Berlin question

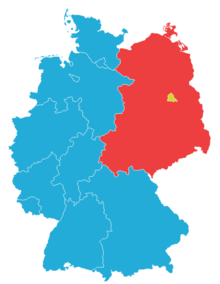

The Berlin question is the controversial special status of the four-sector city Berlin occupied by the Soviet Union after unconditional surrender at the end of the Second World War and later divided by resolutions of the Allies in divided Germany from 1945 to 1990. It was part of the German question and should be viewed in this historical epoch.

Dimensions

The Berlin question can be divided into five dimensions:

- A domestic political dimension from the point of view of the two German states ( Federal Republic of Germany and German Democratic Republic ), which tried to integrate Berlin or at least “their” district as far as possible;

- a foreign policy dimension from the perspective of the victorious powers in World War II ( United States , Soviet Union , United Kingdom and France ) who wanted to secure their influence in the former capital of the Reich ; In connection

- a geostrategic dimension that resulted from Berlin's "island location" in the Soviet occupation zone (SBZ) and that gained particular importance during the Cold War ;

- a constitutional and international legal dimension because of the special international legal position of Berlin and because of its legal relationship to the two German states;

- a humanitarian dimension, since the division of Berlin and its population brought great human suffering.

Historical development

Characteristic events and sections in dealing with the Berlin question were:

- The Yalta Conference from February 2 to 11, 1945, at which the victorious powers divided Germany into four zones of occupation and Berlin into four sectors ;

- the Potsdam Conference from July 17 to August 2, 1945, which, in the Potsdam Agreement, emphasized the responsibility of the Control Council for harmonizing the policies of the Allies;

- The Red Army of the Soviet Union (which conquered the entire area of Berlin and its surrounding areas in the Battle of Berlin , with the following unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht ) withdrew from the three western sectors of Berlin that were made up of it in the summer of 1945 due to the decisions made by the Allies;

- the resignation of the Soviet representative from the Allied headquarters on June 16, 1948;

- Currency reform in 1948 in the three western allied occupation zones and the western sectors of Berlin (introduction of the German mark , announced on June 18) and currency reform in 1948 in the Soviet occupation zone and Berlin as a whole (announced on June 22), associated with the economic division of Germany as a whole ;

- as an answer u. a. then the Berlin blockade in 1948/1949, during which the Soviet Union blocked supplies to the western sectors, which led to the formation of the Berlin Airlift ;

- The Allied Command, in the declaration of the Allied Command over Berlin of May 5, 1955, regulated Berlin's position in relation to the Western occupying powers ;

- the Berlin crisis at the end of 1958/59, in which the Soviet Union denied the continued validity of the agreements between the four powers and demanded with an ultimatum the withdrawal of the western powers from West Berlin and the conversion of the western sectors into a demilitarized Free City ;

- the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961, which led to the physical division of the city;

- several pass agreements for West Berliners to visit relatives (from December 1963);

- the subsequent relaxation with the Four Power Agreement in 1971, which was supposed to clarify the future status of Berlin;

- the creeping familiarization of all those involved with the status quo as the “capital of the GDR” in the course of the 1970s and 1980s up to

- peaceful revolution in the GDR in 1989 and with the opening of the border on November 9, 1989 the fall of the Berlin Wall as well

- the final solution to the Berlin question in the course of German reunification in 1990.

Remnants of the four-power status of Berlin with the participation of the Soviet Union remained until 1990:

- Freedom of movement for Western Allies and Soviet military patrols throughout the city

- Jointly operated flight safety center in the building of the Allied Control Council

- Headquarters of the Ministry for National Defense of the GDR outside Berlin (in Strausberg )

- Joint guarding of the Spandau war crimes prison (until 1987)

The four-power status in East Berlin

While the status was initially fully recognized by the Soviet Union and the GDR, the characteristics of the four-power status were gradually dismantled from the 1950s onwards . In detail these were:

- 1953: Abolition of the " makeshift identity card "

- 1961: Abolition of the East Berlin SPD organization

- 1961: End of city-wide freedom of movement with the construction of the Berlin Wall on August 13th

- 1962: Introduction of conscription and the presence of the NVA

- 1976: End of the separate promulgation of GDR laws in the East Berlin Ordinance Gazette

- 1976: According to the new electoral law, the East Berlin deputies were also directly elected in Volkskammer elections.

- 1977: No controls at the city limits between East Berlin and the GDR

Interests

Federal Republic of Germany

The Federal Republic of Germany as well as the Senate of Berlin (West) always stuck to the goal of German reunification and viewed the occupation and division of Germany and Berlin as a temporary chapter in history. As long as reunification seemed politically unrealistic, the ties between the Federal Republic and West Berlin were kept as close as possible in order to prevent West Berlin from drifting into the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union. Among other things, this led to a generous subsidization of West Berlin by the Federal Republic, for example through the Berlin allowance . In addition, the Federal Republic campaigned to make travel easier for West Berlin citizens who wanted to visit relatives to East Berlin or the GDR or to travel to West Germany .

" Greater Berlin " (Berlin as a whole) was named by the Basic Law as a Land of the Federal Republic of Germany as early as 1949 , because "due to the narrower version of this letter (of the three Western military governors regarding the approval of the Basic Law of May 12, 1949), in which there was no longer any question of suspending Art. 23 , the opinion prevailed in the Federal Republic of Germany that Art. 23 was not suspended and that (West) Berlin was therefore a Land of the Federal Republic (BVerfGE 7, 1 [7, 10] ) ".

Since the former obviously had to remain theory, the federal government necessarily limited itself to "Berlin (West)" and tried to integrate at least the western part of the city as politically and economically as possible. However, full legal integration failed due to the reservation of the four powers, which meant that West Berlin differed from an ordinary federal state in some important points up to 1990: For example, Berlin Bundestag members were not directly elected by the people, but sent by the House of Representatives ; they had no voting rights in the then federal capital Bonn , but an advisory function. In addition, citizens of West Berlin were not subject to federal German military service under the Four Power Agreement . The Extra-Parliamentary Opposition (APO) addressed the question of whether West Berlin authorities were allowed to provide administrative assistance to enforce the Federal German conscription in West Berlin - also through violent protest actions.

The term “West Berlin” was common, but frowned upon in official usage, especially when it was spelled “West Berlin” . Instead, “Berlin (West)” or “Berlin” for short was always written, while the eastern part of the city could be called “ East Berlin ” . This was intended to counteract a linguistic development that could create the impression that the two halves of the city are separate cities, which would have been detrimental to the idea of reunification. The debate about the politically correct name for Berlin was basically similar to that about the abbreviation "BRD" .

German Democratic Republic

The GDR, on the other hand, abandoned its goal of reunification under the socialist auspices at the end of the 1950s and tried to consolidate the division of Germany and Berlin. These efforts culminated in the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. The "island" of West Berlin, which the GDR perceived as an annoying foreign body in its own national territory , which increasingly served as a loophole for GDR refugees , was to be sealed off. While the GDR government illegally declared East Berlin to be the “capital of the GDR” but tolerated by the occupying powers, it always insisted that the “independent political unit West Berlin” was not part of the Federal Republic of Germany.

In GDR parlance , the eastern part was called “Berlin, capital of the GDR” or “Berlin” for short , while the western part was called “Independent political unit West Berlin” or simply “West Berlin” , always written without a hyphen. The aim was to create the politically desirable impression of a “real” Berlin in the east and an alien structure to the west of it.

In West German usage until the end of the 1960s, the government in Pankow, or “Pankow” for short , was often used when talking about the GDR leadership. This was to avoid speaking of the government in (East) Berlin and thus linguistically support the GDR position "Berlin, capital of the GDR" on the Berlin question.

Western powers

The Western powers USA , Great Britain and France regarded themselves as protective powers of the freedom of West Berlin. Their goal was to secure their sphere of influence in Berlin and to prevent West Berlin from being taken over by the Soviet Union. To this end, they were prepared to accept the integration of East Berlin into the GDR and thus the division of the city, which went hand in hand with a stabilization of their own position of power in the western part. In particular, their inaction against the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 was resented by many Berliners of the Western powers and perceived as betrayal of the idea of the unity and freedom of Berlin.

Formally, however, they adhered to their conception of the four-power status encompassing the entire city . The seat of the Soviet envoy in the Allied headquarters remained symbolically free during the entire period of the division . They insisted on freedom of movement for Western Allied military personnel throughout Berlin. They responded with diplomatic protest notes against violations of the four-power status from the east (e.g. military parades by the NVA on East Berlin soil). The messages of the Western powers and most of the NATO countries in East Berlin were called “Embassy to the GDR” (instead of “... in the GDR”) to emphasize that they were not on the territory of the GDR.

The defense of West Berlin was not just for humanitarian reasons. For the Western powers, especially for the USA, West Berlin functioned as an important outpost within the Eastern Bloc during the East-West conflict , which was also ideal for espionage purposes (e.g. on the Teufelsberg ).

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union disliked this function as an outpost of the West . Until the relaxation of the situation in the 1960s, the Soviet Union tried to oust the Western Allies out of Berlin and to integrate the entire city in its sphere of influence. The Soviet Union violated the four-power status of the city, especially by integrating East Berlin into the GDR. The highlights of this policy were the Berlin blockade in 1948/49 and the Berlin ultimatum in 1958, which led to the Berlin crisis.

Later the Soviet Union accepted the presence of the Western powers, but just like the GDR always insisted that West Berlin was an independent political entity and not part of the Federal Republic. The Soviet Union and GDR protested regularly and unsuccessfully against the presence of federal authorities in West Berlin and its integration into the West , interpreting the Quadrilateral Agreement of 1971 to the effect that the western sectors of Berlin are not part (constitutive part) of the Federal Republic of Germany and not part of it can be governed.

Nevertheless, the Soviet Union continued to exercise some of its occupation rights in West Berlin, namely in the form of patrols by Soviet military personnel and by participating in the guarding of the Spandau war crimes prison .

See also

- History of Berlin: Division of the City (1948–1990)

- Chronicle of the division of Germany

- Relations within Germany

- Three-state theory

- Berlin clause

Individual evidence

- ↑ Documentation of the NVA presence after 1961 ( memento of October 1, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) in the Federal Archives

- ↑ Law on the Elections to the Representatives of the German Democratic Republic (Election Law) of June 24, 1976 , Section 7, Paragraph 1, Sentence 2.

- ↑ Ingo von Münch , Basic Law Commentary, Rn. 8 to Art. 23 GG (old version).

- ↑ See also Republican Club and IDK

- ↑ Pack it up and build it up somewhere else - How the GDR is looking for new partners in the West . In: Der Spiegel . No. 9 , 1985, pp. 34-43 ( online ).

literature

- Wolfgang Heidelmeyer, Günther Hindrichs (Hrsg.): The Berlin question. Political documentation 1944–1965. Fischer Bücherei KG, Frankfurt am Main 1965.

- Ernst R. Zivier: The legal status of the state of Berlin. An investigation under the Four Power Agreement of September 3, 1971 . 3rd edition, Berlin Verlag, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-87061-173-1 .

Web links

- Berlin question , website of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation