Augsburger Strasse (Berlin)

| Augsburger Strasse | |

|---|---|

| Street in Berlin | |

| View over Augsburger Strasse at the level of Würzburger Strasse , in front of the Nürnberger Strasse intersection | |

| Basic data | |

| place | Berlin |

| District |

Schöneberg , Wilmersdorf , Charlottenburg |

| Created | March 11, 1887 |

| Newly designed | October 29, 1957 |

| Connecting roads |

Lietzenburger Strasse , Fuggerstrasse |

| Cross streets |

Joachimsthaler Strasse , Rankestrasse , Marburger Strasse , Nürnberger Strasse , Passauer Strasse |

| Places | Los Angeles Square |

| Buildings | Augsburger Strasse underground station |

| use | |

| User groups | Pedestrian traffic , bicycle traffic , car traffic |

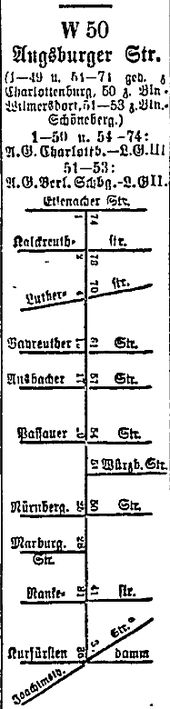

The Augsburger Strasse is centrally located in the City West location Berlin street, not to be confused with an eponymous street in Berlin-Lichtenrade . It was laid out in 1887 and at that time extended from Kurfürstendamm to Eisenacher Straße . After it was shortened in 1936 and then again in 1957, it now runs as a parallel street to Tauentzienstrasse only between Joachimsthaler and Passauer Strasse .

At the beginning of the 20th century it became part of the “ New West ”, in the Roaring Twenties there were numerous prominent localities there, and the street was part of a brief heyday of German art and culture. As a result of National Socialism , the street lost this importance. The buildings suffered severe damage in the Second World War . In the post-war period it was the site of a large street prostitute for decades . It was not until the 1980s that the last large vacant lots that had been torn by the war were closed again. Today Augsburger Strasse is a purely residential and commercial street, particularly characterized by several large upper-class hotels. The residents have on average a high income.

New construction of the road

Augsburger Straße was designated in 1862 in the first Berlin development plan, the Hobrecht Plan , as streets 29 and 30 of Section IV. It was laid out until 1887 and named after the Bavarian city of Augsburg on March 11th of that year . At the time it was built, the street was around 1,400 meters long, began at Kurfürstendamm and extended over Joachimsthaler Straße , Rankestraße , Marburger Straße , Nürnberger Straße , Passauer Straße , Ansbacher Straße , Welser Straße , Martin-Luther-Straße and Kalckreuthstraße to Eisenacher Straße .

For a short time Augsburger Strasse was on the outskirts. Moritz Goldstein , who lived here as a child for around two years shortly after the complex, described the character of the street at the time as a place “where the big city turned into open country [...] In ten minutes we could see the untouched nature with tilled cornfields, meadow grass and Reaching watercourses ". Goldstein captured both the economic and structural moment of growth in the district when he wrote of the residents, “Most of them did well and made progress as the area developed” and “We watched the city with pride and ardent participation grew around us. "

Temporarily there were still green spaces, a city map from 1893 shows a green space as a hippodrome at the corner of Joachimsthaler Straße . In these gaps, however, the new West was already being announced: On July 23, 1890, Buffalo Bill made a guest appearance "in a large, fenced-in, wood-covered park" at the confluence with Kurfürstendamm with his Wild West show of around two hundred Indians , cowboys and artists as well as two hundred animals . Art shooter Annie Oakley caused a sensation when Kaiser Wilhelm II lit a cigar, asked if she would shoot it out of his mouth and Oakley shot it out of his hand as soon as he had asked.

Augsburger Strasse in the "New West"

Augsburger Strasse quickly became part of the " New West " with its typical mix of upscale residential areas, business and entertainment districts. The Augsburger Strasse was also quickly developed in terms of traffic. From 1895 the yellow line of the Berlin-Charlottenburg tram ran through Augsburger Strasse. In 1900 the route was taken over by the Great Berlin Tram and electrified. The tracks lay in the section between Lutherstrasse and Kurfürstendamm, on Rankestrasse and Nürnberger Strasse they crossed other routes. On February 11, 1923, the street was used as scheduled by trams for the last time.

In addition to locally prominent people such as Charlottenburg's Lord Mayor Kurt Schustehrus (around 1906, Augsburger 62), personalities known as influential for modern times chose their center of life here at an early stage . As early as 1895, the architect August Menken lived for several years at Augsburger Strasse 50, near the Kurfürstendamm intersection, where his office was located . In the neighborhood at number 48, the young Arnold Schönberg lived in 1903 during his first short stay in Berlin . Above all, the centrally located guest houses in the “ New West ” offered cheap and long-term accommodation for artists and bohemians . From November 10, 1900, the Japanese writer Iwaya Sazanami lived in a room in “Augusuburuku machi” 21 for six months , and his Berlin diary documents Berlin at that time for its Japanese audience. Two houses next to Schönberg, at Augsburger Straße 46, lived the poet Victor Hadwiger in 1903. Johannes Nohl took over his room and moved in with his partner at the time, Erich Mühsam , who was already living there . In his memoirs, Mühsam described his furnished room as a “place of rich experiences and strong inner support for me”. Regular guests were John Henry Mackay , Johannes Schlaf and Hanns Heinz Ewers .

Even subjects from the visual arts can be found here: In 1911 the expressionist painter Ludwig Meidner painted his painting Gasometer in Berlin-Wilmersdorf . In it he held a 50 meter high gas container erected in 1895 in the eastern section of Augsburger Straße . The 81,000 cubic meter container was destroyed in World War II in 1944 and demolished in the early 1950s. In its place, at the corner of Fuggerstrasse and Welserstrasse, is the Finow elementary school today .

The Roaring Twenties

In the " Golden Twenties " Augsburger Straße was the axis between Kurfürstendamm and Motzstraßeviertel and offered space to renowned locations of the era in which demi-world and bohemian were mixed.

Presumably founded in the 1910s or earlier, the “ Kakadu ” bar on Augsburger Strasse at the corner of Kurfürstendamm became an important meeting place for artists, stars and business leaders. In 1920 the bar expanded and in the years to come claimed to be the “largest bar in Berlin”. The bar continued until the 1930s, then in 1937 the bar became a "wine tavern", and in 1938 even a confectionery. In 1943 the building was confiscated and converted into accommodation for the Reich Labor Service . Allied bombs destroyed it later so badly that it had to be demolished. Today the Allianz high-rise stands there .

Directly opposite, on the corner of Joachimsthaler Strasse, at Augsburger Strasse 36, was “ Maenz 'Bierhaus ”. The coachman's bar run by the landlady Änne Maenz and the legendary waiter Adalbert "Papa Duff" Duffner renounced the plush furnishings that were familiar at the time and became a meeting point for artists, especially for actors, directors and writers such as Ernst Lubitsch , Emil Jannings and Kurt from 1918 Pinthus , Ernst Rowohlt , Fritzi Massary , Bertolt Brecht , Conrad Veidt , Jakob Tiedtke , Emil Orlik , Stefan Großmann , Alexander Granach and many more. The author Alfred Richard Meyer dedicated his book Maenz or Maenzliches to the place in 1922 . All too many or the masculine comedy .

At the intersection with Lutherstrasse 21 (since 1963: Martin-Luther-Strasse 12) was the restaurant " Horcher " from 1904 to 1944 . On the square behind it, the “ Scala ”, one of the most famous variety theaters in Germany, was built in 1920 , which existed until the building was destroyed on the night of November 22nd to 23rd, 1943. Parts of the Scala building were provisionally used as a venue for the cabaret Die Wühlmäuse from 1960 . The building was later demolished and replaced by a no-nonsense residential building in the 1970s. Directly opposite the “Scala” was the “Auguste Victoria-Saal” and from 1926 to 1932 the “Original Eldorado ”.

The psychoanalysts Melanie Klein and Helene Deutsch , pupils of Karl Abraham, who lives at Rankestrasse 24, lived in a guesthouse at Augsburger Strasse 23 from 1921 to 1926 and from 1923 to 1924 respectively . In the “Roaring Twenties” contemporary artists also took up residence in the street. The painter Rudolf Schlichter had his studio here in the 1920s. After moving to Berlin in 1927, the painter Christian Schad lived in a guest house on Augsburger Strasse while he was looking for a studio. There was a hat shop on the first floor of the house, where he met a milliner who was the model for one of his most famous portraits: Lotte - The Berliner .

The homosexual Berlin that was so vital in the area and shaped the era was also reflected in Augsburger Strasse. From 1924 to 1933 the “Auluka-Diele” existed at Augsburger Straße 72, a lesbian pub that was later characterized as “next to it to the point of extravagance” in contrast to the very fashionable restaurants on the surrounding streets. In 1930 and 1932 the lesbian club "Geisha" can be found at the same address.

National Socialism and World War II

The actions of the National Socialists against the Berlin bohemians and the homosexual scene put an end to the " Roaring Twenties " also in cultural terms. In the time of National Socialism , Augsburger Strasse lost its character as part of a center of art and culture. Importance was the road at this time possibly even the seat of the 1933 founded and the Ministry of Economic Affairs subordinate monitoring point for rubber and asbestos .

The original mouth point on Kurfürstendamm has been operating as an independent Joachimsthaler Platz since 1936 . Since this cap of around 50 meters, the western Augsburger Strasse ends at Joachimsthaler Strasse and no longer flows directly into Kurfürstendamm.

Since 1939, the Holocaust has also hit the Jewish residents of Augsburger Strasse: Today, seven stumbling blocks remind of their fate. Among the victims was the theater scholar Max Herrmann , who lived and worked with his wife, the philologist Helene Herrmann , at Augsburger Strasse 42 until September 1942. Both were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp , where Max Hermann died within two months, Helene Herrmann survived until the summer of 1944 and was then murdered in Auschwitz .

As a street partly directly behind Kurfürstendamm and Tauentzienstrasse , Augsburger Strasse suffered severe damage during the war: the buildings in the area between Nürnberger Strasse and Ansbacher Strasse were almost completely destroyed at the end of the war, and the street between Ranke and Marburger Strasse, where only houses stood in the middle. In the eastern area the damage was somewhat less, but no street remained untouched. The large gas tank painted by Ludwig Meidner there was destroyed in 1944 and never rebuilt.

Augsburger Strasse in West Berlin

Street prostitution of the post-war period

While the former amusement street was still characterized by contemporary witnesses in its silence as "no running area" immediately after the war, an increasingly frequented street developed there in the following years . On the occasion of the currency reform in 1948, Der Spiegel reported on the "ladies of the [...] guild on Kurfürstendamm and in Augsburger Strasse", who were "generally twice as expensive" as those on Friedrichstrasse . A report from 1950 speaks of Augsburger Strasse as “Berlin's sinful street” and mentions a “private brothel”.

Prostitution in the street did not remain a phenomenon of the immediate post-war period , the corner of Augsburger and Joachimstaler Strasse temporarily became a symbol of prostitution in West Berlin . A DEFA film published at the end of 1959, which compares the two halves of Berlin for propaganda purposes, first shows the street signs on Augsburger and Joachimstaler Strasse, then prostitutes and underlines it with the comment "Here you can find everything, you can simply buy everything here [...]". In the mid-1960s, Augsburger was known as the “street that is notorious for its amorous offers”, and in 1965 there was talk of “a few hundred girls” in the Augsburger, Ranke- and Joachimstaler Strasse block. The call of the street was so explicit that Helen Vita and Edith Hancke celebrated it in a contemporary song with the words: "Joachimstaler Straße corner Augsburger Straße / there is a sharp wind blowing / long boots, short skirts / so they walk around the corner / Day and night, my beautiful child ”, to finally ask“ What's the matter with the corner? ”.

reconstruction

Red: the new south bypass (Lietzenburger Straße)

Yellow: historical course of Augsburger Straße (corner Joachimstaler Straße missing), marked east of the south bypass as a budding Fuggerstraße

Black hatched: denotes preserved buildings,

white filled outlines: ruins

Many of the war ruins stood well into the 1950s, only then did reconstruction begin. Some of the buildings that were still preserved gave way to new designs for the design of the city. This was noticeable in Augsburger Strasse between Ranke- and Marburger Strasse: a few houses were there until 1950. Then they were torn down and gave way to a parking lot for Ku'damm visitors.

A special urban planning decision was of particular importance for Augsburger Strasse: the eastern section behind the Passauer Strasse intersection was separated by the extension of Lietzenburger Strasse as part of the planned southern bypass and renamed Fuggerstrasse on October 29, 1957 . Since then, the greatly shortened Augsburger Strasse has only run as a southern parallel street to Tauentzienstrasse from Joachimsthaler to Passauer Strasse .

The division not only significantly shortened Augsburger Strasse, but also lost a particularly historic section. Today, Fuggerstrasse is part of the neighborhood around Nollendorfplatz , which, with its numerous gay pubs, clubs, shops and discos, ties in with the historical significance of the area.

The Augsburger Straße underground station was built from 1959 to 1961, and today it serves as a stop for the U3 line . According to the city's list of monuments, it is the only monument on the street today; Augsburger Straße has no monuments above ground.

On March 21, 1967, the Hotel Alsterhof Berlin was opened at the eastern end of Augsburger Strasse . The old house was replaced by a new, seven-story building in 1997 and has been a 4-star hotel ever since . In 2014, the hotel was taken over by the Scandic Hotels chain and has been operating as Scandic Berlin Kurfürstendamm ever since .

The vacant lot between Ranke- and Marburger Strasse, which had existed for a long time as a parking lot since the Second World War and the ruins were torn down in the 1950s, was closed on November 29, 1982 by adding Los-Angeles-Platz . Parking space has since offered an underground car park below. It is the only publicly accessible green space between the Großer Tiergarten and the University of the Arts , but was sold to the parking garage operator Contipark on January 1, 1997.

Augsburger Strasse at the turn of the millennium

Augsburger Strasse is now a pure hotel, residential and commercial street, around 620 meters long and a little over 26 meters wide. The zoning plan shows the adjacent land west of Nürnberger Straße as mixed construction area, to the east of it as residential construction area. In the corresponding development plans, the street area is largely designated as a mixed area , only west of Rankestrasse as the core area.

At the turn of the millennium, Augsburger Strasse was not unaffected by the fact that “City West” redefined its role in the context of the city as a whole after German reunification . The corner of Joachimstaler Strasse, with its close proximity to Kurfürstendamm, was particularly hard hit.

The Ku'damm-Eck made the start. The existing building with its architecture in the style of the 1970s was torn down in 1998, and the new Ku'damm-Eck took its place . The ten-storey and 45-meter-high building with a 70 m² video screen on the facade and a prominently placed sculpture ensemble by Markus Lüpertz was opened in 2001. The building erected by the architects Gerkan, Marg und Partner houses a branch of the department store chain C&A on the Kurfürstendamm side , while the entrance to the Swissôtel Berlin , a five-star hotel , is on Augsburger Straße .

After the opening of the new Ku'damm-Eck, construction began on the opposite corner of Augsburger and Joachimstaler Strasse. The C&A department store previously located there, which had become vacant when C&A moved into the Ku'damm-Eck, was demolished in 2002. The Hotel Concorde Berlin was built in its place by October 2005, also a five-star hotel with eye-catching architecture. The over 60 meter high building designed by the architect Jan Kleihues has received several awards and has been known as Sofitel Berlin Kurfürstendamm since 2014 .

The other commercial residents of the street are mostly smaller retailers, office service providers and restaurateurs. The residential development consists mostly of old apartments opposite Los-Angeles-Platz and new buildings at the eastern end of the street. A relatively large number of people live here in a social housing complex built between 1986 and 1988, which extends to Passauer Strasse and has 156 tenants. The discontinuation of rent subsidies by the Senate led to the housing company degewo doubling or tripling the rent in 2003 . Protests by the tenants remained in vain, and around a quarter of the residents had to quit their apartment and move out.

Economically, the residents of Augsburger Strasse were relatively well off at the beginning of the 2000s: for 2005 there are figures on purchasing power per capita, according to which each resident had a purchasing power of 20,643 euros. This value was well above the Berlin average of 16,700 euros, but also remained clearly below the Charlottenburg-Wilmerdorfer average of 22,289 euros.

Web links

proof

- ↑ a b Augsburger Strasse. In: Street name dictionary of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (near Kaupert ), accessed on December 23, 2012.

- ↑ a b c Measurement using Google Maps with Maps Labs rangefinder , accessed on February 23, 2013

- ↑ a b Julius Straub (Ed.): Plan von Berlin , supplement to the Berlin address book 1893, 1893, alt-berlin.info ( memento of the original from January 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed February 10, 2013

- ↑ Joachim Schlör: The I of the city. Debates on Judaism and Urbanity, 1822–1938 , 2005, ISBN 978-3-525-56990-0 , pp. 71–72

- ^ Berlin calendar . In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 7, 1999, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 120–127 ( luise-berlin.de - p. 126, 1890 in the Widwestshow…).

- ↑ tagesspiegel.de: 125 years of Ku'damm (1): Play me the song from Ku'damm - City Life - Berlin - Tagesspiegel, accessed on December 29, 2012

- ↑ berlin.bahninfo.de: Bahninfo Regional - Berlin / Brandenburg , accessed on December 16, 2013

- ^ H. Bombe: Berlin Horse Railway 1865-1894 - Berlin-Charlottenburg Tram 1894-1919 . In: Der Berliner Verkehrsamateur , 8/1955, p. 3

- ↑ berliner-bahnen.de: Berlin-Charlottenburger-Straßenbahn - Chronicle - Railways in the Berlin area - Tram , accessed on February 10, 2013

- ↑ berliner-bahnen.de: Great Berlin Tram - Chronicle - Railways in the Berlin Area - Tram , accessed on February 10, 2013

- ^ Reinhard Schulz: Tram in turbulent times. Berlin and its trams between 1920 and 1945 . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter , 4/2005, p. 98

- ↑ Kurt Schustehrus . In: Lexicon Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf from A to Z of the district office, accessed on February 21, 2013

- ^ Hainer Weißpflug: Menken, August . In: Hans-Jürgen Mende , Kurt Wernicke (Hrsg.): Berliner Bezirkslexikon, Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf . Luisenstadt educational association . Haude and Spener / Edition Luisenstadt, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-7759-0479-4 ( luise-berlin.de - as of October 7, 2009).

- ^ Berlin address book 1903 ; using official sources. Scherl, Berlin 1903, p. 31, zlb.de, ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Accessed February 20, 2013

- ↑ Iwaya Sazanami: Berlin Diary November & December 1900 . Introduced, translated and annotated by Annette Joffe. 2007, p. 65 hu-berlin.de (PDF; 8.1 MB)

- ↑ Erich Mühsam: Nonpolitical memories in: Selected works , Vol. 2: Publizistik, Berlin 1978, p. 513

- ↑ Peter Dudek: A Life in the Shadow , 2004, ISBN 3-7815-1374-2 , p. 32

- ↑ meidnergesellschaft.de: Meidner Gesellschaft e. V. , accessed December 23, 2012.

- ↑ Gudrun Blankenburg, Irene von Götz: The Destroyed Schöneberg - Ruin Photos by Herwarth Staudt , ISBN 978-3-930388-97-4 , 2015, pp. 153–155

- ↑ Carolin Stahrenberg: Hot Spots from Café to Cabaret: Musical Action Spaces in Mischa Spoliansky's Berlin 1918–1933 , 2012, ISBN 978-3-8309-2520-0 , pp. 137–158

- ↑ a b c Michael Bienert: With Brecht through Berlin , ISBN 3-458-33869-1 , 1998, p. 34

- ↑ Jürgen Schebera: Back then in the Romanisches Café - artists and their bars in Berlin in the twenties. Rev. new edition. Berlin: The New Berlin . 2005, ISBN 3-360-01267-4 , pp. 102-105

- ^ Sabine Rewald, Ian Buruma, Matthias Eberle: Glitter and Doom: German Portraits from the 1920s . 2008, ISBN 978-1-58839-200-8 , p. 137

- ↑ Jutta Hülsewig-Johnen: How in real life? - Reflections on the portrait of the New Objectivity. In: New Objectivity - Magical Realism. Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1990 (catalog for the exhibition in the Kunsthalle Bielefeld).

- ↑ Link to the picture

- ↑ Verena Dollenmaier: Die Erotik im Werk von Christian Schad , 2005, Dissertation Online , accessed on December 29, 2012

- ↑ eldoradoberlin.de: Welcome to the Eldorado! ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed February 14, 2013

- ↑ Florence Tamagne: History of Homosexuality in Europe, 1919-1939 . 2005, ISBN 978-0-87586-356-6 , p. 41

- ↑ Susanne Heim: Calories, Rubber, Careers. Plant breeding and agricultural research in Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes from 1933 to 1945 . 2003, ISBN 978-3-89244-696-5 , p. 129

- ^ Hainer Weißpflug: Joachimstaler Platz . In: Hans-Jürgen Mende , Kurt Wernicke (Hrsg.): Berliner Bezirkslexikon, Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf . Luisenstadt educational association . Haude and Spener / Edition Luisenstadt, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-7759-0479-4 ( luise-berlin.de - as of October 7, 2009).

- ↑ Levke Harders: “Stolpersteine” for Helene and Max Herrmann and for Käte Finder In: ZtG - Blog / Gender Studies at the Humboldt University in Berlin , March 19, 2009, online ( Memento of the original from April 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed February 23, 2013

- ↑ alt-berlin.info: building damage 1945, publisher: B.Aust i. A. of the Senator for Urban Development and Environmental Protection ( Memento of the original from December 18, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed February 16, 2013

- ↑ gaswerk-augsburg.de: Demolished gas containers (gasometers) and gasworks in Europe , accessed on December 23, 2012.

- ↑ Ursula Gesche: Mostly beautiful . 2005, ISBN 3-938399-10-4 , p. 64

- ↑ The cheapest day . In: Der Spiegel . No. 26 , 1948, pp. 5 ( online - June 26, 1948 ).

- ↑ kidnapping: Committed to Emil Dowideit . In: Der Spiegel . No. 36 , 1950, pp. 10 ( online - Sept. 6, 1950 ).

- ↑ DEFA Foundation film database: Interview with Berlin - 10 Years of the German Democratic Republic 1949–1959 , 1959, 5:07 pm, accessed on February 18, 2013

- ↑ Hilton: Way up . In: Der Spiegel . No. 41 , 1964, pp. 89 ( Online - Oct. 7, 1964 ).

- ^ Society / Prostitution: Hausen and Hegen . In: Der Spiegel . No. 15 , 1965, p. 67 ( Online - Apr. 7, 1965 ).

- ↑ a b The drug scene is gone: Los-Angeles-Platz has been owned by a company for three years: the private park is closed at night . In: Berliner Zeitung , August 25, 1999

- ↑ stadtentwicklung.berlin.de: Monument database / Senate Department for Urban Development Berlin , accessed on December 23, 2012.

- ↑ Landesarchiv Berlin (Ed.): Berlin Chronicle , online version , accessed on February 23, 2013

- ↑ Development plan IX-171 Rationale ( Memento of the original from December 27, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 628 kB) Berlin.de, 1997, accessed on February 28, 2013

- ^ Chronicle: Berlin in 1982 . ( Memento of the original from January 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Facts Day by Day , Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein , accessed on December 24, 2012.

- ↑ berliner-stadtplan.com: Augsburger Strasse, Berlin-Charlottenburg (Strasse / Platz) , accessed on December 24, 2012.

- ↑ a b building plan 7 13bb abz.pdf ( Memento of the original from December 27, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 652 kB) berlin.de, accessed on February 28, 2013

- ↑ Berlin land use plan , updated work card, status: November 2012, PDF ( Memento of the original from December 27, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed February 28, 2013

- ↑ Established development plan VII-B . District Office Charlottenburg, 1986, accessed on February 28, 2013

- ↑ Ku'damm Eck . In: Lexicon Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf from A to Z of the district office, accessed on February 22, 2013

- ↑ Andrej Holm : The connection to the cost rent becomes a problem in Berlin . In: MieterEcho 312 / October 2005, online

- ↑ Birgit Leiß: Waiting for a decision In: MieterMagazin , January / February 2004, Berliner Mieterverein Online , accessed on February 22, 2013

- ↑ District Office Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf of Berlin / Business Consulting: Business Street Report Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf 2005 , Annex 3: Purchasing power of business streets in relation to the district and Berlin D, 2005, PDF ( Memento of the original from January 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link became automatic used and not yet tested. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed February 22, 2013

Remarks

- ↑ There is no direct and precise evidence of the construction date. The dating can be narrowed down, however, since the Senate's funding program only began in 1986 (see Birgit Leiß: Waiting for a decision In: MieterMagazin , January / February 2004) and at the same time there are documented statements from tenants that they have been 15 years in 2003, i.e. since 1988, lived in the residential complex (see Dagmar Rosenfeld: Social housing is dear to tenants - and too expensive. In: Der Tagesspiegel , July 16, 2003, online ).

Coordinates: 52 ° 30 ′ 5.3 " N , 13 ° 20 ′ 7.5" E