The origin of the world (comic)

| Comic | |

|---|---|

| title | The origin of the world |

| Original title | Kunskapens frukt |

| country | Sweden |

| author | Liv Strömquist |

| publishing company | Ordfront Förlag |

| First publication | 2014 |

| expenditure | 1 |

The Origin of the World ( Swedish Kunskapens frukt ) is a feminist comic by Liv Strömquist , which was published in 2014 by Ordfront Förlag. The German translation was published by avant-Verlag in 2017. In her work, Strömquist traces the cultural history of the vulva . The non-fiction comic is an international success and has been translated into numerous languages. Excerpts from the work have been exhibited several times, with the representation of menstruating women in particular causing controversial debates. The origin of the world represents an important feminist contribution not only in the comic medium, but also in scientific discourse.

Concept and content

Liv Strömquist had initially dealt with the topic of menstruation because she had severe menstrual pain as a teenager , and even passed out in school, but was too embarrassed to tell anyone. Her research expanded to include the female sex organ. In five chapters, Strömquist analyzes the historical construction and taboo of the vulva. The non-fiction comic does not follow a central plot, but rather the individual episodes in the form of graphic essays focus on topics. As an introduction before the first chapter heading, Strömquist greets her readers almost in surprise and casually. The figure addresses its audience directly, while standing in a white semicircle in front of an otherwise black background, and introduces the first chapter of her work. The content of the individual chapters is briefly presented below.

Chapter 1 - Men who are too interested in what is called "the female genital organ" (p. 7) : In the first chapter, Strömquist names seven negative examples of men who have dealt with the female genital organ. These include John Harvey Kellogg , who treated female masturbation by applying carbolic acid to the clitoris , and witch trials in which "strange teats" in "secret places" served as evidence. The chapter closes with a group of Swedish scientists who exhumed the remains of Queen Christina of Sweden in 1965 in order to examine them for traces of hermaphroditism .

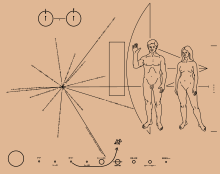

Chapter 2 - Upside down cockscomb (p. 31) : Strömquist answers the question of what the female sexual organ is and explains, for example, the difference between vulva and vagina . She points out that the two terms are mostly used as synonyms, which is wrong. She also takes a critical look at the handling and representation of the female sexual organs. When NASA launched the Pioneer 10 spacecraft in 1972 , it contained schematic representations of human anatomy. Leading NASA scientist John E. Naugle reduced the level of detail in the drawing by removing a line in the crotch of the representation of the woman. In addition, according to Strömquist, the external sexual organs of women in particular are linguistically excluded in numerous social aspects. Far too often these are circumscribed by paraphrases and metaphors instead of clearly naming the vulva, for example.

Chapter 3 - OK !!! Now comes a comic about orgasm. AAHHAA (p. 56) : This chapter begins with quotes in which the female orgasm is described as secondary and almost insignificant ("[f] ure for some women sex is not necessarily synonymous with orgasm, since other things are more important to them" or "[t] he woman may not want to orgasm with every sexual act"). As elsewhere, Strömquist swaps roles to emphasize the different valuation between women and men. The author also makes the point that the female orgasm is always defined in relation to male sexuality. The female sexuality is sometimes described as a worse version, sometimes as the opposite of the man, but never as something of its own.

Chapter 4 - Feeling Eve or In Search of Mama's Garden (p. 83) : The essay deals with the subject of shame , starting with the difference between shame that relates to something that defines yourself and guilt that you feel about something feel that one has done. For this purpose, the author puts short anecdotes from various women into the mouth of the biblical figure Eva . Among them are, for example, a young girl who is ashamed of her first period and tries to hide it ("What I remember best is that my stomach hurt terribly. Not because I had period pain, but because of fear."), or women who are ashamed of or even disgusted with their own sexual organs. In another quote, a woman reported sexual harassment , which she did not tell anyone because she was too embarrassed.

Chapter 5 - Blood Mountain (p. 99) : The last chapter of the non-fiction comic deals in detail with the menstruation of women. Strömquist deals with cultural, social and religious influences on the perception and handling of the topic and emphasizes above all the current taboo and lack of publicity. The comic artist, for example, makes the tampon industry the subject of her analysis and attests to it an “obsession” with terms such as “fresh” and “safe”. It also addresses the cultural change, starting from the Stone Age or Antiquity , when menstruation was considered a symbol of fertility and was often depicted in art and culture. Some pages of the final essay deal with premenstrual syndrome .

style

The author complements her own simple drawings with numerous photos and historical images. Except for the fourth chapter, Feeling Eve or In Search of Mama's Garden , The Origin of the World is kept in black and white. Strömquist also pursues a pedagogical approach with her work and repeatedly inserts footnotes and evidence from scientific literature into images and text. The footnotes deliberately interrupt the sequence of text and drawings in order, for example, to contextualize the historical background more precisely. Swedish critics describe the work as a gender study in comic form (“genusvetenskap i serieform”). In mostly uniformly arranged panels, Strömquist presents the facts and results of her research and also takes a personal position on the content, for example when she criticizes social behavior and the tabooing of menstruation. The entertaining medium of comics takes a back seat, for example the large amount of facts is clearly structured and presented with the help of the panels. The caricature-like to childish appearing drawings are more illustrative than content. For example, the last chapter is completely black and white, only the color red is used in strong contrast. In two almost identical panels, the scene and perception of it changes due to a changed detail: The red spot on the sofa between the woman's legs is created once by a slipped sanitary napkin , in the second scene by an overturned glass of red wine. The dynamic typeface, through which Strömquist brings humor and tempo into her narrative, is more varied. For example, the author uses a large, heavy font to put a loud punchline after turning the page. Elsewhere the impression arises that Strömquist is talking himself in rage for pages in lower case letters. The artist herself appears as a character in her comic and guides through a large part of her work as a sharp-tongued moderator and critical commentator. The author repeatedly swaps roles between women and men in order to clarify the differences in how society is viewed and judged. In the third essay, for example, she has a male figure ask whether it is important to have an orgasm. Strömquist cites the work of the Canadian comic artist Julie Doucet as an important influence and reference point for The Origin of the World .

Analyzes

The origin of the world makes an outstanding contribution to feminism and gender issues, especially in the comic medium . The comic also shows itself to be relevant for the ongoing discussion in a scientific context. Since Strömquist consciously interrupts her narrative in Der Ursprung der Welt with academic references (“metatextual interruptions that break up the flow”), the work can be classified as a self-reflective comic or a “meta-comic” (“self-reflective comics "Or" metacomics "). The break in the flow of reading directs attention to the medium of comics itself. This gives readers the opportunity to question the status of the text and the media context of the work. At the same time, however, attention is diverted from the actual content, which is particularly contrary to the pedagogical approach.

The word “frukt” (Swedish for “fruit”) in the title of the original edition can be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, the word is associated with the successful result of (hard) work, on the other hand, the clearer allusion to the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge . That is why the title Kunskapens frukt (Swedish for "The Fruit of Knowledge") also refers to the gain of sexual knowledge with a double meaning: firstly in the sense of decades of studies and the increase in knowledge about female sexuality within patriarchal cultures and secondly as an archive of social oppression and delegitimization of Women.

There are numerous approaches and ways of organizing genders in different societies. It was not until the 19th century that an obsession arose with the scientific classification of sexual organs (“royal organ”) as “normal” or “abnormal” (“avvikande”). This distinction also resulted in an expansion of disciplinary power (“biopower”). The gender problem manifests itself not only in the stigmatization of the female body, but also in the way knowledge is reproduced within the discourse that is too focused on the objects and their definition. A scene in the first chapter of The Origin of the World shows two surgeons operating to change the sex of intersex infants , which in this context is to be understood as a show of power. Through the influence of the sexologist John Money , who supported a binary gender system, the view prevailed that intersex infants should be operated on as early as possible in order to adapt the child's gender to the binary categorization. At the same time as the operation, the two doctors talk. Not only do they comment on their own actions during the procedure, but they also address feminist theories and refer to “biopower”. By juxtaposing the cold, expressionless exercise of power and the critical examination of the subject, Strömquist creates a scene full of dry irony. In doing so, it leaves open whether the actors cannot or do not want to stop their actions, for example because they have lost sight of the scope of the surgical intervention. Strömquist comments on the scene with the words, among other things, "For the doctors, making a pussy meant a kind of relaxation exercise during working hours, like other people Facebook".

The last page of the first chapter, Men who are too interested in what is called "the female reproductive organ", shows a historical account of Queen Christina of Sweden. The Italian engraving from the 17th century shows Queen Christina after her abdication, on horseback and in masculine clothing, she enters Rome . Strömquist places a speech bubble over the historical representation with the text "Fuck off forever" ("Fuck off för evigt"). The text can be interpreted as an articulated resistance to the scientific and cultural interests regarding the classification and classification of body types, which are particularly dominated by a binary representation of sex and gender. The use of the image also shows an example of the approach and attempt to reclaim historical figures for feminism and queer theories .

The last chapter Blood Mountain deals with menstruation and especially the current taboo. In the academic context, Der Ursprung der Welt represents a contemporary contribution that builds on previous activism and feminist criticism. Strömquist's comic or her chapter Blood Mountain is described, among other things, as “contemporary menstrual activism”. This form of activism criticizes not only the lack of visibility and publicity of menstruation, especially driven by the hygiene products industry, but also the binary definition of menstruating bodies as “different”. Since not all and not only women menstruate, The Origin of the World can also be understood as queer activism. On June 24, 2013, Strömquist designed and moderated the radio report Sommar i P1 (Swedish for "Summer in P1"), which is why the topic of menstruation was gaining increasing attention in Sweden. There was even talk of a menstrual revolution in various genres of art . In 2014, Kvinnor ritar bara serier om mens (Swedish for “women only draw comics about menstruation”) was another comic on the same subject. The anthology collects various contributions that depict menstruation in different styles and perspectives, including from trans men . The title of the comic anthology goes back to a quote from Strömquist that the comic artist made at Sommar i P1 : A male colleague told Strömquist that comics by women are not worth reading because they only deal with menstruation.

Publications and sales success

Kunskapens frukt was published by Ordfront Förlag in 2014 . Around 40,000 copies of the original Swedish edition had been sold by 2018. The German translation by Katharina Erben was published by avant-verlag in 2017. The German editions of Strömquist published by avant-verlag were funded by the Swedish Kulturrådet (Swedish for “Kulturrat”) with 5000 Swedish kronor , which is around 500 euros corresponds to. The financially supported translations include, for example, The Origin of the World and The Origin of Love . The title of the German edition is based on the painting The Origin of the World ( French: L'Origine du monde ) by Gustave Courbet . The cover of the German and Swedish original editions shows a photo of the comic author, who is sitting on a small wooden bench with her legs spread apart and her hands forming a triangle in her crotch. On the bench next to Strömquist, a submachine gun leans against the white wall in the background. The cover design is an allusion to the “Genitalpanik” campaign by the artist Valie Export in 1968. Due to the continued sales success of The Origin of the World , earlier books by the author have also been translated into German. In 2020, The Origin of the World was still the biggest sales success of avant-Verlag. In February 2021, the non-fiction comic took second place on Buchreport's bestseller list on the subject of "Graphic Novel" . In 2018, avant-Verlag brought out the comic albums The Origin of the World and The Origin of Love , initially published individually, together in a hardcover edition.

- Kunskapens frukt. Ordfront Förlag, Stockholm 2014, Danskt Volume (softcover with flaps), 139 pages, ISBN 978-91-7037-804-1 .

- The origin of the world. Avant-verlag, Berlin 2017, softcover, 140 pages, ISBN 978-3-945034-56-9 .

- The origin of the world & the origin of love. Avant-verlag, Berlin 2018, hardcover with linen spine, 280 pages, ISBN 978-3-96445-003-6 .

Rackham published the French edition L'origine du monde in 2016 ( ISBN 978-2-87827-197-3 ). On the cover you can see a drawing from the fourth chapter Feeling Eve or In Search of Mama's Garden . The motif shows the biblical figure Eve together with the snake from the Garden of Eden . With Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. The Patriarchy , Strömquist's first comic was published in English in 2018. In the USA, Fantagraphics Books published the comic ( ISBN 978-1-68396-110-9 ), the British edition published Virago Press ( ISBN 978-0-349-01073-1 ). The same photo of the artist can be seen on the cover of the US and UK publication, but the submachine gun has been removed from the illustration. There are other translations into Bulgarian, Danish, Finnish, Italian, Japanese, Croatian, Dutch, Filipino, Portuguese, Russian, Slovenian, Spanish, Czech and Ukrainian.

Exhibitions

At the end of 2014 the Landskrona Museum showed enlarged excerpts and pictures from the fourth chapter Blood Mountain . From 2017 to 2019, a total of 26 pictures by Strömquist under the title "The Night Garden" were on view in the Slussen subway station in Stockholm . In addition to drawings from Der Ursprung der Welt , contributions from earlier works by the artist and exclusive illustrations for the installation were also on display. In addition to depictions of plants and animals, three illustrations of menstruating women were shown, including a figure skater from The Origin of the World . In particular, the clearly visible depiction of menstruating women triggered different reactions among the commuters, which became known primarily through social media : some found the images to be funny or successfully provocative, others saw the depictions as a shocking breach of a taboo . A central point of criticism revolved around the question of whether a public bus stop represents an appropriate exhibition framework for such topics. The Stockholm local transport company Storstockholms Lokaltrafik received around 30 formal complaints about the exhibition. Almost all concerns were related to the menstruating characters and were mainly voiced by men. The right-wing populist party Sverigedemokraterna (Swedish for "The Sweden Democrats") unsuccessfully campaigned for an early end to the publicly funded installation. Based on her experience, the different reactions came as no surprise to Strömquist and she therefore assessed the debate that was initiated as important overall and beneficial to the topic.

Pictures and excerpts from Strömquist's The Origin of the World were also exhibited outside of her home country, Sweden . From August to October 2016, the artist's drawings were on view at the Institut Suédois in Paris as part of the “Le Divan de Liv” exhibition. The organizer presented the contributions from The Origin of the World , the French translation of which was published about a month before the start of the exhibition, in a separate exhibition room. Among other things, excerpts from the first chapter were shown men who are too interested in what is called “the female sexual organ” , such as Sigmund Freud and John Harvey Kellogg, or depictions of menstruating characters from the fifth chapter Blood Mountain . As part of the Nordwind Festival 2019 in Hamburg , an exhibition in the Kampnagel cultural center was dedicated to Strömquist . In addition to drawings from The Origin of the World , reprints from the comics The Origin of Love and I'm Every Woman were on view.

Adaptations

In the theater Ballhof in Hannover was the origin of the world to see for the first time as a theater version on March 22, 2020th Franziska Autzen directed the film, and Friederike Schubert took care of the dramaturgy. On September 19, 2020, the Hanover State Theater performed The Origin of the World again as a play. Performances were originally planned until December 2020, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic , the State Theater suspended performance on November 2, 2020. Due to the effects of the pandemic, around ten planned theater productions in front of an audience had to be canceled. Alternatively, the stage adaptation of Der Ursprung der Welt and other current productions of the State Theater Hanover were offered as a video stream . The roughly 90-minute play was also directed by Franziska Autzen. In a form of public abuse, four actresses stand on stage as accusers of patriarchy and present Strömquist's anecdotes, research and thoughts. The stage design is characterized by a heavy, black staircase, over whose steps a red carpet "menstruates" in the front stage area. Imagery from the comic is used very little in the piece.

reception

The origin of the world was generally positively discussed in the German-speaking media, in particular the extensive research, the information content and the quick-witted humor were praised. The simple drawings and uniform panel arrangements have met with some criticism. In Der Tagesspiegel , Marie Schröer states that Liv Strömquist “gives feminist theory a new look and demonstrates the potential of comics for graphic essays”. Strömquist complains about the "taboo, banalization, or demonization of the female sexual organs by church, (pseudo-) scientific or cultural representatives" and her work serves as a "basis [...] for dealing with the consequences of semiotic attributions". At Deutschlandfunk Kultur , Jule Hoffmann highlights Liv Strömquist as a self-confident narrator who “carries out educational work with a lot of passion and at the same time a lot of self-irony”. The work is an instructive “hodgepodge of hair-raising details from sexual research and the cultural history of female sexuality”. Jan-Paul Koopmann writes in Der Spiegel that as omnipresent as bare skin may be, in particular the female, primary sexual organs "are deliberately displaced from the public world of images". Liv Strömquist “shows off her opponents, exposes them as uptight sexists” and does so with “considerable repartee and wit skillfully staged in comics”. Her drawings appear “more like awkward, cartoony talking heads”, but the typeface is “downright exciting”. In the Neue Zürcher Zeitung , Christian Gasser describes the work as "extensively researched, drawn with feminist verve and spiced with caustic sarcasm". It is "[a] informative, entertaining, informative, enlightening and funny". Nadja Schlüter closes when now the praise of the Origin of the World summarize the cultural history of the female sex organ "extremely amusing and informative" together. In the cover culture magazine , Philip Dingeldey comes to the conclusion that although most of the topics are only roughly touched upon, Strömquist is still able, thanks to intensive research, to “reveal facts that are less well known to the public”. It hardly hurts the quality of the book that many pages with uniformly arranged panels are designed rather boring and the drawings often seem rather clumsy. You use the "combination of text and image for a better scenic and pointed representation".

The origin of the world was also received largely positively internationally , with the extensive information content and humor also being emphasized. In The Guardian, Rachel Cooke praises the non-fiction comic about the suppression of female sexuality as witty, astute, but also angry ("[w] itty, clever and angry, this book about the suppression of female sexuality is fantastically acute"). In her article, Cooke particularly emphasizes the last chapter, in which Strömquist criticizes the tampon industry for the “obsession” postulated by the comic artist with terms such as “fresh” and “safe”. For Cooke, the UK edition of Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. The Patriarchy is one of the most important releases of 2018 in the graphic novel category. In Publishers Weekly , the publication is described as a vibrant collection of graphic essays covering a wide range of topics. Strömquist succeeds in striking a balance between serious analysis and disrespectful humor ("embraces an often fraught topic, balancing serious analysis and irreverent, R-rated humor"). Strömquist is less talented than other artists, but her work for Hillary Chute in The New York Times has its own, albeit somewhat weird, charm (“wonky charm”). The comic is instructive, diverse, academic, but also deliberately silly and somewhat strange (" Fruit of Knowledge grew on me because of its weird, hybrid, this-only-really-happens-in-comics tone: It's didactic, goofy, academic "). According to France Culture , Strömquist convinces with a precise and clear analysis. The quick changes between the present and the past, unexpected parallels and the omnipresent humor ("Liv Strömquist nous surprend encore une fois par la justesse et la clarté de son analyze, ses allées et retours effrénés entre passé et présent, ses parallèles inattendus et, surtout, son omniprésent humor au vitriol ”). Despite the bitter tone, Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. The Patriarchy is extremely funny, according to Michael Lorah on Comic Book Resources ("[w] hile the book possesses an underlying bitterness, it's extremely funny"). Already at the third panel he had to laugh out loud while reading. According to Mike Classon Frangos, Strömquist is able to present demanding concepts in an understandable and accessible manner. With the help of the comic medium, she explains complex theories vividly, while at the same time adding an alternative form of representation to the ongoing feminist debate.

Web links

- The origin of the world at avant-verlag

- The origin of the world at Deutscher Comic Guide

- The origin of the world at Perlentaucher

- Kunskapens frukt in the Grand Comics Database (English)

- Reading sample at Der Spiegel

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Nadja Schlüter: The cultural history of the vulva. In: Jetzt.de . April 4, 2017, accessed November 16, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d Marie Schröer: The true size of the clitoris. In: tagesspiegel.de . June 21, 2017, accessed October 10, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mike Classon Frangos: Liv Strömquist's Fruit of Knowledge and the Gender of Comics . In: European Comic Art . tape 13 , no. 1 , March 1, 2020, p. 45–69 , doi : 10.3167 / eca.2020.130104 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e Jan-Paul Koopmann: We have to talk about the vulva. In: spiegel.de . May 9, 2017, accessed October 10, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d Philip J. Dingeldey: Comic - Liv Strömquist: The origin of the world. (PDF) In: titel-kulturmagazin.net . Retrieved November 16, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. the Patriarchy. In: publishersweekly.com . August 1, 2018, accessed February 15, 2021 .

- ^ Hillary Chute: Feminist Graphic Art . In: Feminist Studies . tape 44 , no. 1 , 2018, p. 157 , doi : 10.15767 / feministstudies.44.1.0153 (English).

- ^ Aaron Meskin, Roy T. Cook: The Art of Comics: A Philosophical Approach . Blackwell Publishing, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4443-5484-3 , Why Comics are not Films: Metacomics and Medium-Specific Conventions, pp. 166 , doi : 10.1002 / 9781444354843.ch9 (English).

- ^ Rita Felski: The Limits of Critique . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2015, ISBN 978-0-226-29398-1 , pp. 135 (English).

- ↑ Fredrik Strömberg: Anarkism, punk och feminism . In: Bild & Bubbla . tape 185 , no. 4 , 2010, ISBN 978-91-85161-64-5 , pp. 27 (Swedish).

- ^ Michel Foucault : Discipline and Punish . Vintage Books, New York 1995, pp. 136 (English).

- ↑ Liv Strömquist : The Origin of the World . Avant-Verlag , Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-945034-56-9 , pp. 15 .

- ↑ Chris Bobel: New Blood: Third-Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation . Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick 2010, pp. 160 , JSTOR : j.ctt5hj8bc (English).

- ↑ Sommar i P1 - Liv Strömquist. In: sverigesradio.se . June 24, 2013, accessed May 2, 2021 (Swedish).

- ↑ Krönika: Mensåret 2014. In: svt.se. December 23, 2014, accessed May 2, 2021 (Swedish).

- ↑ Viktoria Jäderling: Upp till menskamp! In: aftonbladet.se . September 13, 2014, accessed April 3, 2021 (Swedish).

- ↑ Kunskapens frukt - Liv Strömquist. In: ordfrontforlag.se. Retrieved February 2, 2021 (Swedish).

- ^ A b Rachel Cooke: Fruit of Knowledge by Liv Strömquist review - eye-poppingly informative. In: theguardian.com . August 21, 2018, accessed February 15, 2021 .

- ↑ Literature and translation - Litteraturprojekt i utlandet, fjärde fördelningen 2018. November 27, 2018, accessed on April 24, 2021 (English).

- ↑ Liv Strömquist: The Origin of the World. In: br.de . March 10, 2017, accessed October 10, 2020 .

- ↑ Nadine Lange: A portrait of Liv Strömquist - Through purple glasses. In: tagesspiegel.de . September 7, 2018, accessed January 6, 2021 .

- ↑ a b c Jan-Paul Koopmann: A gala for the vulva. In: taz.de . October 17, 2020, accessed November 14, 2020 .

- ^ A b Lars von Thörne: Crisis, which crisis? How the comic book industry is holding up in the pandemic. In: tagesspiegel.de . May 25, 2021, accessed October 10, 2020 .

- ↑ Book report topic bestseller ( Memento from February 22, 2021 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ L′origine du monde. In: bedetheque.com. Retrieved April 5, 2021 (French).

- ^ Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. The Patriarchy (Fantagraphics). In: comics.org . Accessed February 24, 2021 .

- ^ Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. The Patriarchy (Virago). In: comics.org . Accessed February 24, 2021 .

- ↑ a b c d Michael C. Lorah: Liv Strömquist Talks Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. The Patriarchy. In: cbr.com. October 15, 2018, accessed February 5, 2021 .

- ↑ Marie Trygg: Mens uppåt väggarna. In: svt.se. October 23, 2014, accessed April 26, 2021 (Swedish).

- ↑ a b Josefine Schummeck: In the Stockholm subway there are posters with menstruating women. In: ze.tt . November 6, 2017, accessed February 24, 2021 .

- ↑ a b c Elle Hunt: 'Repulsive to children and adults': how explicit should public art get? In: theguardian.com . October 8, 2018, accessed March 3, 2021 .

- ↑ a b Elle Hunt: 'Enjoy menstruation, even on the subway': Stockholm art sparks row. In: theguardian.com . November 2, 2017, accessed February 24, 2021 .

- ^ Elise Boutié: Le Divan de Liv. In: timeout.com. May 26, 2016, accessed March 3, 2021 .

- ↑ Liv Strömquist: Le Divan de Liv. In: mutualart.com. 2016, accessed March 3, 2021 .

- ^ Clémentine Gallot: Critique - Liv Strömquist, utérus et coutumes. In: liberation.fr . May 29, 2016, accessed March 4, 2021 (French).

- ↑ Catherine Meyer: Liv Strömquist: le divan de Liv. In: itartbag.com. October 14, 2016, accessed March 3, 2021 (French).

- ↑ Nordwind Festival 2019 - Liv Strömquist: Exhibition. In: kampnagel.de . 2019, accessed March 3, 2021 .

- ↑ Liv Strömquist. In: nordwind-festival.de . 2019, accessed March 3, 2021 .

- ↑ Friederike Schubert: And what's that to do with me? In: haz.de . February 27, 2020, accessed January 6, 2021 .

- ↑ You know so little: "The origin of the world" in Ballhof Eins. In: neuepresse.de . September 20, 2020, accessed January 6, 2021 .

- ↑ Franziska Autzen: The Origin of the World - Based on a comic by Liv Strömquist. In: franziskaautzen.de. Retrieved March 28, 2021 .

- ↑ The origin of the world based on the comic book by Liv Strömquist. In: Staatstheater-hannover.de . 2020, accessed November 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Corona measures - State Opera and Drama are extending the suspension of performance up to and including January 31, 2021. In: Staatstheater-hannover.de . December 2020, accessed January 6, 2021 .

- ↑ Streams of our latest productions. In: Staatstheater-hannover.de . January 2021, accessed January 6, 2021 .

- ↑ Nicolas Garz: outcry against the patriarchy according to Liv Strömquist: The origin of the world. In: die-deutsche-buehne.de. November 29, 2020, accessed January 6, 2021 .

- ↑ a b Christian Gasser: Love - the ideal and the standard. In: nzz.ch . January 5, 2018, accessed April 19, 2021 .

- ↑ The History of the Vulva - A comic about her best piece. In: deutschlandfunkkultur.de . March 15, 2017, accessed October 21, 2020 .

- ^ Rachel Cooke: The Observer - Best books of 2018. In: theguardian.com . December 9, 2018, accessed March 3, 2021 .

- ^ Hillary Chute: When Comics Writers Defy Gender Norms. In: nytimes.com . December 27, 2018, accessed February 15, 2021 .

- ↑ L'origine du monde. In: franceculture.fr . Retrieved February 15, 2021 (French).