The story of Sinuhe

| Sinuhe in hieroglyphics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surname |

Sa-nehet S3-nh.t Sinuhe (son of sycamore ) |

|||||

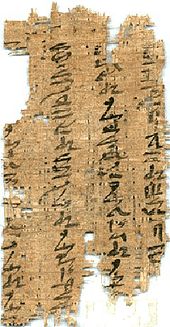

| Beginning of the Papyrus Berlin 3022 with the Sinuhe story in an edition by Georg Möller | ||||||

The story of Sinuhe is an original untitled work of ancient Egyptian literature from the beginning of the 12th dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (approx. 1900 BC). The unknown author of the poem describes in the form of a first-person story the presumably fictional life story of the court official Sinuhe, who panics after the death of King ( Pharaoh ) Amenemhet I and finally settles in the Palestine region after an adventurous escape . But in old age he is plagued by homesickness. In fact, Sesostris I asked him .to return home, having recognized his innocence in the death of his father Amenemhet. Sinuhe then returned to Egypt and was received there with all honors.

The story has a strong respect for I. Royal Court of Sesostris and partly as a kind of propaganda considered that the loyalty to the king stressed. In addition, the identity as an Egyptian , especially in the mirror image of foreign countries, and the desire to be buried as an Egyptian seem to play a special role.

Most Egyptologists agree that this is a masterpiece of Egyptian literature and the most famous story from ancient Egypt is, for Richard Parkinson , however, at the expense of other, less accessible works. It was read and circulated long after it was written. In modern times it found its way into literature and the medium of film .

Tradition and dating

The narrative is currently transmitted in 36 known manuscripts (8 papyri and 28 ostraca ). All come from the Middle or New Kingdom and were written in hieratic script , the italics of hieroglyphics and the Middle Egyptian language . Mostly it is translated into hieroglyphics using transcriptions . Roland Koch's standard edition has been the standard edition since 1990 .

Time of origin

The plot of the Sinuhe story ends in the late reign of Sesostris I (ruled approx. 1956 to 1910 BC), which means that the earliest possible date of origin ( terminus post quem ) is given. The oldest surviving manuscript (Papyrus Berlin 3022) dates around 100 to 150 years later, in the second half of the 12th dynasty. This means that the latest possible creation time ( term ante quem ) is given. For reasons of content, it is generally assumed that the work was created immediately after the events described, possibly during the reign of Sesostris I or shortly afterwards.

Middle Kingdom manuscripts

The most complete and probably oldest surviving manuscript of the Sinuhe story is the Papyrus Berlin 3022 (abbreviated B ). It was probably found in a private Theban grave and dates to the second half of the 12th Dynasty; on the basis of a prescription at the beginning of the letter, the reign of a king by the name of Amenemhet is assumed, with which Amenemhet II and Amenemhet III. would come into question. The Papyrus Berlin 10499 (abbreviated R ) also comes from Thebes, from a grave near the later Ramesseum . Taken together, the two papyri B and R offer the text from beginning to end, and the narrative is usually quoted according to their line and column division (R1 – R24, B1 – B311). B and R are more than a century younger than the first draft and differ somewhat from this (no longer preserved) original text .

Two papyrus fragments with only a few lines of text presumably also date to the late 12th dynasty. These come from Al-Lahun , which is located at the eastern entrance of the Fayyum Basin and was in the immediate vicinity of the government center of the Middle Kingdom. A large part of these Lahunpapyri discovered Flinders Petrie 1888-89, including probably also Papyrus UC 32106C, the location of which was not precisely noted, but which probably belonged to an archive with literary and non-literary texts. The text of the Sinuhe is on the verso ; the recto contains an unknown, probably also literary text. Papyrus UC 32773 (also Papyrus Harageh 1, abbreviated H ) was found in the necropolis of Harageh by Reginald Engelbach and may come from a grave.

Papyrus Buenos Aires (abbreviated BA ), another fragment with the narrative, can also be dated paleographically to the 12th dynasty, but nothing is known about its origin and the circumstances in which it was acquired.

New Kingdom manuscripts

The very fragmentary Papyrus Moscow 4657 (abbreviated G ) only contains passages from the beginning of the story. It was allegedly bought around 1900 by the Russian Egyptologist Vladimir Semjonowitsch Golenishchev in Luxor, but nothing is known about the circumstances of the find . According to content criteria, an origin from the north was assumed, for example from Memphis , but the similarity to the papyri from Deir el-Medina suggests an origin from Thebes . Paleographically, it can be dated to the late 18th or 19th dynasty.

Another papyrus of the New Kingdom is the Turin Papyrus CGT 54015, which is still unpublished to this day.

The 28 ostraka known so far probably come mainly from the school operation of the New Kingdom in Thebes West, in the writing school of the necropolis workers of Deir el-Medina, although some of them were found in graves, including two in the grave of Sennedjem . They probably all date to the Ramesside period . Most of them contain short writing exercises, mostly from the beginning of the narrative, in which the students should primarily learn the calligraphy and the structure (rubra and verse points) of a classical text in classical language .

Only the Ashmolean Ostrakon (abbreviated AOS ) is longer and offers about 90% of the narrative on its front and back. It may have been kept in an archive as a template for the students' writing exercises.

Only the ostracon Senenmut 149 (abbreviated S ) comes from another place in Thebes-West, namely from the grave of Senenmut ( TT71 ) near Deir el-Bahari , and thus dates to the time of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. (early 18th dynasty). In addition, there are no direct witnesses to an occupation with the text in the 18th dynasty, but this is probably due to the tradition. Quotations in the funerary inscriptions of this dynasty leave no doubt that the story was read intensively at this time, and the Ashmolean Ostrakon also contains traces of an editing that must have occurred under Akhenaten's rule .

Transmission into the late period

Ludwig D. Morenz sees the story as a prime example of the integration of different themes and styles and as a veritable “book edition” that was probably already kept in private libraries in the Middle and New Kingdoms. Thus it was part of the general educational property. Eberhard Otto speaks of a “didactic piece”, an amusing “historical” story that basically always remained topical and whose language was always useful to learn as a prime example of “classical” forms .

The many ostracas with quotations from literary texts that were found in Deir el-Medina are traditionally considered to be writing exercises by students. According to another opinion, they are texts that were prepared and preserved by educated workers. However, it is unlikely that such widely cited texts as the book Kemit were read out of mere interest in literature. In addition, the literary texts were sometimes so badly distorted as if they had not always been understood by the writers (or students).

Quotes and allusions in royal and private inscriptions of the second and first millennium BC BC show that the popularity was neither limited to the scribe nor to the New Kingdom. Although no other manuscripts have come down to us for the period after the New Kingdom, the tradition of other “classical” works up to the 27th Dynasty suggests that Sinuhe continued to be copied. The victory stele of Pianchi from the Kushite 25th dynasty contains certain allusions to the Sinuhe story. The latest known quote probably comes from the biography of Udja-Hor-Resnet, who lived during the Persian period (525–401 BC):

"The barbarians (ḫ3stjw) brought me from country to country (m ḫ3st r ḫ3st) and escorted me to Egypt, as the Lord of the two countries had ordered."

contents

At the beginning, Sinuhes name and title are mentioned in the style of an autobiographical grave inscription , which he bears at the end of his life: The count and prince , the royal lower Egyptian seal keeper and only friend (of the ruler), the judge and administrator in the countries of the Asians, the real one Acquaintance of the king he loves, the henchman, Sinuhe (son of the sycamore ) . The actual narrative begins with the death of King Amenemhet I on the 7th Achet III in the 30th year of reign, describing the great grief of the people, but not the reason for the sudden death, but the description fits well with the teaching of Amenemhet , after Amenemhet I. died in an assassination attempt in the harem .

The "Crown Prince" Sesostris I is on his way back from a campaign in Libya , which he led as commander, when messengers reach him with the news of his father's death. Without hesitation and without informing his army, Sesostris rushes to the residence to arrange the succession. When the news of death was sent to the other royal children as well, Sinuhe found out about this by chance and ran away. He describes his dismay and panic in great detail without giving an exact motive for his hasty flight.

The escape leads him through different places and countries. He reaches the border with the Middle East near Wadi Tumilat , where he initially hides in a bush for fear of being seen by a guard (guard?) Until he dares to cross the border secretly at night by hitting the so-called "Walls of the Ruler." “Overcomes. A little later he impressively describes the experience of his near death, when he almost died of thirst and was rescued by the Bedouins at the last moment .

Sinuhe then travels to Byblos until Amunenschi , the ruler of Upper Retjenu (mountainous country of Syria-Palestine), takes him in. When Amunenschi asks him about the reason for his flight, Sinuhe m jwms , as he calls it , answers in untruth or half-truth and says that he did not know what brought him to this strange land, it was like a plan of a god . When Amunenschi inquires about the situation in Egypt, Sinuhe begins a eulogy on King Sesostris, in which he describes him as a heroic warrior, fearless of foreigners and incredibly popular in his country. Amunenschi then shows him the reality of his situation: Well, Egypt is good because it knows that it is powerful. See, you are (but now) here, you are with me. Good is what I do to you. Amunenschi proves to be generous, appoints him prince and commander of the army, gives him his daughter as his wife and a piece of fertile land in the border area called Jaa, which Sinuhe describes as a kind of "milk and honey". So Sinuhe starts a family and spends many years in this country.

A central incident and turning point in the story is Sinuhes duel with a local challenger, the strongman of Retjenu , a nameless man who has already defeated all of Retjenu. He plans to rob Sinuhe and challenges him to a fight. Sinuhe defeats the strong man of Retjenu, which brings him even more wealth and prestige. Ironically, this triggers an inner conflict in Sinuhe and he suddenly feels homesick for Egypt and prays to the gods: I'm sure you will let me see the place where my heart dwells! What is greater than my corpse being united with the land in which I was born?

Almost miraculously, Sinuhes prayers are answered and he receives a letter from King Sesostris, who asks him to come back to Egypt, since he had done nothing bad. In his reply, Sinuhe repeatedly affirmed his innocence and that he did not intend to flee and did not flee of his own accord, but that it took place in a dream-like state, as if a god had caused it.

Sinuhe then travels south on the Horus Way and arrives at the capital Itj-taui . When the king receives him for an audience in the palace, he throws himself on the floor in front of it and has a death-like collapse: I was like a man who is gripped by the twilight, my soul was gone, my body was exhausted, my heart, it wasn't in my body. I <not> knew how to distinguish life from death. Sinuhe is lifted and the queen and the royal children are called, who again ask for mercy for Sinuhe, whereupon the king grants this and causes Sinuhe to take up the position of court official again. The king also lets him build a stone pyramid in his pyramid field , which is equipped with a statue covered in gold, among other things.

Form and style

There is broad consensus among Egyptologists that the story is written in verse (rather than prose ), but its character is interpreted differently. Gerhard Fecht has mainly structured the middle part according to his rules of metrics . A more promising way seems to be to divide the verses into units of meaning. Miriam Lichtheim sees the parallelism membrorum as a fundamental principle of form, as in biblical literature . According to John Foster, the completion of parallelism mostly extends to a pair of verses that he calls the thought couplet . In this, the thought of a sentence or part of a sentence is repeated or expanded in other words in the following.

The following text example (description of the land of Jaa) illustrates the division of the verses into thought couplets, as done by John Foster:

- It is a good country, Jaa is its name,

there are no equals on earth. - There are figs in it and grapes

(and) more wine than water. - Its honey is plentiful, its moringa oil

trees abundant (and) all fruits are on its trees. - Barley is in <ihm> and emmer,

there is (also) no end to any cattle. - What was due to me was also plentiful,

along with what came in because of my popularity.

Jan Assmann has succeeded in working out a subdivision scheme that is superordinate to the verses on the basis of the rubrics that have been handed down in several manuscripts . Accordingly, the text consists of 40 pericopes (larger sections of verses) of various lengths, the boundaries of which are determined by rubrics. It can also be broken down into 5 sections, each with 8 pericopes: I. The escape, II. Sinuhe and Amunenschi, III. The turning point, IV. The correspondence between the king and Sinuhe and V. Homecoming. Assmann reflects on the meaning of this division into 5 sections:

“Sections I, III and V advance the narrative, according to the universal tripartite division of each story into arché ( exposition ), peripateia (turn, complication) and lysis ( dissolution ) in three clearly separated steps. Sections II and IV hold up the narrative and sound out the meaningful horizon of the event in reflective pericopes designed as (oral and written) dialogue. I and V stand in contrast to one another: languishing flight and exclusion from the community, honorable return and reintegration into Egyptian society. The middle section III contains in its middle pericope, which is emphasized by its excess length, the climax and turning point of the story: the duel with the "strongman of Retenu". "

Historical report or literary fiction?

Outside of the literary framework, no evidence of the existence of Sinuhes has yet been found. Although the name "Sinuhe" is used several times in the Middle Kingdom, the Sinuhe of this story is historically inconceivable. Nevertheless, it has always been assumed that this is a historical personality, as the story is designed in the style of an autobiographical grave inscription . This genre originated in the burial of civil servants in the Old Kingdom (around 2500 BC) and consisted on the one hand of the "career biography", in which the civil servant's career can be read, and the "ideal biography" in which the deceased boasted of his good deeds and the is based on the norm of Maat : In the identity presentation of the ideal biography, the individual does not appear as an individual , but as a perfect building block in the order that is meant by the term Maat. Since the end of the Old Kingdom (with the collapse of the royal central authority) personal achievement has come to the fore in autobiographical reports. They are expanded and, in addition to the “ wisdom discourse of the ideal biography”, more and more historical details appear, so that they come ever closer to the literary texts.

Most recently, in 1996, Kenneth A. Kitchen suggested that the story was based on a real autobiography, which was copied from the tomb of Sinuhe in the pyramid district of Sesostris on papyrus and then circulated. Typical elements of the genre of the autobiographical grave inscription are the introduction with titles , name and "He says", followed by a first-person narration, as well as the embedding of other literary forms such as the royal hymn and the king's letter. According to Kitchen, the highly specific references to real contemporary rulers in Egypt and abroad place the story alongside real adventurers like Harchuf and, unlike the fictional works, there is no once-once-upon-a-time element, no anonymity of the main characters, no vagueness about places and places no fantasies or magical miracles.

However, with other genres such as lamentation, private letter and cult hymn and in scope, style and intention, the narrative goes well beyond the form of the autobiography, it is about twice as long as the autobiographical inscription of Khnumhotep II in Beni Hasan , the longest the Middle Kingdom. According to Jan Assmann, the story is a copy of an autobiographical grave inscription in order to make use of the literary possibilities inherent in this genre. Accordingly, the grave is in many ways the “preschool” of literature. The writer of the literary text as a "literary fact" orients himself on the model of the autobiographical grave inscription as an "initial type" or an "extra-literary fact".

In general, for Antonio Loprieno it is a sign of fictional creation when a text appears outside of its given framework - for example, with Sinuhe an autobiographical text appears outside the grave. Bill Manley thinks that the question of whether Sinuhe arises from poetry or from the truth is not so important: If Sinuhe actually existed, then he has been so literally transfigured from a literary point of view that only one character is left of his real life .

Historical background

The plot of the Sinuhe story takes place at the beginning of the ancient Egyptian 12th dynasty and has often been used as a historical source for this time. This is not always unproblematic, but neither does it float in a historically vacuum and often coincides with other sources such as the teaching of Amenemhet.

The early 12th dynasty

Towards the end of the Old Kingdom, the power and independence of the civil service increased and the rule of the king decreased more and more. There was a gradual loss of the king's divine dignity, and the loss of central royal authority (around 2200 BC) finally ushered in the First Intermediate Period . This was a deep spiritual and political turning point in Egyptian history. Only Mentuhotep II. Could the central power around 2025 BC. And the Theban 11th dynasty became the new imperial dynasty. After this rather short-lived dynasty, Mentuhotep IV was followed by Amenemhet I as the first king of the 12th dynasty.

Efforts were now being made to re-create a kingdom based on the example of the Old Kingdom, which demanded the absolute loyalty of the officialdom and to tie in with a time when the kingdom was still an unrestricted divine kingdom. So the pyramids were resumed as a tomb shape and the residence was relocated to Itj-taui near Memphis, the residence of the Old Kingdom.

A major problem of this new dynasty was the question of legitimation as king, since Amenemhet I was not of royal descent. He began his career at the court of Mentuhoteps IV and rose to vizier under this . It is possible that Mentuhotep IV had left no successors, so that Amenemhet I ascended the throne as the highest-ranking man in the country - certainly not without resistance.

Co-regency of Amenemhet I with Sesostris I.

According to some Egyptologists, Amenemhet I installed his son Sesostris I as co-regent in his 20th year of reign and they ruled together on the Egyptian throne for ten years. The question of coregences in ancient Egypt in general and that of Amenemhet I with Sesostris I in particular is one of the most controversial questions in Egyptology. According to the theology and “royal ideology” of the ancient Egyptians, the king is a singular, divine being and can therefore only be presented as the sole ruler. He reigns as the embodiment of Horus on earth and, after his death, merges with Osiris, the ruler of the underworld. It is hardly compatible with this concept that two Horus falcons suddenly rule. On the other hand, for pragmatic reasons, co-membership certainly had many advantages:

“A change of throne, and thus a change of power, in Egypt, as in other oriental monarchies, must have been staged very often through harem intrigues , murders and coups , undoubtedly much more often than the few times our sources say or suggest such things. [...] Violent action is likely to have been the rule rather than the exception in connection with the change of throne. The early coronation of the designated successor, while the old king was still alive, offered a certain degree of security against these dangers.

As evidence for or against such coregency, some passages of the Sinuhe narrative were also cited. At the beginning of the report on the Libyan campaign (R 12-13), the name Sesostris' I is written in a cartouche that usually surrounds the name of a king. Jansen-Winkeln sees this as proof that Sesostris was already ruler at this point in time. In the opinion of Claude Obsomer, however, this is an anachronistic name, since the story was written at a time when Sesostris was king. A little later (R 18), Sesostris is again only referred to as the “king's son” (s3 njswt) , which, according to Obsomer, proves that he was not yet king. For Jansen-Winkeln, however, only the function as a son is relevant at this point, as the death of the father is reported.

Günter Burkard uses another passage from the eulogy on Sesostris I as an argument against coregence:

“It is he who subjugated the foreigners while his father was in his palace. He reports to him that his orders are being carried out. "

In his opinion, it is hardly possible for a coregent to carry out orders and Sesostris is only described here in his role as son and general.

The assassination attempt on Amenemhet I.

The account of the death of Amenemhet I at the beginning of the Sinuhe story recalls the teaching of Amenemhet . In this Amenemhet reports in the style of a posthumous "will" how he fell victim to an assassination attempt:

“It was after supper and night had come.

I gave myself an hour of refreshment

by lying on my bed because I was tired

and my heart began to indulge in my sleep.

The weapons were turned against me for my protection

while I acted like a snake in the desert.

I woke up to the fight by being with myself immediately

and found it to be a scuffle between the guards.

I hurried, weapons in my hand,

and so I drove the cowards back into (their) lair.

But there is no one who can fight alone,

and a successful deed cannot be achieved without helpers. "

It is also reported that the attack occurred when Amenemhet was without Sesostris, which is reminiscent of the Libya campaign mentioned in Sinuhe. It also goes well with the fact that Sinuhe, a harem official, is fleeing because Amenemhet was apparently the victim of a harem conspiracy:

“Had women ever raised troops?

Are rebels raised in the palace? "

However, the Amenemhet's teaching does not report the outcome of the assassination attempt. This led to different views among Egyptologists, especially in connection with the discussion about the coregences.

According to one opinion, Amenemhet did not die by an assassination attempt in his 30th year of reign, but escaped such an attack about 10 years before his (natural) death and as a consequence established the office of co-ruler for his son Sesostris. Accordingly, Amenemhet commissioned the teaching and it describes a "what-if" situation to justify the position of co-ruler. According to Jansen-Winkeln, the Sinuhes escape does not contradict it. He flees because of an error or hearing defect with unrest, in the further course of the story he asserts several times that nothing had happened and only "his heart" had misled him .

According to another view, the story of Sinuhe and the teaching of Amenemhet both portray the historical circumstances of Amenemhet's death. The doctrine was commissioned by Sesostris after Amenemhet's death in order to legitimize his succession.

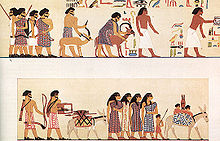

Palestine in the 2nd millennium BC Chr.

The Sinuhe narrative is an important Egyptian source for the political situation in Palestine in the early 2nd millennium BC , along with the outlawing texts . After the collapse of the urban centers in the final phase of the Early Bronze Age in this region - presumably mainly because of supply problems - city-states or permanent settlements had already emerged at this time, but the nomadic way of life, the way of life of pastoral nomadism, also continued to exist (Wandering grazing). One might imagine tribes next to cities as a model, ie a juxtaposition of stateless nomadic ways of life and state urban forms of rule . At least some of the Amurites found themselves in the process of settling down and urbanization.

Sinuhe also lived between roaming nomads and rulers of clearly defined areas. For example, Byblos was a city-state of some importance, but the outlaw texts also speak of the tribe of Byblos. Sinuhe lived in a tent and the description of the strong by Retjenu also shows Bedouin coloring. Apart from Byblos, the author of the Sinuhe narrative makes no mention of any cities, although urban culture was just beginning to blossom anew at the time the narrative was composed. According to Ludwig Morenz, this was due to the fact that the contrast between Egypt and Palestine was emphasized even more, in which foreign countries are portrayed as unculture . To do this, they resorted to the historical and local palette of Palestine.

For the first time the term Ḥq3-ḫ3swt ("ruler of foreign lands") appears in the Sinuhe story (Sinuhe B98), which is commonly called Hyksos . At the time of the Middle Kingdom, this term stood for a specific group in the population of the Palestinian region. Later it meant kings of Asian origin who lived in Egypt from around 1650 to 1542 BC. Exercised a foreign rule. According to Ludwig Morenz, the "rulers of the foreign countries" in the Sinuhe story are established rulers who differ from the wandering nomads at the time of settling in the Palestinian region.

Interpretations

Political Literature

In 1956, Georges Posener worked in a subtle analysis of a group of works from older, “classical” literature as political literature, “as literature for the purpose of legitimizing the young 12th dynasty in need of legitimation” .

Thus, at the beginning of the 12th Dynasty, the kings were faced with the difficulty of restoring the prestige of the office and establishing a kingship that, as in the Old Kingdom, was determined by the absolute loyalty of the subjects. That is why the texts of this dynasty were sometimes referred to as "propaganda literature", as a medium for propaganda purposes, which, among other things, repeatedly emphasized the most golden of all virtues: loyalty to the king.

Posener used the term “ propaganda ” with extreme caution, aware of how loaded and misleading it is. William Kelly Simpson uses the term "maintenance propaganda", which is used to maintain the status quo of the political and religious situation and not to change it. The majority of these texts were written with the intention “to show the present as the best of all worlds on the timeless foil of jzf.t vs. m3ˁ.t 'chaos vs. order'” .

In this context, Georg Posener found a strong reference to the royal court of Sesostris I for the Sinuhe story as well, but was reluctant to judge whether it was a political propaganda work. given a lot of space, and it arises from the perimeter of the courtyard, but one cannot say whether it is, strictly speaking, a work of political propaganda. The author expresses his beliefs and feelings without particular exaggeration, authentically and without intentional tricks aimed at influencing the reader. According to Posener, it is rather the sincerity and warm-heartedness of the writer that make the narrative a work that is suitable for addressing royalty among the readership.

Interpretation inherent in the work

After Georges Posener's groundbreaking analysis of the political tendencies and thus the extra-literary purpose of the text, John Baines noted in 1982 that, despite the volume of what he wrote about Egyptian literature, there were few possible approaches to it that are widespread in other areas of literature were needed.

He subjected the Sinuhe narrative in sections and from different perspectives to an in-depth interpretation inherent in the work . He saw the text as an independent work of literature, more or less detached from temporal, geographical and political references, but also emphasized that this approach is not exclusive, but rather stands alongside many others.

In summary, Baines came to the following verdict:

“Scrutiny of the narrative structure and the presentation of character in Sinuhe does identify considerable complexity, analogous with the richness of the text in style and vocabulary; it also brings out the relationship of the text with Egyptian values. Techniques of analysis that are applied to western literature seem to yield results with Sinuhe , but reveal alien preoccupations and emphases, as is only to be expected. Such analyzes do not seek to discover a single, correct understanding or author's intention in a text, but to deepen our comprehension of its meaning. "

“A close examination of the narrative structure and the representation of the characters in Sinuhe identify a considerable complexity, analogous to the richness of the text in style and vocabulary; it also brings out the relationship of the text with Egyptian values. Analytical techniques used in Western literature seem to give results in Sinuhe , but reveal foreign concerns and focuses, as is only to be expected. Such an analysis does not seek to determine a single, correct understanding or intention of the author, but to deepen our understanding of its meaning. "

Dispute literature

According to an older view, the literature on dispute is about texts which, after the collapse of the Old Kingdom, attempted to cope with the crisis of the first interim period. For example, the Ipuwer's warning words describe in many expressions the catastrophic situation in which the country finds itself. Recent research shows a tendency towards late dating of the dispute literature, earliest to the late 11th dynasty, but more likely to the 12th dynasty. The texts therefore do not describe a historical situation. Dorothea Sitzler comes to the conclusion that at no point are authentic testimonies to a personal extreme situation, but part of a literature developed for wisdom teachers to reflect on the role of wisdom and the wise in the world.

The Sinuhe narrative is at certain points in the discourse of the literature on dispute. She, too, addresses the question of the relationship between divine power of fate ( determinism ) and the individual's freedom of will. Sinuhe justifies his actions at various points with divine providence and inspiration and a god drove him to flee, which he also puts forward as an argument in order to be accepted again at the court of Sesostris I. For Winfried Barta, the question of human freedom and determination has resulted in a compromise: With Sinuhe there is neither absolute determination of human beings by God, nor absolute freedom of will.

According to Wilfried Barta, the topos of the “reproach against God”, as found in the literature on dispute, is only unspoken and hidden in the Sinuhe story, as God is ultimately made responsible for Sinuhe's flight and years of stay abroad. For Elke Blumenthal, the text does not raise a “reproach against God”, but pragmatically demonstrates how the individual (civil servant) can prove himself in the skill assigned to him and influence it by turning directly to God .

International experience

The sedentary Egyptians migrated only very involuntarily. The image of the clerk in the safe office was considered ideal. The story of Sinuhe also shows how the wanderer, from an Egyptian perspective, always leads an existence on the edge, outside the ordered world and always in danger of losing his roots . The narratives of the Middle Kingdom clearly contrast between “Egypt” and “abroad”. Most striking is the distinction between the center, often identified with the royal residence, and the periphery , the place where the protagonist experiences a psychological and intellectual transition.

Antonio Loprieno in particular emphasized the important role played by the size of the foreign country in the narrative, which is used to experience foreignness and to make self-determination. Topical statements about foreigner characters form a thematic context, a reference scheme, on the basis of which the literary process of mimesis undertakes a cultural confrontation with the other.

Accordingly, Sinuhe is at the beginning of a series of such realistic travel stories , such as the story of the shipwrecked man , the travelogue of Wenamun and the Odyssey of Wermai . He goes into exile voluntarily in order to go through a process of becoming conscious and becoming human over the course of several years in the mirror of the other himself, in the mirror of the foreigner figure Amunenschi, and to track down his own Egyptian identity . At the end of this international experience there is the realization that his existence can only lie in the role of the "Egyptian".

Gerald Moers goes even further in the interpretation and interprets Sinuhe's journey as a crossing of boundaries. Sinuhe must transcend the boundaries of Egyptian norms and break away from the requirements of a just way of life in the Egyptian sense according to the Maat concept: Both the Maat model and the concept of identity linked to it are suddenly in the "horizon of unfamiliar assignment" and in this way become through the hero can be questioned individually and the other world (abroad) becomes a mirror of one's own world (Egypt). These two worlds are so clearly differentiated from each other in the story that the transition from one to the other can only be experienced as a death-like dream state and the self-experience takes place in a dream-like state.

This newer interpretation emphasizes the fictional status and the cultural function compared to the political intention. The creation of possible or even alternative worlds contributes to the security of the readership's identity.

Individual questions

Reasons for Sinuhe's Escape

The description of the escape breaks the classic pattern of the autobiography and is the semantic cause of the formal complexity of the work. This sudden event frightens the modern reader and the "riddle" of flight, which, according to Parkinson, makes Sinuhe the Hamlet of Egyptian literature, is the subject of much Egyptological research.

The reasons for Sinuhe's escape are not given and remain in the dark. Sinuhe searches for a rational explanation for this in various passages, but he always comes to the conclusion that he does not know it. The escape was not of its own accord, but in a dream-like state, like a plan of God . However, he also admits that he told Amunenschi about his motives in untruth or half-truth, which suggests that he deliberately withholds the reasons or does not describe them with complete openness. In addition, he asserts that his escape was not due to fear, but his behavior expresses the opposite: During his escape he avoided inhabited places and even the appearance of isolated people on the way frightened him.

The harrowing event that led to his escape was probably an assassination attempt on King Amenemhet I. Perhaps Sinuhe was connected to the circle at court that was responsible for the events and rightly feared for his person. His situation is undoubtedly characterized and conditioned by the fact that he was one of the main characters in the princess' harem, but a harem conspiracy can rightly be suspected .

A. Spalinger does not believe that Sinuhe was involved in any conspiracy. In his opinion, the simplest solution is that Sinuhe expected violent unrest in the residence, a worrying situation that could have led to his death and that he is fleeing cowardice .

Whether Sinuhe was involved in a conspiracy or not depends crucially on the translation and interpretation of the word w3 (.w) in line R 25, in which messengers deliver the news of Amenemhet's death to the royal children and Sinuhe overhears it by chance:

“ I was close to a conspiracy. or: I was near far away. "

Either it is expressed in the passage that Sinuhe has secretly received the news of death, or that he is close to the betrayal.

Scott Morschauser, however, does not see the escape as justified in fear, but thinks that Sinuhe flees with full intent, since with the death of Amenemhet he loses his protector, his home and his future at the same time. By losing the bond with his master, his secure position as the king's companion in the afterlife is also no longer applicable.

The question of the reason for Sinuhes flight seems to have already been asked by the ancient Egyptians in the New Kingdom (especially in the Ramesside period). The text of this period deviates in some places from that of the Middle Kingdom and shows traces of different levels of editing , so that the story in the New Kingdom could be read differently, or better said anew .

According to Frank Feder, some passages clearly show that Sinuhe was interpreted as the king's son of Amenemhet I in the New Kingdom. Sinuhe speaks of him in several places as "my father". The ancient Egyptian scribes may have assumed an inheritance dispute as the cause of the flight. Sinuhe could have been a son of Amenemhet I with a harem lady and had every reason to flee from his half-brother Sesostris I, who saw him as a competitor for the throne or could have linked him with the assassination attempt on Amenemhet.

Georges Posener already suspected that the rival of Sesostris on the throne could have been the son of a harem lady, a descendant of the 11th dynasty from Thebes, but without thinking of Sinuhe. Tobin took this idea further, assuming that Sinuhe could have come from a noble family under a Mentuhotep.

However, it is also pointed out that the narrative as a literary creation can create a hero who has come into this probationary situation through doubt and fear, but without guilt. So for John Baines Sinuhes reasons to flee are irrelevant with regard to the main plot. Ultimately, it's all about Sinuhe going abroad. For Vincent Arieh Tobin, the fact that Sinuhe keeps the secret of his escape to himself until the end creates an enigmatic atmosphere around this event. So the main theme of the narrative lies in this unanswered question, and the literary achievement of the author is to create a mystery that cannot be solved. He therefore suggests The Secret of Sinuhe as the title of the story .

For Garald Moers, on the other hand, Sinuhes flight is related to the breach of the cultural values of pharaonic Egypt. The point is for Sinuhe to experience himself abroad and to become aware of his identity as an Egyptian. Thus, the flight is due to the associated rejection of Egyptian lifestyles. Seen in this way, flight and guilt become a mutual condition and it is the existence of his own text that makes Sinuhe guilty. Flight and guilt thus become a mutual condition and are not driven by anything except an inner search .

Amunenschi

With the figure of Amunenschi, Prince of Oberretjenu, a foreigner is represented for the first time in Egyptian literature as a "person" with an identity of his own , in that the presentation takes place with the mention of his name and his function. Thus, he is primarily identified as a ruler and thus replaces the usual ethical generalization of the foreign as a general negative connotation . By speaking Egyptian, he is even included in the Egyptian world of meaning.

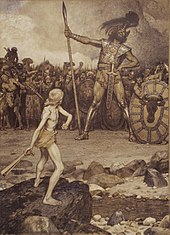

The fight against the strong of Retjenu

Sinuhes fight against the strong of Retjenu is one of the oldest descriptions of this duel, as it can be found in a similar way in the biblical story of David and Goliath ( 1 Sam 17 LUT ).

The actual course of the fight was interpreted quite differently, but it may have happened as follows: On the day of the fight, Sinuhe is already waiting for the "strong man" to demonstrate his fearlessness to him. The day before he had only prepared a bow and a dagger for the fight, weapons in which, as an Egyptian, he was certainly well trained. The "strong man" has dropped the entire arsenal of weapons that he has brought with him and is the first to fire his arrows at Sinuhe, but Sinuhe lets them fly into the void. Furious, he rushes across the battlefield to Sinuhe and is stopped by a single arrow shot. As the culmination of the abuse and culmination of Egyptian superiority - the triumph of the spirit over the raw power of the barbarian - Sinuhe kills the "strong" with his own battle ax.

There are remarkable parallels to the story of David and Goliath, which both Egyptology and Old Testament science have worked out. Both narratives show a similar course of action: challenge by the enemy fighter, advice to the hero before the fight with his superior prince, preparation for the fight, meeting of the fighters, duel and consequences of victory. Furthermore, the scene of both struggles is the Syrian-Palestinian territory and both opponents are described as invincible so far. The strong of Retjenu and Goliath are defeated with their own weapons. David defeats the Philistine in the name of God and Sinuhe defeats a traditional opponent of Egypt with the assistance of an Egyptian god ( Month ): the Asian nomads. The challenge to fight by talking and the boastful appearance before the battle seem to be characteristic of both stories. This is exactly how the heroes of the Iliad behave before their duels. Paris in the third cant, Hector in the seventh, summon the best heroes of the enemy to fight.

However, there are also significant differences between the two narratives. The most important thing is the time of origin, because Sinuhe's depiction is a good 1000 years older than the biblical tradition. Furthermore, there is no parallel portrayal of a duel in Egyptian literature and, according to Miroslav Barta, it is very likely a tradition of the Syrian-Palestinian region. Ludwig Morenz also suspects that this episode arises from Semitic coloring. In his opinion, the designation nḫt (about "strong") is probably a loan translation or paraphrase of a (West) Semitic title and the designation of the strong by Retjenu as pr.y ("outgoing", which means lone fighter ) is a kind of loan translation of a (West) Semitic terminus technicus into Egyptian . M. Görg derived the name Goliath, which is obviously a foreign word in the Old Testament, from the Egyptian word qnj ("to be strong"). If this theory is correct , there would be a particularly close connection between the “strongman of Retjenu” and Goliath because of the semantic proximity of nḫt and qnj .

Miroslav Barta also thinks it is possible that the story with the strong man was composed by Retjenu in Egypt and thus follows an Egyptian tradition, inherited from the first interim period. The story could then be in the course of the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt at the end of the 16th century BC. Passed into the Syrian-Palestinian area. Andreas Kunz also explains the similarities between the two stories by saying that the history of the reception of the Sinuhe story also left its mark in Israel / Palestine.

Parallels with the biblical story of Joseph

The biblical Joseph story , the setting of which is almost exclusively Egypt, has some similarities with the Sinuhe story , which is centuries older. Both stories address the cultural and religious identity abroad. A dark event led both of them abroad: with Josef the sale into slavery, with Sinuhe his panic-like escape. Both experience an amazing ascent abroad, Joseph as vizier, Sinuhe as confidante of a local ruler. The conciliatory conclusion is also common, so Sinuhe returns to the land of his longing and Joseph reconciles with his brothers and brings his father to Egypt. The motif of a burial in their homeland is also common, although in the Joseph story only Jacob is led in a funeral procession to the family grave in Palestine, but Joseph also ordered that an identical burial be carried out for him.

Konrad von Rabenau considers the theological approach of the stories to be even more meaningful than these similarities in details : Not only Joseph's changeful fates and actions are directed by God, Sinuhe also leads his flight, victory in a duel and the pardon by the Pharaoh to a divine one Plan back. The similarities between these culturally different narratives are astonishing, and the question arises as to whether the Joseph story was written under the impression of the Sinuhe story or whether they produced similar literary expressions independently of one another.

Modern reception

Between 1933 and 1945 Thomas Mann published the novel tetralogy Joseph and his brothers . It is the most extensive novel by this author. In it he explicitly and covertly refers to various ancient Egyptian literary works. He did not mention the Sinuhe story at any point, but alluded to it in various places. For example, he transferred the description of the paradisiacal land of Jaa partially literally to the area of Edom , in which the disinherited Esau ruled and with which he believed he had to show off to his brother Jacob .

The Finnish writer Mika Waltari used the material for his historical novel Sinuhe the Egyptians , which he published for the first time in 1945. The novel is based on extensive historical studies, but Waltari relocated the story to the 14th century BC. BC, in which Sinuhe initially worked as a doctor at the court of King Akhenaten and later made several trips to Babylon , Crete and other regions of the then known world. Based on Waltari's novel, Michael Curtiz made the film Sinuhe the Egyptians in 1954 . The name of the asteroid (4512) Sinuhe , discovered in 1939 by the Finnish astronomer Yrjö Väisälä , also refers to Mika Waltari's novel.

The Egyptian writer and Nobel Prize winner Nagib Mahfuz published a short story in 1941 entitled Awdat Sinuhi , which appeared in 2003 in English translation by Raymond Stock as "The Return of Sinuhe" in the collection of short stories entitled "Voices from the Other World". This is based directly on the ancient Egyptian Sinuhe story, but Mahfuz added various details to it that did not appear in the original, for example a triangle story .

literature

Editions

- Aylward Manley Blackman : Middle-Egyptian Stories. Part I, (= Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca . Volume 2.1). Éditions de la Fondation Égyptologique, Bruxelles 1932, pp. 1-41.

- Alan Henderson Gardiner : Notes on the story of Sinuhe. Librairie Honoré Champion, Paris 1916.

- Roland Koch: The story of Sinuhe. (= Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca . Volume 17). Éditions de la Fondation Égyptologique, Bruxelles 1990.

- Gaston Maspero : Les Mémoires de Sinouhît . (= Bibliothèque d'Étude. Volume 1). Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Le Caire 1908.

- Georg Möller: Hieratic reading pieces for academic use. First issue. Old and middle hierarchical texts. Hieratic Edition, New York 1909, pp. 6-11.

Translations

- Elke Blumenthal : Ancient Egyptian travel stories. The life story of Sinuhe. Wen-Amun's travelogue. Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1982. (2nd revised edition 1984)

- Elke Blumenthal: The story of Sinuhe. In: Otto Kaiser et al. (Ed.): Texts from the environment of the Old Testament . (TUAT), Volume III, 5: Myths and Epics. Gütersloher Verlagshaus Gerd Mohn, Gütersloh 1995, ISBN 3-579-00082-9 , pp. 884-911.

- Wolfgang Kosack : Berlin books on Egyptian literature 1 - 12. Part I. 1 - 6 / Part II. 7 - 12 (2 volumes). Parallel texts in hieroglyphics with introductions and translation. Book 1: The Story of Sinuhe. Christoph Brunner, Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-906206-11-0 .

- Miriam Lichtheim : Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volume 1: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles / London 1973, ISBN 0-520-02899-6 , pp. 222-235.

- Richard B. Parkinson: The Tale of Sinuhe and other Ancient Egyptian Poems 1940-1640 BC (= Oxford World's Classics ). Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1997, ISBN 0-19-814963-8 , pp. 21-53.

General overview

- Miroslav Bárta: Sinuhe, the Bible, and the Patriarchs. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague 2003, ISBN 80-86277-31-3 .

- Hellmut Brunner: Basic features of a history of ancient Egyptian literature. 4th, revised. and exp. Edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1986, ISBN 3-534-04100-3 .

- Günter Burkard , Heinz J. Thissen : Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. (= Introductions and source texts on Egyptology. Volume 1). 2nd Edition. Lit, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-6132-2 , pp. 114-123.

- Harold M. Hays, Frank Feder, Ludwig D. Morenz (eds.): Interpretations of Sinuhe. Inspired by Two Passages. Proceedings of a Workshop Held at Leiden University, November 27-29, 2009. (= Egyptologische Uitgaven 27) Nederlands Instituut voor het Narbije Oosten: Leiden, 2014.

- Antonio Loprieno (Ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. (= Problems of Egyptology. Volume 10). Brill, Leiden / New York / Cologne 1996, ISBN 90-04-09925-5 .

- Richard B. Parkinson : Poetry and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt. A dark side to perfection. Continuum, London / New York 2002, ISBN 0-8264-5637-5 .

- William K. Simpson: Sinuhe. In: Wolfgang Helck (Ed.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie, Volume 5. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1984, ISBN 3-447-02489-5 , pp. 950-955.

Individual questions

- Jan Assmann : The rubrics in the tradition of the Sinuhe story. In: Manfred Görg (Ed.): Fontes atque pontes (FS Brunner) (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 5). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1983, pp. 18-41. (on-line)

- John Baines: Interpreting Sinuhe. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. No. 68, 1982, pp. 31-44.

- Dylan Bickerstaffe: Why Sinuhe Ran away. In: KMT. A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt. Volume 24, No. 4, 2016, pp. 46-59.

- Martin Bommas: Sinuhes Escape. On religion and literature as a method. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. 141, pp. 15-23.

- Marcelo Campagno: Egyptian Boundaries in the Tale of Sinuhe. In: Fuzzy Boundaries: Festschrift for Antonio Loprieno. Widmaier Verlag, Hamburg 2015, pp. 335–346.

- Frank Feder: The poetic structure of the Sinuhe poetry. In: Ludwig Morenz, Stefan Schorch (Ed.): What is a text? Old Testament, Egyptological and Old Oriental Perspectives. (= Supplements to the journal for Old Testament science. No. 362). de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007.

- John L. Foster: Thought Couplets in the Tale of Sinuhe (= Munich Egyptological Studies. Volume 3). Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1993, ISBN 3-631-46005-8 .

- Kenneth A. Kitchen : Sinuhe: Scholary Method Versus Trendy Fashion. In: Bulletin of the Australian Center for Egyptology. No. 7, 1996, pp. 55-63.

- Antonio Loprieno: Topos and Mimesis. On foreigners in Egyptian literature (= Egyptological treatises. Volume 48). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1988, ISBN 3-447-02819-X .

- Gerald Moers : Fictitious worlds in Egyptian literature of the 2nd millennium BC Crossing borders, travel motifs and fictionality (= problems of Egyptology. Volume 19). Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2001, ISBN 90-04-12125-0 .

- Ludwig D. Morenz: Why does Sinuhe always stay the same? On the problem of identity and role conformity in Central Egyptian literature. In: Egyptologische Uitgaven. 27, 2014, pp. 69-80.

- Eberhard Otto : The stories of the Sinuhe and the shipwrecked as 'didactic pieces'. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. No. 93, 1966, pp. 100-111.

- Georges Posener : Littérature et politique dans l'Egypte de la XIIe dynastie. (= Bibliothèque de l'École des hautes études. Sciences historiques et philologiques. Volume 307). Paris 1956.

- Claudia Suhr: The Egyptian “first-person narration”. A narratological investigation. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2016, especially pp. 90–113.

Modern narratives

- Nagib Mahfuz : Voices from the Other World: Ancient Egyptian Tales. English translation by Raymond Stock. B & T, 2003, ISBN 977-424-758-2 .

- Elizabeth Peters : The Curse of the Hawk. Ullstein, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-548-25740-2 .

- JRR Tolkien : The Children of Húrin. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-608-93603-2 .

- Mika Waltari : Sinuhe the Egyptians. Historical novel (Original title: Sinuhe egyptiläinen. German by Charlotte Lilius ) Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2008, ISBN 978-3-404-15811-9 .

- Kathrin Brückmann : Sinuhe, son of sycamore: a novel from ancient Egypt. K. Brückmann, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-1-4904-6141-0 .

Web links

- Barbara Lüscher, Günter Lapp: Sinuhe Bibliography. (Most extensive Sinuhe bibliography, text in transcription and all text passages in the index)

- Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae (including transcription and German translation of various text witnesses)

- The Tale of Sinuhe . In: reshafim.org , (English translation)

- The life story of Sinuhe (text in hieroglyphics, transcription and German translation)

- Tale of Sanehat . In: ucl.ac.uk , (background information, text witnesses from the Petrie Museum, transcription and English translation)

- Sinuhe project In: Uni-Marburg.de , (including transcription)

- Gerald Moers: Sinuhe / Sinuhe story. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on May 26, 2012.

- Sinuhe by Mark-Jan Nederhof (transcription and English translation; PDF; 134 kB)

- David Lorton: Reading the Story of Sinuhe . (Interpretation)

- Ostracon of The Tale of Sinuhe . In: BritishMuseum.org , (text witnesses )

- Berlin Papyrus Collection, Papyrus Berlin 3022 (text witnesses)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. Berlin 2007, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: The story of Sinuhe. In: Otto Kaiser et al. (Ed.): Texts from the environment of the Old Testament III. Myths and Epics. Gütersloh 1995, p. 885.

- ^ Richard B. Parkinson: Teachings, Discourses and Tales from the Middle Kingdom. In: Stephen Quirke (Ed.): Middle Kingdom Studies. New Malden 1991, pp. 91-122, here p. 114.

- ↑ Gerald Moers: Sinuhe. In: WiBiLex .

- ↑ Roland Koch: The story of Sinuhe. Bruxelles 1990.

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath : Chronology of Pharaonic Egypt. The timing of Egyptian history from prehistoric times to 332 BC Chr. Mainz 1997, p. 189.

- ↑ a b Elke Blumenthal: The story of Sinuhe. P. 884.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: Ancient Egyptian travel stories. The life story of Sinuhe. Wen-Amun's travelogue. Leipzig 1982, p. 53 and The story of Sinuhe. P. 884.

- ↑ a b c Frank Feder: The poetic structure of the Sinuhe poetry. In: Ludwig Morenz, Stefan Schorch (Ed.): What is a text? Old Testament, Egyptological and Old Oriental Perspectives. Berlin / New York 2007, pp. 171–172.

- ↑ a b Ludwig Morenz: Canaanite local color in the Sinuhe story and the simplification of the original text. In: Journal of the German Palestine Association. (ZDPV) 113, 1997, p. 2.

- ↑ Frank Feder: The poetic structure of the Sinuhe poetry. In: Ludwig Morenz, Stefan Schorch (Ed.): What is a text? Old Testament, Egyptological and Old Oriental Perspectives. Berlin / New York 2007, p. 173.

- ↑ Frank Feder: The poetic structure of the Sinuhe poetry. In: Ludwig Morenz, Stefan Schorch (Ed.): What is a text? Old Testament, Egyptological and Old Oriental Perspectives. Berlin / New York 2007, pp. 172–174.

- ↑ Archived copy ( memento of the original dated November 23, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. with reference to: Ludwig D. Morenz: Contributions to the literacy culture in the Middle Kingdom and in the Second Intermediate Period. (= Egypt and Old Testament. (ÄAT) 29). revised dissertation. Wiesbaden 1996.

- ↑ Eberhard Otto: The stories of the Sinuhe and the shipwrecked as "didactic pieces". In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. 93, 1966, p. 111.

- ↑ Andrea McDowell: Awareness of the Past in Deir el-Medina. In: RJ Demarée, A. Egberts: Village Voices, Preceedings of the symposium "Texts from Deir el-Medina and their interpretation". Leiden 1992, p. 95.

- ^ Nicolas Grimal : La Stèle Triomphale de Pi (ankh) y au Musée du Caire. (= Mémoires publiés par les membres de l'Institut Français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. 105). 1981, p. 284.

- ↑ Frank Feder: The poetic structure of the Sinuhe poetry. In: Ludwig Morenz, Stefan Schorch (Ed.): What is a text? Old Testament, Egyptological and Old Oriental Perspectives. Berlin / New York 2007, p. 174.

- ↑ Waltraud Guglielmi: On the adaptation and function of quotations. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. 11, 1984, p. 357.

- ↑ Sinuhe R1-R10.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. Berlin 2007, pp. 117-122 and Richard B. Parkinson: The Tale of Sinuhe and other Ancient Egyptian Poems 1940-1640 BC. Oxford / New York 1997, pp. 21-25.

- ^ Sinuhe R11-B6.

- ↑ Hans Goedicke : The Route of Sinuhe's Flight. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. 43, 1957, pp. 77-85 (Route), Michael Green: The Syrian and Lebanese topographical data in the story of Sinuhe. In: Chronique d'Égypte. 58, 1983.

- ↑ Sinuhe B7-B27.

- ^ Rainer Hannig: Language of the Pharaohs. Large concise dictionary of Egyptian-German (2800-950 BC). Marburg Edition. 2009, p. 33 (m jwms: as a claim, a lie).

- ↑ Sinuhe B42.

- ↑ Sinuhe B75-77, translation: Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. Berlin 2007, p. 120.

- ↑ Sinuhe B27-B105.

- ↑ Sinuhe B106-178, quote: B158-160, translation: Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. Berlin 2007, p. 120 f.

- ↑ Sinuhe B178-B243.

- ↑ Sinuhe B254-256, translation: Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. Berlin 2007, p. 122.

- ↑ Sinuhe B244-310.

- ↑ a b Elke Blumenthal: The story of Sinuhe. In: Otto Kaiser et al. (Ed.): Wisdom texts, myths and epics. Myths and Epics III. 1995 (TUAT III, 5), 884-911, p. 885.

- ^ Gerhard Fecht: The form of ancient Egyptian literature: metrical and stylistic analysis. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. 91, 1964, pp. 11-63.

- ↑ Miriam Lichtheim: Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. Berkeley / Los Angeles / London 1973, pp. 11-12.

- ↑ John L. Foster: Thought Couplets in The Tale Of Sinuhe. (= Munich Egyptological investigations. 3). Frankfurt am Main and others 1993; Günter Burkard: Metrics, prosody and formal structure of Egyptian literary texts. In: Antonio Loprieno (ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. Leiden / New York / Cologne 1996, pp. 447-463; John L. Foster: Sinuhe: The Ancient Egyptian Genre of Narrative Verse. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies . 34, 1975, pp. 1-29.

- ↑ Translation: Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae, Sinuhe B 81-85 and AOS 36-38; Classification into Thought Couplets: John L. Foster: Thought Couplets in The Tale Of Sinuhe. (= Munich Egyptological investigations. 3). Frankfurt am Main and others 1993, p. 46.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: The rubrics in the tradition of the Sinuhe story. In: Manfred Görg (Ed.): Fontes atque pontes (FS Brunner). 1983 (ÄAT 5), pp. 18-41.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: The rubrics in the tradition of the Sinuhe story. In: Manfred Görg (Ed.): Fontes atque pontes (FS Brunner). 1983 (ÄAT 5), p. 36.

- ^ H. Ranke: The Egyptian personal names. Glückstadt 1935, p. 283, 2.

- ↑ Bill Manley: The Great Secrets of Ancient Egypt. 2007, pp. 158-161.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Scripture, death and identity. The tomb as a preschool of literature in ancient Egypt. In: Jan Assmann (Ed.): Stone and Time. Munich, 1991, p. 182.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. 2008, pp. 38-40.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. 2008, pp. 70-74; also: Jan Assmann: Scripture, death and identity. The tomb as a preschool of literature in ancient Egypt. In: Jan Assmann (Ed.): Stone and Time. Munich, 1991.

- ↑ a b Kenneth A. Kitchen: Sinuhe. Scholary Method Versus Trendy Fashion. In: Bulletin of the Australian Center for Egyptology. North Ryde, 1996, pp. 60-61.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: The story of Sinuhe. In: TUAT III, 5, p. 886.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Scripture, death and identity. The tomb as a preschool of literature in ancient Egypt. In: Jan Assmann (Ed.): Stone and Time. Munich, 1991, p. 199 ff.

- ^ Jan Assmann: Cultural and literary texts. In: Antonio Loprieno (ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. 1996, p. 60. (online)

- ^ Antonio Loprieno: Defining Egyptian Literature: Ancient Texts and Modern Theories. In: Antonio Loprieno (ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. 1996, p. 53.

- ↑ Bill Manley: The Great Secrets of Ancient Egypt. 2007, p. 161.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. 2008, p. 112.

- ↑ Michael Höveler-Müller: In the beginning there was Egypt. 2005, p. 129 ff.

- ↑ Michael Höveler-Müller: In the beginning there was Egypt. 2005, p. 149 ff.

- ↑ a b c Michael Höveler-Müller: In the beginning there was Egypt. The history of the Pharaonic high culture from the early days to the end of the New Kingdom approx. 4000-1070 BC. Chr. 2005, pp. 152-153.

- ↑ Karl Jansen-Winkeln: On the coregences of the 12th dynasty. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. 24, 1997, p. 132.

- ↑ a b c Karl Jansen-Winkeln: On the coregences of the 12th dynasty. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. 24, 1997, pp. 132f.

- ↑ Claude Obsomer: Sesostris Ier: Etude chronologique et historique du règne. 1995, pp. 130-133.

- ↑ a b Günter Burkard: "When God appeared he speaks", the teaching of Amenemhet as a posthumous legacy. In: Jan Assmann, Elke Blumenthal: Literature and Politics in Pharaonic and Ptolemaic Egypt. 1999, p. 154.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: The teaching of King Amenemhet. Part I. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. 111, 1984, p. 94.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. 2008, p. 112.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom. 2008, p. 113.

- ↑ Ludwig Morenz: Canaanite local color in the Sinuhe story and the simplification of the original text. In: ZDPV. Volume 113, 1997, pp. 2-5.

- ↑ Massimo Patanè: Quelques Remarques sur Sinouhe. In: Bulletin de la Société d'égyptologie de Genève (BSEG) 13 , 1989, p. 132.

- ↑ Albrecht Alt: Two assumptions about the history of Sinuhe. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. 58, 1923, p. 49 f.

- ↑ Manfred Bietak: Article Hyksos. In: Wolfgang Helck (Ed.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie , Volume 3, 1980, column 93.

- ↑ Ludwig Morenz: Canaanite local color in the Sinuhe story and the simplification of the original text. In: ZDPV. Volume 113, 1997, p. 3.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schenkel: Egyptian literature and Egyptological research. An introduction to the history of science. In: Antonio Loprieno (ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. 1996, p. 31.

- ^ William Kelly Simpson: Belles lettres and propaganda. In: Antonio Loprieno (ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. 1996, pp. 435-445.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. Volume I. Old and Middle Kingdom. 2008, p. 75, cited: Hannes Buchberger: Transformation und Transformat. Coffin Text Studies I. 1993.

- ^ Georges Posener: Littérature et politique dans l'Egypte de la XIIe dynastie. 1956 (= Bibliothèque de l'École pratique des hautes études, (BEHE) 307 ), p. 115.

- ^ A b John Baines: Interpreting Sinuhe. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. 68.1982, p. 31.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schenkel: Egyptian literature and Egyptological research. An introduction to the history of science. In: Antonio Loprieno (ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. 1996, p. 37.

- ↑ John Baines: Interpreting Sinuhe. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. 68, 1982, p. 44.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. I. Old and Middle Kingdom. 3. Edition. 2008, pp. 123-136.

- ^ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. I. Old and Middle Kingdom. 3. Edition. 2008, p. 135.

- ↑ Dorothea Sitzler: "Reproach against God". A religious motif in the ancient Orient (Egypt and Mesopotamia). Wiesbaden 1995, p. 230.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: The story of Sinuhe. In: TUAT III, 5th p. 886.

- ↑ Winfried Barta: The "reproach to God" in the life story of Sinuhe. In: Festschrift Jürgen von Beckerath. (= Hildesheim Egyptological contributions. 30). 1990, p. 25.

- ↑ Winfried Barta: The "reproach to God" in the life story of Sinuhe. In: Festschrift Jürgen von Beckerath. (= Hildesheim Egyptological contributions. 30). 1990, p. 26.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: The story of Sinuhe. In: TUAT III, 5. S. 886. and further: Eberhard Otto: The story of the Sinuhe and the shipwrecked as “didactic pieces”. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. 93rd volume, 1966, pp. 195ff.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Sinuhe and Wenamun - Two Egyptian hikers. In: Fritz Graf, Erick Hornung (Ed.): Walks. Eranos New Episode, p. 63.

- ^ Antonio Loprieno: Travel and Fiction in Egyptian Literature. In: David O'Connor, Stephen Quirke (Eds.): Mysterious Lands. Encounters with Ancient Egypt. 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Antonio Loprieno: Topos and Mimesis. To the foreigner in Egyptian literature. 1988, p. 10 ff.

- ↑ a b Gerald Moers: Fictionalized Worlds in Egyptian Literature of the 2nd Millennium BC Crossing borders, travel motifs and fictionality. 2001, p. 251 ff.

- ↑ Gerald Moers: Sinuhe story. In: WiBiLex .

- ^ RB Parkinson: Poetry and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt. A dark side to perfection. 2002, p. 151.

- ↑ Vilmos Wessetzky: Sinuhes Escape. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. 90, 1963, pp. 124-127, cited, p. 126; also: Richard B. Parkinson: Poetry and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt. A dark side to perfection. 2002, p. 155ff .; Hans Goedicke: The Riddle of Sinuhe's Flight. In: Revue d'Égyptologie. 35, 1984, pp. 95-103.

- ↑ Anthony Spalinger: Orientations on Sinuhe. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. 1998, p. 328.

- ↑ Frank Feder: Sinuhes father - an attempt of the New Kingdom to explain Sinuhes escape. In: Göttinger Miscellen. (GM) 195, 2003, p. 45.

- ↑ Scott Morschauser: What Made Sinuhe Run: Sinuhe's Reasoned Flight. In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 37. 2000, p. 198.

- ↑ Frank Feder: Sinuhes father - an attempt of the New Kingdom to explain Sinuhes escape. In: Göttinger Miszellen 195. 2003, p. 45 and p. 47.

- ↑ Pen: Sinuhes father. In: GM 195. pp. 48-51.

- ↑ Pen: Sinuhes father. In: GM 195. P. 52 with reference to: G. Posener: Littérature et Politique dans l'Égypte de la XIIe Dynastie. 1956, p. 85.

- ↑ Pen: Sinuhes father. In: GM 195. p. 52 with reference to: VA Tobin: The Secret of Sinuhe. In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt No. 32, 1995, p. 165 and p. 171.

- ↑ Pen: Sinuhes father. In: GM 195. p. 46.

- ↑ John Baines: Interpreting Sinuhe. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology 68, 1982, pp. 39-42.

- ↑ Vincent Arieh Tobin: The Secret of Sinuhe. In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt No. 32, 1995, pp. 177-178.

- ↑ Gerald Moers: Fictitious worlds in the Egyptian literature of the 2nd millennium BC. Chr. 2001, pp. 253-254.

- ^ Antonio Loprieno: Topos and Mimesis. To the foreigner in Egyptian literature. 1988, p. 41ff.

- ↑ Peter Behrens: Sinuhe B 134 ff or the psychology of a duel. In: Göttinger Miszellen 44. 1981.

- ↑ Günter Lanczkowski: The story of the giant Goliath and the battle of Sinuhes with the strongman of Retenu. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department (MDIK) 16. 1958, pp. 214–218.

- ↑ Miroslav Barta: Sinuhe, the Bible, and the Patriarchs. 2003, p. 49ff.

- ↑ Günter Lanczkowski: The story of the giant Goliath and the battle of Sinuhes with the strongman of Retenu. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department (MDIK) 16. 1958, pp. 214–215, with quotation from: Felix Stähelin : Die Philister. Basel, 1918, p. 27.

- ↑ Miroslav Barta: Sinuhe, The Bible and the Patriarchs. 2003, pp. 51-52.

- ↑ Ludwig Morenz: Canaanite local color in the Sinuhe story and the simplification of the original text. In: ZDPV. Volume 113, 1997, pp. 10f.

- ↑ Ludwig Morenz: Canaanite local color in the Sinuhe story and the simplification of the original text. In: ZDPV. Volume 113, 1997, p. 10 with reference to: M. Görg: Goliat from Gat. In: Biblical Notes. 34, 1986, pp. 17-21.

- ↑ Miroslav Barta: Sinuhe, the Bible, and the Patriarchs. 2003, p. 55.

- ↑ Andreas Kunz: Sinuhe and the strong one by Retjenu - David and the giant Goliat. A sketch on the use of motifs in the literature of Egypt and Israel. In: Biblical Notes. 119/120, 2003, p. 100.

- ↑ Konrad von Rabenau: Inducio in tentationem - Joseph in Egypt. In: E. Staehelin, B. Jaeger (ed.): Egypt pictures. (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. 150). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Friborg / Göttingen 1997, pp. 35–49, p. 47.

- ↑ Konrad von Rabenau: Inducio in tentationem - Joseph in Egypt. In: E. Staehelin, B. Jaeger (ed.): Egypt pictures. (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. 150). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Friborg / Göttingen 1997, pp. 35-49, pp. 47-48.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: Thomas Manns Joseph and the Egyptian literature. In: E. Staehelin, B. Jaeger (ed.): Egypt pictures. (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. 150). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Friborg / Göttingen 1997, pp. 223-225.

- ^ Nagib Mahfuz: Voices from the Other World: Ancient Egyptian Tales. 2003 (in English translation by Raymond Stock).