Desaparecidos

Desaparecidos (Spanish; the disappeared , Spanish pronunciation [ des.a.pa.ɾe.ˈθi.ð̞os ], in Latin America [ des.a.pa.ɾe.ˈsi.ð̞os ]) is a common name in many countries in Central and South America for people who have been secretly arrested or kidnapped by state or quasi-state security forces and then tortured and murdered. Based on this original meaning, the term has recently been used increasingly in Spain for victims of the Franco dictatorship .

The term is explained by the practice of military dictatorships that was common from the 1960s to the 1990s , especially in Argentina , Brazil , Chile , Paraguay , Peru , Guatemala , El Salvador and Uruguay ; political opponents or even people who are unpopular are disappearing let . The victims are arrested or kidnapped and taken to a secret location . The relatives and the public learn nothing about the sudden "disappearance" or the whereabouts of the person who has disappeared. The victims are usually killed after a short to several months imprisonment, in which they are usually severely tortured, without a judicial process and the bodies disposed of. Since the murder is usually kept top secret and state authorities strictly deny any involvement, the relatives often remain in a desperate state for years between hope and resignation, although the victim was often killed a few days or weeks after his disappearance.

According to estimates by human rights organizations, the Latin American military dictatorships in the 1970s and 1980s caused a total of around 35,000 people to permanently “disappear” in this way as part of so-called “dirty wars ”. In many of the countries, the criminal law processing of these crimes did not begin until around the 2000s and continues to this day.

Historical and political classification

The disappearance of political opponents was and is still practiced in many countries around the world, mostly ruled by authoritarian or dictatorial lines . The cases in the South American countries are characterized above all by the fact that the phenomenon occurred in a relatively short period of time in the majority of the countries of South America and the states concerned were ruled by right-wing military dictatorships of a similar type . In addition, at least six of these countries worked together - with proven, but to date not fully understood, US support - as part of the multinational intelligence operation Operation Condor , in which they helped each other in the persecution and illegal killing of political opponents . Forced "disappearance" of people has been defined as a crime against humanity in international law since 2002 .

In the 1980s and 1990s, the era of Latin American military dictatorships, almost all of which were supported by the United States, came to an end. The injustice previously committed against the Desaparecidos was for a long time only inefficient or not at all legally prosecuted under the pressure of the still powerful military in the young democracies, which led to considerable disappointment and bitterness among the bereaved. It was only from the 2000s that an effective legal appraisal began in several countries, a large number of legal proceedings were opened and many perpetrators of the time have now been sentenced to long prison terms - including a number of torturers from the lower echelons of the military, but also several who were in command at the time Junta Generals. The process of processing has not been completed, and many criminal proceedings are still ongoing today. Some older perpetrators, mostly from the higher ranks at the time, were able to avoid punishment due to old age or death, such as the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet .

backgrounds

In the second half of the 20th century many of the supported Latin American military dictatorships their violent repression practice in a new, under strict secrecy carried out and as a disappearance or Forced disappearance designated (desaparición forzada) technique of repression . It largely replaced the previously practically official torture and murder of regime opponents. The basis was the doctrine of national security, also propagated by US military strategists, which defined the enemy to be destroyed as in the midst of society ( enemigo interno ). Thus, the circle of supposed enemies of the state of armed groups organized in guerrilla associations or communist movements was expanded to include large parts of the population. This redefinition of the concept of the public enemy to any subversive person who was not acceptable to the respective regime resulted in a repressive penetration of the entire society, in which almost everyone could become a victim. A quote from the Governor of the Province of Buenos Aires , General Ibérico Saint Jean, from 1977 is particularly indicative of the consequences of this strategy :

"Primero mataremos a todos los subversivos, luego mataremos a sus colaboradores, después [...] a sus sympatizantes, enseguida [...] a aquellos que permanezcan indiferentes y finalmente mataremos a los tímidos"

"First we will kill all subversives, then their collaborators, then their sympathizers, then the undecided and finally the timid"

In Argentina, the rulers described their approach as a dirty war (guerra sucia) against the so-called subversion . Enforced disappearance tactics began in Latin America in the mid-1950s, after the CIA- organized coup against President Guzman in Guatemala . It was practiced there almost continuously until around the turn of the millennium.

In a text by the Heinrich Böll Foundation , the topic was described as follows:

“Ideologically armed with the doctrine of national security , which was also inspired by the USA , the Latin American military justified their claim to a central role in the state and society since the 1960s. They saw themselves as the only force capable of leading the nation state. The military dictatorships took control of national development and internal security . This was legitimized with the construct of an "internal enemy" who was physically destroyed to defend the "national interests" and large parts of the population had to be controlled to combat it. "

For more background, see: Relations between Latin America and the United States # 1970s: The Era of the Juntas

Arrest, Torture and Murder

In practice, enforced disappearance meant that people were arrested from everyday situations or at night by members of the security forces ( military , secret police , secret services ) who remained anonymous without giving reasons - attention was usually paid to the quick, inconspicuous execution and secrecy of the arrest, so that the reasons for the "disappearance" of humans remained unknown to their relatives. Since they did not know whether and which state organs were holding their family members prisoner, or whether they had actually "disappeared" for other reasons, the seekers often began a desperate odyssey through police stations, hospitals and prisons. It should be noted - to understand the situation of the relatives - that the Argentine dictatorship consistently denied until the end of its rule that it had anything to do with the disappearance of these people. Since the courts were also the henchmen of the respective dictatorships, the relatives were completely powerless against this practice and, after years of searching, were often only able to give up if the victim's body was not found at some point or, in rare cases, it was finally released. In Argentina, it often happened that the parents of young men in authorities were told with a wink that it was well known that young men would often move abroad if they "accidentally" made a woman pregnant.

Typically, abductees were detained and tortured for several days at military bases or civilian locations, such as disused auto repair shops, until they were killed. This provided any number of informants whose interrogation under torture generated new names of suspects. The state could dispose of the life or death of the supposed enemy without having to devote itself to lengthy legal processes or nationally and internationally politically responsible. The bodies of the disappeared were either buried in anonymous, secret mass graves (e.g. in Chile), in the sea (Argentina), in volcanoes (Nicaragua) or in rivers or left along streets, in university buildings, chimneys and other public places. In Argentina, the Naval Technical School ( Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada ) in Buenos Aires was one of the main centers of repression. It is estimated that around 5,000 people were tortured there and then - with the exception of around 200 survivors - murdered.

The Argentine writer Rodolfo Walsh wrote as early as 1977 on the first anniversary of the Argentine dictatorship from the underground in his open letter from a writer to the military junta :

“15,000 disappeared, 10,000 prisoners, 4,000 dead, tens of thousands who have been driven out of the country - these are the bare numbers of this terror. When the traditional prisons were overcrowded, they turned the country's largest military facilities into regular concentration camps , to which no judge, no lawyer, no journalist, no international observer had access. The use of military secrecy, declared inevitable for the investigation of all the cases, makes the majority of arrests de facto kidnappings , which enables torture without any restrictions and executions without a court judgment. "

On May 17, 1978 the daily newspaper La Prensa (Buenos Aires) published the result of the research of the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights (Asamblea Permanente por los Derechos Humanos) founded in 1975 : a list of 2515 names of "disappeared". In 1318 of these "disappeared" the authorities had officially informed the relatives who had asked about the whereabouts of the arrested persons that they knew nothing about their whereabouts. The authorities did not respond to the remaining 1,197 men and women, but the documentation of these cases by the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights indicated that they had been “picked up”.

According to testimony from former military personnel, many Argentine disappearances were thrown alive and naked from military aircraft over the open sea after being previously drugged. A plane with ten to fifteen prisoners on board took off regularly every Wednesday. About 2000 people are said to have died in these " death flights " (Vuelos de la muerte) in two years. The Argentine public was particularly shocked by reports that the perpetrators were regularly cared for by military pastors. They played down the acts as a “humane and Christian way of death”. The events came to light in 1996 through a book by the well-known Argentine journalist Horacio Verbitsky , which was based on interviews with former Marine Adolfo Scilingo . Scilingo was sentenced to long imprisonment by a Spanish court in 2005, based in part on his testimony to Verbitsky. During the trial, he denied the actions and claimed to be innocent.

For a detailed description of the Chilean situation see Torture in Chile .

Psychological destruction

The wall of silence that formed around the abductees was particularly stressful for the relatives and friends of the victims: In hospitals, prisons and morgues, the relatives searching were told that nothing was known about the fate of the disappeared. In not a few cases it was said that the wanted man probably ran off with another woman or had abandoned his family in order to leave for the United States. Days, weeks, months, and finally years of uncertainty passed, during which the relatives remained in an uncanny state of limbo. Former friends and acquaintances no longer greeted them on the street for fear of being put in touch with the affected family. Second-degree family members denied their relationship to the disappeared; in some cases even the immediate relatives tried to hide the fate of their disappeared so as not to become socially isolated. In the course of time it became increasingly unlikely that the disappeared would reappear alive, and yet it was psychologically impossible to grieve the loss of loved ones: If the disappeared's death were accepted and a process of mourning, consolation and finally resolution was initiated, the survivors would, as it were, be guilty of betrayal of what might still be living. In addition, a new beginning was impossible for many partners of the disappeared because they were not officially widowed.

A disappeared person is not a simple political prisoner, nor is a dead person, although there have been cases of dead bodies found for which no one has been held responsible. Enforced disappearance is different from clandestine murder in that when the victim's body disappears, the evidence disappears. To be gone doesn't mean to be dead. Members of relatives' organizations therefore demand the exhumation of secret mass graves in the hope of finding the bones and bones of their loved ones and burying them appropriately.

Coordinated approach

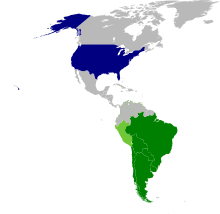

Green: participating states,

light green: partially participating states,

blue: supporting states. To date, the role of the USA is not nearly completely cleared up.

This procedure against all kinds of "opponents of the regime" was organized as part of the so-called Operation Condor by the secret services of six South American countries. The American secret service CIA (see also School of the Americas ) and French military advisers played a role as advisers and supporters that was not nearly completely cleared up, but which, according to a large number of published government documents, was considered to be secure .

The influence of the "French doctrine"

The French journalist Marie-Monique Robin has published extensively about the fact that the techniques underlying state oppression were based in part on the so-called French doctrine, which had been developed by the French military for the Algerian war in the 1950s . They were accordingly exported to Latin America from 1959, where they were first used on a large scale in the 1970s in the military dictatorships in Chile and Argentina. French military and intelligence advisers also played a central role in training some of the intelligence services involved in Operation Condor in various methods of repression.

The role of Henry Kissinger

In particular, the US security advisor (1969–1973) and foreign minister (1973–1977) Henry Kissinger is accused on the basis of documents of having actively supported Operation Condor and similar activities, as he feared communist revolutions in Latin American countries ( Domino- Theory ) and saw the dictatorial rulers as allies of the USA in the fight against communism. Under Kissinger as security advisor, the USA played a role that has not yet been fully clarified in the 1973 coup in Chile , which was at least heavily promoted by the CIA .

The Argentine military junta believed that it had the approval of the US to use massive force against political opponents in the name of a national security doctrine in order to fight their "terrorism". This was based, among other things, on a meeting between the Argentine Foreign Minister Admiral Guzzetti and Kissinger in June 1976, who, contrary to expectations, had given positive signals to a tough approach to solving the "terrorism problem". Obviously, this was seen as a license to terrorize the opposition. Robert Hill, the US ambassador to Argentina, complained in Washington about the “euphoric reaction” of the Argentine after the meeting with Kissinger. Guzzetti then reported to the other members of the government that, in his opinion, the United States was not concerned with human rights , but that the whole matter would be "resolved quickly". The military junta subsequently rejected petitions from the US embassy regarding the observance of human rights and referred to Kissinger's “understanding” of the situation. Hill wrote after another meeting of the two:

"[Argentine Foreign Minister] Guzzetti reached out to the US in full expectation to hear strong, clear and direct warnings about his administration's human rights practice; instead he came home in a state of jubilation, convinced of the fact that there was no real problem with the US government in this matter. "

Child robbery and forced adoptions

In Argentina, it was common practice to give children born in custody of abducted and later killed women to officer's families without children. After the end of the dictatorship in 1983, many grandparents and remaining parents tried to find these children again. The organization Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo estimates that there are a total of around 500 children in Argentina who were kidnapped by the henchmen of the dictatorship and then secretly given up for adoption. In at least 128 cases, children who had disappeared during the military dictatorship were returned to parents or rightful families by 2018. The efforts continue. The confrontation with their true origins is usually a very painful process for the now grown-up children - also because their supposed fathers were often involved in the torture and murder of their actual birth parents. Some of these now grown-up children have founded the organization Hijos , which advocates harsh criminal prosecution of the perpetrators of the time, regardless of their mostly very advanced age today.

resistance

In 1977, the mothers of the disappeared founded one of the few open opposition groups against the military dictatorship, the Madres de Plaza de Mayo . For years, the mothers demonstrated every Thursday in the busy square in front of the Argentine seat of government in Buenos Aires and demanded an account of the government. The participants were repeatedly threatened by the military and were victims of repression and arrests. One of the chairmen of the association later stated that at first they naively believed that the machismo widespread in Argentina would protect them and that they, as older women, would not be taken seriously by the military as a threat. The first kidnappings, especially the disappearance of the founder Azucena Villaflor de Vincenti without a trace , disappointed this expectation.

Number of victims

Estimates of the number of those permanently disappeared vary by source. In Chile, the so-called Rettig Commission in 1991 came to the conclusion that 2,950 people were murdered or permanently disappeared during the Pinochet regime. In Argentina, the murders of around a thousand people have been proven in detail; the number of people who disappeared permanently during the dictatorship - that is, murdered with great certainty - was given in estimates by the state commission of inquiry CONADEP as around 9,000 and by human rights groups as around 30,000 (see web links ). The Peruvian Commission for Truth and Reconciliation reported 69,280 persons who disappeared or were murdered by force between 1980 and 2000. Paramilitary groups and the government were responsible for around 41% of the victims, while the left-wing extremist organization Sendero Luminoso was responsible for around 54% of the murders. Human rights organizations estimate that around 45,000 people have disappeared in Guatemala.

In Guatemala, there was an almost permanent civil war in the second half of the 20th century , which killed a total of 150,000 to 250,000 people, mainly in massacres by the army or right-wing paramilitary troops of indigenous people.

According to estimates by human rights organizations, the total balance of Latin American repression policy in the 1970s and 1980s was around 50,000 murdered, 35,000 disappeared and 400,000 prisoners.

Legal processing

For a detailed discussion of the criminal aspects and the further development of international law, see the relevant sections in the article Enforced Disappearances .

Just a few months after the return to democracy, the newly elected President of Chile , Patricio Aylwin , set up a truth and reconciliation commission in mid-1990 . It was supposed to clarify the human rights violations committed between 1973 and 1989, including the political murders and the whereabouts of the disappeared (Desaparecidos). Since the influence of the military in the country was still great, Aylwin was forced to exercise restraint in his reappraisal policy; a criminal prosecution of the crimes could not have been conveyed to the armed forces.

The legal processing of these crimes continues in almost all affected countries to this day or has only been underway in some cases for a few years. This is due, among other things, to the fact that, when the affected countries transition to democracy, the perpetrators often passed protective amnesty laws (see, for example, the Argentine Final Line Act and the Pinochet case ), which the military had demanded as a condition for the transition to democracy. Some of these laws were only recently abolished, which opened up the possibility of prosecuting those responsible. For example, the first Argentine junta leader, Jorge Rafael Videla , was convicted again in December 2010 for numerous crimes committed at the time. The difficulties of prosecution have also helped international law to evolve accordingly. Such crimes can now be prosecuted internationally, see International Criminal Court . In particular, the systematic disappearance of people has been explicitly classified as a crime against humanity .

The Latin American human rights movement coined the term “enforced disappearance” in the 1970s. The adoption of the UN Convention against Enforced Disappearances , which was adopted by the UN General Assembly on December 20, 2006 and has been in force since December 23, 2010, is the result of more than 30 years of efforts by members of Desaparecidos and human rights experts, to implement a new criminal offense in international law. It was not least a question of extending the term victim to family members of disappeared people in order to secure certain rights for them.

The numerous people who have now been legally convicted or are still in court include various generals as well as the former head of the Chilean secret police Manuel Contreras and the Argentine officers Adolfo Scilingo , Miguel Ángel Cavallo and Alfredo Astiz .

Because of his various involvement in activities that violate human rights and his presumed role in Pinochet's military coup in Chile , several court summons were issued against Henry Kissinger in various countries, which he however never complied with. In 2001, the Brazilian government canceled the invitation to speak in São Paulo because it could not guarantee Kissinger's immunity. For example, a lawyer for a victim of the military dictatorship in Uruguay demanded the extradition of the former US Secretary of State and Nobel Peace Prize winner to the South American country. Kissinger is now threatened with prosecution because of (among other things) the above-mentioned incidents in several - also European - countries, which is why he rarely leaves the USA.

Disappeared Germans

Among the thousands of victims of the dictatorships were around 100 Germans and people of German origin. The best known of these were Elisabeth Käsemann , who works as a development worker and social worker in Buenos Aires, and the exchange student Klaus Zieschank . There are still several legal proceedings pending against those responsible for the military government, which the relatives in Germany brought. The legal processing is extremely difficult. The criminal liability of crimes against humanity committed abroad in Germany plays a role here . The trial of the murder of Käsemann even wrote legal history because the Federal Republic of Germany filed a lawsuit in Argentina against the law there on amnesty for the perpetrators.

A criminal complaint by the relatives of thirteen victims of German origin or German was rejected by the Nuremberg Higher Regional Court in 2004 , and the plaintiff's lawyer has lodged a complaint. One organization specifically dedicated to this topic is the coalition against impunity , which has been based in Nuremberg since 1997 .

Cultural processing

The subject of Desaparecidos has been dealt with in a large number of artistic works. For a complete overview, see the illustration in the article Process of National Reorganization . South American filmmakers in particular have been countering criticism from conservative circles to this day, who criticize the depictions of violence in scenes of torture as being exaggerated. This criticism is regularly countered with the argument that the films are only a reflection of the reality of that time, documented in detail.

Literature and theater

South America

- Ariel Dorfmann : Death and the Maiden (Spanish: La muerte y la doncella ), play, 1991.

- Paula Pérez Alonso : No sé si casarme o comprarme un perro . Tusquets Editores, Barcelona 1998, ISBN 84-7223-947-0 .

Movies

South America

- The Official Story (La historia oficial) is an Argentine film drama of directors Luis Puenzo and Jaoquin Calatayud from 1985 . The film is about a couple wholivein Buenos Aires with their adopted child . The mother discovers that her daughter could be the child of a desaparecido who was a victim of kidnappings during the Dirty War in Argentina in the 1970s .

- La noche de los lápices (“ The Night of the Pencils ”) by Héctor Olivera , Brazil 1986. Based on the book of the same name by María Seoane about a real event in Argentina in September 1976, which is reconstructed on the basis of the reports of Pablo Díaz, the only survivor could be.

- Desembarcos - there is no forgetting by Jeanine Meerapfel , Argentina / Germany 1986–1989.

- Junta by Marco Bechis , 1999. Buenos Aires at the time of the military dictatorship: the student Maria is kidnapped by the secret police in a disused car repair shop. There she meets Felix, her closed roommate, who is in love with her: he is the "interrogation" specialist. While this develops into a relationship of power, affection, torture and the will to survive, Maria's mother tries by all means to find her daughter. The director of the film was himself a victim of the dictatorship.

- Cautiva (in German: prisoners), 2005.

- Buenos Aires 1977 (orig. Crónica de una fuga) by Adrián Caetano , 2006. The true story of the football player Claudio Tamburrini , who was kidnapped and tortured in 1977 during the Argentine military dictatorship, but was finally able to escape.

Other countries

- Missing (Missing) by Constantin Costa-Gavras , 1981. Jack Lemmon plays an American entrepreneur who during a military coup supported by the United States goes in search of his idealistic, missing son. The plot is very closely based on the authentic story of the American journalist Charles Horman , who waskidnapped and murdered by the militaryshortly after the 1973 coup in Chile supported by the CIA .

- Salvador by Oliver Stone , 1986. James Woods depicts a photographer who visited the civil war-torn Latin American country El Salvador during the 1980sand was confronted with the atrocities there. The film is largely based on real events, the director vehemently attacked American Central America policy. In the absence of US funding, the film was financed with English capital. It grossed only about $ 1.5 million in US cinemas.

- Blue Eyes by Reinhard Hauff , 1989. Götz George plays a German businessman in Argentina who does business with the military. After his heavily pregnant daughter is arrested and killed, he learns that she still had the child - but it has disappeared.

- Marco - Über Meere und Berge is a German-Italian children's series from 1991 in which a 13-year-old Italian sets off for Argentina to look for his missing mother.

- Death and the Maiden (Death and the Maiden) by Roman Polanski , 1994. Sigourney Weaver , Ben Kingsley and Stuart Wilson in a drama about the meeting of a tortured woman with her alleged tormentor, after the end of military dictatorship.

- Imagining Argentina by Christopher Hampton , 2003. InBuenos Aires in 1976, Antonio Banderas , as a desperate father, follows the disappearance of his wife.

- Das Lied in mir by Florian Cossen , 2010. Jessica Schwarz embodies a young woman who was kidnapped and adopted as a toddler by a German couple ( Michael Gwisdek plays the father) after her birth parents disappeared as victims of the Argentine military dictatorship.

music

The Argentinian musician Charly García caricatured the military rulers as “dinosaurs” in his song “Los Dinosauros” (1983) . Translated, the refrain reads: "Your friends, your neighbors, the people on the street can disappear - but the dinosaurs will disappear."

In his 1984 album "Voice of America" , Little Steven treated the subject in the song "Los desaparecidos" .

The Panamanian salsa singer Rubén Blades deals with the subject in his song "Desapariciones" from 1984. The Mexican band Maná covered the song in 1999 at their MTV Unplugged concert.

In their 1987 album The Joshua Tree , the band U2 honored the commitment of the relatives of the disappeared in Latin America with the song Mothers of the Disappeared . In the same album, in the song Bullet the Blue Sky, she massively criticized the US support for the military dictatorship in El Salvador.

For his song " They Dance Alone " from 1987 (in honor of the mothers of the victims of the Chilean Pinochet regime) Sting was honored in 2001 with the Gabriela Mistral Prize for Culture.

See also

- Argentine military dictatorship (1976-1983)

- Black Site

- History of Argentina

- History of Chile

- History of Guatemala

- International Day of the Disappeared

- Nunca más

- Death flight

- Death squad

- Disappearance

literature

- Willi Baer , Karl-Heinz Dellwo (Ed.): The Battle of Chile, 1973–1978. (Library of Resistance, Volume 7), Laika-Verlag , Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-942281-76-8 .

- Willi Baer, Karl-Heinz Dellwo (ed.): That you are silent for two days under torture. (Library of Resistance, Volume 8), Laika-Verlag, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-942281-77-5 .

- Willi Baer, Karl-Heinz Dellwo (Ed.): Panteón Militar - Crusade against Subversion. (Library of Resistance, Volume 9), Laika-Verlag, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-942281-78-2 .

- Willi Baer, Karl-Heinz Dellwo (Eds.): Dictatorship and Resistance in Chile , Laika-Verlag, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-942281-65-2 .

- David Becker: Without hatred, there is no reconciliation. The trauma of the persecuted. Kore Edition, Freiburg 1995.

- CONADEP : Never again! An account of kidnapping, torture and murder by the military dictatorship in Argentina. Co-edited by Jan Philipp Reemtsma , Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 1987 - no longer available ISBN 3-407-85500-1 .

- CONADEP: Nunca más - Never Again: A Report by Argentina's National Commission on Disappeared People. Faber & Faber, December 1986, ISBN 0-571-13833-0 .

- Christian Dürr: "Disappeared". Persecution and torture under the Argentine military dictatorship (1976–1983). Metropol, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-86331-279-4 .

- Gustavo Germano: Disappeared. The photo project “Ausencias” by Gustavo Germano, with texts on the dictatorship in Argentina 1976–1983 , translated from Spanish by Ricarda Solms and Steven Uhly, Münchner Frühling Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-940233-43-1 .

- Roland Kaufhold : No reconciliation without hatred: a conversation with David Becker , psychosocial No. 58 (4/1994), pp. 121–129. Online at hagalil.de

- Ana Molina Theißen: La desaparición forzada de personas en America Latina ( Memento of July 8, 2002 in the Internet Archive ) .

- Horacio Verbitsky: The Flight. Confessions of an Argentinian Dirty Warrior. New Press, August 1996, ISBN 1-56584-009-7 .

Legal Aspects

- Andreas Fischer-Lescano : Global Constitution. The justification for the validity of human rights. Velbrück, Weilerswist 2005, ISBN 3-934730-88-4 .

- Kai Cornelius: From disappearance without a trace to the obligation to notify arrests. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag 2006, ISBN 3-8305-1165-5 .

- Christoph Grammer: The fact of the disappearance of a person. Transposition of a figure under international law into criminal law. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11998-3 .

Web links

- Nunca más (Never again) - Report of the Argentine commission of inquiry CONADEP on the crimes during the dictatorship, with detailed figures and the like. a. on disappearances and child abductions, with hundreds of testimonies (Spanish / English)

- desaparecidos.org - Project website of an association of various human rights organizations to commemorate the disappeared

- How a German exchange student disappeared ( Memento from August 16, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) - text of the criminal complaint against Argentine generals for the kidnapping and death of Klaus Zieschank in Argentina in 1976

- The Coalition Against Impunity ( Memento from June 23, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) The coalition is an association of 15 human rights and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and institutions of the Protestant and Catholic Church, which are committed to ensuring that truth and justice for those during the Argentine military dictatorship 1976–1983 missing Germans is found.

- International Convention for the Protection against Enforced Disappearances, February 6, 2007

- Sylvia Karl: Convention against Enforced Disappearances , in: Sources for the History of Human Rights, published by the Working Group on Human Rights in the 20th Century, May 2015, accessed on January 11, 2017.

- Daniel Stahl: Report of the Chilean Truth Commission , in: Sources for the history of human rights, published by the Working Group on Human Rights in the 20th Century, May 2015, accessed on January 13, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b "Operation Condor" - Terror in the Name of the State. ( Memento from September 12, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) tagesschau.de, September 12, 2008.

- ↑ The Current Role of Military Power in Latin America. ( Memento from October 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Invitation text for the day seminar of the educational institute of the Heinrich Böll Foundation Berlin in cooperation with the FDCL, September 8, 2007.

- ↑ a b c d Argentine Military believed US gave go-agead for Dirty War. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book, 73 - Part II, CIA Confidential Documents, published 2002.

- ↑ Steffen Leidel: Notorious ex-torture center opens to the public. In: Deutsche Welle. March 14, 2005, accessed December 13, 2008 .

- ↑ word-travel.com

- ↑ Martin Gester: The land of the "Desaparecidos". Terror and Counter Terrorism in Argentina . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of June 2, 1978, p. 10.

- ↑ Christiane Wolters: Ex-officer in court for "death flights" . Deutsche Welle , January 14, 2005.

- ^ Horacio Verbitsky: The Flight: Confessions of an Argentinian Dirty Warrior. New Press 1996, ISBN 1-56584-009-7 .

- ^ Marie-Monique Robin: Death Squads - How France Exported Torture and Terror. (No longer available online.) In: Arte program archive . September 8, 2004, archived from the original on July 21, 2012 ; accessed on March 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Werner Marti: Videla convicted of child robbery. Argentina's judiciary speaks of the systematic appropriation of babies by the military . Neue Zürcher Zeitung online, July 7, 2012

- ^ Benjamin Schwarz: Dirty Hands. The success of US policy in El Salvador - preventing a guerrilla victory - was based on 40,000 political murders. Book review on William M. LeoGrande: Our own Backyard. The United States in Central America 1977-1992. 1998, December 1998.

- ↑ Guatemala. Proyecto Desaparecidos, accessed on October 23, 2008 (it is unclear whether this figure is part of the total number of civil war casualties, but this is more likely).

- ^ Daniel Stahl: Report of the Chilean Truth Commission. In: Sources on the history of human rights. Working Group on Human Rights in the 20th Century, May 2015, accessed on January 11, 2017 .

- ↑ Sylvia Karl: Convention against Enforced Disappearances. In: Sources on the history of human rights. Working Group on Human Rights in the 20th Century, May 2015, accessed on January 11, 2017 .

- ↑ gwu.edu

- ↑ Christopher Hitchens: The Case Against Henry Kissinger . In: Harper's Magazine . February 2001 ( icai-online.org ( memento of August 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive ; PDF) - pages 2/3 and penultimate page).

- ^ Criminal charges against Argentine generals because of the death of Klaus Zieschank. ( Memento of June 29, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) March 20, 2000, www.menschenrechte.org

- ^ A surprising turning point in the Elisabeth Käsemann case. German federal government sues in Argentina: pardon laws are unconstitutional . Research and Documentation Center Chile-Latin America e. V. , December 10, 2001.

- ↑ Complaint against the notification of employment by the Nuremberg-Fürth public prosecutor's office. ( Memento from June 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) March 7, 2006, www.menschenrechte.org

- ↑ meerapfel.de