Buster Keaton

Buster Keaton [ ˌbʌstər ˈki: tn ] (actually Joseph Frank Keaton ; born October 4, 1895 in Piqua , Kansas , † February 1, 1966 in Woodland Hills , California ) was an American actor , comedian and film director .

Along with Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd, Keaton was one of the most successful comedians of the silent film era . Because of his deliberately serious, stoic expression, he was called The Great Stoneface and The Man Who Never Laughed . Another trademark was his pork pie hat , a round, flat hat made of felt.

Due to his acrobatic talent, he made a career in vaudeville with his parents as The Three Keatons as a child , before he appeared in the films of Roscoe Arbuckle at the age of 21 . Three years later he began producing his own very successful comedies. With Der Navigator in 1924 he achieved his breakthrough and connection to the most popular comedians of his time, Chaplin and Lloyd.

In the wake of the financial failure of his lavish film The General , Keaton became an actor for MGM in 1928 . In 1933, Keaton, who was meanwhile alcoholic, was fired due to ongoing conflicts with the company's board of directors. In the period that followed, he was initially very successful as an actor in films by other directors, but was then increasingly forgotten. In the 1950s the rediscovery and appreciation of his technically innovative silent film comedies began, which today are counted among the most important works in film history.

Life

Childhood and youth

Joseph Frank (later: Francis) Keaton was the first child of Joseph (Joe) Hallie Keaton and Myra Keaton, b. Cutler was born in Piqua, a small town in the American Midwest . In line with family tradition, the son was named after his father, but also after his maternal grandfather. His parents reportedly gave him the name Buster after he had survived a dangerous fall down the stairs unharmed. This is said to have caused the escape artist Harry Houdini to comment: “That's sure some buster your baby took!” (For example: “That was quite a fall that your baby put there”). Marion Meade, however, suggested in her biography of Keaton that the legendary Houdini only found its way into the anecdote afterwards. What is certain is that Keaton was the first to wear the later name Buster , which later appeared more frequently .

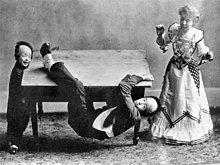

His parents were touring the Mohawk Indian Medicine Show at the time of his birth , a mix of miracle healing and entertainment that was common at the time . From 1899 Myra and Joe Keaton sought their luck in the vaudeville shows in New York . After a disappointing start, the two of them used their son's talent from October 1900 to survive falls unscathed and without complaint, and took him with them on stage. As a "human mop" he was ruthlessly thrown into the scenes by his father, but to the delight of the audience. These burlesque , slapstick-like numbers represented the harsh upbringing of a son. Buster learned early on that the less he did, the more the audience laughed . The extraordinarily brutal appearing performances developed into an audience success. The Two Keatons soon became The Three Keatons, starring Buster.

But the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children ( NYSPCC or, after one of its founders, Gerry Society ) was also interested in the child. This non-profit organization reported abuse and exploitation of children. The parents tried to counter this by portraying Buster as a short adult or a few years older. With only one performance ban, in New York State from 1907 to 1909, the Keatons got off lightly. Joe Keaton had to drop his plans, however, to bring the whole family - now expanded to include the children Harry (nicknamed "Jingles") and Louise - on stage. Buster Keaton himself later protested against allegations that the blows and falls he suffered on stage were a form of child abuse.

Since he spent almost all of his childhood and youth in vaudeville, Keaton never received a regular school education. At the age of 21 he decided to break away from his parents artistically and to look for his own commitment. He was now too big for the boy he was supposed to play; The number also suffered from his father's already pronounced alcoholism .

The way to film

From April 26, 1917, Keaton was to appear in New York in a revue by the legendary Shubert brothers entitled Passing Show . By chance, however, in February he met an old friend from his youth who was now working in a film studio . This invited Keaton to visit the studio located in a former department store on Manhattan's 48th Street; there he met Roscoe Arbuckle , who used to be employed by Vaudeville and was now considered the most popular comedian next to Charles Chaplin . When Keaton let himself be guided through the studio, Arbuckle was working on his first film under his new producer Joseph Schenck .

Keaton was initially rather skeptical towards Arbuckle, as he had taken over stage numbers from the Keatons without being asked. In addition, the "moving images" were seen as competition for vaudeville; Keaton's father Joe had strictly rejected her. But the technique of filming fascinated Keaton. The offer Arbuckles, stante pede appear in the film, he therefore did not strike out: The Butcher Boy (1917) is regarded as Keaton's film debut. In the sequence improvised by Buster Keaton he can already be seen with his later trademarks, the almost immobile facial expression and the flat pork pie . An anecdote has it that on the same day he borrowed a camera from the set and curiously took it apart at home. Keaton enthusiastically let his lucrative stage contract terminate in order to take part in the films of Arbuckle for far less money.

By 1920, Keaton made 15 two-reelers ( short films of around 20 to 25 minutes in length) as a partner of Arbuckle, thus becoming familiar with every facet of filmmaking. Even if he had got used to the "poker face" for his stage appearances from childhood, Buster can be seen laughing hysterically in the films of this phase of his career. But Keaton's subtle understanding of humor and his experiences from vaudeville shaped the style of Arbuckle's films more and more over time. He designed not only most of the gags and the action but soon led next Arbuckle directed .

After his military service from July 1918 to March 1919 with the American Expeditionary Forces in France, Buster Keaton returned to Arbuckle's Comique Studio despite better offers . Since 1917, the studio has been based in the still young Hollywood , which offered a better climate and thus more days of outdoor shooting than New York. After only three more joint films, however, Arbuckle accepted the offer at the end of 1919 to shoot full-length films (60-70 minutes at the time) with the production company Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount Pictures ). Arbuckle's previous producer Joseph Schenck then offered Keaton to take Arbuckle's position and make his own films in creative freedom. The new film studio Metro (later merged into Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer ) was to take over the distribution of all Keaton films.

In the same year, Keaton was hired as the leading actor for the feature-length comedy The Saphead, produced by Metro . The criticism of Keaton's first major film appearance was benevolent but not enthusiastic: "Buster is a natural, agreeable comedian."

Buster Keaton Studios

Buster Keaton shot his films in Charlie Chaplin's old studio. For the time being, he withheld his debut, Buster Keaton Fighting the Bloody Hand (1920). Keaton's first publication Honeymoon in the Prefabricated House from 1920, however, is now considered a classic of the genre. The elaborate short film is about the ultimately disastrous attempt by a newlywed couple to build a prefabricated house according to instructions.

Of the 19 short films from the Keaton studios, Buster and the Police (1922) are among the best known today : At the height of the film, hundreds of police officers chase Buster through the streets of New York. This motif can be found again in various ways in his full-length comedies Seven Chances (here there are hundreds of brides ready to marry, and finally countless boulders) and The Cowboy (with a herd of cattle in Los Angeles).

It was only relatively late - compared to the other great silent film comedians of the time, Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd - that Keaton switched to full-length comedies. While his first attempt at Drei Zeitalter (1923) consisted of three short films and had the typical, comic- style humor of short films, Keaton changed his style fundamentally with Darn Hospitality . From now on he placed more emphasis on the credibility of the gags, out of the conviction that otherwise he would not be able to tie the audience to the story.

In Darn Hospitality , alongside his father Joe Keaton, his then wife is the only time to be seen in one of his films. Natalie Talmadge was the sister-in-law of his producer Joseph Schenck. Keaton married her in 1921. Their first son, Joseph, can also be seen in the film at the age of one.

With The Navigator , Keaton finally caught up with the two most popular film comedians of the time, Chaplin and Lloyd. It remained one of his financially most successful productions. In the film, made in 1924, he and his partner Kathryn McGuire end up on an abandoned, huge ship that drifts aimlessly in the ocean.

The next films ( Seven Chances , The Cowboy and - as his greatest commercial success - The Killer of Alabama ) confirmed the extraordinary popularity of Keaton, whose fame was based on his inventing and performing spectacular stunts. The shooting was therefore always associated with great risks: In one scene at the height of Verflixte Gastfreundschaft (a stunt at a waterfall) he swallowed too much water; his stomach needed to be pumped out. At Sherlock, Jr. (1924) his head was thrown violently against rails. Afterwards, Keaton suffered from severe headaches, which disappeared after a few days. The fracture of a cervical vertebra , which he apparently contracted, was discovered accidentally and only years later during x-rays .

Financial disaster

With Der General , an epic comedy made in 1926 and set at the time of the American Civil War , Keaton took his credibility and authenticity claims to extremes : he let a historic steam locomotive plunge into the depths. This single scene is one of the most expensive in the entire silent film era. The contemporary audience, however, was not enthusiastic about the film, and most of the critics dismissed the work, which is now considered a milestone, as boring.

After this flop, his producer Joseph Schenck increasingly took control of Keaton's productions and - against Keaton's will - provided scriptwriters and directors to the side. Above all, he paid more attention to the budget . The following film Der Musterschüler (1927) suffered significantly from the new restrictions, even if Keaton's handwriting is unmistakable. Ultimately, the more conventional comedy didn't make more money at the box office than The General .

In Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928) Keaton realized what is perhaps the most dangerous and legendary stunt of his career by tilting a house facade on him and only being spared by a small gable window. It would be his last independent production. The costs were once again driven up when the finale of the film including the existing buildings had to be changed because a devastating flood had made headlines in America shortly before and therefore the originally planned flood was supposed to become a hurricane . The film's revenues lagged behind those of The General and The Model Student .

While filming was still in progress, producer Joseph M. Schenck, now President of United Artists , broke his contract with Keaton. He suggested that he sign a contract with MGM , which is now the largest film studio. Both Chaplin and Lloyd warned Keaton about the counterproductive studio system. But Keaton was convinced by Joseph Schenck. He later described this step as the biggest mistake of his life.

Downfall at MGM

At MGM, Keaton should submit to the rigid studio system. For example, it was required to work strictly according to an existing script . This contradicted Keaton's previous working style, which - like other silent film comedians - drew the majority of his ideas from improvisation and never worked from a script. There were serious tensions between the powerful producer Louis B. Mayer and Keaton, who was initially able to fight for a certain amount of freedom. His first MGM film The Cameraman (1928) is considered to be the last in the style of Keaton. The studio booked the great success of the comedy for itself and not only withdrew from Keaton long-term employees who had switched to MGM with him, but also artistic influence. Instead, he was given advisors who were supposed to intervene in the development of the film. This can be clearly seen in his last silent film, Tough Marriage (1929). Although this time it was strictly based on an exact script, the film seems, in the opinion of critics, much less stringent than the classic Keaton comedies.

Already a defiance marriage , which emerged in the time of the aspiring sound film , Keaton wanted to produce as a sound film. He wasn't worried about his voice or pronunciation. But as an employee he had no influence on the studio's decisions. When he was then cast in sound films, Keaton also criticized the emerging fashion of foregoing visual comedy in favor of silly dialogues. He had to shoot each of the comedies that Keaton was reluctant to make three or four times, each time in a different language: This is how Hollywood sound films were marketed worldwide in the early 1930s. Jim Kline notes in his book The Complete Films of Buster Keaton about Keaton's first talky-about film Free and Easy (1930, MGM) : “Buster talks! Buster sings! Buster dances! Buster looks depressed! "(" Buster speaks! Buster sings! Buster dances! Buster looks depressed! ") Almost forgotten today, this and the following films made more money than the silent films of the Keaton studios, especially Sidewalks of New York ( 1931), a comedy Keaton disliked from the start. In 1932 MGM tried to establish Keaton and Jimmy Durante as a comedian duo. The rather quiet Keaton was very unhappy about the deliberately loud and quick-talking Durante as a partner.

During this time, Keaton's alcoholism, which had already started with the end of his independence, intensified. On filming dates he usually appeared drunk or not at all. His wife Natalie Talmadge filed for divorce in 1932 - long arguments about the division of property and custody of the two children ensued. In 1933 his contract of employment at MGM was terminated after several disputes with Louis B. Mayer. In the same year, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, perhaps his closest friend, died. His reputation and career were meanwhile ruined , despite acquittal after a murder charge. Keaton himself made negative headlines. The private, professional and financial problems made his alcohol addiction worse. He married his private nurse Mae Scriven, who was supposed to help him during rehab. The marriage was divorced after less than three years. With the support of his doctor and his family, Keaton managed to get rid of the addiction as far as possible and to keep himself and his family afloat with small commitments.

For the general public, he was practically out of sight and out of consciousness. He first appeared in cheaply produced short films in small educational studios . The promising French production Le Roi des Champs-Élysées (1934) with Keaton in the lead role did not receive the hoped-for attention. From 1937 Keaton worked again at MGM - primarily as a gagman behind the scenes, for a fraction of his last salary. Among other things, he devised gags for films with Red Skelton , the Marx Brothers and Laurel and Hardy . While he was friends with both Red Skelton and admired Laurel and Hardy very much, he later commented negatively about the working style of the Marx Brothers: They did not take the comedy seriously. From 1939 to 1941 he directed ten short comedies for Columbia . Although these were cheaply produced and not very original, Keaton's ability to work was restored after the alcoholic illness. Through friends, he also occasionally got the opportunity to work in large studio productions: for the comedy Hollywood Cavalcade ( 20th Century Fox , 1939), he took over the direction of a short film-within-a-film segment in which he also played. After a year without a film engagement, he was sporadically seen again from 1943 in some comedies by Universal and other, smaller studios. In San Diego, I Love You (Universal, 1944), there is a moment rare in Keaton's films: Buster smiles warmly.

Due to the sparse film work, Keaton took some stage and variety engagements in the 1940s , both in the USA and in Europe, and thus returned to his roots. Among other things, he made a number of successful guest appearances at the prestigious Cirque Medrano in Paris from 1947 - together with his wife: In 1940, Keaton married Eleanor Norris, who was twenty-three years his junior and who was a dancer under MGM contract. The happy marriage lasted until the end of his life.

Rediscovery

In a 1949 article in Life Magazine, influential film critic James Agee was deeply impressed with the memory of “the 'most silent' of all silent film comedians” (Keaton). American film clubs began to show his films again - if they still existed: With the exception of The General , The Navigator and some of his short films, Keaton's silent films were considered destroyed or lost.

Also in 1949, Keaton took on a supporting role in the Judy Garland musical Back in the Summer , which was his first substantial appearance in a major Hollywood film in 15 years. The still young medium of television began to show an interest in Keaton: Keaton played in new sketches for The Buster Keaton Comedy Show (recorded in front of a live audience, 1949) and The Buster Keaton Show (1950–51) - mostly with his wife. However, Keaton ended these ranks after a short time. This was followed by guest appearances on talk shows, series and other programs (including in Candid Camera , the original version of Hidden Camera ). New fields of activity also opened up for Buster Keaton in the field of advertising. He became the star of several industrial films and shot television commercials for Colgate , Alka-Seltzer, 7 Up , Ford , Milky Way , Budweiser and others between 1956 and 1964 .

Of his numerous cameo appearances in films from a wide variety of studios, Billy Wilder's Boulevard of the Twilight (1950) deserves special mention: he quasi portrays himself in a macabre-looking bridge group of forgotten silent film stars. Two years later there was a similar memorable, albeit short one Appearance in Charlie Chaplin's limelight : For the first time, the two greatest comedians of the silent film era can be seen together in one film, significantly as aging vaudeville comedians at the end of their careers.

Paramount produced the biopic The Man Who Never Laughed in 1957 ( The Buster Keaton Story , written and directed by Sidney Sheldon ). Keaton was officially brought in as a consultant, but his objections were rarely heeded. The main actor Donald O'Connor also later distanced himself from the film, which partly depicts Keaton's life untrue. His own memories appeared in 1960 under the title My Wonderful World of Slapstick .

With the money that the film with his name brought him, Keaton bought a house - called by him "ranch" - in California, which he lived with his wife for the rest of his life. He had to give up his luxurious “Italian Villa” in Beverly Hills, which he owned at the height of his fame, in the 1930s. In 1952, James Mason, the new owner of the former Keaton villa, caused a surprise: Mason discovered long-forgotten copies of Keaton's classic films in a hidden storage room. Due to the chemical decay of the film material, which was previously based on flammable nitrocellulose, it was partially badly damaged.

The obsessive film collector Raymond Rohauer, whom Keaton met in 1954 at one of the reruns of The General , invested in saving the films. Under an agreement with Keaton is Rohauer secured the rights to the still existing classics and took over distribution to cinemas and festivals. In 1962 Rohauer organized sensational re-performances of the restored version of Der General in 20 cities in Germany, starting in Munich. Keaton, who accompanied the tour and had chosen the film, waited in front of the cinema during the screenings: he would never watch his own films with an audience.

In 1960, Keaton was awarded an Honorary Oscar for his contributions to film comedy.

The last films

As a living legend, he often resorted to his typical outfit from the silent film era for his film appearances . The Canadian short film The Railrodder (1965, screenplay and director: Gerald Potterton) pays homage to Keaton's silent films, but above all to the Canadian landscape. The documentary Buster Keaton Rides Again was made while filming The Railrodder . In addition to biographical stations, she gives insights into the personality and working methods of the aging Keaton.

In the same year, Samuel Beckett realized his experimental silent film film (directed by Alan Schneider) with Keaton in the lead role , which was invited to the Venice Film Festival . The premiere audience received the star guest Keaton for five minutes with a standing ovation .

The last cinema production was Keaton, directed by Richard Lester Toll, the old Romans did it (1966). At that time his health was already very poor, this time he was doubled during dangerous stunts. Still, he insisted on running his head against a tree.

For several years now, Keaton's health has deteriorated noticeably, which was sometimes expressed in severe coughing fits. The diagnosis of lung cancer , made at an advanced stage, was withheld from him by his wife and the doctor. Buster Keaton died at his home on February 1, 1966 at the age of 70 as a result of his illness.

It was only months later that the old Romans drove it to the cinemas. Less than a year after his death, the last premiere of a film with Keaton in a supporting role took place in the USA . He played a Nazi general in the American-Italian co-production War Italian Style , shot in 1965 . In the last scene, two marines release the captured general (Buster Keaton) and hand him civilian clothing that turns out to be the typical Buster outfit. With his baggy tailcoat and flat hat, he looks at the soldiers one last time, turns away from the camera and wanders away.

plant

Much of the films of the silent era have crumbled or lost, including some films Keaton made with Arbuckle. The films for which Keaton is responsible have been preserved, even if some only in badly damaged versions or in fragments. In the short films Hard Luck , Keaton's favorite film after an interview, and daydreams, entire sequences are missing . For the restored versions, they made do with still images to replace the missing scenes. A few moments are also missing in the short film The Convict , which leads to strong jumps within individual scenes in the restored version. The feature film Three Ages survived only in a visually damaged version, as it was only rediscovered in the 1950s and to this day the only negative was severely affected by the decomposition of the nitrocellulose. The same applies to the short film Water Has No Bars .

content

In the majority of his films, which were made during the period of his artistic independence, Keaton played the naive, clumsy young man - often a unworldly millionaire - who is rejected by his beloved wife because he apparently does not meet certain requirements. In Buster and the Police , she wants nothing to do with him until he's a successful businessman. In The General , his lover leaves him because he does not volunteer for military service like the other men. During the film he usually tries in vain to convince his lover of his qualities before he surpasses himself in the face of a major crisis. At the end of Der Musterschüler, for example, he saves his threatened loved one through top sporting performances, after failing miserably in all sports. In The Navigator he has to find his way as a spoiled millionaire on a huge, abandoned ship in the middle of the ocean and finally saves his lover from wild cannibals.

The romantic plot only provided the framework. Nothing inspired Keaton more in his cinematic work than technical devices and mechanized processes. Accordingly, both thematically and stylistically, they are the real focus of his stories and gags, such as steam locomotives in The General and Darn Hospitality , ships in The Navigator and Steamboat Bill, Jr. , or movie cameras and the cinema itself in The Cameraman and Sherlock, Jr. The short film The fully electric house is practically all about the dream of a fully mechanized household: the stairs turn into an escalator at the push of a button, the chairs at the dining table are moved by a switch, and the food is served from the kitchen directly to the dining table on a toy train. Admittedly, malfunctions soon turn the dream into a nightmare.

The theme of the chases , predestined for the cinema, is also an important part of Keaton's films. His complex and excitingly constructed sequences are among the classics of film history. As a prime example, consider the tumultuous car chase at the height of Sherlock, Jr. called: Sherlock jr. (Buster Keaton) flees from the gangsters first on foot, then as a passenger on a motorcycle - but without realizing that the driver has gone missing - and after a decidedly short interlude (the liberation of the girl) then with the gangster's automobile, who will soon be hot on his heels with another car. His film The General, which has been celebrated as a masterpiece, also largely consists of the chase of two steam locomotives. Other memorable variations of the persecution motif can be found prominently in Buster and the Police , Sieben Chances and The Cowboy : Here there are no vehicles, but an almost unmanageable mass of uniformed police officers, brides in wedding dresses, or cattle, from which Buster desperately has to flee.

style

Silent film comedians usually established certain hat models as trademarks. With the “pork pie hat”, Keaton created its own hat shape. A fedora served as the base , which he flattened just above the hat band. Keaton's quoted poker face (also known as “Stoneface”, “Deadpan” or “Frozen Face”) is also considered unique within the silent film era . Already trained during his childhood performances in Vaudeville, this remained his artistic trademark to the end. The only exception are some of his early films with Fatty Arbuckle, in which you can see a laughing Buster Keaton.

The comparison between his stoneface and the emotionless objects and machines with which he surrounds himself is obvious. But that still expression didn't mean that Keaton was blank as an actor. On the contrary, James Agee, in his article in Life Magazine, raved about Keaton's expressiveness for precisely this reason.

In addition to his distinctive, almost immobile facial features, Keaton is famous for his elaborate stunts , which make up a large part of his visual comedy: For example, his prat falls , slapstick-like falls, in which Keaton, as soon as his head hits the ground, practically around himself again itself swirls. This acrobatic style of bouncing is demonstrated and varied by Keaton in almost all of his comedies. When he switched to feature films, his stunts became more demanding and correspondingly risky. The cyclone sequence became legendary in Steamboat Bill, Jr. , while the facade of a house tilts on Buster and he is only saved by a small gable window, in whose recess he comes to stand. A deviation of Keaton by inches from the marked position would have had devastating consequences.

Not only in his often life-threatening stunts, but also in his gags, Keaton sometimes played openly with death, very clearly in the short film The Convict , his second publication: Buster is mistaken for a criminal sentenced to death. All fellow prisoners gather in the stands as if they were expecting an entertainment program. However, the gallows rope was secretly exchanged for an elastic rubber rope beforehand. When Buster falls through the trapdoor of the gallows with the noose around his neck, he swings up and down like a yo-yo a good dozen times . The perplexed guard turns to the angry inmates with an apology and promises, "To make up for that, we'll hang two of you tomorrow." Aside from this near-death humor, critics speak of an omnipresent melancholy that Keaton's films seem to exude.

In contrast to Chaplin, who liked to tell romantic love stories and deliberately staged women as idealized objects of longing, the women in Keaton's films are equal to the male hero. His approach to the subject of "romance" is emphatically dry and unsentimental, in some cases cynical. In Darn Hospitality , Buster sees a man beat and brutally abuse his wife. Courageously, he steps in between - and is indignantly pushed away by the woman, who then willingly allows her husband to abuse her again. Romance, it seems, is only for very naive souls. His short film In the Far North is a bit over the top : He has to watch his wife kiss another man in love. Theatrically, a tear rolls down his cheek; agitated, he shoots them both. Looking closely at the corpses, he realizes: It wasn't his wife - he was wrong about the house. Unlike Chaplin, Keaton only uses pathos for parody .

Keaton used and expanded the technical possibilities of the medium like no other of the great silent film comedians. Another pioneering achievement in this context is Der General : The majority of the film was shot with moving cameras. In addition, sophisticated trick technology was used in his films, the results of which are still surprising today, precisely because of the relatively primitive technology at the time. One of the most outstanding special effects sequences in film history can be found in Sherlock, Jr. : Buster enters the cinema screen from the auditorium. Due to a quick sequence of cuts, the environment changes constantly - from a house portal to desert, surf, snowy landscape to jungle with lions - and the buster caught in the film has to constantly adapt to these sudden changes.

It is significant, however, that Keaton only used such optical film tricks as they are used in In the Theater Amazing (Buster appears up to nine times in the same picture), only in exceptional cases for deception: They were mostly used where they were obviously tricks are. Authenticity was very important to him; the stunts should no doubt be perceived as as dangerous and real as they were. When a burning bridge was to collapse under the weight of a steam locomotive for Der General and drag the locomotive down with it, he decided not to use a model, as was common back then. Instead, he had a bridge built and it collapsed along with a real (albeit unoccupied) steam locomotive. Also the twelve-minute cyclone sequence in Steamboat Bill, Jr. was realized without cinematic tricks, but by means of a crane, elaborate backdrops and powerful aircraft engines.

Credibility was particularly important to him after switching to the full-length format for his comedies. His work shows a clear fault line here, as he was convinced that he could not bind the audience to a longer story if the gags would be too exaggerated. In his playful short films , which were consciously based on the aesthetics of the cartoon, there were far more animation effects to be seen than in his later full-length films, which focused on the drama of the framework. Especially his first narrative feature film Verflixte hospitality ( Three era before that was practical and stylistic of three short films) makes in the prologue the impression of an effective today melodrama . For Der Navigator he hired the drama-experienced director Donald Crisp . But when he got more and more enthusiastic about comic ideas and burlesque representation, Keaton separated from him and shot all the scenes seriously and under his own direction. Keaton: "I don't like over the top game."

Working method

Buster Keaton developed the stories and gags of his films in a simple but effective way: after a brilliant idea was found to start with, the team worked at the end - “... and when we had an ending that we were all happy with, then left we went back and worked out the middle section. For some reason the middle always came about by itself. "

Keaton's group behind the camera, some of which he had taken over from Arbuckle, included director Eddie Cline and the gagmen Jean Havez and Clyde Bruckman . Chief technician Fred Gabourie and cameraman Elgin Lessley took care of the much-noticed special effects . In front of the camera Joe Roberts , with his imposing stature a contrasting counterpart to the rather small Keaton, was the only regularly recurring actor in Keaton's films - until he died of a heart attack in 1923 after filming Verflixte Gastfreundschaft . But Keaton's father Joe was often seen in supporting roles.

The casting of the female lead was usually very straightforward. “If my studio manager could get a leading actress cheaply, he'd take her. He just didn't think they were important. ” Sybil Seely and Kathryn McGuire can often be seen as Keaton's partners . Well-known names like Phyllis Haver in the short film The Balloonatic are rare. However, Keaton was only dissatisfied with his partner in his first feature film Three Ages : He was shooting with a beauty queen who was not talented as an actor.

Since the plot and gags were discussed extensively in advance, the shooting always took place without a script. The team used, among other things, the city decorations that Chaplin - the previous owner of the studio - had erected on the studio premises. But Keaton also described outdoor shots in the city as extremely uncomplicated: both the police and the fire brigade or those responsible for the local railway line provided their help for the filming free of charge. Keaton bore the main responsibility as director, even if, for example, Eddie Cline is named as co-director in the opening credits.

With mostly good budgets and a lot of creativity, Keaton has developed sophisticated machines and devices for his many stunts , which made his daring jumps and other dangerous 'numbers' possible in the first place. So "[he] brought a piece of the world of artists onto the screen".

He realized his mostly technical gags with a lot of patience and dedication. In the short film Water Has No Bars (1921), for example, the ship built by Buster was supposed to sink into the water when it was launched. But despite all the precautions (a load of iron bars, holes in the bow, etc.) it did not slide as dead straight under the surface of the water as it corresponded to Keaton's idea of the strange timing. Keaton and his team worked for three days until the solution was found for the scene, which lasted only a few seconds: “[We] sink an anchor, of which we run a cable over a pulley at the stern of the ship, the other end is attached to a tug . We made all the air bubbles out of the boat, we made sure that there was enough water in the stern, and with the tug outside the picture we pulled the boat under the water. "

The filmed footage was arranged on shelves by film editor Sherman Kell according to scenes and takes. From this, Keaton assembled the film with his flair for timing . Thanks to his own studio with his permanent staff, Keaton was also able to improve finished films after test screenings with newly shot material without incurring high additional costs.

reception

At the beginning and also at the height of his career, Keaton was perceived positively as a successful, accomplished comedian, but his extraordinary style, linked to his "unmoved" facial expression, also met with irritation. Critics described his character as unemotional or even as a mechanical utensil to which the viewer - in contrast to other screen personalities such as Chaplins or Lloyds - could not develop a personal bond. Siegfried Kracauer said in 1926: “This slim, little man [...] has definitely lost his relationship with life. [...] The many objects: apparatus, tree trunks, tramway walls and human bodies throw him in the kettle, he no longer knows his way around, he has become apathetic under the senseless pressure of random things. "

The film critic and essayist Frieda Grafe describes the relationship to machines of some of the famous comedians in the silent film era as follows: “Chaplin gets helpless in their gears, Laurel and Hardy furiously defend themselves against them and demolish them; Buster Keaton masters it with serenity and insight; Bowers [meaning the silent filmmaker and actor Charles Bowers ] is not primarily their adversary, but a constructor who himself, [...], invents and builds the most insane apparatuses and lets loose on humanity. "

The portrayal of Keaton as a “machine man” has changed significantly over the decades: The poetic quality of his films occupies an important place in reviews. In his 1982 book The Moment of Silence, Robert Benayoun concentrates entirely on Keaton's visual expressiveness and draws parallels to surrealist works of art. By making technology the natural focus of his films, Keaton is also still regarded today as the silent film comedian of the present - in contrast to Chaplin, who more likely represents the Victorian era .

Even in the contemporary media, Chaplin and Keaton were often described as rivals, with Keaton, in the opinion of the critics, only narrowly defeated by Chaplin's mastery. Since Keaton's work was rediscovered by critics and the general public in the 1960s, there has been a tendency to place the importance of his films above that of Chaplin. The American critic Walter Kerr came to the conclusion in his highly acclaimed book The Silent Clowns in 1975 : “Let Chaplin be king and Keaton the jester. The king rules over everything, the fool tells the truth. [...] While others used the film to show themselves and their daring tricks, Keaton pointed in the opposite direction: to the essence of the film itself. "

The New York Review of Books (June 2011) has a comprehensive essay on Keaton, which includes many recent publications about him.

Jackie Chan , one of the most famous Asian action stars, describes Keaton as his greatest role model. Chan's typical martial arts interludes are an homage to Keaton's movements. The humor in his fights, like Keaton in his silent film era, incorporates objects from the surroundings and has become a trademark of Chan's.

Filmography

Short films with "Fatty" Arbuckle

- 1917: The Butcher Boy

- 1917: A Reckless Romeo

- 1917: The Rough House

- 1917: His Wedding Night

- 1917: Oh Doctor!

- 1917: Coney Island

- 1917: A Country Hero

- 1918: Out West

- 1918: The Bell Boy

- 1918: Moonshine

- 1918: Good Night, Nurse!

- 1918: The chef (The Cook)

- 1919: Back Stage

- 1919: The Hayseed

- 1920: The workshop (The Garage)

Short films Keaton Studio

- 1920: Buster Keaton fights the bloody hand (The High Sign)

- 1920: Honeymoon in a Prefabricated House (One Week)

- 1920: The Convict (Convict 13)

- 1920: Buster Keaton's wedding with obstacles ( The Scarecrow )

- 1920: Neighborhood in Klinch (Neighbors)

- 1921: The enchanted house (The Haunted House)

- 1921: Hard Luck

- 1921: The Goat (The Goat)

- 1921: In the theater (The Playhouse)

- 1921: Water has no beams (The Boat)

- 1922: The Paleface (The Paleface)

- 1922: Buster and the Police (Cops)

- 1922: My Wife's Relations

- 1922: The farrier (The Blacksmith)

- 1922: In the far north (The Frozen North)

- 1922: Daydreams

- 1922: The all-electric house (The Electric House)

- 1923: The Balloonatic / Survival Strategies

- 1923: An Adventurous Sea Voyage (The Love Nest)

Silent films

- 1920: The Saphead

- 1923: Three era (Three Ages)

- 1923: Darn hospitality (Our Hospitality)

- 1924: Sherlock, Jr. (Sherlock, Jr.)

- 1924: The Navigator (The Navigator)

- 1925: Seven Chances (Seven Chances)

- 1925: The Cowboy (Go West)

- 1926: The Alabama Killer (Battling Butler)

- 1926: The General (The General)

- 1927: The model student (college)

- 1928: Steamboat Bill, Jr. (Steamboat Bill Jr.)

- 1928: Buster Keaton, the film reporter (The Cameraman)

- 1929: Spite Marriage

- 1965: film (film) (short film)

Sound films (selection)

- 1930: Buster slips into film land (Free and Easy)

- 1931: We switch to Hollywood

- 1931: Casanova unwillingly (Parlor, Bedroom and Bath)

- 1932: Who doesn't love others (The Passionate Plumber)

- 1933: Have a beer! (What! No Beer?)

- 1934: Le Roi des Champs-Élysées

- 1934: Buster Keaton as a lifesaver (Allez Oop!) (Short film)

- 1935: La Fiesta de Santa Barbara

- 1935: Scandal in the Opera (A Night at the Opera) (only screenplay)

- 1939: The Marx Brothers in the Circus (At the Circus) (only screenplay)

- 1938: Too Hot to Handle (Too Hot to Handle) (only screenplay)

- 1939: Back in Hollywood (Hollywood Cavalcade)

- 1940: Li'l Abner

- 1940: Go West (script only)

- 1942: Six Fates (Tales of Manhattan) (co-script only)

- 1943: For ever and a day (Forever and a Day)

- 1944: San Diego I Love You

- 1948: The Superspy (A Southern Yankee) (screenplay only)

- 1949: Back in the summer (In the Good Old Summertime)

- 1949: The Lovable Cheat

- 1950: Sunset Boulevard (Sunset Boulevard)

- 1950: The Misadventures of Buster Keaton

- 1951: The Buster Keaton Show (TV show)

- 1951: Life with Buster Keaton (TV show)

- 1952: spotlight (Limelight)

- 1952: Paradise for Buster

- 1956: In 80 days around the world (Around the World in 80 Days)

- 1960: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn)

- 1963: It's a Mad, Mad, Mad , Mad World (It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World)

- 1964: Pajama Party (Pajama Party)

- 1965: The Railrodder

- 1966: A general and two more idiots (Due marines e un generale)

- 1966: The Scribe

- 1966: Funny Thing Happened on the ancient Romans (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum)

documentation

In 1987 film historians Kevin Brownlow and David Gill published the three-part documentary Buster Keaton: No Laughing! (Also: Buster Keaton - His life, his work ; Original title: Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow ). The television documentary, which lasts around 150 minutes, includes interviews with Buster Keaton from the archive, conversations with friends and former employees as well as his widow Eleanor. Thanks to its extensive material, it is one of the most informative portraits of Keaton's life and work.

In 2015, another documentary about Buster Keaton's career was made under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Péretié Buster Keaton How Hollywood broke a genius (original title: Buster Keaton Un génie brisé par Hollywood). On the occasion of the anniversary of his death 50 years ago, the French production was broadcast on Arte in early February 2016 .

literature

Overviews and introductions

- Wolfram Schütte , Peter W. Jansen : Buster Keaton. (= Film series. Vol. 3 = Hanser series. Vol. 182). Hanser, Munich et al. 1975, ISBN 3-446-12002-5 .

- Wolfram Tichy : Buster Keaton. With testimonials and photo documents . (= Rowohlt's monographs . 318). Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1983, ISBN 3-499-50318-2 .

- Julia Gerdes: [Article] Buster Keaton In: Thomas Koebner (Ed.): Film directors. Biographies, descriptions of works, filmographies. 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2008 [1. Ed. 1999], ISBN 978-3-15-010662-4 , pp. 378-383 [with references].

Others

- Robert Benayoun: Buster Keaton. The eye-gaze of silence . With a foreword by Louise Brooks . Bahia-Verlag, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-922699-18-9 .

- Tom Dardis: Buster Keaton. The Man Who Wouldn't Lie Down . University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis MI 2002, ISBN 0-8166-4001-7 .

- Marieluise Fleißer : A Portrait of Buster Keaton. In: Marlis Gerhardt (Ed.): Essays by famous women. From Else Lasker-Schüler to Christa Wolf (= Insel-Taschenbuch. It. Vol. 1941). Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1997, ISBN 3-458-33641-9 , pp. 309-312 (also in: Collected Works. Volume 2: Novel, narrative prose, essays (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch. Vol. 2275) Edited by Günther Rühle, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-518-38775-8 , p. 309 ff.).

- Eleanor Keaton, Jeffrey Vance: Buster Keaton Remembered . Abrams, New York NY 2001, ISBN 0-8109-4227-5 .

- Jim Kline: The Complete Films of Buster Keaton . Citadel Press, New York NY 1993, ISBN 0-8065-1303-9 .

- Dieter Krusche: Reclam's film guide . 13th, revised edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-010676-1 .

- Marion Meade: Buster Keaton. Cut to the chase. (A Biography) . HarperCollins, New York NY 1995, ISBN 0-06-017337-8 .

Web links

- Buster Keaton in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Buster Keaton in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Literature by and about Buster Keaton in the catalog of the German National Library

- Pictures by Buster Keaton In: Virtual History

- Buster Keaton photo gallery at silentgents.com

- Buster Keaton biography on "Who's Who"

- Buster Keaton Society at busterkeaton.com

- The Blacksmith, The Boat, The Paleface and Daydreams as bit torrent download

- The Playhouse, The Balloonatic, My Wifes Relations and The Electric House as bit torrent download

- Buster Keaton on Comedy and Making Movies , Columbia University

- Buster Keaton as a child performer (Univ. Of Washington / Sayre collection)

- ZeitZign : 02/01/1966 - anniversary of the death of actor Buster Keaton

References and comments

The main sources were the books The Complete Films of Buster Keaton by Jim Kline, Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase by Marion Meade and Pioneers of Films: From Silent Films to Hollywood by Kevin Brownlow, as well as the biography on the website of the International Buster-Keaton Gesellschaft and the Emmy Award-winning three-part television documentary Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill for Thames Television in association with Raymond Rohauer.

- ↑ See interview with Keaton in A Hard Act to Follow , Part 1, about 00:01.

- ↑ See Marion Meade: Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase. P. 62.

- ↑ See Kline, p. 13; see. Brownlow: pioneers of film. P. 551.

- ↑ Keaton on film work and Arbuckle: "I learned everything from him." - See Pioneers of Film , p. 557.

- ↑ Photoplay , May 1921, p. 53, quoted in Brownlow: Pioneers of the film. P. 552.

- ↑ Brownlow: Pioneers of Film. P. 546.

- ↑ “I knew before the camera was put up for the first scene that it was practically impossible to get a good motion picture.” (“Even before the camera was set up for the first scene, I knew that it was practically impossible to get a good one To produce film. ”) Keaton in a 1958 interview, cited in The Complete Films of Buster Keaton , p. 140.

- ^ "He's going to talk no matter what happens. You can't direct him any other way. "(" He talks and talks no matter what. You can't work with him in any other way. ") Keaton in an interview in 1958, quoted in The Complete Films of Buster Keaton , p. 142 .

- ↑ See interview with Keaton in A Hard Act to Follow , Part 3, about 00:09.

- ↑ See Kline: The Complete Films of Buster Keaton. P. 186 (with photo).

- ↑ "He was by his whole style and nature so much the most deeply" silent "of the silent comedians that even a smile was as deafeningly out of key as a yell. In a way his pictures are like a transcendent juggling act in which it seems that the whole universe is in exquisite flying motion and the one point of repose is the juggler's effortless, uninterested face. ”- James Agee in Life magazine , September 5, 1949 .

- ↑ See interviews with Rohauer and Eleanor Keaton in A Hard Act to Follow , Part 3.

- ↑ Standing ovations for 5 minutes (SZ-Magazin)

- ↑ See A Hard Act to Follow , Part 3.

- ↑ See Eleanor Keaton in A Hard Act to Follow , Part 3, about 00:46.

- ↑ See Margaret Meade, Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase , filmography in the appendix

- ↑ See Jim Kline: The Complete Films Of Buster Keaton and Gill / Brownlow: A Hard Act to Follow , Part 3.

- ↑ See Eleanor Keaton: Buster Keaton Remembered. P. 213.

- ^ "No other comedian could do as much with the dead-pan. He used this great, sad, motionless face to suggest various related things; a one track mind near the track's end of pure insanity; Mulish imperturbability under the wildest of circumstances; how dead a human being can get and still be alive; an awe-inspiring sort of patience and power to endure, proper to granite but uncanny in flesh and blood. "James Agee, Life , September 5, 1949

- ↑ Cf. Robert Benayoun: The moment of silence. Bahia Verlag, Munich, 1983, p. 92f.

- ^ Keaton, quoted in Brownlow: Pioneers of Film. P. 560.

- ↑ a b Keaton, quoted in Brownlow: Pioneers of Film. P. 534.

- ↑ "Before we started a film, everyone in the studio knew what it was about, so we didn't need anything in writing." - Keaton, quoted in Brownlow: Pioneers of Film. P. 534.

- ↑ “If we wanted to shoot in a densely populated area, we always notify the police. They then sent two or three traffic cops to regulate the traffic or help us in some other way. […] When we needed the fire brigade, they asked: 'What do you want?' We went and explained what we needed and when the call came they sent everything. It didn't cost us anything. No way. None of our railroad things have ever cost us anything. The Santa Fe line folks were proud when they saw SANTA FE on screen. ”- Keaton, quoted in Brownlow: Pioneers of Film. P. 532.

- ↑ Julia Gerdes: [Article] Buster Keaton In: Thomas Koebner (ed.): Film directors. Biographies, descriptions of works, filmographies. 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2008 [1. Ed. 1999], ISBN 978-3-15-010662-4 , pp. 378-383, here 383.

- ^ Keaton, quoted in Brownlow: Pioneers of Film . P. 556f.

- ↑ "I said, 'Give me the long shot of the ballroom.' He looked for that. 'Now give me the close-up of the butler announcing the arrival of his lordship.' While I cut this, he glues it together. He rolls it up as quickly as I hand it over to him. Back then with the nitrate film there was quite a risk of fire, but we didn't care. ”- Keaton quoted in Brownlow: Pioneers of Film . P. 555f.

- ↑ "If I want to have a sequence out - 'If I were to go left here on the street, we could leave out this whole part and start here again' - then in the afternoon we can take the cameras, go out on the street and do it rotate. That just costs the gasoline for our car and the footage […] And that adds up to about two dollars and thirty-nine cents. ”- Keaton, quoted in Brownlow: Pioneers of Film . P. 556.

- ↑ Quoted in Michael Hanisch: About them laugh (t) en millions. Henschelverlag, Berlin, 1976, p. 42.

- ↑ Grafe is quoted by Thomas Brandlmeier in Filmkomiker: Die Errettung des Grotesken , S. Fischer Verlag, 2017, subchapter: Bowers, Charley .

- ^ Walter Kerr: The Silent Clowns. DaCapo Press, 1990, p. 211.

- ↑ Jana Prikryl in New York Review of Books from June 2011: The Genius of Buster

- ↑ How Jackie Chan Draws Inspiration From Classic Hollywood . In: Mental Floss . ( mentalfloss.com [accessed January 2, 2017]).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Keaton, buster |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Keaton, Joseph Francis (real name); Keaton, Joseph Frank (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American actor, comedian and film director |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 4, 1895 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Piqua , Kansas , United States |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1st February 1966 |

| Place of death | Woodland Hills , California , United States |