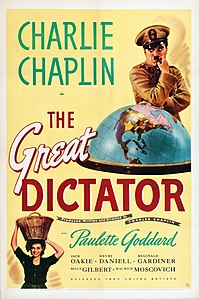

The great dictator

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | The great dictator |

| Original title | The Great Dictator |

| Country of production | United States |

| original language | English |

| Publishing year | 1940 |

| length | 125 minutes |

| Age rating | FSK 6 |

| Rod | |

| Director | Charlie Chaplin |

| script | Charlie Chaplin |

| production | Charlie Chaplin |

| music | Charlie Chaplin, Meredith Willson |

| camera |

Roland Totheroh , Karl Struss |

| cut | Willard Nico |

| occupation | |

|

The rulers

In the ghetto

| |

The Great Dictator (Original title: The Great Dictator ) is an American film by Charlie Chaplin and a satire on Adolf Hitler and National Socialism . The premiere took place on October 15, 1940. The film was particularly successful for Chaplin economically.

action

In the final phase of the First World War , a small Jewish hairdresser on the Toman side fought against both the enemy and the perils of technology. He saves the life of the pilot Schultz, but is so badly injured in a plane crash that he loses his memory and has to stay in hospital for years.

Twenty years later: The dictator Anton Hynkel (orig. Adenoid Hynkel) rules the state of Tomania (orig. Tomainia) and is preparing the invasion of the neighboring country behind the back of the ruler of Bakteria (orig. Bacteria) named Benzino Napoloni (orig. Benzini Napaloni) Osterlitsch (orig. Osterlich) before. His real dream is to rule the world.

With his storm troops, Hynkel is terrorizing the ghetto that is inhabited by Jews and dissidents . The Jewish hairdresser, who has returned from the hospital, and Hannah the laundress, between whom delicate bonds are emerging, are also threatened. But just as the stormtroopers want to lynch the hairdresser because of his resistance , Schultz, meanwhile commander of the stormtroopers, happens to come by and recognizes him as the soldier who saved his life in World War I. Schultz ensures that the ghetto is largely spared from attacks despite Hynkel's tirades of hate against the Jews.

When Hynkel ran out of money for rearmament, he temporarily stopped the oppression of the Jews in order to get a loan from the Jewish banker Epstein. When the latter refuses his credit, the dictator declares the Jews to be his enemies again. Commander Schultz opposes this decision and is therefore sent to a concentration camp by Hynkel . However, Schultz escapes and goes into hiding with his friend in the ghetto. Meanwhile, the dictator enters into an alliance with the country Bakteria, which is also ruled by fascists, and its dictator Napoloni, which is supposed to protect him from intervention by Napoloni in the event of the occupation of Osterlitsch.

The inhabitants of the ghetto plan - instigated by Schultz - an assassination attempt on Hynkel, but are then reminded by Hannah that freedom cannot be achieved through murder and destruction. In addition, no one is willing to sacrifice themselves in a bomb attack on Hynkel's palace. During a raid, Schultz and the hairdresser are discovered and taken to a concentration camp on the border with Osterlitsch. You manage to escape. Both wear uniforms. Because of the resemblance of the Jewish hairdresser to the dictator Hynkel, there is a mix-up. The real Hynkel, who is alone on the duck-hunt nearby in order to conceal the planned invasion of Osterlitsch, is mistaken for the escaped hairdresser and locked up, and the hairdresser is holding the speech that was also broadcast on the radio in front of the people occupied Osterlitsch. The hairdresser uses this opportunity to make a fiery appeal for humanity , justice and world peace , and finally turns to Hannah.

Production background

Background of the film idea

Alexander Korda had suggested to Chaplin to develop a Hitler film with a mix-up between the Tramp and Hitler because they both had the same mustache. Vanderbilt sent Chaplin a series of postcards with Hitler speeches, using his obscene facial expressions as a template. Chaplin also used the speeches and gestures of the newsreel recordings , in which Hitler talked to children, stroked babies, visited hospitals and gave speeches on various occasions.

Film music

Two famous scenes from the film are accompanied by the prelude to the opera Lohengrin by Richard Wagner : Hynkel's dance with the globe and the final address by the Jewish hairdresser. When dancing with the globe, the piece abruptly breaks off before the climax and the balloon bursts. In the final address, however, it reaches its climax and comes to a musically satisfactory conclusion.

The scene immediately after the dance with the globe, which was underscored by the Hungarian Dance No. 5 by Johannes Brahms , gained further notoriety : In this scene, the hairdresser shaves and combs a customer according to the rhythm given by the dance steps of the music. The scene lasts over two minutes and was shot without editing.

Film equipment

The set of the film shows inaccuracies in terms of time. The Hynkel-Hitler resides in something like a baroque castle and sometimes wears, like the Gorbitsch-Goebbels, a white parade uniform studded with medals. Soldier and storm troop helmets look like spiked hoods. This decoration falls more in the time of German emperors and kings. The artistic freedom that Chaplin allowed himself here uses the cliché of the Prussian soldier.

It is likely that Chaplin also looked at pictures of the interior of the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin, which he moved into in 1939 . A published photo shows the "Reichskabinettsaal", in which a huge globe can also be seen. Another globe can be seen on photos in Hitler's 400 square meter study. The "Large Globes for State and Business Leaders" were produced in small series in the 1930s by Columbus Verlag, then based in Berlin-Lichterfelde. Real Hitler very likely did not pursue his power fantasies on a globe, and his interest in the world as an empirical subject was limited. The globes certainly played no part in his war planning. Rather, he attached great importance as a military-strategic autodidact to demonstrate to his extensively trained General Staff officers that he was Germany's real strategist. For these reasons, in every Hitler residence and study there was, in addition to the inevitable globe, the expansive map table that was very often used.

analysis

Satirical equivalents

Although it was his first sound film, Chaplin had the idea of a satirical fictional language , which he implemented for the first time in this still young film technique. So Hynkel's speeches are given in a form of Grammelot in Tomaniac . It is a deliberately incomprehensible language with parts of English and German. The aggressive tone of voice, facial expressions and gestures clearly indicate the content of the message. All in all, the language and rhetoric of Adolf Hitler is satirized.

The artificial word "Schtonk" is used several times and translated with "... is abolished" ("Democracy Schtonk! Liberty Schtonk! Free Sprecken Schtonk!"). Helmut Dietl used it as the title for his satirical film about the Hitler Diary affair in 1992 . The signs and shop labels in the ghetto are sometimes written in slightly distorted Esperanto (e.g. restoraciz for 'restaurant', in Esperanto restoracio , but pronounced in English like rest o 'races ' racial rest'). On a trader's sign, the word “Terpumos” is used as an artificial word for potatoes (Esperanto terpomo = potato).

A running gag is the appearance of individual real German words: "Wiener Schnitzel", "Sauerkraut", "Blitzkrieg", "straff", "Leberwurst", "Stolz", "Katzenjammer".

As part of his satire on Nazi rule, Chaplin also parodied the names of states and politicians. The racial concept of the Nazi ideology remained unpersiflated in the film, however , because terms such as “ Jew ”, “ Aryan ”, “ Ghetto ” and “ concentration camp ” were not alienated.

The equivalents of the satirically alienated proper names are as follows:

- Tomania (English Tomania) = "Germania" / Germany ; Allusion to Ptomain = corpse poison, but also to to mania 'in the madness' (whereby Chaplin caricatured Germany's megalomania)

- Bacteria = Italy

- Osterlitsch (Engl. Osterlich) = " Austria " / Österreich , one could also recognize an allusion to Austerlitz .

- Anton Hynkel (English Adenoid Hynkel) = Adolf Hitler ; Adenoid could be derived from the medical meaning of “ adenoids ” or from the contraction of the name “Adolf” and the word “ paranoid ”, but it can also be associated with “ Android ”. Ironically, a Hans Hinkel , initially special advisor for Jewish issues and responsible for the ousting of Jewish Germans from the cultural scene, was later actually supposed to lead the Nazis' film propaganda.

- Benzino Napoloni = Benito Mussolini ; Allusion to gasoline and Italian Napoleon

- Field Marshal Herring = Hermann Göring

- Dr. Gorbitsch (English Dr. Garbitsch) = Dr. Joseph Goebbels , US-Engl. garbage 'garbage'

- Aroma (Italian Roma) = Rome

- Bretzelberg = Salzburg

Chaplin showed a flair for comedy and satire by using the stylistic devices belittling, exaggeration and inversion in film. The charged Italian dictator is given the explosive word gasoline by name, the German the less heroic word Hinkel for domestic chicken, the well-known fat Göring the word herring, in the opposite sense of "thin as a herring" .

The symbol of Hynkel's dictatorship is a double cross, an allusion to the swastika as a symbol of the National Socialists. In the English language, the term double-cross is a synonym for ' double play '.

Language of images

Chaplin uses the visual form of expression masterfully. In fascist propaganda, the difference in size between the relatively small dictator Mussolini and his only slightly larger German counterpart Hitler was often masked by tricks in the recording technology. In the film these facts are satirically reversed and downright celebrated. This is also how the allusion in the film title is to be understood, “great” for big or great. At the latest when Napoloni and Hynkel compete when they visit the hairdresser together for the greatest possible extendibility of the respective hairdressing chair, this is taken to extremes.

The swastika, faked into two simple crosses, is overwhelmingly omnipresent in the film and thus exposes the omnipotence of the apparatus of subjugation. It seems like the signature of an illiterate man with three crosses , stamped on all system parts. This is particularly noticeable in connection with the satirical artificial language used by Hynkel, which is only indirectly understandable. Napoloni, on the other hand, has two sides of the cube (a one and a six) as an armband symbol, which also reflects any interchangeability of such symbols of power.

The film follows various basic patterns, such as the depiction of the dictators and weapons and war as a threat. For example, Hynkel is presented with a Hynkel salute, raised behind a large clock that shows “shortly before twelve”, and at his party congress dark clouds hang over the crowd that has gathered to the horizon. If the Jewish hairdresser dances for his life with the grenade of an intimidatingly large cannon at the beginning of the film, later the world is figuratively the plaything of the power-loving Hynkel when he dances with his globe and it finally bursts like a soap bubble.

The "Hynkel salute" shown, based on the Hitler salute, is presented in obvious exaggeration with every greeting, agreement or farewell. In one shot, famous works of art, the Venus de Milo and the thinker Rodin , are presented with the left arm raised in a reversed “Hynkel salute” - the reversed side parodies the Hitler salute as a stylistic device often used in film.

The process of publicly staged state receptions, as it were in the Nazi era, known since the imperial era with the winged term “Great Station”, is denigrated as a laughing stock in the film. Napoloni and his wife are jerkily shuffled back and forth in the car and the red carpet is wildly crazy until the state guests can finally alight in accordance with the protocol .

Adolf Hitler with the architect and the globe to the side

The two main characters

Adenoid Hynkel

Hynkel is a parody of Adolf Hitler and is played like Chaplin's hairdresser. Chaplin makes use of physical similarities with Hitler. The Hynkelhitler is certainly given some talents in the film, in rhetoric, self-staging, influencing the masses, playing the piano and even ballet-like dancing. However, he is extremely arrogant and instead of files has mirrors in his office cupboard in which he demagogically rehearsed the facial expressions for his extremely important speeches. He is diligent, persistent and focused in realizing his goals, but constantly allows himself to be distracted by unnecessary duties. He often shows immaturity and unprofessionalism. Once he climbs up a long curtain in his office because he wants to be quiet from Gorbitsch. This is an example of childish behavior. He is also unable to make political decisions on his own, and can easily be influenced, especially by Dr. Gorbitsch. Hynkel is easy to get upset. Often he is uncontrolled, hasty in reactions and acts rashly. He is brutal and ready to kill 3,000 workers just because they are about to strike. Hynkel's ideas of a future world show parallels with Hitler. This irrationally wants to exterminate all Jews. But the brown-haired Hynkel wants to destroy brunette too. Only lack of money forces him to briefly hide his hatred. In his mania for power he went over corpses without hesitation, for example in the course of his plans to conquer Osterlitsch, in which the losses of his own soldiers did not affect him in the least.

His behavior towards the female sex is that of a predator for prey, he suddenly attacks his secretary and simply knocks her over, but gives priority to immediately reported government business. Overall, Hynkel can be characterized as arrogant, vain, intolerant, obsessed with power, bossy, excessive, lacking empathy, immature, unprofessional, dependent on political decisions, uncontrolled, hasty, rash, impetuous and irrational. But the figure of Hynkel is no longer that of the slapstick villain who just hits everything. Rather, Dictator Hynkel is a detailed psychogram of a small-minded megalomaniac who threatens the entire world.

The hairdresser

At the beginning of the film, the Jewish hairdresser is quite unhero-like and rather involuntarily a Tomaniac soldier in the First World War. This can also be seen in the fearful and clumsy handling of weapons. He is obviously not familiar with handling grenades and other war tools. Despite enormous fear and ignorance, he stands up for his comrades. In the fog of battle , the difference between one's own comrades and the enemy is so blurred that the hairdresser, oddly enough, even briefly joins an enemy patrol. His art of war lies in a quick assessment of danger, but above all in running away. He is forced to obey orders, but does not obey unconditionally. The hairdresser has obviously never flown an airplane himself, but with courage and self-confidence he not only saves himself, but also Commander Schultz on their escape. The character of the hairdresser is characterized by the fact that he - often spontaneously and without thinking of possible consequences - stands up for his fellow men. He loves his hairdressing profession dearly and his small salon is one of the most important things in his life. After his military service, he is not aware of how much the political situation has changed to his disadvantage, and so he defends himself with enormous ambition against attacks by whole hordes of Hynkel's stormtroopers.

In addition to his hairdressing business, Hannah the laundress plays a major role in his life. The desire arises in him to spend his future with her, and he dreams of escaping into exile together. In addition to his cordiality, the hairdresser is characterized by the fact that he is a very modest, courteous, friendly and helpful person. He is very polite and apologizes in any situation where he thinks he has done something wrong. The figure of the little hairdresser is built up in the film as a popular figure from the start and has many of the characteristics of the figure of the tramp from Chaplin's earlier films. At the end of the film, when the hairdresser, who had been mistaken for Hynkel, involuntarily gets to the lectern and in front of the crowds in Osterlitsch, he - as before - is afraid of being exposed and of risking his life. But at this moment, the future of his country and humanity is more important to him than his own existence. He stands by his principles, acts according to his feelings and fights Hynkel's politics. To him, humanity means more than power. The possibility of taking over the dictator's position of power and his way of life is far from him. Instead of wealth and power, the hairdresser's focus is on saving the oppressed minority. Despite the dangerousness of Hynkel and his state apparatus, he used the opportunity during the address to open the eyes of the people and to promote humanity and peace.

Chaplin did not use a specific name for the figure of the hairdresser, this is an indication that this stands for people in general and therefore also for the viewer himself, who is called by the film to defend himself. The hairdressing roll has many slapstick-like stylistic devices from Chaplin's silent film tramp. With his film, Chaplin shows that everyone can do something against inhumane politics and that one cannot simply join a majority. It is therefore possible as an individual to point out what is injustice and thus to move crowds, just as the hairdresser does in the speech at the end of the film. Individuals - as he portrays it - can certainly improve the world.

reception

| source | rating |

|---|---|

| Rotten tomatoes | |

| critic |

|

| audience |

|

| IMDb |

|

American domestic reviews

Chaplin's work contributed to the internal American debate about the entry of the United States into the war . The New York Times rated it as "perhaps the most important film that has ever been made," while the newspapers of Press Tsar William Randolph Hearst accused Chaplin of inciting war. In Chicago , due to the high proportion of people of German origin, no cinema dared to show the film, but in the long term it became Chaplin's most financially successful project.

A scene in the film that is mostly rated negatively is the one in which concentration camp prisoners march, which in the opinion of most critics is depicted excessively ridiculous. Chaplin later apologized for this scene, not knowing how horrible it really was in the concentration camp. "If I had known about the horrors in the German concentration camps, I would not have brought about The Great Dictator , I would not have been able to make fun of the murderous madness of the Nazis," wrote Chaplin years later in his autobiography.

"Truly outstanding work by a truly great artist and - from a certain angle - perhaps the most significant film that has ever been made."

Influence of the film

Chaplin's contribution enabled other directors to portray the character of Hitler in a ridiculous manner. In 1942 Ernst Lubitsch also made a comedy about the personality cult and the real exercise of power with to be or not to be (based on the text Poland is not lost by Melchior Lengyel ), which, however, only had a small audience. See also Kortner's scenes about the Vienna Hotel Imperial with a Hitler doppelganger.

In the Third Reich

According to Budd Schulberg , who sifted through evidence for the Nuremberg trials , among other things , Hitler had requested the film twice within a short period of time. It has not yet been proven whether he actually saw the film. It was not performed in public. In the sphere of influence of the German Empire, however, there were different copies in different languages. Josip Broz Tito's partisans succeeded in exchanging a German propaganda film in a Wehrmacht cinema for one of these copies; officers present ended the performance about halfway through and threatened to shoot the Yugoslav employee who operated the projector.

In post-war Germany

The writer Alfred Andersch was indignant when he was called in November 1946 that a delegation of filmmakers, after viewing them in a Berlin cinema, considered the time for a public screening to be far too early. A student reader, who had attended the performance as a guest, countered that the film shot with an outside view did not reflect the actual cruelty and therefore hurt those affected. One of their evidence was the concentration camp scene mentioned above.

One of the two main agencies of the Information Control Division (ICD) - an American propaganda and censorship department in Germany - the Information Control Section (ICS) in the American sector of Berlin, made a very short-term program change in the Berlin-Steglitz public cinema for test purposes one. On August 19, 1946, the US magazine Time reported that the Germans - who actually came to the announced film Miss Kitty - laughed when Chaplin in the role of the Jewish hairdresser shaves a customer to Brahms music and Hynkel as the dictator Dances around balloon globe until it explodes in his face. But over time the laughter stopped and an embarrassing, then concerned silence spread and nobody laughed anymore during the concentration camp scenes. All in all, the film would have been a nightmare for the audience and the time of the Nazi tragedy - as they had cheered their "Great Dictator" - still too close.

The New York Times, August 10, 1946, noted that the main impression was that people were in control of their emotions. There was only “spontaneous laughter” about the Göring parody - the most vain of the Nazi leadership. On the other hand, they reacted “irritated and hurt” when Chaplin parodied the dictator in artistic language and imitated Hitler's threatening speech with original sounds and scraps of German words.

A total of two performances took place. ICD questionnaires were handed out. Of the 500 sheets distributed, only 144 were handed in after the first performance and 232 after the other. The film achieved a high approval rate. It was rated “excellent” or “good” by 75 percent on the first evening and by 84 percent on the second. When asked whether the film should come to German cinemas, 69 percent initially answered in the affirmative and then 62 percent. However, the low participation speaks against a high level of approval for the film.

The literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki commented on the ZDF television program Das Literarisches Quartett that no one had ever succeeded in drawing the ultimate portrait of the dictator Hitler, who was most permanently burned into the collective memory of our society, whereupon his critic Hellmuth Karasek protested that it was Chaplin who succeeded in doing this with the film The Great Dictator .

“Chaplin's portrayal of Hitler is terrific. The moments in which he onomatopoeically imitates the Fiihrer's speeches are particularly brilliant. For a long time he successfully studied the gestures and facial expressions of Hitler in newsreels. Precisely because he uses an artificial language and thus eludes the actual meaning of the speech, the viewer can concentrate all the more on its 'presentation'. The parody becomes all the more apt. If Hitler were an unknown species that uttered such sounds and gestures, one would immediately consider them malicious. Every now and then, individual bits of word are to be understood, such as 'Wiener Schnitzel'. For German viewers in particular, this offers an additional comical aspect. In any case, 'The Great Dictator' vacillates between comedy, parody and sharp criticism of Hitler. In retrospect, some accused Chaplin of the comedic part and the seemingly associated trivialization of National Socialism. At the time of production, however, the real disastrous extent of the Hitler regime could not be foreseen. Chaplin was therefore more prophetic than negligent in dealing with the subject. "

“The lonely pas de deux with the globe to Wagner music (Lohengrin, prelude and first act), Mussolini's arrival at the train station (Chaplin occupied with a congenial rival, Jack Oakie), the ascent to the bets on the hairdressing chairs - these are all scenes who wrote film history and contemporary history. You can see over the idyllic, kitschy ghetto scenes. What matters is not that Chaplin couldn't have known better, that is, more terrible. The bottom line is that slapstick cannot work if the opponent, no matter what, reacts brutally and bluntly with pistol and obliteration. Chaplin, the great master of the silent film (his 1936 black and white silent film 'Modern Times' is still one of the key films of the modern and postmodern), made the 'Great Dictator' as a sound film, and it is fair to admit that sweet dialogues in the ghetto come painfully close to the licorice rasps of the silent soap operas. [...] The closing speech that the fake Hitler (the Jewish hairdresser) is giving in Vienna is not so happy - a speech that trembles with humanity, freedom, and belief in peace - one of the most beautiful speeches of all time , dripping with good intentions. "

“Chaplin's first dialogue film is a personal and political commitment. The story goes back to 1935 and shows how difficult it was for the director to find a suitable form for his message. It ended up being a film devoid of artistic homogeneity: a sad farce, a clairvoyant slapstick satire. The appeal at the end is out of the ordinary due to its simple directness. 'The Great Dictator' has ingenious, very funny and deeply moving traits, but the strenuous effort behind it remains disturbing in the viewer's consciousness. As a time and character testimony of lasting interest. "

In Rome

When the Americans showed the film to viewers in the newly liberated Rome in October 1944, there was a desire to postpone such a cinema program. The New York Times reported at the time that after the screening "the audience went out of the cinema numb". The newspaper speculated: “People admired him for a long time and today they don't like to be told that they chased a buffoon.” But the first performance in Italy was already two years later.

Awards

The Great Dictator was nominated for five Oscars in the categories of "Best Picture", "Best Original Screenplay" (Chaplin), "Best Actor" (Chaplin), "Best Original Music" ( Meredith Willson ) and "Best Supporting Actor" (Jack Oakie), then went completely empty-handed at the award ceremony.

In 1997 the film was entered into the National Film Registry .

other

- Hitler and Chaplin had their birthday in the same month and year, in April 1889. It is also interesting that Hitler wore his mustache similar to Chaplin's film character The Tramp. But that can be explained with the fashion of the time. Such a mustache was just modern in those times.

- The silent film comedian Hank Mann makes a brief appearance in the film as a stormtrooper who steals a fruit.

- The German band Varg used the closing speech from the film for the intro of their 2016 album Das Ende aller Lügen . The content of the speech (intro) is in complete contrast to the dark and martial other songs on the album.

- In the film, the " Big Bertha " is described as a gun that is able to hit Paris from a distance of 160 km. A gun of that name actually existed, but had a significantly shorter range. Rather, the “ Paris gun ” with a range of 130 km served as a model. This hit the church of St-Gervais-St-Protais (in the film Notre Dame ).

- The band Coldplay used the closing speech from the film for the intro of the music video for the song A Head Full of Dreams .

- The American hardcore band Stick to Your Guns used excerpts from the closing speech for their piece of music I Choose Nothing on the 2015 album Disobedient .

synchronization

The synchronization was created in 1958 under the dialogue book and the dialogue direction by Franz-Otto Krüger from Ultra-Film .

| role | actor | Dubbing voice |

|---|---|---|

| Hairdresser / dictator Anton Hynkel | Charles Chaplin | Hans Hessling |

| Hannah | Paulette Goddard | Hannelore Schroth |

| Benzino Napoloni | Jack Oakie | Werner Peters / Alexander Welbat |

| Commander Schultz | Reginald Gardiner | Siegfried Schürenberg |

| Field Marshal Hering | Billy Gilbert | Werner Lieven |

| Dr. Gorbitsch | Henry Daniell | Friedrich Schoenfelder |

| Artillery Officer ( Big Bertha ) | Leyland Hodgson | Arnold Marquis |

| Levy | Max Davidson | Alfred Balthoff |

| Radio announcer | Wheeler Dryden | Heinz Petruo |

| reporter | Don Brodie | Horst Gentzen |

| Heinrich Schtick | Wheeler Dryden | Paul Klinger |

| police officer | Benno Hoffmann |

In 1972 the film was brought back to the cinema by Tobis Distribution - but one role in the German version had been lost. Instead of re-dubbing it (as would have been the norm at the time), they wanted to keep the classic German dubbing and only dub the missing scenes, although Werner Peters had died in the meantime and a different narrator had to be used with Alexander Welbat. This means that this film should be the first whose original synchronization was obtained by resynchronizing missing scenes.

World premieres

The only information about the film that Chaplin himself gave to the press at the beginning of 1940 caused a sensation and read: "The premiere is to take place in Berlin". The film was then premiered as follows :

- USA : Premiere in New York on October 15, 1940, general release on March 7, 1941

- Great Britain : December 16, 1940

- Serbia under German military administration : May 1942 (in a Wehrmacht soldiers' cinema )

- France : April 4, 1945

- Italy : October 9, 1946

- West Germany : August 26, 1958

- Japan : October 15, 1960

- Spain : March 22, 1976 (after the death of Francisco Franco )

- GDR : March 4, 1980 on DFF 1

In 1946 the film was shown to a small group of politicians and the press in Berlin. After a vigorous exchange about the maturity or immaturity of the German population, a majority of those gathered spoke out in favor of a public screening. The Americans did not approve the film, however, and it would be twelve years before it came to West German cinemas.

Restored versions

On December 30, 2004, The Great Dictator was shown again in a restored version. The Italian Cineteca di Bologna and the copy company Immagine Ritrovate were responsible for the new version . A film copy made from a complete original negative was used to restore the image. In this way, the original contrasts and the lighting mood could be restored. To renew the sound, an original tape with the final mix was used and scratches and other errors in the sound track were removed using digital technology. In May 2010 another completely restored version of the film was released on Blu-ray Disc , based on a new digital scan of film rolls from the Chaplin family's private home theater. The audio track is available on this Blu-ray Disc in the DTS HD Master Audio 2.0 Mono format.

Film about the making of

- Kevin Brownlow , Michael Kloft (Direction): The Tramp and the Dictator. Great Britain 2002, 65 min. (Was broadcast in 2008 together with the documentary film Hollywood and Hitler by the same authors under the title Hitler and the Dream Factory: How Hollywood Laughed at the Dictator ... ) The documentary showed, among other things, previously unknown scenes in color. However, it was not film material from the studio, but private recordings of Chaplin's older half-brother Sydney Chaplin .

See also

literature

- Charlie Chaplin: The roots of my comedy . In: Jüdische Allgemeine Wochenzeitung , March 3, 1967, abridged: again ibid. April 12, 2006, p. 54

- S. Frind: The language as a propaganda instrument of the national socialism . In: Mutterssprache , 76, 1966, pp. 129-135

- Ronald M. Hahn, Volker Jansen: The 100 best cult films - from Metropolis to Fargo . Heyne, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-453-86073-X .

- Jörn Glasenapp : The great dictator . In: Heinz-B. Heller , Matthias Steinle (Hrsg.): Film genres: Comedy . Reclam, Stuttgart 2005, pp. 187–192, ISBN 3-15-018407-X / ISBN 978-3-15-960133-5 (2012 as e-book).

- Nikos Kahovec: Chaplin vs. Hitler. A historical investigation of “The Great Dictator” taking cinematic-aesthetic aspects into account . Master's thesis at the University of Graz 2007, textfeld.ac.at (PDF; 3.1 MB; 173 pages)

- Norbert Aping: Liberty shtunk! Freedom is abolished. Charlie Chaplin and the National Socialists . Schüren, Marburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-89472-721-5 .

Web links

- The Great Dictator in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- The Great Dictator atRotten Tomatoes(English)

- Ulrich Behrens: Film review of The Great Dictator . In: Filmzentrale.com

- Benjamin Happel: Film review for The Great Dictator . In: Filmzentrale.com

- The complete closing speech ( memento of October 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) on Zelluloid.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Annette Langer : “Excellent accounting with Hitler” . In: Spiegel Online TV , 2002.

- ↑ Wolfgang Tichy: Chaplin . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1974, p. 99

- ↑ Wolfgang Tichy: Chaplin . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1974, p. 100

- ↑ Ulf von Rauchhaupt: Cartography: The whole world in human hands .

- ^ Sven Felix Kellerhoff: Auction: Adolf Hitler's globe was much larger . November 14, 2007.

- ↑ Bettina Gartner: Sign here. In: The time . January 4, 2005, accessed May 26, 2020 .

- ↑ a b great d at Rotten Tomatoes , accessed April 2, 2015

- ↑ The Great Dictator in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ arte.tv/de ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Alfred Andersch: Chaplin and freedom of the mind . In: The reputation. Independent papers of the young generation . No. 7 . Munich November 15, 1946, p. 8 .

- ↑ Jutta Bothe: Should one show Chaplin's “Dictator”? In: The reputation. Independent papers of the young generation . No. 13 . Munich February 15, 1947, p. 15 .

- ^ A b Süddeutsche Zeitung , Niels Kadritzke: Charlie Chaplin's Hitler parody. Fiihrer orders we laugh! May 19, 2010

- ↑ arte.tv/de, December 20, 2004 ( Memento of February 6, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Triumph of Comedy . tagesspiegel.de, February 16, 2002

- ↑ The great dictator. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed March 2, 2017 .

- ↑ Varg - The End of All Lies CD Review. (No longer available online.) In: The Huffington Post . January 2, 2016, archived from the original on February 21, 2019 ; accessed on July 21, 2016 .

- ↑ Coldplay: Coldplay - A Head Full Of Dreams (Official Video). August 19, 2016, accessed March 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Sumerian Records: STICK TO YOUR GUNS - I Choose Nothing (Feat. Scott Vogel). February 7, 2015, accessed June 10, 2019 .

- ^ Entry in the synchronous database ( Memento from February 6, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) by Arne Kaul

- ↑ Release dates for The great dictator

- ↑ Making of: Great .

- ↑ Sortie en France du film de Charlie Chaplin Le Dictateur ( Memento from November 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Il grande dittatore ( Memento from April 13, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Hanns-Georg Rodek: How Chaplin recaptured Hitler's beard .

- ↑ Klaus Tollmann, www.stage01.de: Charlie Chaplin - The Great Dictator .

- ↑ The Great Dictator Blu-ray .

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg, Germany: Print version - Chaplin's settlement with Hitler: The tramp and the dictator - SPIEGEL ONLINE - SPIEGEL TV .

- ↑ Heil Hynkel! In: Der Spiegel . No. 7 , 2002 ( online ).