Arete

The ancient Greek word arete ( ancient Greek ἀρετή aretḗ ) generally denotes the excellence of a person or the excellent quality and high value of something. People mean efficiency, especially in the military sense (bravery, heroism). Often associated with this is the idea that the capable is also successful. Initially, Arete appears as an exclusive ideal of the nobility. The term was later taken up by broader strata, especially in the education-oriented urban upper class. This leads to a change in meaning: Social skills - especially civic qualities and political leadership skills - come to the fore.

In ancient philosophy , Arete as " virtue " was a central concept of virtue ethics . The different philosophical schools almost all agreed on the assumption that a successful lifestyle and the associated state of mind eudaimonia require possession of the arete. Some philosophers even thought that eudaimonia consists in the arete.

etymology

The origin of the word is unclear. In the Middle Ages it was etymologically derived from the verb areskein (“to like”, “to satisfy”), and this etymology was also widespread in the older research literature . According to current research, there is no direct connection with this verb, but arete is associated with areíōn , the comparative of agathós ("good"). In archaic times, agathos primarily referred to the fighting ability of the man who was considered "good" if he fought valiantly when making statements about people. Such a fighter belonged to a social elite, he was respected, noble and usually wealthy, therefore agathos could also mean "noble". Accordingly, the comparative areion had the main meaning " braver , stronger, more capable (in battle)".

Arete in common usage

In the common parlance of the ancient world , arete denotes the ability of a person to fulfill their particular tasks or the suitability of a thing (including an animal or a part of the body) for the purpose it is intended to serve. For example, a knife, an eye or a horse can have arete. In the case of people, arete consists of a set of characteristics that distinguish the person and give him excellence. The common pattern is the heroic ideal shaped by Homeric poetry, which consists of a combination of intellectual and character qualities with physical advantages. The hero embodies this ideal in his life and in his death; the arete enables him to achieve outstanding achievements that bring him fame. Aspects of "efficiency" are practical wisdom, bravery and also physical strength. The capable hero has energy and assertiveness. His efforts are usually rewarded by success, but disaster can also hit him. Homer's gods also have an arete, and he also has an arete of women, which is fundamentally different from the male arete.

In German, when it comes to the meaning in non-philosophical ancient language usage, Arete can be rendered as “being good” (in the sense of a high degree of suitability). The common translation with “virtue” is misleading and therefore very problematic, because the basic meaning does not mean virtue in a moral sense (although this can also be implied in individual cases). Arete is only consistently understood morally in philosophy.

In Homer's case, Arete is exclusive to arete; she is alien to the common people. For Hesiod, however, there is also an arete of hardworking farmers. By this he means not only their efficiency, but especially the prosperity, the success of their work , which is reflected in wealth and prestige. For Hesiod, Arete is inseparable from success.

The warlike Arete is praised by the Spartan poet Tyrtaios , for whom the willingness to die is particularly important. Similar ideas can be found in verses handed down under the name of Theognis (Corpus Theognideum). There, as with Tyrtaios, the achievement is emphasized which the able renders for the state. It is no longer the outstanding individual performance, as in Homeric individual combat, but the endurance in the battle line that defines the arete of the brave warrior in the civil army. In the Corpus Theognideum an Arete ideal is propagated, which particularly places justice as a nobility-specific virtue in the foreground. The non-nobles (democrats), who have suppressed the influence of the nobility in the state, are accused of a lack of arete. The poet laments the lack of understanding of his contemporaries for the traditional arete. He insinuates that they are only interested in wealth. He also considers this to be an aspect of the Arete, but proficiency should not be reduced to the existence of property. Justice, bravery, worship of gods, prudence and practical wisdom are also important .

At Pindar , the arete shows itself in sporting competition; on the one hand it is a matter of disposition, on the other hand such “skills” are also learned. Pindar Arete also names the performance. For the lyricist Simonides von Keos , arete and success are inseparable; whoever remains unsuccessful - even through no fault of their own - has no arete, but is "bad".

In the archaic and classical times , rule was legitimized by the fact that the ruler could show that he had a particularly high level of arete. Since such efficiency and virtue were considered hereditary, those in power used to trace their descent to a mythical hero using a fictitious genealogy . But this was not enough, the ruler had to prove his arete through his actions and thus show that his claim to have a hero as an ancestor was credible. It was believed that one so qualified was naturally entitled to rule. Anyone who demonstrated their rulership through deeds, for example through military achievements, through victories in Panhellenic competitions or through the great deed of founding a city, was willingly submitted to them.

In the time of Hellenism , as honorary decrees show, the arete was associated in particular with civic virtues. It manifested itself specifically in services for the common good from philanthropic generosity, such as the private financing of public construction activities, or in artistic contributions to festivals. Special political and diplomatic merits were also recognized by the state as a symbol of Arete. The honorary inscriptions presented the citizenship as a role model for the efficiency and generosity of benefactors. For the state community, the public praise of exemplary Arete also had an identity-creating effect.

Arete was personified literarily and poetically only occasionally in antiquity; In contrast to the Roman virtus , there was no cultic worship as a deity. Representations of the personified Arete can be found in the visual arts.

sophistry

In the second half of the 5th century BC In Greek cities, especially in Athens , a broad and intensive striving for education made itself felt in the upper class. To satisfy the educational needs , hiking teachers were active, who gave lessons for a fee. The educational offerings of the traveling teachers, for whom the term " sophists " became natural, was based on practical goals. Knowledge and skills should be imparted which enable active, successful participation in state life and the legal system. The aim was to develop an arete that was no longer understood in the sense of conventional aristocratic ideals, but was promised to everyone capable of learning. The arete meant by the sophists and their numerous disciples could be conveyed verbally. It was about knowledge, about a qualification that would ensure success for the sophistically trained and give them a corresponding social rank. Success, which had already been part of the traditional aristocratic ideal of proficiency, was the central aspect of the arete at which the sophistic teaching aimed. The students particularly wanted to acquire political assertiveness.

The Sophists' claim that Arete was teachable was not generally accepted but met with opposition. The opposing position was that Arete was a matter of disposition or that it could only be obtained through one's own efforts without external assistance. Those who hold this view argued that there are no qualified Arete teachers; In contrast to medicine, for example, one cannot distinguish between specialists and laypeople. Famous, exemplary men such as Pericles and Themistocles did not succeed in imparting their own arete to their sons, rather the sons had proven to be inefficient. Many students of the sophists could not have acquired the Arete in class, but were unsuccessful, and some had distinguished themselves through Arete without having received appropriate training.

Arete in philosophy

All ancient schools of ethics, with the exception of the Cyrenaics, viewed Arete as a means of attaining the desired state of eudaimonia, or even an essential element of that state. It has even been suggested that Arete is what constitutes all of eudaimonia. Eudaimonia is understood to mean a good, successful lifestyle and the associated state of mind. The term is usually imprecisely translated as "happiness" or "bliss"; but it is not a question of a feeling.

Socrates

For Socrates , whose thinking revolved around the right way of life, the arete was a central philosophical term, the content of which was of moral quality. This arete can therefore be represented as “virtue”. Socrates believed that leading a virtuous life was the highest goal of every human being. How he dealt with this issue in detail cannot be determined with any certainty. What is known is only what the literary “Platonic” ( appearing in Plato's dialogues ) Socrates said. The question of the relationship between the Platonic Socrates and Socrates as a historical personality is unanswered, a convincing reconstruction of the philosophy of historical Socrates is considered impossible today.

According to the view of the Platonic Socrates, which Plato himself shares, man should primarily not care about what “belongs to him”, but about “himself”. What belongs to you means your own body, which is perceived as something external that is not part of the actual “self”. Even further from the self are external goods such as possessions, prestige, and honor. The self that is to be cared for, to be done “as good and sensible as possible” is the soul . It is the bearer of ethical responsibility, the Arete consists solely in its “goodness”. Whoever does morally good lives properly and attains eudaimonia. The only prerequisite for this is that one recognizes what is morally good. This prerequisite is not only necessary, but also sufficient, because whoever knows what good is, will inevitably always do it. Thus virtue is based exclusively on knowledge, for from the knowledge of the good it is imperative that a life according to the Arete results. With knowledge it is meant here that the knower has not only understood what a virtuous life is, but also understands that such a life is the basis of eudaimonia and is therefore in his own best interest. If one has not only mentally understood this insight, but has internalized it completely, then one can no longer act against one's own interest. Behavior contrary to virtue is no longer possible. External circumstances - such as the threatened loss of external goods such as property and reputation and even danger to life - cannot dissuade those who live according to the Arete from their decisions. Since the possession of external goods is not necessary for his eudaimonia, but it is based exclusively on the arete, he can easily do without the external goods, but by no means on the arete.

The Platonic Socrates is convinced that knowledge of virtue can be acquired and imparted to others. For him, Arete is basically teachable and recognizable through your own reflection, if you have the appropriate disposition. With regard to the practical implementation of the theoretical principle of teachability, however, he expresses himself skeptical, since the nature of the Arete has not been sufficiently clarified. In his argument with the sophist Protagoras , he even denies the teachability, but there he argues against it not in principle, but only empirically. His aim is to review the claims of sophists like Protagoras to be teachers of the Arete. The principle of teachability apparently also contradicts the historical Socrates' conviction that he himself - like everyone else - is a ignoramus (distorting short formula: I know that I know nothing ). In fact, the historical Socrates apparently emphasized that he had no irrefutable “knowledge” in the sense of a knowledge of truth based on compelling evidence. In this sense, Plato lets Socrates state that he does not know what Arete is, nor does he know anyone who does. However, Socrates could regard virtuous knowledge as a type of knowledge if he started from a different understanding of knowledge (knowledge in a weaker sense). According to this meaning, it is a certainty that arises when all attempts at falsification have failed. The view of the Platonic Socrates of the teachability of virtuous knowledge is therefore compatible with the epistemological skepticism of the historical Socrates and can have been represented by him.

The view of the Platonic Socrates, that there is no specifically male or female virtue, but that virtue is the same for all people and that there is no difference between the sexes in terms of their accessibility, probably goes back to the historical Socrates.

Plato

In his dialogues, Plato also allows Socrates to take positions that specifically presuppose Platonic ideas and therefore cannot be related to historical Socrates. This includes statements about the Arete or about individual virtues within the framework of the Platonic theory of the soul and the theory of ideas .

Non-philosophical and philosophical aretes

Plato worked out his own doctrine of virtues, including traditional and common aspects of the meaning of the term Arete and dealing with conventional views. He distinguishes a true arete based on reasonable insight, which the philosopher realizes, from widespread ideas of virtue of various kinds, which in his view are only partially correct or even completely erroneous. Correct behavior that is not philosophically founded and considered virtuous can be based on habit and upbringing or on a natural disposition or result from calculating the consequences of actions. Plato does not reject such a motivated practice, but examines it critically and in some cases grants it justification. In this way he recognizes the value of correct civic behavior by non-philosophers, which is essential for the continued existence of the state. Although philosophically uneducated people practice what they consider virtue not for its own sake, but because they strive for fame and orientate themselves to a socially accepted value system without critical reflection, their work can still be useful. Since such ideas of virtue are not based on knowledge, they are not real virtues. They are just opinions that can be correct without their advocates understanding why they are correct.

In terms of the general Arete term (“goodness”, “suitability”), which also refers to animals and objects, Plato regards Arete generally as the realization of the essence of the good, suitable thing or the virtuous person. The bearer of the Arete realizes his being when he is as he should be according to his own nature and purpose. In this state, the person or thing in question can optimally perform its specific task and play the role that it naturally has to play.

The question of teaching development

It is unclear to what extent Plato, in the course of his philosophical development, distanced himself from the originally simple and radical theses of the Socratic approach and adopted more differentiated positions. This includes the question of whether he adhered to the absolute insignificance of external goods and circumstances such as health and success for eudaimonia, or whether he gave them a role, albeit a minor one. In the dialogue Politeia he lets Socrates point out that external goods can be helpful in perfecting the soul. Even the radical assertion in early dialogues that the practice of virtue inevitably results from the knowledge of virtue and that ignorance is the only reason for doing injustice, Plato seems to have relativized through restrictions in the course of developing his theory of the soul. In presenting the doctrine of the soul, he deals in detail with the existence and influence of the irrational in the soul and takes into account the inner-soul conflicts between reason and irrational factors. In doing so, he grants the possibility that, despite existing knowledge, an irrational soul authority can temporarily prevail and physical affects can also impair judgment. But such divergent statements are not necessarily to be interpreted as contradictions or evidence of a change of opinion. Rather, it must be taken into account that in the various dialogues, depending on the conversation situation and conversation strategy, different points of view are emphasized or emphasized one-sidedly.

The basic virtues and their unity

Plato adopted four basic virtues, known as the cardinal virtues since the Middle Ages : prudence (sōphrosýnē) , bravery (andreía) , justice (dikaiosýnē) and wisdom ( sophía or phrónēsis ). Outside this four-way scheme is piety (hosiótēs) , which is also an important virtue. Justice ensures the harmonious relationship of the other three basic virtues. In the soul every virtue has its area of responsibility in which it should rule. Justice is the virtue of the whole soul, it structures the whole system and maintains the inner soul order. The other basic virtues are assigned to the three parts of the soul: wisdom is the uppermost part, logistikón (reason), bravery is thymoeidés , the "courageous" (ability to affect), prudence is epithymētikón , the instinctual part, which forms the lowest part of the soul. The instinctual part of the soul, which is arranged for the satisfaction of body-related lust, resembles a wild animal. He is supposed to submit to what reason has to take care of with the support of courage, and requires strict guidance.

In addition to the virtues acquired through philosophical knowledge, there is also a personal disposition to one or the other virtue. It must be regulated through upbringing so that there is no one-sidedness and disturbs the inner order of the soul.

The question of the unity of virtues plays an important role. It is discussed in the dialogues, but not clarified. One fact that suggests unity is that all virtues are aimed at good and require knowledge of the difference between good and bad. The nature of the unity according to Plato's understanding is, however, unclear. In research it has been discussed whether the unity can only be understood as a weak identity or whether one can speak of a strong identity. A weak identity arises from the assumption that the virtues are so closely related that if you have one of them you also have the others. In addition, there is a strong identity when there are only four terms of the same virtue, the terms referring to different aspects of the practice of that virtue. Whether Plato considered the latter to be correct remains open. He only represents an at least weak identity with regard to the real virtues, that is, the virtues of the philosopher, because in non-philosophical people, for example, bravery can occur without wisdom. For Plato, such bravery is not a virtue in the strict sense.

Doctrine of ideas and virtues

In principle, Plato's theory of ideas opens up the possibility of direct, non-discursive access to Arete. The ideas, the unchangeable archetypes of the individual things, are objective realities according to the theory of ideas, which can be recognized by appropriately trained people through perception. This purely mental process is described metaphorically as a vision in analogy to sensory perception . In the Dialog Symposium , a step model of the ascent to the perception of purely spiritual areas that are closed to the senses is presented - albeit without express reference to the theory of ideas. This ascent culminates in the perception of the primal beauty, beauty in the most general and comprehensive sense, which is ultimately the source of all forms of appearance of the beautiful. Whoever looks at the primal, touches the truth. Therefore he can then “give birth” (from his own mind) and “nourish” the true Arete. He is no longer dependent on the mere shadow images of the Arete, with which he is dealing in the realm of the sensually perceptible, but obtains the Arete himself. With this he qualifies himself to become a “God-Beloved”.

On the one hand, access to the true Arete is a fruit of ascent; on the other hand, virtue - especially justice - is the prerequisite for ascending beyond the realm of imperfect and perishable individual things. Virtue leads man into a divine realm, because it is an imitation of God in the sense of Plato's demand that man should conform to God as far as possible (homoíōsis theṓ kata to dynatón) .

Another link between the doctrine of ideas and the knowledge of virtue results from the fact that within the doctrine of ideas, the knowledge of virtue as knowledge is determined by the ideas of virtues and above all by the idea of the good.

Antisthenes

The philosopher Antisthenes , whose ethical doctrine formed the starting point for the emergence of Cynicism , took up the virtues of his teacher Socrates and added his own ideas. He thought that the Arete could be taught, but that it consists in action and therefore does not need many words; it doesn't depend on theoretical knowledge. The arete is not a privilege of the nobility, but the true nobles are the virtuous. There is no specifically male or female virtue; rather, virtue is the same for everyone. As a norm, virtue is above the existing laws. Although the arete is sufficient for eudaimonia, one also needs the strength of a Socrates. By this he meant that it is not enough to know that eudaimonia lies in virtue. Rather, one can only consistently put this knowledge into practice if one has the equanimity and inner independence of Socrates. Socrates was famous for his modesty, his ability to endure hardship and his independence from the opinions and judgments of others. Whoever strives for arete and eudaimonia must, according to the conviction of Antisthenes, acquire the "Socratic power" by toiling, exposing himself to efforts, eradicating superfluous needs and satisfying the natural elementary needs in the simplest possible way. In particular, the need for recognition and prestige is superfluous; a glorious life is preferable. The traditional connection of Arete with fame and high social status is thus abandoned with Antisthenes and even turned into the opposite. This concept of virtue became groundbreaking for cynicism.

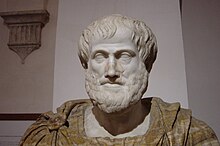

Aristotle

Like Plato, Aristotle sees the criterion for the “goodness” of a person or thing in the quality of their specific creation, their product or their performance. A knife is good when it cuts well, an eye when it sees well. In this sense, a person has Arete when he produces (puts into action) that which corresponds to his natural destiny as a person. For Aristotle this determination is the realization of the human gift of reason through a rational life. For him this is what the arete consists of; only the reasonable living is a good person.

A good, reasonable life presupposes that a harmony is achieved between the reasonable and the unreasonable part of the soul. The unreasonable part, from which the strivings and affects proceed, contradicts the demands of reason, but can be made to submit to it. According to the different functions of the parts of the soul, Aristotle distinguishes between two classes of virtues. The "dianoetic" virtues (virtues of the understanding) wisdom and prudence characterize the rational part of the soul. Wisdom provides people with theoretical knowledge (about metaphysics or mathematics, for example ), while prudence enables them to find out which actions are good and beneficial for them from the point of view of the “good life” (eudaimonia). The “ethical” virtues (virtues of character) ensure that the strivings and affects correspond to what reason demands. Their presence or absence defines a person's character. Aristotle's character virtues include bravery, prudence, generosity, justice, generosity, high-mindedness and truthfulness . He describes them as postures acquired through habituation and denies that they result from an attachment.

In conjunction with prudence, the virtues of character enable people to find the right balance between too much and too little. For example, bravery is somewhere between fear and recklessness. Anyone who is able to strike the right balance in their decisions about action points to Arete in the field of ethics. Basically, Aristotle is of the conviction that the middle between two extremes is the right and reasonable ( Mesotes doctrine).

Aristotle teaches that eudaimonia does not lie in the mere being good, in the possession of the Arete, but in an activity determined permanently by the Arete. By this he means primarily a scientific activity with which theoretical knowledge is obtained and then permanently held in the mind. For Aristotle, contemplating the known truth through a philosophical object of knowledge means perfect eudaimonia. In contrast to practical action, spiritual activity is loved only for its own sake. He considers making it a life's work to be the most perfect realization of man's destiny. Anyone who is not in a position to lead this ideal way of life is dependent on the practical virtues that enable him to have a lower level of eudaimonia. These virtues are secondary because they are purely human. It is ridiculous to think that gods act just, brave, generous, or prudent. The gods do not have to act, only to look. Hence the philosophical consideration is that human activity which comes closest to the work of the divinity. Consequently it also brings about the highest eudaimonia attainable by humans.

However, in Aristotle's opinion, being active in accordance with Arete is not sufficient to realize eudaimonia. Those who do not have certain external goods at their disposal cannot practice certain virtues, and therefore fail to meet the arete in this regard. For example, generosity implies having funds. Thus arete and eudaimonia do not only depend on internal psychological factors, but also on external circumstances over which one has no or only limited influence. The doctrine of the necessity of external goods is a striking feature of the ethics of Aristotle and his school, the Peripatos .

In contrast to Socrates and Plato, Aristotle assumes a difference between the sexes with regard to virtues; he assumes that the basic virtues of men and women are different.

After the capture, torture and execution of his friend Hermeias of Atarneus, Aristotle wrote a hymn to Areta, the personified virtue, in memory of the deceased . He addresses her as a virgin and calls her "laboriously achievable for the human race, most beautiful prey for life". For her sake people like to die in Greece, Hermeias also died for her. According to tradition, Hermeias stood firm under the torture and did not reveal any secrets. From the point of view of his friends and admirers, he proved to be an exemplary virtuous philosopher.

Epicurus

Epicurus undertakes a revaluation of traditional philosophical values. He regards pleasure, which he generally values positively, as the true, natural goal of all action. The highest pleasure for him consists in complete freedom from pain or discomfort. Therefore for him the gain in pleasure - that is, the avoidance of pain - is also the measure by which the virtues are to be measured. The virtues are not the end at which the philosopher's endeavors are aimed, but only means of obtaining pleasure. This means that they are drastically downgraded in importance. As a means, they are necessary for a life free of pain as possible, their justification is not disputed, but a value is only granted to them insofar as they serve the goal of increasing pleasure. For example, courage overcomes fear, which is one of the main sources of displeasure. For Epicurus, who adopted the Platonic scheme of four, the main virtue is prudence; bravery, prudence and justice inevitably spring from it.

Stoa

Zeno of Kition , the founder of the Stoa , took up the Socratic tradition. He admitted to the principles traced back to Socrates that Arete is knowledge and as such can be taught, that it alone constitutes eudaimonia and that virtue inevitably results in the practice of virtue. Zeno only considered the basic virtues of insight (prudence), justice, prudence and bravery to be true goods and the vices opposite to them as true evils; everything else he regarded as ethically irrelevant. He said that the virtues cannot be separated from one another, they form a unit, because justice, prudence and bravery are insights into certain areas of practice and thus forms of expression of insight. The wise man is in permanent possession of virtue and thus of eudaimonia. This property can never be stolen from him. The important Stoic Chrysippos of Soloi followed Zeno's views in the doctrine of virtue, but he only defended the inalienability of virtue with reservations.

Middle and Neoplatonism

In the epoch of Hellenism and in the Roman Empire , the main topic of controversial discussions about the doctrine of virtue was the question of whether eudaimonia results solely from the arete or also requires external goods. Middle Platonists and Stoics professed the traditional principle of their schools that only virtue was required, while Peripatetics clung to Aristotle's teaching that external goods are also relevant. The influential Middle Platonist Attikos defended the Platonic doctrine with sharpness; he polemicized against the peripatetic view that eudaimonia also depends on noble origins, physical beauty and wealth. In this he saw a low and misguided thinking. The peripatetic Kritolaos advocated a compromise solution, according to which external goods are not entirely irrelevant, but of very little importance.

Plotinus , the founder of Neoplatonism , undertook a subdivision into higher and lower virtues, following on from Plato's ideas. The lower (“political”, civic) virtues are the traditional four basic virtues. You have to regulate the relationship of the soul to the body as well as to the environment. On the one hand, they determine social action; on the other hand, the goodness of the person composed of body and soul is based on them, because they ensure that the soul can exercise its leading function and the affects are restrained. In addition, Plotinus adopted four analogous higher virtues, which he named just like the lower ones (wisdom, prudence, bravery, justice), but which in his system have other, purely inner-soul functions. They free the soul from any disturbing influence by affects, physical factors and external circumstances and thus help it to become self-sufficient. In this way they give her an unshakable eudaimonia that cannot be influenced by external circumstances. They enable her to detach herself from the material world and to turn to a purely spiritual, divine area, the intelligible world. In the intelligible world, the true home of souls, there are no virtues because the divine does not need them because of its perfection. But as long as souls are still in the physical world and strive back to the divine, from which they once turned away, they need the virtues.

Later Neoplatonists ( Porphyrios , Iamblichus ) expanded the system by introducing further classes of virtue and arranging them hierarchically. In his work “Sentences that lead to the intelligible”, Porphyrios distinguished four classes of virtues: political (social) virtues as the lowest class, cathartic (cleansing), theoretical and paradigmatic (archetypal) virtues above them. He stated that the social virtues were a necessary preliminary stage for the attainment of the virtues of the three higher classes required for the soul's turning to the divine. Iamblichos added three classes, adding seven classes. As the lowest class he adopted natural virtues that animals naturally have (for example the bravery of the lion), as the second class "ethical" virtues (virtues of habit) that children and some animals can acquire through habituation without insight is available. The political (social), cathartic, theoretical and paradigmatic virtues follow in his scheme. In addition, Iamblichus introduced the class of theurgic virtues. Hierocles of Alexandria and Damascius emphasized the great value of political virtues in strengthening the soul.

Christianity

In the New Testament the term arete occurs only four times; two of these passages speak of human virtue. These are incidental mentions; details of what is meant by “virtue” are missing. The Apostle Paul writes in Philippians that one should be mindful of the virtues. In “the second letter of Peter ” the author, who poses as the apostle Peter , calls for people to show virtue in faith and knowledge in virtue.

The ancient church fathers took up the philosophical scheme of the four basic virtues. In doing so, they created the basis for its broad reception in the Middle Ages and for the paramount importance of the cardinal virtues in modern ethics. However, the medieval ideas of virtue were based on the mixing of the teachings of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers with Christian ideas, the dominant role of which led to a reshaping of the concept of virtue in essential aspects. The ancient arete was just one of the various roots of the medieval and early modern concepts of virtue.

literature

General

- Arthur WH Adkins: Merit and Responsibility. A Study in Greek Values . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1960.

- Peter Stemmer : Virtue. I. Antiquity . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 10, Schwabe, Basel 1998, Sp. 1532–1548.

Non-philosophical use of the term

- Werner Jaeger : Tyrtaios about the true ΑΡΕΤΗ . In: Werner Jaeger: Scripta minora , Volume 2, Edizioni di storia e letteratura, Rome 1960, pp. 75–114.

- Thomas Michna: ἀρετή in the mythological epic. An investigation of the history of meaning and genre from Homer to Nonnos . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-631-46982-9 .

- Harald Patzer : The archaic Areté canon in the Corpus Theognideum . In: Gebhard Kurz et al. (Ed.): Gnomosyne. Human thought and action in early Greek literature . Beck, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-406-08137-1 , pp. 197-226.

- Eva-Maria Voigt : ἀρετή . In: Lexicon of the early Greek epic , Volume 1, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1979, Sp. 1229–1232 (compilation of the evidence).

Philosophical discourse

- Marcel van Ackeren : Knowledge of the good. Significance and continuity of virtuous knowledge in Plato's dialogues . Grüner, Amsterdam 2003, ISBN 90-6032-368-8 .

- Dirk Cürsgen: virtue / best form / excellence (aretê) . In: Christian Schäfer (Ed.): Platon-Lexikon. Term dictionary on Plato and the Platonic tradition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-534-17434-8 , pp. 285-290.

- Hans Joachim Krämer : Arete with Plato and Aristotle. On the nature and history of the Platonic ontology . Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1959.

- Iakovos Vasiliou: Aiming at Virtue in Plato . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-86296-7 .

Remarks

- ↑ Eduardo Luigi De Stefani (ed.): Etymologicum Gudianum quod vocatur , Leipzig 1920, p. 190.

- ↑ Karl Kerényi : The myth of the areté . In: Karl Kerényi: Antike Religion , Munich 1971, pp. 240–249, here: 244; Werner Jaeger : Paideia , Berlin 1973, p. 26 note 3.

- ^ Pierre Chantraine : Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque. Histoire des mots , Paris 2009, p. 103; Hjalmar Frisk : Greek etymological dictionary , Volume 1, Heidelberg 1960, p. 136; Eduard Schwyzer : Greek Grammar , Volume 1, 5th Edition, Munich 1977, p. 501.

- ↑ References in Henry George Liddell , Robert Scott : A Greek-English Lexicon , 9th edition, Oxford 1996, p. 4, 237. Cf. Pierre Chantraine: Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque. Histoire des mots , Paris 2009, p. 6, 106 f.

- ↑ Arete of the horse in Homer, Iliad 23, 276; 23, 374.

- ↑ Werner Jaeger: Paideia , Berlin 1973, pp. 26–28, 41. For the Homeric Arete ideal, see also Arthur WH Adkins: Merit and Responsibility , Oxford 1960, pp. 34–40, 70 f .; Thomas Michna: ἀρετή in the mythological epic , Frankfurt am Main 1994, pp. 19–82.

- ↑ Homer, Ilias 9, 498. See Arthur WH Adkins: Merit and Responsibility , Oxford 1960, pp. 63 f.

- ^ Arthur WH Adkins: Merit and Responsibility , Oxford 1960, p. 36 f.

- ↑ On the problem of translating the term, see Peter Stemmer: Tugend. I. Antiquity . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 10, Basel 1998, Sp. 1532–1548, here: 1532 f.

- ↑ Hesiod, Werke and Tage 289 and 313. Cf. Hermann Fränkel : Poetry and Philosophy of Early Hellenism , Munich 1969, pp. 136, 614; Arthur WH Adkins: Merit and Responsibility , Oxford 1960, pp. 71-73; Thomas Michna: ἀρετή in the mythological epic , Frankfurt am Main 1994, pp. 91-107.

- ↑ On Tyrtaios' idea of Arete see Werner Jaeger: Paideia , Berlin 1973, pp. 125–137; Werner Jaeger: Tyrtaios about the true ΑΡΕΤΗ . In: Werner Jaeger: Scripta minora , Volume 2, Rome 1960, pp. 75–114, here: 88–99; Karl Kerényi: The myth of the areté . In: Karl Kerényi: Antike Religion , Munich 1971, pp. 240–249, here: 245.

- ↑ Georgios Karageorgos: The Arete as an educational ideal in the poems of Theognis , Frankfurt am Main 1979, p. 98 f.

- ↑ Georgios Karageorgos: The Arete as an educational ideal in the poems of Theognis , Frankfurt am Main 1979, pp. 76–156; Lena Hatzichronoglou: Theognis and Arete . In: Arthur WH Adkins et al. (Eds.): Human Virtue and Human Excellence , New York 1991, pp. 17-44; Harald Patzer: The archaic Areté canon in the Corpus Theognideum . In: Gebhard Kurz et al. (Ed.): Gnomosyne. Human thought and action in early Greek literature , Munich 1981, pp. 197–226, here: 213–215.

- ^ Pindar, Second Olympic Ode 53; Ninth Olympic Ode 101; Tenth Olympic Ode 20; Eleventh Olympic Ode 6; Third Isthmian Ode 4; Seventh Isthmian Ode 22. Cf. Hermann Fränkel: Poetry and Philosophy of Early Hellenism , Munich 1969, p. 557.

- ↑ Simonides, F 260 Poltera (= 542 Poetae melici Graeci), ed. by Orlando Poltera: Simonides lyricus. Testimonia and Fragmente , Basel 2008, pp. 203–209, 454–467 (critical edition with translation and commentary). Cf. Hermann Fränkel: Poetry and Philosophy of Early Hellenism , Munich 1969, pp. 352 f., 614.

- ↑ Lynette Mitchell: The Heroic Rulers of Archaic and Classical Greece , London 2013, pp. 57-80.

- ↑ Antiopi Argyriou-Casmeridis: Aretē in a Religious Context: Eusebeia and Other Virtues in Hellenistic Honorific Decrees. In: Elias Koulakiotis, Charlotte Dunn (ed.): Political Religions in the Greco-Roman World , Newcastle upon Tyne 2019, pp. 272–305, here: 273–276, 296 f.

- ↑ At Arete in the visual arts, see Jean-Charles Balty : Arete I . In: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC), Volume 2/1, Zurich 1984, p. 581 f. (Text) and Volume 2/2, Zurich 1984, p. 425 f. (Images) and addendum to the 2009 supplement of the LIMC, Düsseldorf 2009, volume 1, p. 85 (text) and volume 2, p. 196 (illustration); Cecil Maurice Bowra : Aristotle's Hymn to Virtue . In: The Classical Quarterly 32, 1938, pp. 182-189, here: 187 f.

- ↑ On this Arete concept see George B. Kerferd, Hellmut Flashar : Die Sophistik . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Sophistik, Sokrates, Sokratik, Mathematik, Medizin ( Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1), Basel 1998, pp. 1–137, here: 12 f. ; Jörg Kube: ΤΕΧΝΗ and ΑΡΕΤΗ. Sophistic and Platonic Tugendwissen , Berlin 1969, pp. 48–69.

- ↑ Jörg Kube: ΤΕΧΝΗ and ΑΡΕΤΗ. Sophistisches und Platonisches Tugendwissen , Berlin 1969, pp. 55–57.

- ↑ Peter Stemmer: Virtue. I. Antiquity . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 10, Basel 1998, Sp. 1532–1548, here: 1533; Friedemann Buddensiek : Eudaimonia . In: Christian Schäfer (Ed.): Platon-Lexikon , Darmstadt 2007, pp. 116–120.

- ↑ Louis-André Dorion provides an overview of the history of research: The Rise and Fall of the Socratic Problem . In: Donald R. Morrison (ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Socrates , Cambridge 2011, pp. 1–23.

- ^ Plato, Apology of Socrates 36c.

- ↑ Klaus Döring : Socrates, the Socratics and the traditions they founded . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Sophistik, Sokrates, Sokratik, Mathematik, Medizin ( Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1), Basel 1998, pp. 139–364, here: 157–159 .

- ↑ Terence Irwin: Plato's Ethics , New York 1995, pp. 55-60, 73-75.

- ^ Terence Irwin: Plato's Ethics , New York 1995, pp. 140 f.

- ^ Plato, Protagoras 319a-320c.

- ↑ See also Lynn Huestegge: Lust and Arete in Platon , Zurich 2004, pp. 21-25.

- ↑ Plato, Meno 71b – c.

- ↑ Klaus Döring: Socrates, the Socratics and the traditions they founded . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Sophistik, Sokrates, Sokratik, Mathematik, Medizin ( Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1), Basel 1998, pp. 139–364, here: 159 f. , 164.

- ↑ Patricia Ward Scaltsas: Virtue without Gender in Socrates . In: Konstantinos J. Boudouris (ed.): The Philosophy of Socrates , Athens 1991, pp. 408-415.

- ↑ Dirk Cürsgen: Virtue / Best Form / Excellence (aretê) . In: Christian Schäfer (Ed.): Platon-Lexikon , Darmstadt 2007, pp. 285–290, here: 286; Terence Irwin: Plato's Ethics , New York 1995, pp. 229-237.

- ↑ Dirk Cürsgen: Virtue / Best Form / Excellence (aretê) . In: Christian Schäfer (Ed.): Platon-Lexikon , Darmstadt 2007, pp. 285–290, here: 286.

- ↑ Plato, Politeia 591c-592a; see. Euthydemos 281d-e. On a softening of the position of the Platonic Socrates that only virtue is relevant for eudaimonia, see Gregory Vlastos : Socrates, Ironist and Moral Philosopher , Cambridge 1991, pp. 200–232; see. on this the criticism by Marcel van Ackeren: Das Wissen vom Guten , Amsterdam 2003, pp. 48–52. See also Terence Irwin: Plato's Ethics , New York 1995, pp. 118-120, 345-347.

- ↑ Michael Erler : Platon (= Hellmut Flashar (Hrsg.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/2), Basel 2007, p. 434 f.

- ↑ On the role of justice see Hans Joachim Krämer: Arete bei Platon und Aristoteles , Heidelberg 1959, pp. 85–96, 117 f.

- ↑ Christoph Horn et al. (Ed.): Platon-Handbuch , Stuttgart 2009, pp. 145–147, 196.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 309a-310a.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon (= Hellmut Flashar (Hrsg.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/2), Basel 2007, p. 438 f .; Charles H. Kahn: Plato on the Unity of the Virtues . In: William Henry Werkmeister (ed.): Facets of Plato's Philosophy , Assen 1976, pp. 21–39; Terry Penner: The Unity of Virtue . In: Hugh H. Benson (ed.): Essays on the Philosophy of Socrates , New York 1992, pp. 162-184 (advocating strong identity); Bruno Centrone: Platonic Virtue as a Holon: from the Laws to the Protagoras . In: Maurizio Migliori u. a. (Ed.): Plato Ethicus. Philosophy is Life , Sankt Augustin 2004, pp. 93-106; Michael T. Ferejohn: Socratic Thought-Experiments and the Unity of Virtue Paradox . In: Phronesis 29, 1984, pp. 105-122.

- ↑ Iakovos Vasiliou: Aiming at Virtue in Plato , Cambridge 2008, pp. 268-272, 283.

- ↑ Plato, Symposium 211d-212a.

- ↑ Plato, Theaetetus 176a – c.

- ↑ See on the connection between ideas and virtue Marcel van Ackeren: Das Wissen vom Guten , Amsterdam 2003, pp. 159–165, 179–183, 193 f., 205 f.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 6: 10-12.

- ↑ On the Arete concept of Antisthenes see Klaus Döring: Antisthenes, Diogenes and the Cynics of the time before the birth of Christ . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Sophistik, Sokrates, Sokratik, Mathematik, Medizin ( Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1), Basel 1998, pp. 267–364, here: 275–278 .

- ↑ Peter Stemmer: Virtue. I. Antiquity . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 10, Basel 1998, Sp. 1532–1548, here: 1538; Philipp Brüllmann: Luck. In: Christof Rapp , Klaus Corcilius (ed.): Aristoteles-Handbuch , Stuttgart 2011, pp. 232-238, here: 233 f.

- ↑ See on this doctrine of virtue Peter Stemmer: Virtue. I. Antiquity . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 10, Basel 1998, Sp. 1532–1548, here: 1538. On the question of whether it is innate predispositions or acquired attitudes, see Aristoteles, Nikomachische Ethik 1105b – 1106a.

- ↑ Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 1106a – 1109b. On the role of cleverness, see Arthur WH Adkins: Merit and Responsibility , Oxford 1960, pp. 332-335.

- ↑ Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 1177a – b; see. 1097b-1098a. See Arthur WH Adkins: Merit and Responsibility , Oxford 1960, p. 344 f.

- ↑ Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 1178a – b. See Arthur WH Adkins: Merit and Responsibility , Oxford 1960, pp. 345-348.

- ↑ Peter Stemmer: Virtue. I. Antiquity . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 10, Basel 1998, Sp. 1532–1548, here: 1540, 1543; Philipp Brüllmann: Luck. In: Christof Rapp, Klaus Corcilius (eds.): Aristoteles-Handbuch , Stuttgart 2011, pp. 232–238, here: 234.

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics 1260a.

- ↑ Werner Jaeger: Aristoteles , 3rd edition, Dublin and Zurich 1967, pp. 117–120 (p. 118 text of the hymn); Karl Kerényi: The myth of the areté . In: Karl Kerényi: Antike Religion , Munich 1971, pp. 240–249, here: 246–249 (p. 246 f. Translation of the hymn); Cecil Maurice Bowra: Aristotle's Hymn to Virtue . In: The Classical Quarterly 32, 1938, pp. 182-189.

- ↑ Katharina Held : Hēdonē and Ataraxia near Epikur , Paderborn 2007, p. 40 f .; Michael Erler: Epicurus . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): The Hellenistic Philosophy ( Outline of the History of Philosophy. The Philosophy of Antiquity , Volume 4/1), Basel 1994, pp. 29–202, here: 159.

- ↑ Peter Stemmer: Virtue. I. Antiquity . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 10, Basel 1998, Sp. 1532–1548, here: 1541.

- ↑ Peter Steinmetz : The Stoa . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): The Hellenistic Philosophy ( Outline of the History of Philosophy. The Philosophy of Antiquity , Volume 4/2), Basel 1994, pp. 491–716, here: 526 f., 542 f., 616 f.

- ↑ Not all of them; Youre Song names two exceptions ( Plutarch , Lukios Kalbenos Tauros ): Ascent and Descent of the Soul , Göttingen 2009, p. 82.

- ↑ Peter Stemmer: Virtue. I. Antiquity . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 10, Basel 1998, Sp. 1532–1548, here: 1542–1544.

- ↑ Plotinus, Enneads I 2,1,15-27.

- ↑ Plotinus enneads I 2,3,31 f. On Plotin's doctrine of virtue, see Euree Song: Ascent and Descent of the Soul , Göttingen 2009, pp. 24–28, 44–52, 77–90.

- ↑ Dominic J. O'Meara: Platonopolis , Oxford 2003, pp. 44-46.

- ↑ Dominic J. O'Meara: Platonopolis , Oxford 2003, pp. 46-49.

- ↑ Philippians 4.8 EU .

- ↑ 2 Peter 1,5 EU .

- ↑ See on the reception by the Church Fathers and on the medieval developments István P. Bejczy: The Cardinal Virtues in the Middle Ages , Leiden / Boston 2011, pp. 11 f., 28–47, 65–67, 132 f., 218– 221, 285-289.