Berlin classic

The term Berlin Classic is used to describe the urban citizen culture in Berlin around 1800. A close look at the cultural landscape in Germany in the decades before and after 1800 shows that it was not only the Weimar that has become a cultural myth that produced the classic. At the same time, the Prussian capital and residence city of Berlin was able to come up with outstanding cultural achievements. Since these corresponded to the highest standards of value on all levels of understanding of art and scholarship, they legitimize the expression “Berlin Classic”. This term was coined by the Berlin Germanist Conrad Wiedemann . At the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities , he initiated a research project “Berlin Classics. City culture around 1800 ”. The work of the scholars has questioned the problematic dominance of the term Weimar Classicism ; it has established that it is misleading, indeed wrong, to limit the high point of German culture around 1800 to the Weimar / Jena area. In addition to the many smaller centers such as Göttingen , Heidelberg , Königsberg , Leipzig and Tübingen with their important universities or Mannheim with its famous theater and the antiquities gallery, Germany had two outstanding centers, Weimar and Berlin.

Term and chronological order

The phase of high culture in the Prussian capital Berlin can be roughly dated to the time between 1786 (the year of death of Frederick the Great ) and the Congress of Vienna in 1815 (beginning of the restoration period ). The overall narrative of Berlin Classics requires a brief reflection on the concept of classical music. The concept of the classic does not mean the excellent. The terms Weimar and Berlin Classic are based on antiquity in terms of their horizon of meaning . Not only the people of Weimar, but also the Berlin artists and scholars received antiquity. For Goethe , as for many of the Berlin intellectual workers, the trip to Rome was the highlight and culmination of their own educational path and a reservoir of individual achievement. For many Berliners, socialization took place through the four neo-humanist high schools, knowledge of antiquity was the foundation of any higher education. In addition, many were trained in one of the two classical academies.

The importance of Moses Mendelssohn for the development of Berlin classical music

The Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786) can be considered the most important son of the city of Berlin. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing , the poet of the Enlightenment , got to know this "worldly wise man", as the Jewish enlightener David Friedländer called Moses Mendelssohn, in Berlin. With the friendship alliance between Lessing and Moses Mendelssohn, the foundation of the Berlin classic was laid. Lessing Mendelssohn set a literary monument in his famous idea drama Nathan the Wise from 1779. Lessing thus directly linked the idea of tolerance, particularly in the central passage of the Ring Parabola , with Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn was the founder of the Jewish Enlightenment , he had carried the Enlightenment into German-speaking Judaism. The meeting of this Jew with the Berlin society of the time was one of the high points of German intellectual history. Mendelssohn had a lasting influence on the intellectual history of Berlin through the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskala) that he initiated, especially in the 1770s and 1780s. The Haskala was a special performance by Berlin. Almost all of the Berlin salonnières were daughters, wives or sisters of the Maskilim , i.e. the representatives of the Jewish Enlightenment. Another great achievement by Mendelssohn was his translation of the five books of Moses , his Pentateuch translation . He had translated the five books of Moses, the Old Testament (for the Jews: the Torah), into German. The decisive factor was that he made this German translation in Hebrew letters. He had enabled the German Jews to use the Hebrew letters to learn their script while studying the Old Testament and at the same time learning the German language.

Weimar Classic around 1800 and its most important representatives

A comparative look at Weimar and Berlin is illuminating. It is only in this juxtaposition that the specifics of the potentials of the two cities of culture stand out sharply.

A provincial and an urban cultural project

The confrontation between a provincial and an urban cultural project sharpens the view for the spectacular achievements in both centers of German classical music. Weimar, the capital and royal seat of Thuringia, had around 6,000 inhabitants around 1800. The castle, as the center of the poor city, has served as the ancestral seat of the Ernestines , a line of the German princes of the Wettins , since the 16th century . There was prosperity only at court, there was no affluent urban middle class, 58% of the residents lived below the subsistence level.

With the Prussian Anna Amalia , a niece of Frederick the Great, the Enlightenment came to the city on the Ilm . In 1757 the Duchess gave birth to her first son, Carl August , and thus fulfilled the dynastic expectations of maintaining the male line of the otherwise threatened ruling house of the Ernestine line of the House of Wettin. After another year - at the age of 19 she had just become a widow - the second son, Friedrich Ferdinand Constantin , was born. After the early death of her husband Ernst August Constantin in 1758, Anna Amalia took over the reign of the state of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach as the duchess mother in 1759, in accordance with his will . She will remain a widow until her death in 1807. The highly educated duchess dedicated her life to art, literature and, above all, music. She attached great importance to the upbringing of her two sons.

As a prince educator , she brought the poet Christoph Martin Wieland to Weimar, along with others, in 1772 , who had taught at the University of Erfurt since 1769 . She appointed him ducal councilor and generously secured his livelihood. On September 3, 1775, after sixteen years of reign, Anna Amalia handed over the government to her now eighteen-year-old son Carl August.

Goethe's influence on Weimar

In November 1775 Goethe came to Weimar and with him there was stormy movement in the small, poor town. The author, who was only 25 years old at the time and became famous for his epistolary novel The Sorrows of Young Werther , accepted an invitation from Duke Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, who was eight years his junior. Like his father, who died early, Carl August wanted to make a contribution to the culture and art of the small and powerless duchy. The Duke expected that the lawyer Goethe, who came from a wealthy and highly educated Frankfurt patrician house, would bring glamor, money and culture to impoverished Weimar. As Weimar Minister, he will ensure that the thirty-year-old theologian and poet Johann Gottfried Herder is appointed to the city church of St. Peter and Paul in Weimar in 1776 . He will thus create the triad that is the prerequisite for the doctor, poet, philosopher and historian Friedrich Schiller to finally move with his family from Jena to Weimar in October 1799. Weimar was now making its mark in literary history. In the few years up to Schiller's death in 1805, the intensive collaboration between Schiller and Goethe, which began in the mid-1990s, unfolded and became the core of Weimar Classicism. Jena, 22 kilometers away, with its traditional university founded in 1558, was the intellectual hinterland of Weimar. The Salana (today Friedrich Schiller University) gained influence under Carl August and his (culture) minister Goethe, it became the center of German idealistic philosophy.

Schiller and Goethe: Differences in Political Thought

Schiller and Goethe differed in their political thinking. The conservative Goethe, who accompanied his duke in the war against revolutionary France in 1792, wanted the old order to be preserved in Germany at least. A democratic movement, even supported by the masses, met with deep reserves in Goethe. He feared the “rise of the mass forces”, which seemed to him “scary, dangerous and destructive”. He rejected the French Revolution theoretically and practically from its beginnings. He profoundly rejected any form of violence. Goethe relied on evolution. Schiller and Herder, on the other hand, were initially ardent advocates of the ideals of the French Revolution. The assassination of Louis XVI. on January 21, 1793, however, she was deeply indignant. Both became opponents of the political struggles in France only through the horrors of the guillotine and the dictatorship of the Jacobins . With his letters On the Aesthetic Education of Man , Schiller tried to give a comprehensive theoretical answer to the French Revolution, critical and yet committed to France's ideals. Schiller thought European. Compared to the nation-state of Europe, the still fragmented Germany lacked a national cultural center.

The Weimar elite

The Weimar elite, seeing themselves as a “cultural reserve”, reflected on transferring the large number of duchies and principalities to a German cultural nation. This culminated in "national and even European leadership claims that were made around 1800 by classical Weimar and idealistic Jena". The addressee of such an “aesthetic education” (Schiller) was not civil society, but a specific cultural elite that was supposed to act as a multiplier. Such impulses for a modern further development of society were not to be expected from this small-town court class, but rather from the philosophers, intellectuals and artists gathered in Berlin. The idealistic German intellectual history had not been able to assert itself against the political centers of power.

Berlin's cultural heyday around 1800 and its protagonists

The era of the Berlin Classic was preceded by a time upheaval. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, the power structure in Germany had also fundamentally changed. The core of the crisis at the end of the 18th century was the collapse of the old absolutist order on a political, economic, social and cultural level. Paralysis, perceptible everywhere, generated the desire for a fundamental historical renewal, formulated politically and socially: the ambitious goal of far- reaching reforms based on the findings of the Enlightenment , culturally the goal of new aesthetic coordinates.

Political and cultural consequences of the Enlightenment

A clear turning point was the death of Frederick the Great on August 17, 1786. Under him, who was much closer to the French Enlightenment than to the German intellectual world and who built his little Versailles in Potsdam with the Sanssouci Palace , Berlin's city life changed from court life far away. The end of his reign created space for a spirit of optimism. Gone were the days when German-speaking culture and the German language were ostracized by the French-speaking king. This phase of new beginnings condensed into an urban cultural concept in the Prussian capital, a radical emancipation movement that culminated in the brief, glamorous phase of the Prussian reforms . The intellectual premises were comparable in both Weimar and Berlin. Here, as there, it was about self-determination, about a concept of individuality, about emancipatory demands based on the basic convictions of the Enlightenment, sensitivity and idealism. While the Weimar Classic had its focus on poetry , philosophy and aesthetics , the Berlin Classic brought about cultural innovations and highlights in a surprising number of areas in the developing first metropolis in Germany, and the Weimar at least kept the balance. The impulses emanating from Berlin artists and scholars encompassed literature, theater and aesthetic theory as well as the fields of art, sculpture, music and architecture; they also extended to modern political science and civil society discourse.

Weimar and Berlin in comparison

The personalities who had shaped the epoch in Weimar / Jena above all - in addition to Goethe, Schiller, Herder, Wieland and important female figures such as Anna Amalia, Charlotte von Stein , Sophie Mereau or Johanna Schopenhauer - could be seen as a "parallel and counter-draft" ( Conrad Wiedemann) juxtapose the great minds of Berlin: Moses Mendelssohn, Lessing, Christoph Gottlieb Nicolai , the brothers Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt , Karl Philipp Moritz , Heinrich von Kleist , ETA Hoffmann , Carl Gotthard Langhans , Karl Friedrich Schinkel , August Wilhelm Iffland , Johann Gottfried Schadow , Carl Friedrich Zelter , Ludwig Tieck and Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder or Queen Luise , Henriette Hertz , Rahel von Varnhagen , Caroline von Humboldt and Bettina von Arnim . The great Weimar Protestant theologian and poet Johann Gottfried Herder faced the Protestant theologian, philosopher and state theorist Friedrich Schleiermacher in Berlin . While a court of muses , i.e. elitist courtly life, set the tone in the small town of Weimar , republican virtues were the order of the day in Berlin: in the famous salons that opened the doors for the citizens as well as the nobility for artistic and intellectual exchange and a new social style used; in the National Theater on Gendarmenmarkt as one of the central meeting places open to all social classes; in the Royal Academies of Science and the Arts , where scholars and artists call for discourse on their works; in the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin , where citizens and nobles, men and women sang together in a mixed choir for the first time in the world.

Rahel Varnhagen von Ense (1771–1833), steel engraving by Moritz Daffinger (1790–1849), created in 1817

Sing-Akademie zu Berlin, oil painting by Eduard Gaertner (1801–1977), created in 1843

Although the manifestations of this “German cultural bloom” around 1800 in Berlin and Weimar were quite different in their structure, it was all about an age of aesthetic ideals committed to the Enlightenment, a revolution of the spirit, an experience of art as a guide to conscious design of the world. The singular role of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe as well as that of Friedrich Schiller is not called into question. The not unfounded, time-bound claim to power of wanting to be the head of the German intellectual elite, which later, in the 19th century, was only too gladly granted, was broken by the variety of excellent artists and intellectuals that the classically romantic Berlin had to offer . The development taking place in Berlin had fundamentally different co-ordinates in that it was essentially a metropolitan bourgeois culture, i.e. a non-courtly, socially open movement of the bourgeois intelligentsia. Reconstructing this Berlin cultural epoch reveals an urban cultural physiognomy of the Prussian capital that has never been surpassed in spirit and splendor.

The network of relationships between the politically remote and Goethe-dominated small principality of Weimar and the civil culture of the Prussian capital has long been ignored. Goethe's influence in Weimar is recognizable , if he, like the other European nations had not yet united in a period in which Germany, there has created a cultural center. Weimar had never sought a connection to the urban German or even European development. This, too, is one of the main reasons that the Berlin Classics as such, that their rank has not been noticed for so long. Goethe predominated with his idea that the place of German culture is the landscape and not the city. Berlin's intellectuals and artists also considered Weimar to be the Olympus of German culture. Despite their metropolitan way of life, they were not aware of their own modernity, the groundbreaking character of their autonomous life plans. The king who succeeded Frederick the Great, his nephew Friedrich Wilhelm II. (1744–1797), opposed his uncle in his reign from 1786 to 1797, setting radically different accents. As you can see from the artists he favored, his basic orientation was civically inspired. Nevertheless, even during his reign there was no cultural interaction between court and civil culture. The tightening of censorship in 1788 by the king's minister, Johann Christoph von Woellner, marked a significant turning point for the city's intellectual climate, which was on the rise . The control and monitoring measures were still unable to stop the strong new impulses. This, as it were, antithetical policy was followed by his son, King Friedrich Wilhelm III. and his wife, Queen Luise, left.

The development in the Prussian capital Berlin

The Prussian state, which had grown up primarily militarily, was confronted with the challenges of the French Revolution and the modernity of the Napoleonic era . The Prussian capital was no longer able to represent itself in urban planning only as a dynasty (via a castle) and via the military (with the armory), but at the same time as a place of science (with the royal library, the academies and institutes as well as the one founded in 1810 University), education (theater, opera, music) and reforms ( Stein , Hardenberg , Gneisenau ). The Berlin Classic was the counterweight to the tradition of the Prussian military state and at the same time paved the way for modern lines of development in Berlin. The autonomy of art (Karl Philipp Moritz), imagination (Ludwig Tieck), science (Wilhelm von Humboldt), education (Friedrich Schleiermacher) and life plans (Rahel Levin, Heinrich von Kleist) were up for grabs. The learned and culturally affine upper class of Berlin around 1800 was more extensive than anywhere else in Germany. There was a hardly comparable reservoir of ministerial officials, officers, teachers, theologians, scientists, artisans and artists, of freelance lawyers, doctors, entrepreneurs, businesspeople, booksellers, publishers and journalists, and also of highly educated women. This reservoir then also provided the admirers of the sculptor Schadow, the readers of the newly emerging literature, the audience of Iffland's National Theater (this is where all of Berlin's cultural life gathered), the founders and visitors of the salons, the choristers of the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin , the representatives of the Prussian reforms. In the intellectual Berlin around 1800 the cultural emancipation of the bourgeois town from the court took place, with regard to the individual this meant the claim of equality between the subject and the citizen. The artists and scholars developed independently of the court, they were not sponsored by it. A major issue at the time was the civil self-determination of the individual.

The population of the Prussian capital, which is surrounded by a 17-kilometer-long customs wall, doubled in the phase around 1800 from around 140,000 to almost 300,000. In 1802, the ring wall enclosed an urban area of approx. 13.5 square kilometers. Elegant villas and summer houses were built along Tiergartenstrasse ; the nearby Potsdamer Strasse was the first Prussian street in 1792 to be expanded into a stone-paved road ; In the period that followed, the great streets were built, and the big star was laid out as the intersection of eight avenues. It was not until 1799 that Berlin was given house numbers as one of the last major cities in Europe to make it easier to find people and address the post. Now signs with the name of the street were also attached to the respective corner houses. Gold writing on a blue background was required for these signs. The city palace was the center of the capital and residence city . This is where the major roads led, from here the urban expansion took place concentrically. Around 1800 there was neither running water nor sewerage. The city was lit with lanterns that were well organized and maintained. Around 1800 Berlin was not yet a cosmopolitan city like London with its 950,000 or Paris with a little over half a million inhabitants, but it was already a growing city, a metropolis .

The Berlin population around 1800 consisted of around 85% civilians, around 15% provided the military (officers, soldiers as well as their wives and children).

Around 97% were Germans, of which 2.5% were Jews. In addition, there were 3% French, mostly Huguenots , and 0.3% Bohemians, which Frederick II had previously brought into the country.

The social structure of the Berlin population can be (greatly simplified) broken down as follows: In addition to the court and the military, there were three social groups. At the forefront of urban society was a wealthy class of independent citizens. They made up a good 8% of the population. This was followed by a middle shift with around a third self-employed craftsmen and tradespeople and around two thirds employed in manufacturing. Women were closed to all commercial professions, they made up the largest share of service and domestic staff. The (often unemployed) lower class made up a good 8% of the civilian population.

The slums that arose from the mid-19th century as a result of industrialization did not yet exist. But prosperity and elegant urban flair were largely confined to the inner city districts.

The most important protagonists of the cultural bloom in Berlin

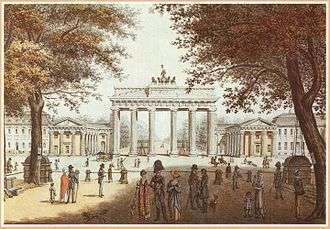

As one of the first major feats of the Berlin Classic, the architect Carl Gotthard Langhans broke through the previously prevalent Baroque design language. From 1789 to 1793 he built the Brandenburg Gate, which, crowned by the Quadriga by the sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow, still represents Berlin as a landmark in the world. It is the only one still preserved of the 20 gates that allowed entry into the city. Langhans created new urban spaces on Gendarmenmarkt , where he built the Berlin National Theater from 1800 to 1802 . In the newly built house, August Wilhelm Iffland will establish Berlin's fame as Germany's leading theater city as director and actor. To this day, the Gendarmenmarkt has the shape that Langhans once gave it.

With his early classical forms of expression, Langhans broke new ground. He played an important role in the further development of architecture, not least he paved the way for Karl Friedrich Schinkel: This Prussian architect and town planner made an important contribution to the development of a metropolitan civil culture. As the king's architect and director of the building deputation , Schinkel directed almost all building projects in the Kingdom of Prussia . He shaped the classicist urban planning concept of the Prussian capital. The Old Museum he built is one of the most important buildings of classicism. Following an initiative by Wilhelm von Humboldt, he created this museum as a universal educational facility for a bourgeois public. As the most successful and famous architect in Prussia, Schinkel initiated modern architecture and has had a major impact on the following generations to this day.

Johann Gottfried Schadow is considered the most important sculptor of this time. For more than six decades, Schadow, who was born and died in Berlin, represented the development of art in the Prussian capital. He created works with which German sculpture achieved European status. His career as court sculptor for two Prussian kings, which also culminated in many offices up to his decades-long directorate of the Royal Academy of the Arts , would not have been possible in Weimar. Schadow was the son of a tailor.

For the legendary actor, artistic director and playwright August Wilhelm Iffland, born in 1759, in the same year as Friedrich Schiller, Berlin became the most important place of work. In 1796 King Friedrich Wilhelm II brought him to the city as director of the National Theater, where he lived from then on. The house, called the Royal National Theater , became the leading theater in Germany under his leadership. In 1807 Schadow made a portrait bust of Iffland. Iffland developed the art of acting into an autonomous profession and thus helped the acting profession to gain reputation. He also ensured the independent development of the theater in Germany through fundamental reforms.

The largest German city had long since turned into a cultural center. Decisive impulses not only for the Berlin Enlightenment, but also for the Weimar Classics came from Karl Philipp Moritz, whose entire work was created in Berlin. Here he finished his autobiographical novel Anton Reiser in 1790 , which today - as the first self-analysis of a childhood trauma - is part of world literature . Due to the originality and diversity of his work, Moritz is one of the most important representatives of German literary and intellectual history of the 18th century. With his magazine on empirical psychology, he created the basis for an empirical psychology and was thus a forerunner of psychoanalysis . Moritz came from a poor background, as a military musician his father belonged to the fourth class . Moritz's career path from writer and philosopher to his appointment as professor at the Prussian Academy of Sciences as well as that of the arts would have been unthinkable in Weimar.

The composer and choir director Karl Friedrich Fasch founded the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin in 1791 out of the educated middle class of Berlin. With the offer of a mixed choir , he established a forum for bourgeois culture, where both church music and non-sacred music could be performed for the first time outside the church and independently of the court. Fasch's student Carl Friedrich Zelter continued this work, he founded modern bourgeois musical culture . The Sing-Akademie zu Berlin has achieved fame that continues to this day.

A completely new, bourgeois, enlightened salon culture arose in the Prussian capital, which was founded by Henriette Herz and, in further development, was shaped primarily by Rahel von Varnhagen. Both were Jewish and had the courage to break out of their traditional Orthodox cohesion. In the learned, emancipation-obsessed, multi-faceted development of Berlin around 1800, Rahel von Varnhagen - inspired by Moses Mendelssohn - opened a salon in 1791/92 as a woman / as a Jew, similar to that of Henriette Herz from the then Berlin intellectuals, artists and Philosophers was haunted. Nobles, scholars, artists, citizens - all were represented here and gave testimony to the looming dissolution of the estates society.

With the friendship constellation between the “romantic poet prince” Ludwig Tieck and Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder, the conceptual path to Romanticism was shown. Both poets were born in Berlin, their work was shaped by this city, and this is where they died. The crisis symptoms of the time found their way into her work in a highly idiosyncratic way. Wackenroder's early death due to illness brought his poetry to an abrupt end. Tieck, on the other hand, kept returning to Berlin, he remained connected to the city. His early work in Berlin was created during the period of upheaval around 1800; it is characterized by the urban awareness of the late Enlightenment. In his dealings with the writer and publisher Friedrich Nicolai and Iffland, he wrote contemporary Berlin literature.

Heinrich von Kleist, the enigmatic and ingenious loner, this immensely bold and modern poet, was not born in Berlin. Although he was constantly on the move throughout his life, he always returned to Berlin. He was associated with this city until his death. Recognizing the opportunities that lie in big city life, he invented and planned the Berliner Abendblätter and with them founded the Prussian capital's first daily newspaper. In Berlin he wrote one of his great plays, and here he published the most important stories available at the time. His anti-idealistic view of the world , marked by clear pessimism, is an alternative to the Weimar aesthetic. His work, in which he dared to experiment with psychological limit states, can be read as a prelude to the modern age ; worldwide he is one of the most effective and best known German authors.

The poet ETA Hoffmann made the Prussian capital a literary place for the first time. The extraordinarily multifaceted work of Hoffmann cannot, however, be limited to this perspective. The writer, the composer, the conductor, the draftsman and the caricaturist all worked in many dimensions; as a lawyer, he refused to prosecute demagogues - and all of that in a life of only 46 years.

With his commitment to the reorganization of Prussian education, the Berlin scholar, statesman, writer and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt had permanently inscribed himself in the cultural history of Berlin and gave the city an educational mandate that continues to this day. With his concept of the humanistic grammar school , he ensured a reform of the school system. It is thanks to his commitment as minister that the Prussian capital finally got its first university in 1810. The professors' appointment list drawn up by Humboldt is one of the most glamorous that has ever been submitted for a university. The cosmos of Humboldt's appropriation of the world cannot be imagined without his work on comparative linguistics and the philosophy of language . Humboldt was not only a Prussian reformer, but also an excellent scholar, a first-rate linguist.

A renewed civil society

In Berlin around 1800 a civil society of self-determined individuals developed, here an emancipated urban discourse ethic prevailed , here no artist or scholar had to be ennobled or funded . Berlin's cultural bloom around 1800 had emerged from a metropolitan bourgeois emancipation movement, each of whose representatives were shaped by urban areas in their own way . They were all characterized by the courage to experiment, outstanding creativity and the generation of a wealth of innovative ideas. The Prussian capital, which at that time was one of the largest cities in Europe, was the center of the emancipation of the Jews, their assimilation into German culture. Berlin was the place of the Haskala, the Jewish Enlightenment and the entrance gate of the Jews into the secular world of Western Europe. Berlin was at the same time the focus of a high political-aesthetic culture of discussion of the topics topical at the time: the opportunities for progress and undesirable developments offered by the French Revolution, the politics of Napoleon, the institution of the monarchy , bourgeois self-determination , the equality of the Jews, the emerging differences in intellectual history between Classical and Romance, the role of women in society.

Berlin produced scholars like Savigny or Niebuhr and the two great learned Humboldt brothers. Philosophers such as Hegel , Fichte , Schleiermacher worked in Berlin , the city had important politicians such as Friedrich Gentz , Gerhard von Scharnhorst or Carl von Clausewitz and above all Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein and Karl August von Hardenberg with their reforms. Theater greats like Iffland with its concept of a national theater for a bourgeois audience, musicians like Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy , Friedrich Christian Fasch, Carl Friedrich Zelter and Johann Friedrich Reichardt enriched the metropolis. Zelter's singing academy, financed by citizens' money, is an outstanding example of the new, independent urban bourgeois music management. Zelter, the son of a master mason, can be considered the most successful reformer of the great Berlin emancipation decades between 1786 and 1815. The Prussian residence has become classic Berlin. The development of Berlin's first modern urban civil society took place on several levels: as an urban topography, as economic growth and as the cultural emancipation of the bourgeoisie.

Aftermath: The restoration phase and its effects on the Berlin Classic

Many of the singular artistic and cultural achievements of the Berlin Classic are still impressively present today. However, the great idealistic ideas of the time around 1800, which projected a new, modern society, quickly turned into a dream for the future. Also in Berlin. Fundamental political changes have not been made by either Friedrich Wilhelm II or Friedrich Wilhelm III. been carried out. While Schinkel was able to realize many of his architectural designs in Berlin as a “refiner of all human conditions”, the enlightened society for which he had conceived them remained largely an illusion. She was only granted a brief interlude. The national awakening encountered headwinds. The reform movements were stifled during the time of the Restoration (Congress of Vienna 1815; Karlsbader Resolutions 1819 / Update 1824; persecution of demagogues in 1832): Their goal was to restore the political power relations of the Ancien Régime , that is, the conditions that characterized Europe before the French Revolution . All aspirations for freedom fell victim to repression. The struggle for a constitution, for a nation, for civil liberties, for an administration based on reason, which was supposed to implement the reformers' great modernization program, failed. The reform wheel that had started in Prussia was turned back, Germany was neither united as a nation nor renewed. The future-oriented emancipation concepts of the world declaration and world change, which were devised and discussed at the Berlin University founded by Wilhelm von Humboldt in 1810 and in its environment, remained largely pipe dreams at the time. They did not develop their effect until much later. The Jewish salons, too, in which the idea of a symbiosis of Prussia and Judaism seemed to be heading for a glamorous climax, were only a sparkling interlude in the history of German-Jewish relations.

Nevertheless: Berlin scholars and artists have taken “the risk of autonomy”. In the wake of the European Enlightenment, these artists demonstrated a modern, urban civic spirit that is still convincing today. Anticipating modernity, art and literature have shown ways of an open society. Despite the failed revolution of 1848/49, the bourgeois spirit of awakening has survived, and there has been a potential for social resistance. This enlightened civic spirit can be seen as the most valuable legacy of the Berlin classic.

literature

- All publications of the academy project are in the Wehrhahn Verlag Hannover in the series “Berliner Klassik. A big city culture around 1800 ”appeared.

- Cord Friedrich Berghahn: The risk of autonomy. Studies on Karl Philipp Moritz , Wilhelm von Humboldt, Heinrich Gentz, Friedrich Gilly and Ludwig Tieck, Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2012.

- Marie Haller-Nevermann: "More a part of the world than a city": Berlin Classic around 1800 and its protagonists. Publishing house Galiani Berlin; Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Berlin, Cologne 2018, ISBN 978-3-86971-113-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Christoph Schulte : The Jewish Enlightenment. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2002.

- ^ A b c Marie Haller-Nevermann: "More a part of the world than a city": Berlin Classic around 1800 and its protagonists. Publishing house Galiani Berlin; Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Berlin, Cologne 2018, ISBN 978-3-86971-113-3 , pp. 14ff.

- ^ A b Conrad Wiedemann: Weimar? But where is it? About size fantasies in Weimar and Jena of the classical period. In: Province and Metropolis. On the relationship between regionalism and urbanity in literature. Edited by Dieter Burdorf and Stefan Matuschek. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2008, pp. 75–101.

- ↑ Barbara Hahn (Ed.): Rahel Levin Varnhagen. Rachel. A keepsake book for your friends. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2011.

- ^ Marie Haller-Nevermann: "More a part of the world than a city": Berlin Classic around 1800 and its protagonists. Publishing house Galiani Berlin; Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Berlin, Cologne 2018, ISBN 978-3-86971-113-3 . Pp. 19-38.

- ↑ Wolfgang Ribbe : Geschichte Berlins , Volume 1. CH Beck, Munich 1988, pp. 414-421.

- ↑ Walther Th. Hinrichs: Carl Gotthard Langhans, a Silesian builder, 1733-1808. JHE Heitz, Strasbourg 1909.

- ^ Karl Friedrich Schinkel: Guide to his buildings. Vol. I: Berlin and Potsdam. Edited for the Schinkel Center of the Technical University of Berlin by Johannes Cramer , Ulrike Laible and Hans-Dieter Nägelke . German art publisher, Munich / Berlin 1912.

- ↑ Ulrike Krenzlin : Johann Gottfried Schadow. Publishing house for construction, Berlin 1990.

- ^ The complete repertoire of Ifflands Direktion, December 1796 to 1814 , on the website of the Berliner Klassik databases . Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ↑ Klaus Gerlach (ed.): The Berlin theater costume of the Iffland era. August Wilhelm Iffland as theater director, actor and stage reformer. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009.

- ^ Klaus Gerlach: August Wilhelm Iffland's dramaturgical and administrative archive. . Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Karl Philipp Moritz: Magazine for empirical soul research as a reading book for learned and unlearned 1783–1793. Ten volumes, facsimile edition with afterword and register, Lindau 1978.

- ^ Karl Philipp Moritz: Anton Reiser. A psychological novel. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1981.

- ^ Gottfried Eberle: 200 years Sing-Akademie zu Berlin. "An art association for sacred music" . Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 1991.

- ↑ Christian Filips (ed.), Carl Friedrich Zelter: Der Singemeister. Schott Verlag, Mainz 2009.

- ^ Claudia Stockinger and Stefan Scherer (eds.): Ludwig Tieck. Life - work - effect. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016.

- ^ A b Günter Blamberger : Heinrich von Kleist. Biography. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 2011.

- ^ Heinrich von Kleist (Ed.): Complete edition of the Berliner Abendblätter from October 1st, 1810 to March 30th, 1811. Epilogue and source index by Helmut Sembdner . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1982.

- ^ Marie Haller-Nevermann: "More a part of the world than a city": Berlin Classic around 1800 and its protagonists. Publishing house Galiani Berlin; Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Berlin / Cologne 2018, ISBN 978-3-86971-113-3 , pp. 306–347.

- ↑ Michael Bienert : ETA Hoffmanns Berlin , publisher for berlin-brandenburg (vbb) 2015.

- ↑ Jürgen Trabant : "World Views". Wilhelm von Humboldt's language project. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2012.

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey : German History 1866-1918. Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 978-3-406-44038-0 , 151-169.

- ↑ Hannah Lotte Lund: The Berlin “Jewish Salon” around 1800 , Walter de Gruyter Verlag, Berlin 2012.

- ^ Cord Friedrich Berghahn: The risk of autonomy. Studies on Karl Philipp Moritz, Wilhelm von Humboldt, Heinrich Gentz, Friedrich Gilly and Ludwig Tieck, Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2012.