Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross

| Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross

|

|

|---|---|

The intermediate archive in Satigny |

|

| Archive type | Archive of an international organization |

| place | Geneva |

| Visitor address | Avenue de la Paix 19 |

| founding | 1863 |

| carrier | International Committee of the Red Cross |

| Website | https://www.icrc.org/en/archives |

The archive of the International Committee of the Red Cross ( ICRC ) has its headquarters in Geneva and was founded there at the same time as the humanitarian organization was founded on February 17, 1863. It has the dual function of managing documents that are still up-to-date as an interim archive until their retention period has expired and, as a historical archive, to preserve their historically relevant holdings. The latter are open to the public for the years up to 1975.

Together with the associated ICRC library at its Geneva headquarters, the archive houses one of the world's largest collections of documents on international humanitarian law . The Swiss writer Nicolas Bouvier described the archive as a “storehouse of mourning”, as it holds information on the fate of many millions of victims of armed conflict as the “legacy of humanity” .

history

Foundation phase

On February 17, 1863, five men - the businessman Henri Dunant , the lawyer and philanthropist Gustave Moynier , the two doctors Louis Appia and Théodore Maunoir, and General Guillaume Henri Dufour - founded the ICRC's predecessor association in a private apartment in the old town of Geneva. The house where the meeting took place was known as the "Old Casino". The main initiator, Dunant, signed the minutes of the committee's meeting as secretary and, with this first document, also laid the foundation for the organization's archive and library.

The actual seat of the ICRC - and thus also of the archive and library - was Dunant's private residence in the “Maison Diodati ”. His family's house at 4 rue du Puits-Saint-Pierre in the old town, where he had already written his seminal book “ A Memory of Solferino ”, remained the main address for a decade.

In those years the archive concentrated on following the implementation of international humanitarian law, in particular the Geneva Convention of 1864. This included reports on the German-Danish War of 1864 between Prussia and Austria on the one hand and Denmark on the other national affiliation of the Duchy of Schleswig . Another focus was the Franco-German War of 1870/71. The holdings of the Basel agency with files on prisoners of war from this war - a total of 12 linear meters - were taken over by the ICRC archive in the following years. The same applies to the documents of the Trieste Agency on prisoners of war during the Balkan crisis (1875–1878), albeit only with a circumference of one linear meter.

When the ICRC moved into its new headquarters at 3 rue de l'Athénée on the edge of the old town in 1874, the archive, consisting of just two bookshelves, moved from Dunant's private apartment into the three-room apartment that served as an office. For the next four decades, the archive primarily collected diplomatic correspondence on his mandate. At the same time, it documented the emergence and growth of the worldwide International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Nevertheless, the old stock for half a century until 1914 - the ancien fund - has a modest extent of 8 linear meters.

First World War

The outbreak of World War I also marked a turning point for the ICRC - and thus also for its archives: under the leadership of its President Gustave Ador , the committee founded the International Central Agency for Prisoners of War (IPWA). Their main task was initially to register prisoners of war and to re-establish contact with their families. By the end of 1914, the IPWA had around 1200 volunteers, including many young women and students. The agency was based at the Musée Rath art museum in Geneva .

The IPWA mandate was based on the 6th resolution of the 9th Washington Conference of 1912 and was restricted to military personnel. However, right from the start, the agency received numerous inquiries about the whereabouts of civilians in occupied territories, etc. The doctor Frédéric Ferrière , who had been a committee member since 1884, therefore founded a private civilian section of the IPWA against the advice of other ICRC leadership members, which in operated in a vacuum under international law. However, it was soon generally identified with the ICRC and contributed significantly to its positive reputation, which was honored with its first Nobel Peace Prize in 1917 . Henri Dunant, who was quickly ousted from the ICRC by Moynier and largely forgotten as a poor man, had already received the award in 1901.

One of the hundreds of volunteers in the civil private section was the French writer Romain Rolland , who worked there from October 1914 until July the following year. When Rolland received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915 , he donated half of the prize money to the Central Office, thereby giving it the appropriate attention. The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig described the work of his friend as follows:

" A small, unplaned desk with a bare wooden armchair in the middle of the crowd of an unadorned, boarded-up cabin, next to pounding typewriters, pushing, calling, hurrying, questioning - that was Romain Rolland's battleground against the misery of war. Here he tried to reconcile what the other poets and intellectuals agitated against one another through hatred, through good concern, to alleviate at least a fraction of the millionfold torture through occasional calming and human consolation. He neither desired nor held a leading position in the Red Cross, but, just like the other nameless people there, took care of the daily work of communicating information: this act of his was invisible and therefore doubly unforgettable . "

The filing system for the millions of index cards was designed by the archivist and palaeographer Étienne Clouzot (1881–1944), who became director of one of the Entente departments. He was also a columnist for the liberal daily Journal de Genève , which for its part once contributed indirectly to the establishment of the ICRC with the publication of an anonymous report by Henry Dunant on the Battle of Solferino - which once more its traditional intertwining with the upper class of the Calvinist city or the canton illustrated.

Between the world wars

At the end of 1918, the ICRC - and with it its archive and library - moved into new headquarters on Promenade du Pin 1 on the edge of the old town. In the following year Clouzot (see above) became director of the ICRC secretariat and thus also took on responsibility for the archive and library.

After a few years in which the ICRC experimented with a variety of archiving methods, the Secretariat introduced a two-part filing system in the early 1920s. This consisted of an archive group for legal, diplomatic and administrative matters and one for operations under the leadership of the Delegation Commission for Missions.

The IWPA only existed until 1924, but the archive collected more information on various conflicts, some of which can be seen in continuity with the First World War, including:

- the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922),

and after a comparatively quiet decade

- the Chaco War (1932-1935),

- the Abyssinian War (1935-1936),

- the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and

- the Second Sino-Japanese War (from 1937).

It was not until 1930 that the ICRC began to systematically create and store its own personnel files, which reflected the rapid growth in activities and responsibilities.

1933 moved the ICRC - and thus once again be archive and library - a new headquarters for the first time in its history, away from the Geneva's Old Town: the Villa Moynier within the large Parc Moynier on the western shore of Lake Geneva was in 1848 for the banker Barthelemy Paccard built and his son-in-law Gustave Moynier (1826-1910), who was the first ICRC president to remain in office for a record 47 years until his death. In 1926 the house served as the seat of the League of Nations . The ICRC stayed there until 1946/7.

In these two decades between the world wars, with a view to the archive, there was also an increasing awareness within the ICRC for a culture of remembrance in the sense of a humanitarian memory of humanity and humanity.

Second World War

Just two weeks after the start of the Second World War , the International Central Office for Prisoners of War was reopened, now based on the Geneva Conventions in the version of 1929 .

The archivist Étienne Clouzot, who worked out the rules for archiving at the IWPA during the First World War, helped set up the new agency structure in 1939 and devoted himself to it during the last five years of his life. Suzanne Ferrière played a prominent role in the civilian sector. She had already assisted her uncle Frédéric during the First World War and now established a new message transmission system for family members.

As a result of the millionfold suffering, the number of file processes also multiplied with a total of around 45 million index cards and around 120 million messages conveyed. As early as October 1939, the ICRC received punch card technology and staff from IBM free of charge to automate classifications and other information processing . In view of the flood of data that was handled by around 3,000 employees, the archive introduced a new filing system in 1942. The efforts were honored with a second Nobel Peace Prize in 1944.

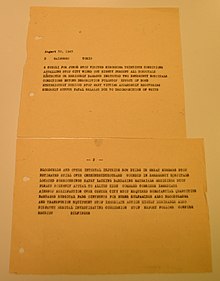

One of the last - and at the same time most haunting - documents in the archive from the time of the Second World War was created a few days before the end of the war: on August 29, 1945, the ICRC delegate Fritz Bilfinger described the ruins of the Japanese city of Hiroshima just three weeks after the atomic bombing there The US was the first foreigner to reach the apocalyptic situation in a telegram , warning of the dangers of the atomic age .

Decolonization and the "Cold War"

One year after the end of the Second World War, the ICRC moved its headquarters and archive from the Villa Moynier to the former Carlton Hotel. The canton of Geneva made the neoclassical building on a hill above the Palace of the League available to the organization as part of a long-term lease.

At the same time the archive was upgraded to a separate department within the ICRC. Jean Pictet (1914–2002) was responsible for this step , a lawyer who specialized in international humanitarian law and is also considered the spiritual father of the 1949 Geneva Convention on the Protection of Civilians in Times of War. As director of the main administrative department, Pictet, who came from an old banking family in Geneva, then introduced a new and comprehensive filing system in 1950. The numbering was now based on both thematic and geographical references. All files of the entire organization were organized according to the "Pictet Plan" until 1972. In the archive department itself, it was even valid until 1997.

In the meantime, the files in the archive continued to grow by leaps and bounds. The cause was numerous conflicts that broke out in the course of decolonization and in the context of the so-called Cold War - which was a hot war in many areas, especially in the global south. These included in particular:

- the Indochina War between France and the Việt Minh (1946 to 1954)

- the Nakba in Palestine (1948)

- Suez crisis and Hungarian uprising (both 1956)

- the Korean War (1950 to 1953)

- the Algerian War (1954 to 1962)

- the Congo crisis (1960 to 1965)

- the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962)

- the North Yemeni Civil War (1962 to 1970).

Against this background, the ICRC received its third Nobel Peace Prize in 1963 after 1917 and 1944, which also made it the institution with the largest number of these awards to date. The International Central Office for Prisoners of War had already received permanent status within the ICRC three years earlier as the central tracing service, which meant that the relevant documents were also permanently linked to the archive. Strengthened accordingly, the organization developed even larger activities in a growing number of conflicts in the following years, including:

- the Vietnam War (1964 to 1975)

- the Six Day War of 1967

- the Biafra War in Nigeria (1967 to 1970)

- the Greek military dictatorship (1967 to 1974)

- the 1973 coup against President Salvador Allende in Chile

- the Yom Kippur War of 1973

- the Cyprus conflict of 1974

- the end of the Portuguese colonial empire and the wars of independence in Angola and Mozambique (1975) as well

- the genocide in Cambodia (1975 to 1979) and the Cambodian-Vietnamese War (1978 to 1989).

Until 1973, the public was generally denied access to the files in the ICRC archives, even if the Board of Directors was able to grant exceptional permits in individual cases. This procedure was not formalized until 110 years after the founding of the organization, which was a first step towards opening the archives. However, the ICRC continued to strictly determine the selection of documents to be viewed, which was increasingly criticized as arbitrary by research.

When the US TV mini-series " Holocaust - The History of the Weiss Family " sparked a broader debate in Switzerland about involvement in the Nazi regime of terror in 1979, the public discourse also began to criticize the role of the ICRC. This particularly concerned the fact that the ICRC had not denounced the Nazi concentration camp system .

Against this background, the ICRC set a precedent under its new president Alexandre Hay in 1979 by granting the Geneva history professor Jean-Claude Favez unrestricted access to the relevant documents for his study of the ICRC's policy during the Holocaust . The book did not appear until 1988, but it still meant a breakthrough in dealing with the ICRC past in particular and also in coming to terms with Swiss history in general. The work was published in German a year later under the title "The International Red Cross and the Third Reich - Could the Holocaust be stopped?" released.

The fact that the archive moved into a new office building next to the historic “Le Carlton” building in 1984 was symbolic of the dawn of modern archive technology.

The driving force behind the further opening of the files was now Cornelio Sommaruga , who was elected Hays successor to the office of ICRC President in 1987 and had previously been State Secretary for Foreign Trade. Nevertheless, it was not until the end of the “Cold War” that the assembly of committee members sanctioned the goal of better access to historical documents: it was not until May 1990 that the decision was made to give the archives department a mandate that complied with the “Principles of a modern archival system ». Nonetheless, the ICRC insisted on the requirement that texts be presented before publication and reserved the right to delete passages.

Since 1990

It took another six years before the ICRC assembly in January 1996 recognized the general public's right to access the archives. The periods of protection were set at fifty years for general files and one hundred years for personal records. Numerous voices within the ICRC had previously spoken out in favor of even longer closing times. In the following year, the general files for the years 1863 to 1950 were made fully available to the public, almost 500 linear meters in total.

The French historian Serge Klarsfeld and his organization "Association of the Sons and Daughters of Jews Deported from France" were among the first to show their interest in systematic research . Two years later he published a collection of documents from the archive on the internment and deportation of French Jews during the Second World War.

In 1997, almost half a century after the “Pictet Plan”, the archive introduced a new filing system called “B AI” ( Services généraux - Archives institutionalnelles ), which was also suitable for digital documents.

In 2004 the archive made another part of its tradition accessible to the public, again around 500 linear meters. These were the general files for the years 1951 to 1965. In the same year the ICRC assembly shortened the blocking period for these files from 50 to 40 years and for personal files from 100 to 60 years.

In 2007, the United Nations Organization for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO) included the archive in its directory for world document heritage - as the first institution in Switzerland and the first international organization at all. The UNESCO program is intended to counteract collective memory loss , promote the preservation of archives and libraries, and ensure the widest possible dissemination of their collected knowledge.

In 2008/9, the ICRC administration building from 1984, which also houses the archive, was expanded with the construction of a modern rotunda , which also serves as a representative reception hall for the users of the archive.

In 2010, the public archive was merged with the ICRC library and the ICRC photo archive in the information management department, in order to take into account the ever-increasing development of digital technologies, the growing complexity of very large amounts of data on the one hand and the fragmentation of information on the other to encounter. In the same year, the ICRC introduced a new filing system called "B RF" ( Services généraux - Archives générales des unités, Reference Files ). The new department has since various automation processes implemented, including, more recently, the application of artificial intelligence to the institutional memory to preserve.

As part of this modernization, the archive expanded in 2011 into the logistics center of the ICRC. The new building in Satigny, not far from Geneva Airport , was partially financed by the Swiss Federal Council , and the land in an industrial park was made available by the Canton of Geneva . Satigny serves primarily as an interim archive and as a warehouse for the stocks that are still blocked. The public for the main archive and library will therefore continue to take place at the Geneva headquarters.

In 2015 the archive released a third batch of general files. These files cover the years from 1966 to 1975 and include documents relating to the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela . Two years later, however, the ICRC assembly decided to increase the embargo period by ten years to take account of the growing phenomenon of protracted conflicts. According to this line of argument, historical documents can have a very current impact, because the actors in such conflicts are often the same, and thus undermine the principle of confidentiality as the basis of ICRC activities. The new rules mean that general documents are locked again for 50 years and personal files for 70 years. As a result, the next tranche of general written material for the years 1976 to 1985 will not be released until 2035.

Holdings and collections

The public and audiovisual collections are divided into five sub-areas:

- The general public archives contain records covering the history of the ICRC from its establishment in 1863 to 1975. They are mainly written in French .

- The holdings of the Central Tracing Service with documents on individuals are generally open for the period up to the 1950s. However, most research requests can only be made through the responsible specialists in the archive. The only exception are the index cards for the approximately two million prisoners of war of the First World War with information from. a. on arrests, renditions from camp to camp and death dates. They have now been digitized and put online. These are primarily events on the western front , the front in Romania and the Serbian campaign (documents on other sections of the front are kept by the Danish Red Cross). Inquiries about prisoners of war and interned civilians, however, have to go through a special procedure. Although this is in principle open to all applicants, the archive only accepts a certain number of applications per year for reasons of capacity. The archive is only open to family members for questions about the whereabouts of individuals who have disappeared in recent conflicts.

- The picture archive contains over 800,000 photos on the international ICRC activities since the 1860s. Around 125,000 have already been digitized and made available to the public.

- The film archive consists of around 5,000 titles with a total of around 1,000 hours of material on the humanitarian work of the ICRC since 1921. A large number of formats ( video cassettes , 35mm film and 16mm film ) have been digitized for this purpose.

- The audio archive has a stock of over 10,000 files with around 1,000 hours of digitized material that has been recorded since the second half of the 1940s.

In addition to the institutional traditions, the holdings also include private collections that former members of the committee and delegates left or left to the archive.

The holdings of the ICRC archive include - as of early 2020 - approximately:

- 9 million electronic documents ,

- 19 running kilometers of shelves with paper documents,

- 34 terabytes of electronic media in the Audivision division , and

- 41 million index cards on individuals from the two world wars.

The ICRC library contained around 41,000 titles in its catalog at the same time, including:

- preparatory documents, reports, records and minutes of diplomatic conferences on international humanitarian law treaties;

- Notes from Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement Conferences on International Humanitarian Law;

- all issues of the journal " International Review of the Red Cross " or its predecessors since its inception and all other ICRC publications;

- rare documents published in the decades between the founding of the ICRC and the First World War, particularly on Dunant's ideas; and

- a unique collection of legal writings on issues of international humanitarian law.

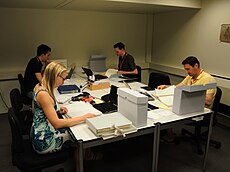

The archive and library are visited by an average of around 1,500 researchers each year. In 2019, the archives recorded approximately 1.4 million page views from their various online platforms. During the same year, the archive staff handled approximately 11,000 inquiries, both external and internal.

gallery

- The central office for prisoners of war in the Rath Museum during the First World War

- The central office for prisoners of war in Plainpalais during the Second World War

- The public archive at Geneva headquarters (since 1984)

- The non-public archive in Satigny (since 2011)

See also

Web links

- The archive site (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Valerie McKnight Hashemi: A balancing act: The revised rules of access to the ICRC Archives reflect multiple stakes and challenges . In: International Review of the Red Cross . tape 100 , no. 1-2-3 , 2018, pp. 373–394 , doi : 10.1017 / S1816383119000316 (English, icrc.org [PDF; 223 kB ; accessed on June 18, 2020]).

- ↑ a b c d e f United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization - UNESCO (Ed.): Guide to the archives of intergovernmental organizations . Paris 1999, p. 127-134 ( unesco.org ).

- ↑ a b c LIBRARY. In: International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved June 18, 2020 .

- ^ Didier Helg: Focus on Humanity A Century of Photography The ICRC Archives - Nicolas Bouvier, Michèle Mercier and François Bugnion, Focus on humanity. A century of photography. Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Skira, Geneva, 1995 . In: International Review of the Red Cross . tape 35 , no. 308 , October 1995, p. 579-580 , doi : 10.1017 / S0020860400089695 (English).

- ↑ a b c Roger Durand, Michel Rouèche: Ces lieux ou Henry Dunant ... Those Places Where Henry Dunant ... Ed .: Société Henry Dunant. Geneva 1986, ISBN 978-2-88163-003-3 , pp. 36-43, 54-55 (French).

- ↑ a b c d Jean-François Pitteloud: New access rules open the archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross to historical research and to the general public . In: International Committee of the Red Cross (Ed.): International Review of the Red Cross (314) . October 31, 1996 (English, icrc.org ).

- ^ Jacques Chenevière: The First "Prisoners of War Agency" Geneva 1914-1918 . In: International Committee of the Red Cross (Ed.): International Review of the Red Cross . tape 75 , June 1967 ( icrc.org [accessed June 23, 2020]).

- ^ Stefan Zweig: Romain Rolland; the man and his work . T. Seltzer, New York 1921, p. 268–270 (English, archive.org [accessed June 22, 2020]).

- ^ Adolphe Ferrière: Le Dr Frédéric Ferrière. Son action à la Croix-Rouge internationale en faveur des civils victimes de la guerre . Editions Suzerenne, Sarl., Geneva 1948, p. 27–41 (French, nexgate.ch [PDF]).

- ↑ Nicole Billeter: Words against the desecration of the spirit !. War views of writers who emigrated from Switzerland in 1914/1918 . Peter Lang Verlag, Bern 2005, ISBN 3-03910-417-9 .

- ^ Paul-Emile Schazmann: Romain Rolland et la Croix-Rouge . Ed .: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (= Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge et Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge ). February 1955 (French).

- ^ Stefan Zweig: Romain Rolland . S. Fischer, 2009.

- ↑ a b c d e Ismaël Raboud, Matthieu Niederhauser, Charlotte Mohr *: Reflections on the development of the Movement and international humanitarian law through the lens of the ICRC Library's Heritage Collection . In: International Review of the Red Cross . tape 100 , no. (1-2-3) , 2018, pp. 143-163 , doi : 10.1017 / S1816383119000365 (English).

- ↑ Henry Dunant: Faits diverse. In: Journal de Genève. July 9, 1859, accessed July 16, 2020 (French).

- ^ Death of Miss S. Ferriere, Honorary Member of the ICRC (= International Review of the Red Cross ). Geneva April 1970, p. 210-211 (English).

- ^ The ICRC and the private sector. (PDF) In: International Committee of the Red Cross. December 6, 2016, p. 20 , accessed July 20, 2020 .

- ↑ Vincent Bernard and Ellen Policinski: Nuclear weapons: Rising in defense of humanity. In: Humanitarian Law & Policy. March 17, 2017, accessed on July 31, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c Chapter 10: The ICRC: An architecture of emergency. In: Genève internationale. Retrieved June 24, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c ICRC archives to be opened, 1966–1975. In: INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS. June 10, 2015, accessed June 23, 2020 .

- ^ A b Jean-François Pitteloud: The International Committee of the Red Cross reduces the protective embargo on access to its archives . In: International Review of the Red Cross 86 (856) . 2004, p. 958-962 , doi : 10.1017 / S1560775500180538 (English, icrc.org [PDF]).

- ^ Jean-Claude Favez and Genevieve Billeter: The International Red Cross and the Third Reich - Could the Holocaust be Stopped? Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 1989, ISBN 978-3-85823-196-3 .

- ↑ George W. Baer: International Organizations, 1918-1945: A Guide to Research and Research Materials . Scholarly Resources, Wilmington 1993, ISBN 978-0-8420-2309-2 , pp. 33-34 .

- ^ New book on ICRC's role during Second World War. In: International Committee of the Red Cross. December 17, 1999, accessed July 27, 2020 .

- ^ Caroline Stevan: The archives du CICR inscrites à la Mémoire du monde de l'Unesco . In: Le Temps . November 16, 2007, ISSN 1423-3967 (French, letemps.ch [accessed August 8, 2020]).

- ^ The International Prisoners-of-War Agency: The ICRC in World War One. (PDF) International Committee of the Red Cross / Musée international de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge., 2007, accessed on August 8, 2020 (English).

- ↑ a b c d Brigitte Troyon Borgeaud: Le CICR: un service qui s'adapte à l'environnement informationnel (= ". Arbido - The specialist journal for archives, libraries and documentation ). 2020 (French, arbido.ch [accessed on 26 June 2020]).

- ^ Inauguration of ICRC's new logistics hub. In: Genève internationale. September 14, 2011, accessed June 26, 2020 .

- ^ Brigitte Troyon Borgeaud: Rules governing Access to the Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross - Adopted by the Assembly of the International Committee of the Red Cross on March 2, 2017. In: International Committee of the Red Cros. May 3, 2017, accessed June 26, 2020 .

- ^ Contacting the ICRC archives. In: INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS. January 3, 2017, accessed on July 17, 2020 .