Am or the trip to Beijing

Bin or The trip to Beijing is a short story by the Swiss writer Max Frisch . It was created in 1944 and first appeared in Zurich's Atlantis Verlag in 1945. The text was slightly revised for the new edition by Suhrkamp Verlag in 1952. The story addresses the urge of its protagonist to break out of a fixed, bourgeois life. The city of Beijing becomes the unattainable destination of all longings. The narrative was examined both for its relation to the biography of the author and for the meaning for the later work. Frisch called it “daydreaming in prose”, later he spoke more critically of “escape literature”.

content

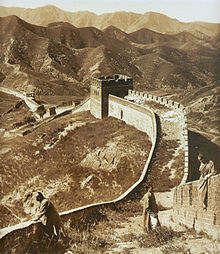

The protagonist of the story is a first-person narrator so that no name has to be mentioned, as it is called; only at the end is he called Kilian. He lives a middle class life, goes to work every day and owns a house with a garden. His wife, named Rapunzel, has just given birth to a son. His life is so happy that he hardly has any right to longing . But his evening stroll does not lead him home, but across the city and into the forest. Suddenly he stands in front of the Great Wall of China , where he meets Bin, who is resting his elbows on the wall and smoking a pipe. When asked where he is going, the narrator has no answer. So they set off for Beijing, which has to be very close, as you can already see the roofs of the city.

The trip to Beijing is taking longer than expected. It is repeatedly interrupted for weeks, months or even years. But when the narrator leaves for Beijing again, Bin is already waiting and accompanying him. The narrator felt happy and liberated on the journey if he didn't have to carry a scroll with him. Again and again she presses and disturbs him, but he doesn't just want to leave her behind. It once took a lot of effort to create, and its content is extraordinarily weighty. On the journey the narrator meets a saint made of sandstone and people from his previous life. As a teenager he sees the first naked woman bathing in the sea again and follows her into the darkness of a barrel lying on the beach. He meets the painter Anastasius Holder again, to whom he did not reveal how much he was impressed by one of his watercolors and who fell to his death that same day. He dances one more time with his childhood sweetheart Maja. She is as young as she was then, but now she says you to him because he has become a master. He remembers a suicide who was put off suicide because he tried to get into the water and saved the life of a boy; since then he has been ashamed of the water.

When he has almost reached Beijing, the narrator wants to assume his role in a house. But the house turns out to be a draft of his own imagination, the daughter of the house reminds of Maja, the prince of China comes to visit and wants the narrator to build a new palace for her. The narrator stays in the house for a long time, and he almost fears that Bin might reappear and warn him to continue his journey. But in the end he gets tired of the house. It is no longer the house of his dreams, instead it is fixed, its faults cannot be changed, it now seems strange and desolate to him. He escapes with the Chinese Maja. She too is driven out into the world by an inner urge and wants to know from the well-traveled person whether he knows the goal of her longing, whether it really exists. But the young girl's dreams, unlike his, are still unbroken. At the first opportunity she breaks up with a young fellow. The only thing left for the narrator to know is that she loved him; he takes refuge in alcohol.

When Kilian visits a concert, Death appears and pats him on the shoulder. Kilian either has to come with him himself or nominate a replacement for himself. Kilian cannot bring himself to choose a musician or concert-goer. He blindly taps someone on the shoulder who turns out to be his father and dies. At the same moment Kilian becomes a father and his son is born. In the end Kilian is back home. Rapunzel is preparing breakfast for him. He knows he will never come to Beijing. Only the facial features of his son remind him of Bin.

shape

Gertrud Bauer-Pickar saw Bin as a mosaic of memories, dreams and experiences. At different stages of the journey, reality and imagination mix. Using hypothetical stories, the possibilities of the present are explored, introduced by phrases like “Or it could be”. The dreamlike character of the story is underscored by indefinite times (“often”, “sometimes”, “then”, “soon”) and the location (“outside”, “inside”, “over there”). Motif recurring action elements change their appearance, for example the moon, which resembles a cat, a gong or a fat face, or the saint, who at the end stands as a trinket on the chest of an apartment. The protagonist of the story is divided into three characters: the nameless first-person narrator, his complementary 'you' named Bin and Kilian, only mentioned in the third person. Both the I and the am remain representative models whose individuality is not detailed.

The nameless narrator is offered to the reader as a figure to identify with, as everyone. Several times the reader is addressed directly and thus drawn into the story. The first sentence already reads: “It cannot be seriously assumed that there are people who do not know Bin, our friend.” Later on, the inclusive We is used in some places: “All of a sudden, after years of waiting, sees one is concerned with the question of what we are actually expecting at this place. ”With ironic comments, Frisch breaks through the narrative, thus calling the reader's attention to the various levels of reality. For example, he remarks about his narrator, "to whom we have overburdened the role of a narrative self so as not to have to name any names", in the following paragraph: "We could have called him Kilian", what he did with the change to the third person now also does. Elsewhere he chats about the main character: "In other words: he probably drank a little too."

interpretation

I am

The figure Bin was interpreted by various interpreters as Kilian's better self, his alter ego , his doppelganger, travel guide, the embodiment of his possibilities or wishes. At the same time he is referred to as part of all people, detached from Kilian. In the course of the plot he appears several times in the role of a supernatural assistant from the fairy tale . Its function for the narrator is reminiscent of the function of the later diary for Max Frisch: I comment, give answers, explain facts or ask the narrator the questions he wants to answer. I and Bin are two expressions of a self from which Bin was externalized in order to enable a dialogue with oneself.

The narrator's dialogue with Bin is reminiscent of writing, and the narrator actually admits: “Sometimes I still write to Bin. There are not always friends when something happens; there is almost always a pen, a piece of paper, an economy ”. In storytelling and writing to Bin, Kilian can experience his poetic, literary self. Only through the collapse of I and Am does the whole, the real human being arise. The narrator knows “that I am only in this longed-for place through the means of the dream.” Only in the area of the dream, in the storytelling, can the narrator claim: “I […] am.” Hans Schumacher directed the name Bin as Syllable from Al-Bin ab, Albin Zollinger , the writer who was admired by Frisch in his youth.

The "you" of the story is the woman, the archetype of the female anima , whom the narrator encounters in various forms in the course of the story: the naked woman in the bin, the courtesan peach blossom, his first love Maja and the young Chinese woman with whom he tries in vain to repeat the memory. The ending is taken from the fairy tale Rapunzel : after the "prince" has wandered blindly through the world, he happily finds his way home to his wife Rapunzel.

The trip to Beijing

Beijing does not represent the real Chinese capital, but a place of imagination, a state of thought. Nevertheless, Beijing can be geographically located in the Far East . It is a place of Eastern philosophy and wisdom: the question “what are you actually doing?” Is immediately commented on with “Oh, this Western question!”. Beijing is also a place of peace, while in the West: “There is still war over there”. In contrast to the hectic, automated, monotonous West, Beijing stands for leisure and contemplation, for waterfalls and butterflies, in short for a better life, which Frisch borrows from a sentence by Albin Zollinger: "Longing is our best."

The journey follows a river. The narrator expects Beijing to be the destination where it flows into the sea. The river separates the real from the imaginable, just as it separates the present from the past and possible future. It is the flow of time that enables the narrator to jump into different time levels. At the same time it is also the flow of life. It continues to flow, even if the narrator does not advance: “Am […] I think it drives us away. By thinking that we are staying in place, by resting and talking and lingering, it drives us off ”.

The journey to Beijing is a journey outside of space and time. It should lead to a night without borders, as the narrator never succeeds in overcoming his inner limits. His internal conflicts are reinterpreted as external distances. By crossing the Great Wall of China, the narrator has overcome the boundary between the conscious and the unconscious. He seeks the way to the creative, which lies in the unconscious: “It would be different among real people, among creative peoples”. Beijing is not reached in the end, but the narrator's change of consciousness already lies in the departure for self-fulfillment, the journey itself becomes the goal.

The role

The narrator has ambivalent feelings about the role that the narrator always carries with him. On the one hand, he wants to get rid of her because he knows that it is only she who keeps him from being absorbed in his longing. In this sense it stands for the everyday life of the narrator that he wants to shed. At the same time the role is precious to him, he doesn't want to lose it because it contains the sum of his experiences, the irrefutable proof of his existence. The role stands for both meanings of the word, the role that the narrator plays in his life and the paper role as a record of his existence. By reaching his goal, the role of the narrator would be overcome: “A role that would be left standing in Beijing would be lost forever.” But the choice of words shows the inner resistance to giving up the role and thus also to the self-realization that is striven for.

When the narrator wants to hand over the scroll to a house for safekeeping, it takes on material form in the house itself. The house was built according to Kilian's plans, which are recorded in the role. The stay in the plans that have become reality leads to the narrator's alienation from himself and ultimately to a split in his personality: through a window he observes himself at the celebration with the prince, observes his own social behavior like that of a stranger. The narrator does not recognize the house he designed himself in reality. By implementing a plan, all other possibilities inherent in the original design are negated: "Everything that is finished ceases to be a home for our spirit."

The passage of time

The journey leads through time in two ways. On the one hand, in the narrator's subjective sense of time, it begins in spring and leads over summer to autumn. At the same time, the narrator develops from adolescent to adult. The beginning of the story symbolizes the youth. Memories do not yet play a role, the longing is directed towards the future, towards the new, it still seems unlimited, the goals attainable, Beijing cannot be far away.

In the middle section, the summer, it comes to the realization that time does not stand still. For the first time, past moments are recalled, missed opportunities regretted. For the first time there is also an attempt to explain life through philosophical considerations. Boredom kicks in, depression and loneliness follow and lead to a suicide attempt. This episode, told by the narrator as if it were happening to someone else, is an alternative possibility of his life, a life without bin.

Then the story goes into the autumn of life, dominated by the knowledge of its limitations. The narrator lives out his longings once again, tries to repeat his first love with a new Maya in order to come to the realization that a return is not possible. Death pays its respects for the first time, and Kilian knows that the next time it will not escape it through someone else's sacrifice. Kilian's role changes from son to father. Logically, his own father dies, whose position Kilian himself now takes. On the autumn day of the epilogue, the ripe fruits of last summer are still hanging in the trees, while the seeds for next spring have already been sown. The picture represents the father and the newborn son. The narrator's journey with Bin was also a journey to his own death, in which Bin acted as Charon the ferryman .

Autobiographical background

The early novels and stories of Max Frisch are all located in the field of tension between a bourgeois and an artistic existence, two alternatives for a life plan, between which Frisch himself was at the time split. In 1936 he broke off a course in German and enrolled at the ETH Zurich to study architecture . In the following year, after the story Answer from Silence had clearly taken a position for bourgeois life, Frisch burned all his manuscripts and renounced the profession of a writer before he relapsed literarily again in 1939 with the war diary leaves from the bread sack. In 1942 he married the architect Gertrude Anna Constanze von Meyenburg . In an interview with Heinz Ludwig Arnold he explained: “I then decidedly committed to a bourgeois existence, and then got married in a very bourgeois manner. So I was a conscious citizen, someone who wants to be a citizen, and I paid my price for it and had my experience with it. "

Against this background, the Frisch biographer Urs Bircher deciphered the story biographically. Like Kilian, the architect Max Frisch also designed houses. Like Kilian's wife, Trudy von Meyenburg was nicknamed "Rapunzel". The apartment described, in which Kilian lives so happily that he believes he has no right to longing, is the Zurich apartment where the Frisch family moved in 1942. Kilian's newborn son corresponds with Frisch's children born in 1943 and 1944. According to Bircher, Frisch's theme in Bin is the longing to break out of his bourgeois life and turn to art. Despite his confessions for the bourgeoisie, the longing cannot be suppressed. Through the story that Frisch dedicated to his wife, he confessed to his Rapunzel that he would always leave for Beijing anew, that he would be tempted anew by a Maja, but that he would always come back to her in the evenings Will return apartment. Bircher concluded with the words: "From a biographical point of view, Bin is a life confession, the attempt to tell the wife an allegory of himself and his life's needs."

The later biographer Lioba Waleczek restricted Bircher's interpretation. For them “such a narrow biographical interpretation remained problematic”. But she also assessed that Frisch was on the move, in search of change and in the exploration of his self-image and that his role as a writer was thematized in the story. In his personal life, Frisch only drew the consequences of his turmoil between bourgeois life and art ten years later. After the success of his novel Stiller , he separated from his family in 1954. The following year he gave up his architecture office and from then on devoted himself only to writing.

Position in Frisch's oeuvre

Bin or Die Reise nach Peking is often seen as the first step in Frisch's early work on the themes and style of his later work. It is Frisch's first major first-person story. At the same time, it is Frisch's first work in which the ego is split into two figures, a trick that Frisch should use more often in his later works. The hypothetical stories in Bin already take the basic motive out of My name is Gantenbein : “I imagine”. Individual plot elements can be found in later works. The continuous theme of the role that the narrator carries with him against his will is taken up in an episode of Stiller in which Rolf wanders through Genoa with an imposed package of flesh-colored material. The character of Isidor is also known from Stiller , the name Kilian from the drama Santa Cruz . Kilian's encounter with death is reminiscent of the diary sketch The Harlequin .

The narrative attitude of Bin left the previous brooding, serious and problematic style of the early work behind. Jürgen H. Petersen saw the cheerful, poetic tone from Bin as a result of the more feuilletonistic approach of leaves in a bread sack . Frisch himself described the story in 1948 as “dreaming in prose”, and in 1974 as a “tender, romantic structure” of which he was not ashamed. Nevertheless, he noted critically that he had withdrawn "into an ivory tower" with such "escape literature" during the Second World War. He couldn't write about Dachau or at least about the situation in Switzerland: “I didn't have the means, maybe I didn't have the courage either - I don't mean the courage to face the outside world, but the courage to let yourself and trusts his ability to represent these things -; it only began towards the end of the war, when I began to portray the world that beset me and no longer viewed literature as a refuge. "

reception

Bin or The trip to Beijing was received with great acclaim in the press. Emil Staiger read the text as a parable for “something absolutely valid” that reveals the “true and impressive Max Frisch”. Hans Mayer saw in Bin a “vacation trip with a return ticket”, which was nevertheless a “'sensitive journey', elegiac, dreamlike, playful, at times also idyllic”. Frisch tries "to shed light on everyday life through lyrical language." This contained "something of that 'romanticization' of everyday life that Novalis dreamed of."

Peter Bichsel opposed reading Bin merely as apolitical escape literature: “When we read Bin with Primo , it was not a suspicion, but the absolute certainty that this was about change, about departure. We understood this entirely politically. It was our chance. Our chance to get away from where we are still. ”The sinologist Wolfgang Kubin called Bin or Die Reise nach Peking his favorite book.

literature

Text output

- Max Frisch: Bin or the trip to Beijing . Atlantis, Zurich 1945 (first edition)

- Max Frisch: Bin or the trip to Beijing . Library Suhrkamp 8, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1952, ISBN 3-518-01008-5 (revised new edition)

Secondary literature

- Peter Bichsel : When Primo Randazzo ordered us to “Bin” . In: Walter Schmitz (Ed.): Max Frisch . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-518-38559-3 , pp. 92-96.

- Manfred Jurgensen : Max Frisch. The novels . Francke, Bern 1976, ISBN 3-7720-1160-8 , pp. 30-45.

- Hans Mayer : Bin or the trip to Beijing . In: Hans Mayer: Fresh and Dürrenmatt . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-518-22098-5 , pp. 91-93.

- Walter Schmitz : Max Frisch: The Work (1931–1961) . Studies on tradition and processing traditions. Peter Lang, Bern 1985, ISBN 3-261-05049-7 , pp. 114-123.

- Hans Schumacher: On Max Frisch's "Bin or The Journey to Beijing" . In: Walter Schmitz (Ed.): About Max Frisch II , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1976, ISBN 3-518-10852-2 , pp. 178-182.

- Linda J. Stine: Chinese Daydreaming: Fairy Tale Elements in "Bin" . In: Walter Schmitz (Ed.): Max Frisch , pp. 97–105.

Web links

- Charles Linsmayer : Max Frisch . Published in: Swiss literature scene. 157 short portraits from Rousseau to Gertrud Leutenegger . Unionsverlag, Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-293-00152-1 .

- Harri Hemminki: The “time” in the story “Bin or Die Reise nach Peking” by Max Frisch: A structural text analysis . Pro graduate thesis at Jyväskylä University , 2003 (pdf file)

- Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin Or The Trip To Beijing: A Structural Study . In: Forum Vol. XVII Autumn 1976 Number 4 , Ball State University , pp. 61-70. (pdf file, English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-518-06533-5 , p. 605.

- ↑ Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin Or The Journey To Beijing: A Structural Study , pp. 61–62, 64.

- ↑ a b Manfred Jurgensen: Max Frisch. The novels , p. 30.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 603.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 604.

- ↑ Linda J. Stine: Chinese Dreaming: Fairy Tale Elements in "Bin" , p. 99.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 650.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 653.

- ↑ Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin Or The Journey To Beijing: A Structural Study , pp. 68–68.

- ↑ Linda J. Stine: Chinese dreaming: fairy tale elements in "Bin" , pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 656.

- ^ Walter Schmitz: Max Frisch: Das Werk (1931–1961) , p. 120.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 636.

- ↑ Manfred Jurgensen: Max Frisch. The novels , p. 40.

- ↑ Hans Schumacher: On Max Frisch's "Bin or Die Reise nach Peking" , p. 180.

- ↑ Linda J. Stine: Chinese Dreaming: Fairy Tale Elements in "Bin" , pp. 102-103.

- ^ A b Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 608.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 606.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 643.

- ↑ See paragraph: Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin Oder Die Reise nach Peking: A Structural Study , p. 62.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 611.

- ↑ See paragraph: Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin or Die Reise nach Peking: A Structural Study , pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Linda J. Stine: Chinese Dreaming: Fairy Tale Elements in "Bin" , p. 98.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 622.

- ^ Walter Schmitz: Max Frisch: Das Werk (1931–1961) , p. 117.

- ↑ See section: Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin or Die Reise nach Peking: A Structural Study , pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Manfred Jurgensen: Max Frisch. The novels , p. 33.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. First volume , p. 645.

- ^ Walter Schmitz: Max Frisch: Das Werk (1931–1961) , pp. 120–121.

- ↑ See the section: Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin Or Die Reise nach Peking: A Structural Study , pp. 63–69.

- ^ Walter Schmitz: Max Frisch: Das Werk (1931–1961) , p. 123.

- ^ Heinz Ludwig Arnold : Conversations with writers . Beck, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-406-04934-6 , pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Urs Bircher: From the slow growth of an anger: Max Frisch 1911–1955 . Limmat, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85791-286-3 , pp. 119–123.

- ↑ Lioba Waleczek: Max Frisch . Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-423-31045-6 , p. 60.

- ↑ Alexander Stephan : Max Frisch . CH Beck, Munich 1983, 178 pages, ISBN 3-406-09587-9 .

- ↑ Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin Or The Journey To Beijing: A Structural Study , p. 61.

- ↑ Gertrud Bauer-Pickar: Bin Or The Journey To Beijing: A Structural Study , p. 67.

- ↑ Manfred Jurgensen: Max Frisch. The novels , p. 43.

- ↑ Jürgen H. Petersen: Max Frisch . Metzler, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-476-13173-4 , pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Max Frisch: Collected works in chronological order. Second volume , p. 589.

- ^ Heinz Ludwig Arnold: Conversations with Writers , pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Urs Bircher: From the slow growth of an anger: Max Frisch 1911–1955 , p. 124.

- ↑ Hans Mayer: Bin or Die Reise nach Peking , pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Peter Bichsel: When Primo Randazzo ordered us to “Bin” , p. 96.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kubin : From the workshop of a literary historiographer . In: Thomas Borgard, Christian von Zimmermann, Sara Margarita Zwahlen (ed.): Challenge China . Haupt, Bern 2009, ISBN 978-3-258-07358-3 S, 86.