Dazzle camouflage

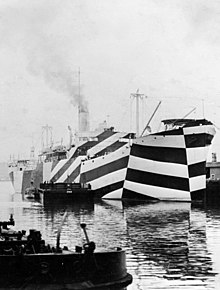

Dazzle camouflage , or dazzle painting , sometimes called razzle dazzle in the US , was a group of methods of painting ships (and other vehicles). The Royal Navy and the United States Navy used them particularly in World War I and, to a lesser extent, in World War II . This painting consisted of complex patterns of geometric shapes alternating in contrasting colors. The idea is credited to British marine painter Norman Wilkinson.

The term for this camouflage technique is derived from the English word "to dazzle" which means "dazzle or confuse" . The US term razzle dazzle ( "confusion/tumult" ) is at best colloquial in nature and does not appear in official documents of the US armed forces. The term may have been coined by journalists who refer to a so-called trick play of the same name from American football , in which the running back takes the ball and throws it to a receiver. The offense is trying to make the defense think it's a different play.

While forms of camouflage proper try to hide a target as much as possible, dazzle paint had a different purpose. It was intended to make it difficult for the enemy to determine a ship's (or other object's) size, direction, and speed. Norman Wilkinson explained in 1919 that the aim was to mislead the enemy about the course a ship was taking so that he would have a worse attacking position.

Dazzle was adopted by the Admiralty in Britain and then by the US Navy. Each ship painted in this way had a different, unique pattern. This made it impossible for the enemy to immediately identify the class of ship. Consequently, a large number of dazzle schemes were tried. Whether this coat of paint was successful is a matter of controversy. Because of the many factors that go into the evaluation, it is difficult to measure success.

Technological progress ended the discussion about Dazzle. Increasingly effective aerial reconnaissance and the development of radar technology made it easier for the enemy to locate and assess a ship.

development history

First try

In 1914, in a letter to Winston Churchill , the British zoologist John Graham Kerr proposed the use of a new camouflage technique for British warships in World War I and outlined what he believed to be the applicable principle of "dazzle camouflage". The aim is to "confuse - not hide" by dissolving the outlines of the ship. Kerr compared the effect to that produced by the patterns in a range of land animals, giraffes , zebras and jaguars . At first glance, Dazzle appeared to be a "suboptimal" form of camouflage, drawing attention to the ship rather than hiding it, especially in the context of the theater of operations. The approach emerged after Allied navies failed to develop reasonably effective means of making their ships invisible in all weather conditions.

Using the zebra example, Kerr suggested breaking up the vertical lines, such as ship's masts and funnels, with irregular white stripes. That would make the ships less conspicuous and "considerably increase the difficulty of determining an accurate distance ". It also minimizes the appearance of typical, recognizable shapes, making type determination difficult.

Kerr also suggested countershading in the same letter , which is the use of color to erase self-shading, thereby smoothing the appearance of solid, recognizable shapes. For example, he suggested painting the ship's artillery gray at the top and graduating to white at the bottom so that the guns would disappear against a gray background. He also suggested painting darker areas of the ship white and lighter areas gray, again with smooth gradations in between to make shapes and textures nearly invisible. By doing so, Kerr hoped to achieve a degree of "pure optical invisibility" as well as - particularly when measuring range - to confuse the enemy.

Whether because of this mixing of aims or the Admiralty's skepticism about "any theory based on animal analogies", the Admiralty claimed in July 1915 to have made "various experiments" and decided not to adopt Kerr's proposals, but to continue painting their ships in solid grey. Subsequent letters from Kerr did not change that decision.

Second attempt

Before Kerr, the American painter Abbott Handerson Thayer had developed a "theory of camouflage based on counter-shading and disruptive coloring," which he published in 1909 in the book Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom . In February 1915, Trayer saw an opportunity to realize his theoretical ideas and wrote a letter to Churchill. In it he suggested camouflage submarines like fish, for example mackerel . He also suggested painting ships white to make them "invisible". His ideas were considered by the Admiralty but rejected, along with Kerr's suggestions, as " freak methods of painting ships...of academic interest but of no practical use".

Third attempt

Norman Wilkinson, a naval painter and reserve officer in the Royal Navy, agreed with Kerr that the primary aim of dazzle painting was to confuse rather than conceal. However, he disagreed on how this confusion should be created. Wilkinson wanted to make it difficult for the enemy to judge a ship's type, size, speed, and course, thereby tricking enemy ship commanders into taking wrong or bad firing positions. It would be difficult for an observer to tell exactly whether the stern or the bow is in view; and accordingly it would be difficult to estimate whether the observed ship was moving towards or away from the observer's position.

Wilkinson's approach used a multitude of relatively large areas of strongly contrasting colors to mislead the enemy as to a ship's true course. Although the Dazzle camouflage could actually increase a ship's visibility in some lighting conditions or at close range, Wilkinson firmly believed that the conspicuous pattern obscured the outline of the ship's hull (admittedly not the superstructure), disguising the ship's correct course and it would make it harder to hit the ship.

decision

Ultimately, Wilkinson's idea was accepted by the Admiralty because of the urgent need for action given the state of the naval war at the time. Notably, Kerr's scientific approach, based on well-known methods of camouflage, disruptive coloring and counter-shading, was dropped in favor of Wilkinson's unscientific approach. Kerr's reasoning was clear, logical, and based on years of study, while Wilkinson's explanations, while simply structured and largely unsupported, were presented in an inspiring manner, based on the perceptions of a creative artist. Another decisive factor may have been that the decision-makers at the Admiralty felt more comfortable with the socially well-connected Wilkinson than with Kerr, who was described as “stubborn and pedantic”.

Wilkinson later claimed to have been unaware of Kerr and Thayer's zoology-based camouflage theories, claiming to have only heard of the "ancient invisibility idea" from Roman times. In it, Vegetius reports that "Venetian blue" (a bluish-green color like that of the sea) was used to camouflage ships during the Gallic Wars , when Julius Caesar sent his scouting ships to gather intelligence along the coast of Britain.

The RMS Mauretania , used as a troop transport in World War I.

The Canadian Empress of Russia during World War I (1918)

Desired mode of action and proof

Disturbance of the distance measurement

In 1973, Robert F. Sumrall, the curator of the US Naval Museum, in line with John Graham Kerr's 1914 reasoning, developed a theory that dazzle camouflage may actually have affected naval artillery coincidence ranging as intended by Wilkinson. The optical devices used for this had a mechanism, operated by a soldier, to calculate the distance. The soldier adjusted the mechanics until the two half-images of the intended target were aligned to form a complete image.

Dazzle, Sumrall argued, was meant to make this more difficult, since colliding patterns looked unusual even when the two halves were perfectly aligned. In the event that a submarine periscope actually contained such range finders, this could well be a determining factor. The patterns also sometimes included a false bow wave to make it difficult for the enemy to estimate the ship's speed.

Concealment of course and speed

Historian and TV presenter Sam Willis reasoned: Since Wilkinson knew that it was impossible to make a ship "invisible" with paint, the "extreme opposite" was Wilkinson's viable answer. Flashy shapes and stark color contrasts were designed to confuse enemy submarine commanders.

Willis showed that different mechanisms could have been used. For this he used as an example the camouflage schemes of the RMS Olympic , a sister ship of the RMS Titanic , which was used as a troop carrier HMT Olympic (Hired Military Transport ). According to them, the conflicting patterns on the ship's funnels may suggest that the ship is on a different course than Wilkinson had planned.

The curvature of the hull below the forward funnel could appear like a false bow wave and give a misleading impression of the ship's speed. The striped patterns at the bow and stern could create confusion as to "which end of the ship was which" (bow or stern).

That dazzle camouflage actually worked in this way is suggested by the statement of a German U-boat captain:

“It was only when it was half a mile away that I could tell it was one vessel (not several) steering a right angle, tacking starboard to port. The dark painted stripes on her rump made her stern appear like her bow, and a wide cut in green paint amidships looked like a water stain. The weather was clear and visibility good; it was the best camouflage I have ever seen.”

movement camouflage

In 2011, scientist Nicholas E. Scott-Samuel and colleagues presented evidence that human perception of speed is distorted by a dazzle paint, using the calculation of motion patterns on a computer. However, the speeds required for "motion camouflage" (English: Motion Dazzle ) are much higher than for ships of the First World War. Scott-Samuel noted that the targets in the experiment corresponded to a Dazzle-painted Land Rover at a distance of 70 m and moving at 90 km/h.

If a target so cloaked causes a seven percent misjudgment of observed velocity, a recoilless handheld antitank weapon that travels that distance in about half a second would hit 90 cm from the intended aiming point, or 7% of the distance traveled by the target. That could be enough to prevent serious personal injury in the dazzle camouflage vehicle, or possibly cause the missile to miss the target entirely.

Experiments with airplanes

During World War I, the Royal Flying Corps conducted experiments on British aircraft such as the Sopwith Camel . It should be made more difficult for an opposing shooter to judge the angle of attack and flight direction. Similarly, the Royal Navy painted some of their Felixstowe flying boats with dazzle lines resembling those on their ships' camouflage. The effect remained doubtful, but it was noted that the number of machines under fire from friendly anti-aircraft gunners had decreased.

Another attempt was made by the US Navy in its Naval Aviation Department during World War II (circa 1940) to use Dazzle. The painter and illustrator McClelland Barclay developed several patterns for US Navy aircraft such as the Douglas TBD or the Brewster F2A . Again, the main goal was not to "hide the object" but to try to "confuse the enemy and make it difficult for them to assess the plane's shape and position." The Dazzle-cloaked planes even performed combat missions, but the effect proved as unsatisfactory.

evaluation

The effectiveness of dazzle camouflage was disputed during World War I, but it was adopted by both Britain and the United States nonetheless. In 1918, the British Admiralty analyzed their ship losses, but did not come to a clear conclusion.

Ships with Dazzle were attacked on 1.47% of their trips, as opposed to 1.12% of the uncloaked ships, which first of all indicates increased visibility. However, Wilkinson had pointed out from the start that the dazzle coating was not trying to make the ships more difficult to see, but to make their accurate registration (course and calculation) more difficult.

The picture that emerged was that of the ships hit and sunk by torpedoes, 43% had dazzle paint versus 54% with no camouflage. 41% of ships with Dazzle were hit amidships , compared to 52% of those without.

These different parameters might suggest that U-boat commanders had more difficulty deciding where a ship was going and where to aim. In addition, the ships painted in Dazzle Camouflage were larger than the uncloaked ships, 38% of them were over 5000 tons compared to only 13% of the uncloaked ships, making the comparisons quite unreliable.

In hindsight, too many factors (choice of color scheme, size and speed of ships, tactics used) went into the analysis to be sure which factors were significant or which schemes produced the best results. Abbott Handerson Thayer also carried out an experiment on dazzle camouflage , which, however, did not show any clearly verifiable advantage over a simple gray paint finish.

The US data was analyzed by Harold Van Buskirk in 1919: 1256 ships were camouflaged with Dazzle between March 1, 1918 and the end of the war on November 11 of the same year. Among American merchant ships of 2,500 tons or more, 78 uncamouflaged ships were sunk versus only 18 camouflaged ships; of these 18, 11 were sunk by torpedoes, 4 by collisions and 3 by mines. No US Navy ship (all camouflaged) was sunk during the same period. So Buskirk claimed that less than 1 percent of US merchant ships so painted were lost. However, without knowing the exact number of ships not painted in Dazzle fashion, it is not possible to calculate loss rates for comparison.

Dazzle in art

The abstract patterns of the Dazzle camouflage attracted the attention of artists such as Picasso , who claimed that cubists like himself invented it. In a conversation with Gertrude Stein , shortly after seeing a cannon camouflaged with Dazzle rolling through the streets of Paris for the first time, he declared: "Yes, we did it, THIS is Cubism."

In Britain, Edward Wadsworth , who was responsible for camouflage painting over 2000 ships during the war, created a series of paintings based on his Dazzle designs after the war. Arthur Lismer, a Canadian painter who belonged to the Group of Seven , also explored the subject, as in the 1918 painting Halifax Harbor . In America, Burnell Poole made several paintings of United States Navy ships in dazzle camouflage at sea . Science journalist Peter Forbes, among others, noted in his book Dazzled and Deceived that the ships had a modernist appearance and their designs could qualify as avant-garde or vorticist art.[17]

In 2007, the history of the development of the Dazzle camouflage was presented in detail as part of the Imperial War Museum 's "The Art of Camouflage" exhibition.

In 2009, the US Naval Library at the Rhode Island School of Design displayed their rediscovered collection of lithographic print plans of the paintwork of American World War I merchant ships in an exhibition entitled "Bedazzled".

In 2014 the Centenary Art Commission supported three art installations in the UK: Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez provided the pilot ship MV Edmund Gardner with a very colorful dazzle camouflage as part of the 2014 Liverpool Biennial. British pop artist Peter Blake was commissioned to create an exterior livery for the MV Snowdrop , which he dubbed Everybody Razzle Dazzle , in which he combined his recurring elements (stars, targets, etc.) with WW1 dazzle designs . German sculptor Tobias Rehberger redesigned HMS President , briefly dazzled (among other names) as early as World War I and moored at Blackfriars Bridge in London since 1922, to commemorate the Dazzle era a century later .

Camouflaged ships in dry dock by E. Wadsworth (1918) as a woodcut

web links

- www.history.com Article on the development of Dazzle Camouflage . Retrieved November 28, 2021 (English)

- Why ships used this camouflage in World War I Video on the history and operation of Dazzle camouflage . On YouTube . Retrieved November 28, 2021 (English)

- Dazzle Camouflage: Hiding in Plain Sight Exhibition Report on an exhibition dealing with the topic. On Youtube. Retrieved November 28, 2021 (English)

supporting documents

- ↑ razzle-dazzle - LEO: Translation in the English ⇔ German dictionary. Retrieved December 21, 2021 .

- ↑ dazzle camouflage - National Archives Search Results. Retrieved December 21, 2021 .

- ↑ razzle dazzle camouflage - National Archives Search Results. Retrieved December 21, 2021 .

- ↑ https://www.cnrs-scrn.org/northern_mariner/vol19/tnm_19_171-192.pdf

- ↑ a b c d e f Forbes, Peter (2009). Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage . Yale University Press. pages 87-89. ISBN 978-0-300-17896-8 .

- ↑ Patrick Wright: Cubist Slugs . In: London Review of Books . tape 27 , No. 12 , 2005 June 23, ISSN 0260-9592 ( lrb.co.uk [accessed 22 November 2021]).

- ↑ Theodore Roosevelt, Gerald Handerson Thayer, Abbott Handerson Thayer: Revealing and concealing coloration in birds and mammals. Bulletin of the AMNH ; v. 30, article 8. 1911 ( amnh.org [accessed 22 November 2021]).

- ↑ a b Michael Glover "Now you see it... Now you don't". 10 March 2007. The Times

- ↑ a b c Tim Newark, Camouflage . Thames and Hudson / Imperial War Museum (2007). page 74.

- ↑ a b c Forbes, Peter (2009). Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage . Yale University Press. pages 90 – 91. ISBN 978-0-300-17896-8 .

- ↑ Forbes, Peter (2009). Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage . Yale University Press. Page 97. ISBN 978-0-300-17896-8 .

- ↑ ab Forbes , Peter (2009). Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage . Yale University Press. Page 96. ISBN 978-0-300-17896-8 .

- ↑ ab Forbes , Peter (2009). Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage . Yale University Press. Pages 89 – 100. ISBN 978-0-300-17896-8 .

- ↑ Forbes, Peter (2009). Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage . Yale University Press. Page 92. ISBN 978-0-300-17896-8 .

- ↑ Robert Cushman Murphy . "Navy camouflage". The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly . Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (January 1917). Page 35 – 39.

- ↑ a b WW1: How did an artist help Britain fight the war at sea? Retrieved November 28, 2021 (English).

- ↑ Newark, Tim (2007). camouflage . Thames and Hudson / Imperial War Museum. page 74.

- ↑ Nicholas E Scott-Samuel, Roland Baddeley, Chloe E Palmer, Innes C Cuthill: Dazzle Camouflage Affects Speed Perception . In: PLoSONE . Volume 6, No. 6, 1 June 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3105982/

- ↑ Imperial War Museum: CAMOUFLAGE DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR. Retrieved November 24, 2021 (English).

- ↑ Nick D'Alto: Inventing the Invisible Airplane. Retrieved November 24, 2021 (English).

- ↑ Ann Elijah. Camouflage Australia: Art, nature, science and war . Sydney University Press. (2011). pages 186-188. ISBN 978-1-920899-73-8 .

- ↑ The Art of McClelland Barclay. March 13, 2015, retrieved November 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Hartcup, Guy (1979). Camouflage: the history of concealment and deception in war . Pen & Sword.

- ↑ Scott-Samuel, Nicholas E; Baddeley, Roland; Palmer, Chloe E; Cuthill, Innes C (June 2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3105982/

- ↑ Martin Stevens, Daniella H Yule, Graeme D Ruxton: Dazzle coloration and prey movement . In: Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences . Vol. 275, No. 1651, 22 November 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2605810/

- ↑ Buskirk, Harold Van (1919). "Camouflage". Transactions of the Illuminating Engineering Society . 14 (5): pages 225-229. https://web.archive.org/web/20160304053850/http://www.forgottenbooks.com/readbook_text/Illuminating_Engineering_v14_1000185898/421

- ↑ Campbell-Johnson, Rachel: Camouflage at IWM . TheTimes. March 21, 2007.

- ↑ Marter, Joan M.: The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art , Oxford University Press, 2011, Vol. 1, p. 401.

- ↑ Saunders, Nicholas J.; Cornish, Paul. (ed.): Contested Objects: Material Memories of the Great War , Routledge, 2014. Jonathan Black: "'A few broad stripes': Perception, Deception, and the 'Dazzle Ship' phenomenon of the First World War.", p .190-202.

- ↑ Sir Henry John Newbolt , Submarine and Anti-Submarine , Longmans, Green and Co, 1919. P. 46. "You look long and hard at this dazzle-ship. She doesn't give you any sensation of being dazzled; but she is, in some queer way, all wrong".

- ↑ Deer, Patrick: Culture in Camouflage: War, Empire, and Modern British Literature . Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 46.

- ↑ https://www.gallery.ca/whats-on/exhibitions-and-galleries/masterpiece-in-focus-halifax-harbour-1918

- ↑ "A Fast Convoy" by Burnell Poole. Retrieved November 25, 2021 (US English).

- ↑ Peter Forbes, Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage . Ed.: Yale University Press. 2011, ISBN 0-300-17896-4 .

- ↑ Newark, Tim (2007). camouflage . Thames & Hudson with Imperial War Museum. pp. Inside cover.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20111116220642/http://dazzle.risd.edu/

- ↑ DAZZLE SHIPS - 14-18 NOW. 9 October 2014, retrieved 25 November 2021 .

- ↑ Geographer:: Dazzle Ship, Canning Graving Dock © David Dixon. Retrieved November 25, 2021 (English).

- ↑ Catherine Jones: VIDEO: Razzle Dazzle Mersey Ferry unveiled by Sir Peter Blake. 2 April 2015, accessed 25 November 2021 (English).

- ↑ First world war dazzle painting revived on ships in Liverpool and London. 14 July 2014, accessed 25 November 2021 (English).