deprecating, integration into the Australian heritage," commented Paul Jandl .

reception

literature

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Angelo, Soliman . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 22nd part. Imperial-Royal Court and State Printing Office, Vienna 1870, p. 464 ( digital copy ).

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Soliman, Angelo . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 35th part. Kaiserlich-Königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1877, pp. 248–251 ( digitized version ).

- Wilhelm A. Bauer: Angelo Soliman, the high princely Moor. An exotic chapter of old Vienna . Edited and introduced by Monika Firla-Forkl. Edition Ost, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-929161-04-4 .

- Monika Firla: Angelo Soliman in Viennese society from the 18th to the 20th century, in foreign experiences. Asians and Africans in Germany, Austria and Switzerland until 1945. Edited by Gerhard Höpp . Das Arabische Buch, Berlin 1996 ISBN 3-86093-111-3 , pp. 69-96

- Monika Firla: Does Soliman embody us? Or: did he donate his skin himself? A provocation for "Station * Corpus" . Vienna 2001

- Monika Firla: "Blessings, blessings, blessings on you, good man!" Angelo Soliman and his friends Count Franz Moritz von Lacy, Ignaz von Born, Johann Anton Mertens and Ferenc Kazinczy. 2nd edition, Tanz-Hotel / Art-Act Kunstverein, Vienna 2003 DNB 977749924 .

- Monika Firla: Angelo Soliman. A Viennese African in the 18th century (catalog for the exhibition March 11 to August 2, 2004). Rollettmuseum, Baden Lower Austria 2004, ISBN 3-901951-48-2 .

- Monika Firla: Angelo Soliman's exhibit, Joseph Carl Rosenbaum as his unknown observer and the question of the public . Stuttgart 2012

- Walter Sauer : Angelo Soliman. Myth and Reality . In: ders. (Ed.): From Soliman to Omafumo. African diaspora in Austria - 17th to 20th centuries . StudienVerlag, Innsbruck 2007, pp. 59–96, ISBN 978-3-7065-4057-5 .

- Walter Sauer: From memory to myth. Angelo Soliman and the projections of posterity . In: Philip Blom, Wolfgang Kos (ed.): Angelo Soliman. An African in Vienna. Brandstätter, Vienna 2011, pp. 133-143, ISBN 978-3-85033-594-2 .

- Iris Wigger, Katrin Klein: ›Brother Mohr‹. Angelo Soliman and the Racism of the Enlightenment . In: Wulf D. Hund (Ed.): Alienated bodies. Racism as desecration of a corpse . Transcript, Bielefeld 2009, ISBN 978-3-8376-1151-9 , pp. 81-115.

- Philipp Blom, Wolfgang Kos (Ed.): Angelo Soliman. An African in Vienna. Brandstätter, Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-85033-594-2 .

- Gergely Péterfy : The stuffed barbarian . Novel. Translated from the Hungarian by György Buda. [Orig .: Kitömött barbár , Pozsony 2014]. Nischen Verlag, Vienna 2016. ISBN 978-3-9503906-2-9 .

- Felix Mitterer : None of you , Roman, Haymon Verlag, Innsbruck 2020, 978-3-7099-3495-1.

Movie

- Markus Schleinzer, Alexander Brom: Angelo (historical film) . 2018.

Web links

- Literature by and about Angelo Soliman in the catalog of the German National Library

- Vienna History Wiki

- Monika Firla: Does Soliman embody us? Or: did he donate his skin himself? A provocation to STATION * CORPUS . Vienna 2001

- Angelo Soliman and his friends in the nobility and in the intellectual elite . Federal Agency for Civic Education

- Angelo Soliman . SADOCC - Southern Africa Documentation and Cooperation Center

- Heiner Wember: Angelo Soliman, "Wiener Hofmohr" (funeral day 23.11.1796) WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

- From child slaves to the stuffed “Hofmohr” of Vienna . In: Der Standard , September 28, 2011, accessed May 2, 2013

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Hans Bankl , Columbus not only brought the tomatoes: Stories behind the story (2004), ISBN 3-442-15292-5 ( digitized version )

- ↑ bpb.de

- ↑ Exotic lackeys for Europe's aristocratic palaces . SPIEGEL Online, excerpt from: Michaela Vieser : Von Kaffeerieücher, Settlers and Fischbeinreissern , C. Bertelsmann Verlag, ISBN 978-3570100585 . Retrieved on 2013-17-06.

- ↑ Monika Firla: Angelo Soliman and his friends in the nobility and in the intellectual elite - bpb. In: bpb.de. July 30, 2004, accessed February 9, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c Wulf D. Hund: Alienated bodies. transcript Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-837-61151-9 , p. 81 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Erich Sommerauer: Angelo Soliman ( archive link ( Memento of the original from July 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. )

- ^ Hannes Leidinger , Verena Moritz , Bernd Schipper: Black Book of the Habsburgs. An inglorious story of a ruling house . Franz Deuticke, Vienna / Frankfurt / M. 2003, ISBN 3-216-30603-8 , p. 189

- ↑ Angelo Soliman. In: habsburger.net. Retrieved February 9, 2016 .

- ↑ "There are many Angelo Solimans". In: derStandard.at. September 30, 2011, accessed December 9, 2017 .

- ↑ http://freimaurer-wiki.de/images/thumb/7/77/Angelo_Soliman.jpg/250px-Angelo_Soliman.jpg

- ^ Paul Jandl: Baroque: How a slave from Africa made a career in Vienna. In: welt.de . December 19, 2011, accessed October 7, 2018 .

- ↑ numer. Bibliography

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Soliman, Angelo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian valet of African origin |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1721 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nigeria |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 21, 1796 |

| Place of death | Vienna |