Atlantic electric ray

| Atlantic electric ray | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Atlantic electric ray ( Tetronarce nobiliana ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Tetronarce nobiliana | ||||||||||||

| ( Bonaparte , 1835) |

The Atlantic torpedo ( Tetronarce nobiliana , Syn. : Torpedo nobiliana ) with a body length of up to 1.80 meters and weighing 90 kilograms, the largest species in the family of the torpedo . It lives at depths of up to 800 meters mostly over sandy or muddy ground off the coasts of the western and eastern Atlantic and in the Mediterranean . Younger individuals usually live close to the ground in shallower sea areas, while the adult animals prefer a pelagic way of life and can therefore be found in open water.

Like all rays , it is strongly flattened and has greatly enlarged pectoral fins. At night it hunts small fish and crustaceans that live close to the ground, which it stuns or kills electrically with a voltage of up to 220 volts . He also uses electric shocks against potential threats, although these are only very rarely life-threatening for humans.

features

With a body length of up to 1.80 meters and a weight of 90 kilograms, the Atlantic electric ray is the largest known type of electric ray. Body lengths of 0.6 to 1.5 meters and a weight of around 15 kilograms, however, are more in line with the average. The females become larger than the males. The upper side is a single color dark to blue-gray or dark brown, the underside white. It does not have the typical spots and thorns on its back that are typical of the family, but individual indistinct spots and darker fin edges can appear.

The ray has the typical somewhat wider than long disc shape of its family, whereby the almost round body disc formed by the greatly enlarged pectoral fins is about 1.2 times as wide as it is long. The front edge of the body is almost straight and thickened by an overlap of the pectoral fins. The eyes are small, behind them are the significantly larger injection holes with a smooth inner edge. The nostrils are close to the mouth opening, between them there is a flap of skin that is three times as wide as it is long and has a curved rear edge. The mouth opening is wide and angled and has clearly pronounced pits in the corners of the mouth. The teeth are pointed and increase in number over the course of life, with young rays having 38 and adult rays up to 66 rows of teeth. The five pairs of gill slits are small, with the first and fifth pairs being shorter than the middle pairs. As with all rays, they lie on their belly side.

Two dorsal fins, of which the front is two to three times larger than the rear, are located near the base of the tail at a distance that is less than the length of the first fin. The first dorsal fin is triangular with a rounded tip. The relatively short, unusually strong and thick tail makes up about a third of the body length and ends in a caudal fin in the shape of an isosceles triangle with slightly convex fin edges. Unlike most other rays, electric rays do not swim with their pectoral fins, but rather, like sharks, by moving their tail sideways. The skin is soft and has no dander.

distribution and habitat

The Atlantic electric ray is widespread in cool to moderately cold waters on both the American, European and African Atlantic coasts . In the eastern Atlantic it can be found from northern Scotland over the entire European Atlantic coast and the Mediterranean to the Gulf of Guinea as well as from Namibia to South Africa and in the area of the Azores and Madeira . In the western Atlantic, the distribution area extends from Nova Scotia , Canada , to the coasts of Venezuela and Brazil in South America. It is classified as rare in the North Sea , the Mediterranean Sea, and south of North Carolina .

Young electric rays mainly live benthically , i.e. on the sea floor, and can be found mainly in shallow water areas at depths of 10 to 50 meters, occasionally significantly deeper, over sandy to muddy ground or in the vicinity of coral reefs . In the course of development and after reaching sexual maturity , they sometimes become pelagic and accordingly stay in higher water areas. Adult electric rays are often found in the open water of the offshore sea areas. According to this way of life, the ray is found in the area from the water surface to depths of up to 800 meters, in the Mediterranean the preferred depth is documented at 200 to 500 meters. The Atlantic electric ray is believed to travel long distances as a migratory fish .

Way of life

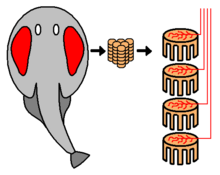

Like other electric rays, the Atlantic electric ray is capable of generating a powerful electric shock for both prey and defense . This is produced by a pair of kidney-shaped electrical organs located in the body disc. They represent about one sixth of the body weight of the rays and consist of about half a million slime-filled electrical plates, which are arranged in more than 1000 vertical and hexagonal columns visible under the skin. The pillars work in the same way as electrical batteries connected in parallel , whereby a rested Atlantic electric ray can produce an electrical output of up to one kilowatt at 170–220 volts . The electrical discharge takes place in a series of pulses in rapid succession, each lasting about 0.03 seconds. A series contains an average of 12 impulses, although series of more than 100 impulses have also been documented. The ray also sends out regular impulses without an obvious external stimulus.

The Atlantic electric ray is a solitary animal that stays on or halfway under the seabed substrate during the day and becomes active at night. Some observations suggest that this ray can survive out of the water for up to a day.

nutrition

The Atlantic electric ray feeds primarily on smaller bony fish , including flatfish , salmon fish , mullets and eels . It also preyed on small cat sharks and crustaceans . In the case of electric rays kept in captivity, it has been observed that they usually lie still on the ground when catching prey and "pounce" from this position on passing prey fish. At the moment of contact, the ray clamps the prey against its body or the sea floor by flapping its large pectoral fins around it and at the same time giving it electrical impulses with the help of electrical organs. In this way, it is possible for even the slow animal to capture animals that swim comparatively quickly. The overwhelmed prey is then carried to the mouth by undulating movements of the pectoral fins and swallowed whole head first. The very flexible jaws allow the electric ray to grab large prey and swallow it. For example, a whole salmon weighing 2 kilograms was found in the stomach of one individual, while another had swallowed a 37 centimeter long flatfish of the Paralichthys dentatus species . This ray is also known to kill fish that are much larger than it could eat.

Predators and parasites

Due to its size and ability to defend itself, the rays rarely prey on other animals. The known parasites of the ray include the tapeworms Calyptrobothrium occidentale and C. minus , Grillotia microthrix , Monorygma sp. and Phyllobothrium gracile and the monogenean belonging Amphibdella flabolineata and Amphibdelloides maccallumi and the copepod Eudactylina rachelae .

Reproduction and development

The Atlantic electric ray is viviparous, whereby the dams do not form a placenta (aplacental viviparous ). During the initial phase of their development, the embryos feed on the yolk contained in the egg cell , which after consumption is replaced by a protein and fat-rich cell fluid produced by the mother ("uterine milk"). The females have two functional ovaries (ovaries) and uteri (uteri). Their reproductive cycle is likely to be two years.

After a gestation period of about a year, the females give birth to up to 60 young rays in summer, with the litter size increasing with the size of the mother. With a length of about 14 centimeters, the embryo has a pair of nodes on the front of the body disc, which mark the origin of the pectoral fins, and the membranous separation of the nostrils is not yet present, on the other hand, the eyes, the injection hole, the gills, the dorsal fins and the caudal fin already attains the proportions of the full-grown ray at this stage. Newborn electric rays are 17 to 25 centimeters in length and still have the knots on the front edge of the body. With a length of about 55 to 90 centimeters, both males and females reach sexual maturity .

Evolution and systematics

The first scientific description of the Atlantic electric ray was made in 1835 by the French naturalist Charles Lucien Bonaparte in his presentation of the fauna of Italy under the title Iconografia della Fauna Italica . 16 individuals of the electric ray were used as syntypes to describe the species.

The Atlantic electric ray was assigned to the genus Torpedo , which belongs to the electric ray family (Torpedinidae). Within this, the Atlantic electric ray was assigned to the sub-genus Tetronarce , which differs from the other sub-genera primarily through its uniform coloration and the smooth-edged spray holes . Tetronarce has recently been listed as an independent genus, so that Tetronarce nobiliana is now the valid scientific name for the species.

The assignment of the South African big electric ray to this species is controversial and is considered provisional, and evidence of a electric ray in the Indian Ocean off Mozambique could also belong to this species.

Relationship with people

The electric shocks generated by the Atlantic electric ray are very rarely life-threatening to a person, but they are very strong and can lead to unconsciousness . For a diver, however, the disorientation that follows such an electric shock is the greatest danger.

Cultural history and use

Historically, electric fish, including the Atlantic electric ray, were used for medicinal purposes in ancient times . The Roman physician Scribonius Largus described in his compositions in the first century of our era the use of live "dark electric rays" in patients with gout or chronic headaches .

Around 1800 the electric ray, called torpedo in English-speaking countries , gave its name to the bombs called torpedo by the American inventor Robert Fulton in the form of a towed gunpowder charge that a submarine (in his case the " Nautilus ") could use against ships (and which at that time corresponded more to today's sea mines ).

Before the introduction of petroleum- based fuels , the liver oil of this species was regarded as qualitatively equivalent to that of the sperm whale ( Physeter macrocephalus ) and was used as lamp oil . It was also used by seafarers as a remedy for muscle and stomach cramps until the 1950s , and it was also used as a lubricant for agricultural implements.

Together with other types of electric rays, the Atlantic electric ray also serves as a model organism in biomedical research, since the electrical organs have numerous receptor proteins for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine . These receptors play a central role in the control of neural processes and are important, among other things, in the field of anesthesia .

Fisheries and endangerment

Electric rays are often caught as bycatch in bottom trawling and longline fisheries, but there is no commercial use due to the very limp and tasteless meat. When caught at sea, it is usually discarded or cut up as bait. It is considered potentially endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, very little data are available for assessment, which is why it is shown in the Red List of Threatened Species as a species for which insufficient data on capture rates and population developments are available for risk assessment ( data deficient ). Bycatch and the destruction and damage of spawning grounds in shallow water areas, which are important for development, by trawling, can become precarious for the species. Its slow rate of reproduction limits the capacity to recover from population decline.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Burton, R .: International Wildlife Encyclopedia , third. Edition, Marshall Cavendish, 2002, ISBN 0761472665 , p. 768.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bigelow, HB and WC Schroeder: Fishes of the Western North Atlantic, Part 2 . Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University, 1953, pp. 80-104.

- ↑ a b c d Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Atlantic Torpedo . Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d Capapé, C., O. Guélorget, Y. Vergne, JP Quignard, MM Ben Amor and MN Bradai: Biological observations on the black torpedo, Torpedo nobiliana Bonaparte 1835 Chondrichthyes: Torpedinidae, from two Mediterranean areas Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Annales Series Historia Naturalis Koper . 16, No. 1, 2006, pp. 19-28.

- ↑ Kurt Fiedler: Textbook of Special Zoology, Volume II, Part 2: Fish . Page 234, Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena, 1991, ISBN 3-334-00339-6

- ^ Eschmeyer, Herald, Hamann: Pacific Coast Fishes , p. 53, Peterson Field Guides, ISBN 0-395-33188-9

- ↑ a b c d e f Tetronarce nobiliana in the Red List of Endangered Species of the IUCN 2009. Posted by: Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Serena, F., Ungaro, N., Ferretti, F., Holtzhausen, HA & Smale, MJ, 2004. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ↑ Langstroth, L. and T. Newberry: A Living Bay: the Underwater World of Monterey Bay . University of California Press, 2000, ISBN 0520221494 , p. 222.

- ^ Lythgoe, J. and G. Lythgoe: Fishes of the Sea: The North Atlantic and Mediterranean . Blandford Press, 1991, ISBN 026212162X , p. 32.

- ↑ a b Day, F .: The Fishes of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 2 . Williams and Norgate, 1884, pp. 331-332.

- ↑ a b Michael, SW: Reef Sharks & Rays of the World . Sea Challengers, 1993, ISBN 0930118189 , p. 77.

- ^ A b Wilson, DP: Notes From the Plymouth Aquarium II . In: Journal of the Biological Association of the United Kingdom . 32, No. 1, 1953, pp. 199-208. doi : 10.1017 / S0025315400011516 .

- ↑ Tazerouti, F., L. Euzet and N. Kechemir-Issad: Redescription of three species of Calyptrobothrium monticelli , 1893 (Tetraphyllidea: Phyllobothriidae) parasites of Torpedo marmorata and T. nobiliana (Elasmobranchii: Torpedinidae). Remarks on their parasitic specificity and on the taxonomical position of the species previously attributed to C-riggii Monticelli, 1893 Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Systematic Parasitology . 67, No. 3, July 2007, pp. 175-185. doi : 10.1007 / s11230-006-9088-9 . PMID 17516135 .

- ↑ Dollfus, RP: De quelques cestodes tetrarhynques (Heteracantes et Pecilacanthes) recoltes chez des poissons de la Mediterranee . In: Vie Milieu . 20, 1969, pp. 491-542.

- ↑ Sproston, NG: On the genus Dinobothrium van Beneden (Cestoda), with a description of two new species from sharks, and a note on Monorygma sp. from the electric ray . In: Parasitology Cambridge . 89, No. 1-2, 1948, pp. 73-90.

- ↑ Williams, HH: The taxonomy, ecology and host-specificity of some Phyllobothriidae (Cestoda: Tetraphyllidea), a critical revision of Phyllobothrium Beneden, 1849 and comments on some allied genera . In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society . 253, No. 786, 1968, pp. 231-301. doi : 10.1098 / rstb.1968.0002 .

- ↑ Llewellyn, J .: Amphibdellid (monogenean) parasites of electric rays (Torpedinidae) . In: Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom . 39, 1960, pp. 561-589. doi : 10.1017 / S0025315400013552 .

- ↑ Green, J .: Eudactylina rachelae n. Sp., A copepod parasitic on the electric ray, Torpedo nobiliana Bonaparte Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Information: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom . 37, 1958, pp. 113-116. doi : 10.1017 / S0025315400014867 .

- ↑ Eschmeyer, WN and R. Fricke, eds. nobiliana, torpedo . Catalog of Fishes electronic version (January 15, 2010).

- ^ Fowler, HW: Notes on batoid fishes . In: Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia . 62, No. 2, 1911, pp. 468-475.

- ↑ Tetronarce in the Catalog of Fishes (English)

- ^ Whitaker, H., C. Smith, S. Finger: Brain, Mind and Medicine: Essays in Eighteenth-Century Neuroscience . Springer, 2007, ISBN 0387709665 , pp. 126–127.

- ^ Adkins, L .: The War for All the Oceans: From Nelson at the Nile to Napoleon at Waterloo . Penguin Group, 2008, ISBN 0143113925 , p. 138.

- ↑ Fraser, DM, RW Sonia, LI Louro, KW Horvath and AW Miller: A study of the effect of general anesthetics on lipid-protein interactions in acetylcholine receptor-enriched membranes from Torpedo nobiliana using nitroxide spin-labels Archived from the original on 21. July 2011. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Biochemistry . 29, No. 11, 1990, pp. 2664-2669. doi : 10.1021 / bi00463a007 . PMID 2161253 .

Web links

- Atlantic electric ray on Fishbase.org (English)

- Tetronarce nobiliana inthe IUCN 2013 Red List of Threatened Species . Posted by: Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Serena, F., Ungaro, N., Ferretti, F., Holtzhausen, HA & Smale, MJ, 2004. Accessed November 2, 2013.

- Species portrait at the Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department

- Atlantic electric ray at habitas.org (English).

- Atlantic electric ray at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute .