Chilean War of Independence

| date | 1810-1826 |

|---|---|

| place | Chile |

| output | Chilean victory |

| consequences | Independence of Chile |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

José Miguel Carrera , Bernardo O'Higgins , Juan José Carrera , Luis Carrera , José de San Martín |

Antonio Pareja , Gabino Gaínza , Mariano Osorio

|

Rancagua - Chacabuco - Chalchuapa - Cancha Rayada - Maipú

The Chilean War of Independence was an armed conflict at the beginning of the 19th century between Chilean independence supporters on the one hand and the Spanish colonial rulers and Chilean royalists on the other. The war was part of the South American Wars of Independence and ended with Chile's independence from Spain.

The conflict began in September 1810 with the formation of a junta loyal to the Spanish monarchy as a transitional government, which disagreed with the new King of Spain appointed by Napoleon Bonaparte , Joseph Bonaparte , and awaited the return of Ferdinand VII to the Spanish throne. However, this also benefited the patriotic and extremist politicians who demanded major reforms and extensive independence and, over time, also used military means, with which the conflict as an independence movement spread to the whole country - and divided opinion among the population.

After an initial phase of liberal reforms, elections to a congress and already some, albeit loyal to the king, revolts from 1810 to 1814, known as Patria Vieja (Old Fatherland), the Spaniards - with a restored monarchy under Ferdinand VII Reconquista (recapture) between 1814 and 1817, before the Chilean independence leaders, with Argentine help, were finally able to liberate Chile from 1817 in the Patria Nueva (New Fatherland) until 1821 and 1826, respectively, but had to fight internal conflicts for a long time.

prehistory

The area of today's Chile had been developed as a colony of the Spanish Kingdom since the 16th century (→ History of Chile ). As General Capitanate Chile it belonged to the viceroyalty of Peru , but as a remote and poor part it was less in the focus of the colonial rulers than the areas of today's Peru or Colombia . Until his death in February 1808, the governor was the respected and popular Luis Muñoz de Guzmán . His successor was Francisco Antonio García Carrasco as the highest-ranking military man , who, however, had far less good contact with the local population than his predecessor.

Meanwhile, the situation in motherland Spain changed dramatically. In the war against the French troops of Napoleon Bonaparte (→ Napoleonic Wars on the Iberian Peninsula ), King Ferdinand lost the throne to Napoleon on May 6, 1808 and was imprisoned in Valençay . Napoleon declared his brother Joseph Bonaparte the new King of Spain. The Spanish forces loyal to the king formed the Junta Suprema Central and later the Assembly of Estates of the Cortes of Cádiz .

News of the war in Spain reached South America in August 1808. Ferdinand's sister Charlotte Joachime of Spain had fled to Rio de Janeiro with her family . Some of the royalists (the so-called Carlotistas ) saw her as the legitimate representative of the ruling family and wanted to transfer power in South America to her. In contrast, the Absolutistas took the view that only Ferdinand had the right to rule. Against the position of the royalists stood the juntistas , who wanted to form their own junta from local citizens to administer the country in the absence of a functioning and legitimate government.

In 1809, the Scorpion scandal moved the country: Governor García Carrasco and his secretary Juan Martínez de Rozas were involved in the attack on a smuggler 's ship and had saved the robbers and murderers from criminal consequences, with which they lost their last respect among the people.

In June 1810 news came from Europe that the French were besieging Cádiz, Spain . Garciá Carrasco, who represented the position of the Carlotistas , then took harsh measures against politically dissenters. This created unrest and on July 16, 1810, the hated governor was forced to abdicate. As the highest-ranking officer, Mateo de Toro Zambrano y Ureta, the first Creole born in the country, took over the office of governor. At that time he was already 82 years old. In Lima , the viceroy had already appointed Francisco Javier de Elío to succeed García Carrasco, but in Montevideo he was busy maintaining his position against the rebellious farmers on the Río de la Plata .

Toro Zambrano was pressured by the juntistas to transfer government power to a body. After some hesitation, he called a meeting at the town hall on September 18, 1810 at 9 o'clock to discuss the subject. This day is considered to be the beginning of Chilean independence efforts and is now Chilean national holiday .

The first junta

The juntistas quickly took over the helm at this meeting. With shouts of “We want a junta!” They stormed the stage. Toro Zambrano is said to have put his governor's baton on the table and handed over power with the words: "Here is the baton, take it and rule". It was decided to form a junta with the same powers as the previous governor. It was composed as follows:

| position | Surname |

|---|---|

| president | Mateo de Toro Zambrano y Ureta |

| Vice President | José Martínez de Aldunate |

| Members |

Fernando Marquez de la Plata Juan Martínez de Rozas Ignacio de la Carrera Colonel Francisco Javier de Reyna Juan Enrique Rosales |

| Secretaries |

José Gaspar Marín José Gregorio Argomedo |

The first official act was an oath of allegiance to King Ferdinand. After that, trade and customs issues were resolved, and a national congress was convened, whose 42 elected representatives were to meet in 1811. Eventually the junta decided to set up a militia to defend Chile.

The majority in the assembly was one of the moderates (Spanish: moderados ) under the leadership of José Miguel Infante . They only wanted a transitional government until King Ferdinand's return and were skeptical of reforms. The extremists (Spanish: extremistas or exaltados ), on the other hand, strived for greater independence from the motherland and extensive internal autonomy; their leader was Martínez de Rozas. Finally, there were the royalists (Spanish: realistas ) who wanted to keep the status quo and rejected any form of reform or self-government.

First Congress and Figueroa Revolt

By March 1811, the delegates for the Congress were elected. The elections gave the moderates a slight lead over the extremists, while the royalists were naturally beaten. In Concepción and Santiago de Chile the delegate elections were still pending when the royalist-minded Colonel Tomás de Figueroa undertook a revolt on April 1, 1811 , but it failed. Figueroa was executed and subsequently the Royal Court of Justice, the Real Audiencia of Chile , was dismissed for alleged complicity. In the elections that followed, the moderates won all six delegate seats for Santiago, but subsequently the rifts between moderates and extremists deepened, with the idea of a completely independent Chile gaining increasing support.

The Congress met for the first time on July 4, 1811. The composition of twelve delegates from Santiago instead of the originally planned six led to a dispute, as did the question of whether the country was obliged to pay financial contributions for the Spanish fight against Napoleon. Royalists and parts of the moderate supported this, while the extremists, pointing to the country's poverty, refused to pay.

The September coup of the Carreras

At this time (late July 1811) the young officer José Miguel Carrera returned from Spain to his homeland, joined the radical wing of the independence movement and quickly took over its leadership. Irregularities in the congressional elections were the trigger that Carrera and his brothers Juan José and Luis wanted to take power by coup. José initially sought a negotiated solution with the moderate forces, but could not achieve any success. On September 4, 1811, the Carreras put in a coup and tried to oust the royalists from Congress. The next day, independence-oriented representatives from Concepción replaced the previous MPs.

For example, the majority in Congress was forcibly shifted in favor of the extremists, but the plenary could not yet bring itself to a formal declaration of independence. Instead, the First Junta's vow of loyalty was reaffirmed . At the same time, a number of liberal reforms were initiated: First steps led to the abolition of slavery, freedom of trade and local self-government were strengthened, the salaries of state employees were cut and the representatives of the church were paid from taxpayers' money. The aim was to prevent the church from keeping itself from harming the people for its upkeep as before.

Second Carrera coup

Despite this progress in his favor, José Carrera undertook a second coup on November 15, 1811. As reasons, he cited that the composition did not correspond to the election result - although he himself had forced some seats to be replaced by force in September - and that the country was not yet ready for a separation of powers. Beyond that (but he only confided that to his diary) it was about a family rivalry between the Larraín family, whom he accused of dominating the Congress, and the Carreras. At the head of the state he placed a triumvirate made up of José Gaspar Marín , who had already belonged to the first junta - for Coquimbo, Bernardo O'Higgins - as a replacement for rival Rozas - for Concepción and himself for Santiago.

Two weeks later he dissolved the Congress. In protest, Marín and O'Higgins resigned from their posts and left Carrera absolute power. Under his leadership, the constitution of 1812 was drawn up , which formally recognized the supremacy of King Ferdinand, but was otherwise very liberal. In addition, Carrera created the first state symbols of Chile: a national flag and a coat of arms. The constitution guaranteed freedom of the press; Carrera had the first printing press brought to Chile, and under the direction of Camilo Henriquez , the first Chilean newspaper, Aurora de Chile, was created . In terms of foreign policy, Carrera established diplomatic relations with the United States , which brought Joel Roberts Poinsett, its first envoy (later: consul) to Chile.

Spanish offensive ("Reconquista")

Landing and train to Chillán

It was not until the beginning of 1813 that Viceroy José Fernando Abascal y Sousa attempted to restore the old conditions. He sent about 2,400 men under General Antonio Pareja to Chile, who allied on the island of Chiloé with local royalists, who formed the majority in the south of the country. Via Valdivia and Talcahuano the Spaniards reached Concepción, where they were received with applause. They moved to Chillán , which surrendered without a fight. The royalist army had now grown to 6,000 men.

Skirmish at Yerbas Buenas

On April 27, 1813 the first armed conflict with the Chileans broke out. In the village of Yerbas Buenas , near Linares , a group of around 600 Chileans under the command of Colonel Juan Dios de Puga attacked the royalist army under cover of darkness. The Chileans believed they were dealing with a scattered unit of the Spaniards, while the royalists, conversely, believed that the entire force of the Independence Army was attacking them. In the course of the fighting this misunderstanding was cleared up on both sides, the Chileans suffered great losses and withdrew to Talca .

Battle of Las Carlos and siege of Chillán

Carrera put the royalist troops at San Carlos on May 15, 1813 to fight. He and his men retained the upper hand (also thanks to their numerical superiority) and forced the Spaniards to retreat to Chillán , where they holed up. The Independence Army followed suit and began to besiege the city. The Spanish general, Antonio Pareja, died there on May 21st. Juan Francisco Sánchez temporarily took his place.

Carrera besieged the city in vain for weeks, but failed to take it. In addition to the bitter resistance, this was due to the Chileans' lack of equipment, but also to General Carrera's tactical weaknesses. The Spaniards were waiting for reinforcements, who arrived in October 1813 under the leadership of Gabino Gaínza .

El Roble's surprise

Carrera divided his army. He left a part under the command of his brother Juan José at the confluence of the Río Itata and Río Ñuble . The other part, about 800 men and artillery of 5 cannons, he led a few miles inland to El Roble under his own command. The royalists found out about this and set out that night under the orders of Juan Francisco Sánchez, where, with the support of local forces, they assembled a force of 1200 men. They surrounded the patriots and initially put them to flight at dawn on October 17, 1813. Carrera, fearful of being captured, fled through the Río Itata to reach the second Chilean army on the other side of the river.

Meanwhile, under Colonel Bernardo O'Higgins, a nest of resistance of around 200 men formed, which stood up to the Spaniards and finally managed to flee them after more than an hour. Carrera himself found words of appreciation for the heroic commitment of O'Higgins, whom he dubbed the first soldier (Spanish: primero soldado ) of his country. The royalists lost around 80 soldiers at El Roble, while 30 men were killed on the Chilean side.

His political opponents accused Carrera not only of his strategic and tactical mistakes, but above all of his flight in combat. Pressed on all sides, he was replaced at the beginning of 1814 by Bernardo O'Higgins as Commander in Chief. The affairs of state took over as Director Supremo the moderate Francisco de la Lastra .

Battle of Cancha Rayada

Meanwhile, the tide had turned in Europe. Through the Treaty of Valençay , Ferdinand VII came back to the Spanish throne and from 1814 he again claimed full sovereignty over the colonies in South America. The fighting in Chile dragged on: the Spaniards attacked the Chilean units under O'Higgins on March 19 and those under the command of Juan Mackenna on March 20, but were repulsed both times.

Under the command of Manuel Blanco Encalada , over 1,000 men had gathered in Santiago to recapture Talca from the Spanish. On March 29, 1814, they were surprised by a small royalist troop led by Chilean Angél Calvo and defeated within a quarter of an hour. A large part of the independence army escaped in the direction of Santiago, the royalists also took around 300 prisoners.

The Treaty of Lircay and the Battle of Las Tres Acequias

The general of the royalists was waiting for further reinforcements and used the time for peace negotiations, which took place under the mediation of the English Commodore James Hillyar in Santiago and resulted in the Treaty of Lircay in May 1814 . While the Chileans recognized the claim of the Spanish crown to the country and renounced their national symbols, in return the Spaniards granted them self-government through the incumbent government junta.

Neither the Spaniards nor the Chileans intended to keep their promises. The Spanish viceroy sent another expeditionary army under Mariano Osorio to the south of Chile. On the Chilean side, José Miguel Carrera came back to power in July 1814.

While the Spaniards marched on Santiago from the south, Carrera and O'Higgins sought a domestic political decision by military means. 1,600 men under Carrera met on the banks of the Río Maipo on the afternoon of August 26, 1814, the 700 men strong forces of O'Higgins. The Carreristas won.

The approach of the Spaniards led to the realization that one could only act together: O'Higgins granted Carrera the supreme command of the army and in return was appointed to the command of the second division. While José Carrera stayed in Santiago to fortify the city before the expected attack by the Spaniards, the rest of the Independence Army under Luis Carrera, Juan José Carrera and O'Higgins tried to hold back the advance as long as possible.

Battle of Rancagua

The Spanish troops of around 5,000 men took the offensive again and defeated the independence fighters, who were still weakened by the previous internal battles, in the first major confrontation on January 1st and 2nd. October 1814 at the Battle of Rancagua . The Carrera brothers wanted to place the Spaniards in the Angostura gorge, where, due to the nature of the terrain, they saw a favorable position to be able to hold on despite their numerical inferiority (the patriot army had shrunk to around 1,100 soldiers) and a rapid advance of the royalists on Santiago prevent.

But Bernardo O'Higgins made a fatal mistake and ordered his troops to go to the center of the city of Rancagua , where they were surrounded by royalists on October 2, 1814 and had to surrender at the end of the day. The Chileans speak of this battle as the disaster of Rancagua to this day . Many of the approximately 500 survivors were captured.

Spanish rule

Shortly afterwards, the Spaniards moved back to the capital Santiago de Chile . Bernardo O'Higgins and José Miguel Carrera fled with many other leaders of the independence movement to Argentina in the Mendoza region . The figureheads of the independence movement who remained in Chile, including Ignacio de la Carrera and several later presidents of Chile, were banished to the Juan Fernández Islands . The phase of the "old republic", as it is called today in Chile ( La Patria Vieja ), was over.

The viceroy first confirmed General Osorio as governor of Chile, but replaced him on December 26, 1815 by Casimiro Marcó del Pont , who proceeded with absolute severity against the independence strivings. A kind of police force called Las talaveras was specially set up for this purpose . The prosecutions under Vicente San Bruno were feared.

Guerrilla warfare

The Chilean leadership in exile in Argentina was divided. While O'Higgins allied himself with José de San Martín , the commander of the province of Mendoza, the Carrera brothers turned against him. You were executed in Mendoza for conspiracy. Only a few independence supporters under Manuel Rodríguez waged a kind of guerrilla war against the Spaniards. Even if the military successes of these actions remained modest, they strengthened the morale of the independence movement and made Rodríguez a popular hero.

Chilean-Argentinian successes

Andes crossing

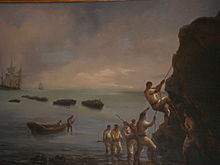

In Mendoza, the Chilean independence movement found support from José de San Martin . By the beginning of 1817 he gathered an army of around 4,000 Argentines and dispersed members of the Chilean troops. Although the Spaniards in Chile had about 8,000 men, San Martín decided to take the offensive. He set out on January 12, 1817 and crossed the Andes with 2,800 men, 1,600 horses and 12 artillery pieces, as well as over 9,000 mules . His move was later to be compared with Hannibal's crossing of the Alps ; on the way he lost a third of his men and half of the animals.

Battle of Chacabuco

The Spaniards had hurried north from Santiago with 1,500 men under the command of Brigadier Rafael Maroto to provide the Andean Army. Maroto changed his position to the south, but after consulting the governor he returned to Chacabuco. San Martín knew that the numerical superiority of the Chileans and Argentines would not last long and sought a quick decision. On February 12, 1817, he defeated the Spanish army at the Battle of Chacabuco and was able to enter Santiago two days later.

independence

The victorious San Martín was proclaimed Director Supremo in Santiago , but waived in favor of O'Higgins. On the first anniversary of the Battle of Chacabuco, he officially proclaimed the independence of Chile. This day marks the beginning of the "New Republic" ( Patria Nueva ) in Chile. In Lima, Joaquín de la Pezuela had already assumed his office as Viceroy of Peru on July 7, 1816 . Pezuela was the father-in-law of Mariano Osorio.

Victory of the Chileans

Second battle of Cancha Rayada

The Spanish associations had united in the south with Indian vigilantes from the Mapuche people . The royalists holed up in Talca, while the Chileans camped under San Martín on the plain of Cancha Rayada. Completely surprisingly, the Spaniards made a sortie on the evening of March 16, 1818 around half past seven in the evening and surprised the unpaved vanguard of the Andean Army. O'Higgins was wounded in the arm and the Chileans fled.

On March 21, the dispersed Chilean forces reunited in San Fernando . Meanwhile, news of the defeat reached the capital, Santiago. Rumors of O'Higgins' and San Martín's deaths made the rounds; a number of veterans of the War of Independence went on another exodus to Mendoza. The freedom hero Manuel Rodríguez managed to reassure the citizens of Santiago with his battle cry: “Citizens, we still have a fatherland!” (Spanish: “¡Aún tenemos Patria, ciudadanos!” ). Until O'Higgins arrived in Santiago, Rodríguez rose to Director Supremo for one day .

Battle of Maipu and retreat of the royalists to the south

Due to his wound, O'Higgins could no longer lead the command himself and handed over the command to José San Martín alone. On April 5, 1818, San Martín put the Spaniards in the hilly terrain in the battle of Maipú and defeated them in a six-hour battle. General Osorio fled and left the command of the royalists to Colonel José Ordóñez. 2,000 Spaniards fell and 3,000 were captured; the Andean Army lost about 1,000 men in battle.

After the catastrophic defeat in the Battle of Maipú, the Spaniards withdrew from central Chile to the southern port city of Valdivia and the island of Chiloé . Only after the Chileans had succeeded in creating a small fleet did they succeed in capturing these last Spanish bases. In 1820 a Chilean fleet under Thomas Cochrane conquered the heavily fortified Valdivia, and in 1826 Chiloé was also taken.

consequences

With the victory of the independence movement in 1817, the great return of the exiles from the Juan Fernández Islands began. Bernardo O'Higgins ruled Chile as president until 1823. At the same time, however, the conflict continued against the local royalists as Guerra a Muerte ("War to the Death"). The high point of this development was the Chilean Civil War from 1829 to 1833.

literature

- Diego Barros Arana : Historia Jeneral de la Independencia de Chile. 4 volumes, Imprenta del Ferrocarril, Santiago de Chile 1855.

- From Frobel: South American Wars of Freedom. In: Bernhard von Poten (Ed.): Concise dictionary of the entire military sciences. Volume 9, published by Velhagen & Glasing, Bielefeld and Leipzig 1880, pp. 97-101.

- Claudio Gay: Historia de la Independencia Chilena. 2 volumes, Thunot, Paris 1856.

- Robert Harvey: Liberators - South America's Savage Wars of Freedom 1810-1830. Robinson Publ., London 2002, ISBN 1-84119-623-1 .

- Gerhard Wunder : Principles of the War of Independence in Chile (1808–1823). Dissertation, Münster 1932.