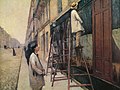

The parquet sander

First version of the painting by

Gustave Caillebotte , 1875

102 × 146.5 cm

oil on canvas

Musée d'Orsay , Paris

The parquet grinder , also known as the parquet scraper or the parquet slicer ( French Les raboteurs de parquet ), are a repeatedly depicted motif in the oeuvre of the French painter Gustave Caillebotte . In addition to two painting versions, he created a preparatory oil study and numerous drawings on paper. The pictures show craftsmen whoare busyworking on the parquet floor in a Parisian apartment. The first painting version of the parquet grinder ,created in 1875,is 102 × 146.5 cm, painted in oil on canvas and belongs to the collection of the Musée d'Orsay in Paris . This picture was one of the artist's first works in a public collection and is one of his most famous works. Caillebotte varied the subject in a second version of the painting in 1876. This painting, which is in a private collection, is also painted in oil on canvas and with dimensions of 80 × 100 cm is significantly smaller than the first version. Such representations of workers are in the tradition of the works of French realism and have their model, for example, in the works of Gustave Courbet . The contemporary critics discussed the paintings controversially and partly rejected the motif of the work, others praised the talent of the young painter.

Image motif and image title

Caillebotte found the motif for the depiction of the parquet workers in his parents' apartment at 77 Rue Miromesnil in Paris. It is known from surviving documents that renovation work was carried out there from late 1874 to May 1875. The house in which his family lived from 1868 was built as part of the modernization of Paris undertaken by Prefect Georges-Eugène Haussmann and was only a few years old when Caillebotte documented the work of the craftsmen with pictures. The title The Parquet Grinder is misleading for the work shown, as none of the people shown is actually involved in sanding the parquet. According to research by the art historian Kirk Varnedoe , Caillebotte does not show workers sanding off an old layer of wax, but rather while repairing defects in a relatively new floor. Varnedoe suspects that the planks may have kinked upwards a little along the edges, i.e. what is known as bowls . The dark, glossy parquet areas shown in Caillebotte's paintings were accordingly soaked on the surface with water in order to prevent the wood from splintering during further processing. The light stripes in the parquet show the edges that have already been processed, the light surface an area that has already been closed. The work itself is in this case the one with a planer (French rabot ) and another with a scraper (French racloir running). Correspondingly, the image titles Die Parettabzieher and Die Parettthobler are derived from this.

Preparatory drawings

First, Caillebotte made a series of drawings that document the different work processes and show the men in different postures. As a close observer, he sketched the craftsmen using their tools with pencil on paper. He depicts her in typical kneeling postures while pulling the parquet or shows her in a sitting position while sharpening the blades. There are also detailed drawings of the hands or a balcony railing. He probably drew these sketches on site in the rooms in which the craftsmen worked. The paintings, on the other hand, were created later in his attic studio.

Oil sketch for the first version of the painting

Grinder Oil study for the first painting version

Gustave Caillebotte , 1875

26 × 39 cm

oil on canvas

Private collection

In preparation for the large-format first version of the painting, Caillebotte first made a small oil sketch. The essential scheme of the later composition is already present in this first study. Apart from the fleeting brushstroke, the room in the sketch differs from the following representation in the first version of the painting, especially in the shape of the window grille and the wall paneling. While in the study the balcony grille still shows more floral motifs, the later painting version mainly shows arched forms. In the preliminary study, the paneling next to the window is a large field framed several times, while rows of smaller cassettes characterize the wall design in the painting version. Since the view from the window also shows a different picture of the opposite houses, it is possible that the preliminary study describes a different room than the later painting version. The art historian Anne Distel suspected that the room of the preliminary study was possibly on a different floor than the room of the first painting version. In the three crafts in the room, the middle and right figures appear almost identical in the later version of the painting. In contrast, the craftsman on the left is shown in the preliminary study in a completely different position than in the final version. In the preliminary study, he kneels with an upright back and holds both hands in front of him. In the painting version he can be seen turned to the side with his upper body stretched out and a hand reaching to the floor.

First painting version

The painting shows an interior with three craftsmen. The view falls from above on the men busy working on a wooden floor. The room has been cleared for work and there is no furniture in it. The floor, with its wooden floorboards running towards the rear, takes up a large area in the room view; the lower area of the walls or a window can be seen at the top and right of the picture. The art historian Kirk Varnedoe sees "a tilting floor that seems threateningly unreal" in the room, which is widened to the rear with a high horizon line . The walls are clad with panels in which gold-plated decorative strips stand out from the white background. In addition to the surrounding strips, the wall is divided into cassette-like fields. The horizontal lines of the wall panels and the vertical lines of the wooden floor create a spatial effect characterized by geometric components. This contrasts with the arched ornamentation of the window grille. Behind it, the outside world appears in the form of opposite house roofs and a light gray sky. A diffuse light falls into the room through the closed window that extends to the floor.

The three parquet workers are arranged side by side in the painting. They wear long, dark work trousers and their torsos are bare. The central figure in the center of the picture and the man to the right of him appear in a similar posture. Both are positioned frontal to the viewer while kneeling and bending their upper bodies forward. With outstretched arms they work on the parquet with tools. The man on the right is holding a plane with both hands, which he uses to work the uneven edges of the boards. The man in the center of the picture is shown with a scraper in the following operation. The third worker, moved further back on the left edge, can be seen at an angle from the side. While supporting himself with his left hand, he grabs a knife-like tool on the floor with his right hand in front of him. This could, for example, remove loose nails in the parquet. Another tool that protrudes from the lower edge of the picture is a file that was used to sharpen the tools. There is also a hammer between the men on the right side. In the back corner there is a sack that the craftsmen used to transport their utensils. On top of and next to it are knee pads that are not needed. On the right side, a dark bottle and a filled glass can be seen on a light background. It remains open whether it is red wine for the craftsmen or whether there is a dark liquid to treat the wood. The floor was partially moistened and shines accordingly. In addition to these dark areas, there are light areas that have already been treated by the workers. In addition, the wood chips scattered on the floor testify to the work process. The signature “G. Caillebotte 1875 ”is on the parquet in the lower right corner.

When you sweat from working on the parquet, the men's bare backs in particular appear shiny. Although the men are used to hard work, their bodies appear not very muscular and their arms are unnaturally elongated. All three craftsmen are absorbed in their work. Even if the craftsman on the right and the man in the middle seem to have their heads bowed, it is not clear whether they are communicating with each other or whether they just happen to adopt this head position. Their faces are barely recognizable and their physiognomy appears similar. Kirk Varnedoe therefore saw the possibility that the same man can be seen three times in the painting, each doing different work steps. Similarly, Claude Monet had already depicted his lover Camille Doncieux three times in the painting Women in the Garden in 1866 . The art historian Karin Sagner wrote about this, Caillebotte shows in the picture of the parquet sander "different phases of work and different attitudes among men, who are hardly differentiated by appearance". He emphasizes "the repetitive character of their work".

Second version of the painting

Second version of the painting by

Gustave Caillebotte , 1876

102 × 146.5 cm

oil on canvas

Private collection

The second painting variant was created by Caillebotte a year after the first painting version. It is not a repetition of the previous composition, but a new execution while maintaining the theme. Caillebotte first applied this practice to the motif of the parquet sander; This way of working is repeated in his later works.

In the second version of the painting, Caillebotte also used his fund of preparatory drawings. This time two craftsmen can be seen in one room, although the room bears little resemblance to the grand ambience of the first variant. The view does not go head-on to the outer wall with the window, but rather stripes diagonally across the room towards a corner where a side wall from the right meets the outer wall protruding into the picture from the left. Instead of a panel, the wall decoration is limited to a two-tone coat of paint with a contrasting border. A surrounding red line separates the red-brown base area from the upper white part of the wall. In the upper left corner there is a window that has been cropped from the edges of the picture and reaches close to the floor. In front of the closed window there is a balcony grille made of straight vertical struts, which is closed at the top by a band with circular openings. These strict geometric shapes in the window lack the playfulness that can be found in the first version of the painting. Through the window you can see the facade of a house opposite.

The two craftsmen are arranged diagonally behind one another in the room. They differ in posture, clothing and appearance. The age difference between the men is clearly visible. The front worker already has a bald spot in the dark hair. He is shown in a side view kneeling with his torso bent forward while he works the wooden floorboards with a plane. He is dressed in dark trousers and a light shirt or undershirt. His left knee protector can also be seen. Next to it is a knife with a wooden handle that is currently not needed. His young colleague sits in the back corner with his legs stretched out and his torso straight. He wears light gray trousers and brown leather knee pads over them. The upper body is naked and rather slim. He holds his hands in front of his chest and is busy cleaning or sharpening a tool. His individual facial features differ significantly from the rather shadowy depiction of the other workers.

The workers in this room are not as advanced with their work as in the first version of the painting. The floor shines from the treatment with a liquid, the reflection of the window can be seen on the left edge. So far, only a few narrow strips of the removed parquet can be seen. Accordingly, there are only a few wood chips and no finished surface. The art historian Anne Distel emphasized that in this version the light shines brighter into the room and that it appears cooler overall than in the previous version. The painting is signed 'G. Caillebotte 1876 “signed and dated.

Motives of the work - models and contemporary representations

Born into a wealthy family, Gustave Caillebotte studied painting from 1871 with the academic artists Léon Bonnat , Alexandre Cabanel , Jean-Léon Gérôme , Adolphe Yvon and Isidore Pils . Afterwards he oriented himself in his early works on the traditional style of the École des Beaux-Arts . One of these early works is the picture studio interior with oven from 1873–1874 (private collection), which shows his studio in the attic of his parents' house at 77 rue Miromesnil. In this painting works of art are contained as room decorations, which give the first clues as to which models Caillebotte's work was based on. In the studio painting on the left wall there are two Japanese pictures in landscape format, whose typical perspective with sloping lines Caillebotte adopted in many of his works. This influence of Japanese art on the composition can also be felt in the motifs of the parquet sander . The plaster copy of a male nude statue by Jean-Antoine Houdon on the chest of drawers also refers to the painter's classical training, which also included anatomy studies. This knowledge later helped Caillebotte to visualize the parquet workers with their bare torsos. However, he did not create idealized bodies here, as they were handed down from antiquity and can be found in the mythological pictures of the academic painters of his time. Instead, Caillebotte painted men with bare chests of the present as a description of everyday life. The author Kirk Varnedoe suspected that Caillebotte used the subject of the half-bared parquet workers as a pretext to capture the naked torso of the men in the picture. Even before Caillebotte, the painter Frédéric Bazille had tried his hand at the contemporary portrayal of the shirtless when he portrayed young men doing sporting activities on a river in the painting Bathers (Summer Scene) from 1869 ( Fogg Art Museum , Cambridge (Massachusetts)).

Caillebotte's teacher, Bonnat, gave the advice to his students that they should paint the truth rather than depict beauty. In his parquet sanders, Caillebotte created a “ naturalistic ” motif, but at the same time remained “quite academic” in his painting style, as the art historian Claude Keisch noted. Correspondingly, Caillebotte was able to find a number of motivic models among the artists of realism , who devoted themselves in different ways to the representation of workers. Examples of this are the works of Jean-François Millet , in which he captured the working life of the rural population. These include the painting Women Gatherers from 1857 (Musée d'Orsay, Paris) or other motifs with brushwood collectors , forest workers, shepherds or field workers. Another well-known working-class motif of French realism was shown by Gustave Courbet in his painting Die Steinklopfer from 1849 ( Galerie Neue Meister , Dresden, loss of war), in which he portrayed two men in ragged clothes doing heavy physical activity.

While the artists of realism depicted the workers predominantly in rural surroundings, the painters of impressionism saw in the urban workers a motif worthy of picture and showed them as part of modern life. In 1875, the same year Caillebotte created the first version of the parquet grinder , Claude Monet painted his picture of the coal carriers (Musée d'Orsay). Here he shows in a sketchy version the hustle and bustle on the banks of the Seine in the Paris suburb of Asnières . The workers appear in the painting as dark figures who balance over boards and bring coal from the ships to shore. Monet is not portrayed herein individual worker, but represents the process of working as part of a Cityscape represents. Quite different was Edgar Degas before that in 1876 in the second group exhibition of the Impressionists at the side of Caillebotte's parquet grinders a painting entitled Blanchisseuse (silhouette) exhibited . This was probably the painting The Ironer from 1873 ( Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York City), showing a single worker in an interior. The living conditions of urban workers were also repeatedly addressed in contemporary literature. In his first work Marthe , published in 1876, Joris-Karl Huysmans describes the social decline of a factory worker and Émile Zola describes the fate of a washerwoman in his 1877 novel Der Totschläger . While Huysmans and Zola in their novels, like Degas in his pictures, primarily dealt with the women of the working class, Caillebotte was until then the only one “who showed male workers in such a monumental way”. Caillebotte took up the worker theme again in 1877 and created the painting The Facade Painter . and Die Gärtner (both private collections). Then he devoted himself to other topics.

The parquet grinder in the mirror of contemporary criticism

Caillebotte was one of the younger painters in the Impressionist circle. For example, Claude Monet and Edgar Degas were eight years older than Caillebotte and had started painting more than a decade before him. Caillebotte first attempted his exhibition debut in 1875 in the Salon de Paris , but the jury responsible for the admission rejected his painting. Art historians like Anne Distel assume that this work was the first painting version of the parquet grinder. The author Gry Hedin suspected that the rejection of the parquet grinder was less due to the painting style, as Caillebotte was still oriented towards academic painting. The jury's reason for rejection was rather the motif of the picture, "because the representation of modern workers in large format was considered inappropriate and unacceptable".

Edgar Degas probably convinced Caillebotte to take part in the second group exhibition of the Impressionists in 1876. Caillebotte thus publicly demonstrated that he belonged to this group of painters. In the exhibition, which took place in the rooms of the gallery owner Paul Durand-Ruel in the Rue Peletier in Paris, Caillebotte showed, among other works, the two painting versions of the parquet sanders .

In connection with the exhibition in 1876, critics judged the parquet sanders from negative to mocking, but sometimes there were also words of praise. Louis Énault, for example, wrote about Caillebotte in Le Constitutionnel magazine, saying that although he knows his trade and has a command of perspective, the subject of the parquet workers is undoubtedly vulgar. In the first version of the painting, he criticized the craftsmen's arms, which he thought were too thin, and the unsuccessful upper bodies from his point of view. The critic Emile Porcheron judged the exhibition in the newspaper Le Soleil critically, but found Caillebotte "the least bad" ( les moins mauvaises ). He insinuated that the seated worker, who was sharpening the blade of his tool in the second picture, was looking for fleas. However, it was precisely this seated figure that was praised by the critic Bertall . In his article in the newspaper Le Soir , he also attested that Caillebotte had talent. Philippe Burty expressed himself in a similarly positive way in the newspaper La République française , who certified that the beginner Caillebotte had a sensational start. Even Armand Silvestre praised Caillebotte. In L'Opinion nationale he described him as a good observer in the succession of Courbet. The writer Emile Zola found words of praise for Caillebotte's work, but criticized the too detailed execution of his paintings.

Provenances of the group of works

Caillebotte and some of his painter friends initiated the Vente des impressionnistes on May 28, 1877 at the Hôtel Drouot auction house . The two painting versions of the parquet sanders were also offered at this auction . With little interest in buying and low prices, the first painting version of the parquet grinder achieved the highest price in the auction at 655 francs, but the buyer was Gustave Caillebotte himself, who secured the picture for himself. The painting remained in the artist's possession until his death in 1894. In his will he had decreed that his collection of paintings and works by his artist friends should go to the French state. He had not planned any of his own pictures as a gift. In the negotiations for the acceptance of the inheritance, his brother Martial Caillebotte and the painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir , who was appointed executor, managed to get two works by Caillebotte to go to the French state. The two paintings were the wintry cityscape of snow-covered roofs and the first painting version of the parquet sander . The pictures were exhibited in the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris from 1896 . These were the first works by Caillebotte to be found in a museum collection. The parquet sanders came to the Louvre in 1929, and from 1947 they could be seen in the Galerie du Jeu de Paume . The first painting version of the parquet grinder has been part of the collection of the Musée d'Orsay since 1986 .

The second version of the painting was acquired by the artist's family at auction in 1877 at the Hôtel Drouot auction house for an unspecified price. It eventually came into the possession of Eugène Daufresne, a cousin of Caillebotte's mother who lived in Paris. The relative owned a number of paintings by Caillebotte, which he bequeathed to Martial Caillebotte, the painter's brother, after his death in 1896. The picture was never on the art market and is in French private ownership. Furthermore, the oil study for the first painting version and all preparatory drawings came into the family of Martial Caillebotte by inheritance. Most of them are still privately owned. This does not include the drawings Study of a Seated Man, Front View and Three Studies of the Parquet Workers: Two Studies of the Hands, Study of a Kneeling Man from the Front , which belong to the collection of the Musée Camille Pissarro in Pontoise .

literature

- Marie Berhaut : Gustave Caillebotte, catalog raisonné des peintures et pastels. Wildenstein Institute, Paris 1994, ISBN 2-908063-09-3 .

- Norma Broude: Gustave Caillebotte and the fashioning of identity in impressionist Paris. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick 2002, ISBN 0-8135-3018-0 .

- Anne Distel u. a .: Gustave Caillebotte, Urban Impressionist. Exhibition catalog Paris, Chicago and Los Angeles. Abbeville Press Publishers, New York 1995, ISBN 0-86559-139-3 .

- Anne Distel: Gustave Caillebotte: The unknown impressionist. Exhibition catalog Royal Academy of Arts in London. Ludion Press, Gent 1996, OCLC 34974238 .

- Anne-Brigitte Fonsmark, Dorothee Hansen , Gry Hedin: Across the water - Gustave Caillebotte. An impressionist rediscovered. Exhibition catalog Kunsthalle Bremen, Ordrupgaard in Charlottenlund and Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. Hantje Cantz, Ostfildern 2008, ISBN 978-3-7757-2190-5 .

- Ernst-Gerhard Güse : The discovery of light, landscape painting in France from 1830 to 1886. Saarland Museum, Saarbrücken 2001, ISBN 3-932036-11-5 .

- Claude Keisch et al. (Ed.): From Courbet to Cézanne. French painting 1848–1886. Exhibition catalog. Nationalgalerie, Berlin 1982, DNB 830938044 .

- Serge Lemoine : Dans l'intimité des frères Caillebotte, peintre et photographe. Catalog for the exhibition at the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris and the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec. Flammarion, Paris 2011, ISBN 978-2-08-125706-1 .

- Charles S. Moffett : The new painting, impressionism 1874–1886. National Gallery of Art, Washington and Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Phaidon, Oxford 1986, ISBN 0-7148-2430-5 .

- Mary G. Morton, George ™ Shackelford, Michael Marrinan: Gustave Caillebotte, the painter's eye. Exhibition catalog National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC and Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2015, ISBN 978-0-226-26355-7 .

- Karin Sagner : Gustave Caillebotte, New Perspectives on Impressionism. Hirmer, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-7774-2161-2 .

- Karin Sagner: Gustave Caillebotte, New Perspectives on Impressionism. Hirmer, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-7774-5411-5 .

- Kirk Varnedoe : Gustave Caillebotte. Yale University Press, New Haven 1987, ISBN 0-300-03722-8 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Die Parettschleifer gives the Musée d'Orsay on its website as a German title. The title can also be found in Karin Sagner's two publications: Gustave Caillebotte. New perspectives on impressionism. 2009, p. 76 and Gustave Caillebotte. An Impressionist and Photography , 2012, p. 77; in Ernst-Gerhard Güse: The Discovery of Light, landscape painting in France from 1830 to 1886 , p. 174 and in Rudolf Leopold: Impressionists from the Paris Musée d'Orsay. Leopold Museum, Vienna 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ The painting versions are titled as Die Parettabzieher in Anne-Brigitte Fonsmark, Dorothee Hansen, Gry Hedin: About the water - Gustave Caillebotte. 2008, pp. 50-53. The picture was also shown under this title in 1982 in the exhibition From Courbet to Cézanne - French Painting 1848–1886 in the Berlin National Gallery, see exhibition catalog, p. 109.

- ↑ The painting version of the Paris Musée is titled Parquet Slicer in Théodore Duret: The Impressionists: Pissarro, Claude Monet, Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Cézanne, Guillaumin . B. Cassirer, Berlin 1914, p. 33; in Michael Bockemühl: image reception as image production, selected writings on image theory, art perception and economic culture . Transcript, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-8376-3656-7 , p. 198; in Gottfried Boehm, Karlheinz Stierle: Modernity and Tradition . Fink, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-7705-2318-0 , p. 33; Narnara Paul: Hugo von Tschudi and modern French art in the German Empire . Von Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1416-7 , p. 464; Both painting versions are entitled Parquet Hobler in Klaus Türk: Images of Work, an iconographic anthology. Westdeutscher Verlag, Wiesbaden 2000, ISBN 3-531-13358-6 , p. 176.

- ↑ Les raboteurs de parquet is the title that Marie Berhaut used in the 1994 catalog raisonné (pp. 74-77) and this is the name under which the Musée d'Orsay exhibits its version of the painting.

- ↑ In Marie Berhaut's catalog raisonné from 1994 the paintings bear the numbers 34 and 35. It is also noted that Claude Renoir is said to have owned another version of the painting in 1943, as his brother Pierre Renoir later recalled. Pierre Renoir was a godchild of Gustave Caillebotte, his father Pierre-Auguste Renoir was his executor. There is no further information on appearance and size about this picture. The work, which has only been handed down orally, has not received its own catalog number in the catalog raisonné. See Marie Berhaut: Caillebotte, catalog raisonné. 1994, p. 75.

- ^ Karin Sagner: Gustave Caillebotte, New Perspectives of Impressionism. 2009, p. 76.

- ↑ Anne Distel: The parquet puller. In: Claude Keisch et al. (Ed.): From Courbet to Cézanne - French painting 1848–1886. 1982, p. 109.

- ↑ Michael Marrinan: Caillebotte's Deep Focus. In: Mary G. Morton, George TM Shackelford, Michael Marrinan: Gustave Caillebotte, the painter's eye. 2015, p. 26.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 54.

- ↑ Detailed information on the drawings can be found in Anne Distel, among others: Gustave Caillebotte, Urban Impressionist. 1995, pp. 42-51 and in Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, pp. 54-58.

- ^ A b Anne Distel and others: Gustave Caillebotte, Urban Impressionist. 1995, p. 40.

- ^ Karin Sagner: Gustave Caillebotte, New Perspectives of Impressionism. 2009, p. 76.

- ^ "The tipped-up floor seemed threateningly unreal" in Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 54.

- ↑ a b Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 55.

- ^ Karin Sagner: Gustave Caillebotte, New Perspectives of Impressionism. 2009, p. 77.

- ^ A b c Anne Distel and others: Gustave Caillebotte, Urban Impressionist. 1995, p. 42.

- ^ Marie Berhaut: Gustave Caillebotte, catalog raisonné des peintures et pastels. 1994, p. 77.

- ^ Serge Lemoine: Dans l'intimité des frères Caillebotte, peintre et photographe. 2011, p. 21.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Gry Hedin: Arbeiterbilder - The figure in focus. In: Anne-Brigitte Fonsmark, Dorothee Hansen, Gry Hedin: Across the water - Gustave Caillebotte, An impressionist rediscovered. 2008, p. 50.

- ↑ Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 50.

- ^ "The subject may have been partly a pretext for showing the nude torsos ..." In: Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 54.

- ↑ Bonnat's advice to his students is passed down through a statement by the Danish painter Laurits Tuxen . See Anne Distel: Gustave Caillebotte: The unknown impressionist. 1996, p. 39.

- ↑ Claude Keisch et al. (Ed.): From Courbet to Cézanne. French painting 1848–1886. 1982, p. 109.

- ^ Anne Distel: Gustave Caillebotte: The unknown impressionist. 1996, p. 40.

- ↑ Information on the painting The Ironing Woman (English title A Woman Ironing ) on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ For the painting Die Fassadenmaler see for example Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, pp. 84-87.

- ↑ For the painting Die Gärtner see Anne Distel et al .: Gustave Caillebotte, Urban Impressionist. 1995, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ See Marie Berhaut: Gustave Caillebotte, catalog raisonné des peintures et pastels . 1994.

- ↑ The critic Emile Blémont noted in the newspaper Le Rappel on April 9, 1876 that a painting by Caillebotte had been rejected by the salon the previous year. See Anne Distel and others: Gustave Caillebotte, Urban Impressionist. 1995, p. 31.

- ^ Anne Distel and others: Gustave Caillebotte, Urban Impressionist. 1995, p. 31.

- ^ Anne Distel: Gustave Caillebotte: The unknown impressionist. 1996, p. 39.

- ^ "Le sujet est vulgaire sans doute". Louis Énault: Mouvement Artistique - L'Éxposition des Intransigeants dans la Galerie de Durand-Ruelle [sic!] In Le Constitutionnel of April 10, 1876 (digitized) , reproduced in Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 186.

- ↑ Louis Renault: - Mouvement Artistique l'Exposition of Intransigeants dans la Galerie de Durand-Ruelle [sic] in Le Constitutionnel from April 10, 1876 (digitized) , are listed in Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 186.

- ↑ Emile Porcheron: Promenades d'un flâneur - Les Impressionistes in Le Soleil of 4 April 1876 reproduced in Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 185.

- ↑ Bertall: exposure of Impressionistes, Rue Lepeletier in Le Soir , April 1876, are listed in Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 187.

- ^ Philippe Burty: Chronique du jour in La République française of April 16, 1876, reproduced in Charles S. Moffett: The new painting, impressionism 1874-1886. 1986, p. 167.

- ^ Philippe Burty: L'Opinion nationale in La République française of April 16, 1876, reproduced in Charles S. Moffett: The new painting, impressionism 1874-1886. 1986, p. 167.

- ↑ Emile Zola's review appeared as Lettre de Paris, deux éxpositions d'art in Russian translation in the June 1876 issue of the St. Peterburg magazine Westnik Jewropy , reproduced in Kirk Varnedoe: Gustave Caillebotte. 1987, p. 187.

- ^ Marie Berhaut: Gustave Caillebotte, catalog raisonné des peintures et pastels. 1994, p. 75.

- ^ Marie Berhaut: Gustave Caillebotte, catalog raisonné des peintures et pastels. 1994, p. 77.

- ^ Marie Berhaut: Gustave Caillebotte, catalog raisonné des peintures et pastels. 1994, p. 74.

- ^ Anne Distel and others: Gustave Caillebotte, Urban Impressionist. 1995, pp. 48-49.