Task Force Process

The task force process was the ninth of twelve Nuremberg follow-up processes . It was carried out from September 15, 1947 to April 10, 1948 in jury court room 600 of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice , in which the Nuremberg trial of major war criminals before the International Military Tribunal (IMT) had already taken place. In contrast to the main war criminals trial, the Einsatzgruppen trial took place before an American military tribunal (NMT); there was no four-power control . The case was officially referred to as “The United States of America against Otto Ohlendorf, et al. "(German:" The United States of America against Otto Ohlendorf and others ").

The accused were 24 former SS leaders who, as commanders of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD, were responsible for the crimes of the Einsatzgruppen in the occupied Soviet Union . Before the war against the Soviet Union began, the Einsatzgruppen were given the task of murdering Soviet functionaries and the “ Jewish intelligentsia ” of the Soviet Union. During the first three months of the war against the Soviet Union, the murderous activity of the Einsatzgruppen escalated in the east, so that by the beginning of October 1941 at the latest, Jewish men, women, children and old people were shot without distinction. Dispatched prisoners of war , " gypsies ", psychiatric patients and hostages from the civilian population were among the victims of the task forces. The number of victims who were murdered by the Einsatzgruppen from June 1941 to 1943 in the Soviet Union is estimated at at least 600,000, according to other sources at more than a million people. The indictment went out on the basis of the task force reports from more than one million victims.

The trial ended without acquittal: 14 defendants were sentenced to death , two received life sentences, and five were sentenced to between ten and twenty years' imprisonment. A defendant committed before the trial suicide , a pull out due to illness from the process and another was after adding the were serving remand dismissed. In the course of integration into the West, High Commissioner John McCloy converted ten of the 14 death sentences against those detained in the Einsatzgruppen Trial in Landsberg to imprisonment on the recommendation of the Advisory Board on Clemency for War Criminals . Four of them were commuted to life sentences and six sentences were reduced to ten and twenty-five years respectively. Four death sentences were carried out on June 7, 1951. The sentences of other inmates have also been reduced. The last three prisoners in the Einsatzgruppen trial were released in May 1958.

History and preparation of the procedure

Task Force Groups in the War against the Soviet Union (1941–1943)

Task forces to “clean up the liberated areas from Marxist traitors and other enemies of the state” were used for the first time during the “ Anschluss of Austria ” to the German Reich . The first Einsatzgruppe, the Einsatzkommando Österreich, was under the orders of Franz Six , a later defendant in the Einsatzgruppen trial. Also with the annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938 and with the " smashing of the rest of the Czech Republic " in 1939, task forces or task forces were used to track down and destroy opponents of National Socialist rule. While the Einsatzgruppen operated on these missions before the outbreak of the Second World War on the basis of lists of named opponents, the raid on Poland took on genocidal features for the first time . Certain groups, such as members of the Polish intelligentsia, Catholic priests and nobles, were declared enemies and in many cases murdered. Although the number of victims and the number of Einsatzgruppe members involved in Poland was considerable, these murders played no role in the Einsatzgruppen process. Based on the evidence, the prosecution concentrated on the actions of the Einsatzgruppen in the occupied Soviet Union , beginning with the preparation for the attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 up to the incorporation into stationary units or the beginning of the withdrawal in 1943.

As early as March 13, 1941, about three months before the attack by the German Reich on the Soviet Union, the head of the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA), Reinhard Heydrich , informed the quartermaster general of the Wehrmacht, Eduard Wagner, about the use of task forces in the course of the "Operation Barbarossa". Hitler himself had previously entrusted Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler with the implementation of the "special measures" during Operation Barbarossa:

“In the area of operations of the army, the Reichsführer SS is given special tasks on behalf of the Führer in preparation for the political administration, which result from the final battle between two opposing systems. In the context of these tasks, the Reichsführer SS acts independently and on his own responsibility. [...] The Reichsführer SS ensures that operations are not disrupted while carrying out his duties. The OKH regulates further details directly with the Reichsführer SS. "

Heydrich, as Himmler's deputy, and the commander-in-chief of OKH Walther von Brauchitsch finally determined the following after negotiations: The Wehrmacht should provide logistical support to the Einsatzgruppen, and the Einsatzgruppen should take responsibility for special security tasks in the rear army area . These tasks should include securing important documents of anti-state organizations, arresting important individuals, and investigating "anti-state activities".

About 3,000 suitable members of the RSHA and the Waffen SS were recruited for the Einsatzgruppen and gathered in Pretzsch , Saxony, in May 1941 . At this point in time, there was no general "order to kill Jews", but the issuing of orders gradually developed. In June / July 1941, the task of the Einsatzgruppen was to murder the “ Jewish-Bolshevik intelligentsia” and resistance fighters in the occupied territories and to support the local population in anti-Jewish pogroms . Only in August / September 1941 was a general "order to kill Jews" issued to the leaders of the Einsatzgruppen. A total of four task forces were formed, which in turn were divided into task forces or special commands:

- The Einsatzgruppe A , first under the commander of Walter Stahlecker , belonged to about 1,000 men. Starting from East Prussia, their area of operations was the rear army area of Army Group North in the Baltic States and the adjacent north-eastern Russian districts as far as Leningrad .

- The Einsatzgruppe B , initially under Commander Arthur Nebe , consisted of about 655 men. Starting from Warsaw, their area of operations was the rear army area of Army Group Center from Belarus to the edge of Moscow .

- The Einsatzgruppe C , first under the Commander Otto Rasch , belonged to about 700 men. Starting from Upper Silesia, their area of operations was the rear army area of Army Group South in central Ukraine .

- The Einsatzgruppe D , initially under the command of Otto Ohlendorf , consisted of around 600 men. Their area of operation was the rear army area of the German 11th Army and the Romanian Army in Moldova , southern Ukraine and the Crimea .

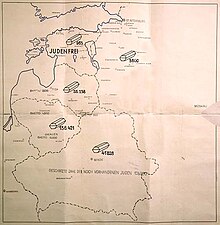

On June 23, 1941, one day after the attack on the Soviet Union, the Wehrmacht Einsatzgruppen followed suit. The commandos of the Einsatzgruppen carried out massacres of local Jews, "Gypsies", prisoners of war and communist functionaries, sometimes with members of the local police and in the presence or even with the help of the population. The victims, including women, children and old people, were mainly murdered in groups by shooting in ravines, pits or quarries. The mass shootings led many members of the task force to psychological exceptional symptoms, which did not disappear due to the considerable alcohol consumption that was tolerated. For this reason, the RSHA also provided the task forces with so-called gas vans in which the mostly Jewish victims were murdered using exhaust gases from the end of 1941. The massacre in the Babi Yar gorge , which killed more than 33,000 Jews on September 29 and 30, 1941 , gained particular fame . At the turn of the year 1941/42, the Einsatzgruppen reported the following figures on the Jews killed: Einsatzgruppe A 249,420, Einsatzgruppe B 45,467, Einsatzgruppe C 95,000, Einsatzgruppe D 92,000. A member of the Wehrmacht witnessed shootings and reported after the end of the war:

“Among other things, there was an old man with a full white beard in the grave who had a small walking stick hanging over his left arm. Since this man was still giving signs of life through his intermittent breathing, I asked one of the policemen to kill him for good, whereupon he said with a laughing face: 'I've already put something in his stomach seven times, he'll die on his own.' "

After the establishment of a German civil administration in the occupied Soviet territories , further mass murders of Jews were committed by units of the Ordnungspolizei, Waffen-SS and so-called local volunteers who were subordinate to the higher SS and police leaders. In total, at least 600,000 and possibly over 1,000,000 people fell victim to these murders. The special commandos of Aktion 1005 , headed by Paul Blobel, had to exhume the buried bodies of the murdered from summer 1943 and then burn them in order to remove the traces of these crimes.

Otto Ohlendorf as a witness (1945–1946)

Otto Ohlendorf , as SS-Brigadefuhrer and commander of Einsatzgruppe D, was one of the three highest-ranking defendants in the Einsatzgruppen trial. Only Jost and Naumann were equal to him in rank and position, but Ohlendorf was also far superior to these two co-defendants in terms of intellect, demeanor and charisma. For example, Ohlendorf would be at the center of the proceedings on the part of the defendants, whose official name corresponds to The United States of America against Otto Ohlendorf, et al. read. Before even the preliminary consideration of an Einsatzgruppen trial took place, Ohlendorf gave testimony about the structure, orders and operations of the Einsatzgruppen: first as a prisoner of war for the British and then as a witness for the indictment in the Nuremberg trial of major war criminals . Without Ohlendorf's statements, the task force process would probably not have taken place, as they gave the impetus to expand and focus the follow-up process. The American prosecutor Whitney Harris said of Ohlendorf that he “created the Einsatzgruppen process”.

In July 1942, Ohlendorf had given command of Einsatzgruppe D to Walther Bierkamp and had returned to the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin , where he again took over the management of SD-Inland (Office III). He also worked for the Reich Ministry of Economics . At the end of the war, Ohlendorf stayed with the Dönitz government near Flensburg . On May 21, 1945, Ohlendorf and hundreds of Dönitz government employees were taken prisoner by the British because he hoped that he would also be useful to the Allies as a “pollster” and self-declared economic expert.

Ohlendorf's statement in Nuremberg was a sensation. On January 3, 1946, he took the witness stand for the first time and shocked the defendants and their defense lawyers with the soberly presented details of the Einsatzgruppen mass murders. His testimony was extremely valuable for the prosecution: The second IMT prosecutor Telford Taylor described Ohlendorf's testimony as “real blockbuster” in the sense of the burden of proof in his memoirs (roughly: the statement “hit like a bomb”). Ohlendorf was questioned on the witness stand by the prosecution, John Amen , who had already conducted his interrogation in British captivity in 1945 and in some cases personally conducted it. Under Amen's questioning, there was a decisive breakthrough in Ohlendorf's expressive behavior. Other members of the military tribunal later claimed that the decisive Ohlendorff confession had been obtained, according to Judge Musmanno in his book about the trial. Musmanno gives the impression that he “single-handedly investigated, indicted, negotiated and convicted”.

Find of the Einsatzgruppen reports in Berlin (1946–1947)

The task force reports were of central importance for the task force process - for its establishment, for the identification and search for the suspects and as evidence in the process itself. The term "task force reports" refers to the following series of reports and documents:

- USSR event reports , 195 of which occurred between June 1941 and April 1942. Except for one report, all of them were retained.

- Activity and situation reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD in the USSR , which were submitted in the same period as the USSR incident reports , but at longer intervals. These reports are of a more general nature and often deal with the same acts as the incident reports.

- Reports from the occupied eastern territories , which replaced the USSR event reports as regular reports. Compared to the USSR event reports, these reports contain less direct statements about the murder of the Jews, but more details about the fight against partisans.

- Three reports: two reports by Walter Stahlecker , the first from October 1941 and the second from January 1942, as well as the Jäger report by Karl Jäger from December 1941.

These reports were reported to the RSHA in the period from June 1941 to May 1943 by the staff of the Einsatzgruppen by radio and courier in Berlin . They contained detailed information on the numbers of murdered Jews and other Soviet citizens, on crime scenes and the units involved. The reports were kept confidential; most of them were marked “ Secret Reichssache .” Two-digit numbers were copied and then numbered copies were passed on. The distribution included recipients in offices of the RSHA as well as in high offices in the NSDAP, Reich government and the military. Even in the Einsatzgruppen, the number of people with access to these reports and their transmission was limited, so in Einsatzgruppe D only three officers and one radio operator had access to their own reports.

The American unit 6889th BDC ( Berlin Document Center ) secured files from the Reich and Nazi authorities in Berlin from 1945 onwards on the orders of General Lucius D. Clay . The main task was to provide the four-power administration with the necessary administrative documents. The focus on the documentation and prosecution of Nazi crimes only developed gradually with the submission of administrative documents to bizonal and then German authorities. The 6889th BDC thus formed the origin of the Berlin Document Center . On September 3, 1945, the 6889th BDC seized two tons of documents on the fourth floor of the Gestapo headquarters on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse in Berlin (today the Topography of Terror ). The documents contained, among other things, 578 files from the holdings of the RSHA and the Gestapo. Twelve of the files (No. E316 and E325 – E335) contained an almost complete set of the incident reports from the USSR and the reports from the occupied eastern territories . From then on, the Einsatzgruppen reports were in the possession of the Americans, but they weren't discovered until a year later: at the end of 1945 , according to estimates, more than 1,600 tons of documents were in various locations of the Document Center units in the American zone From Ferencz, the Berlin BDC alone had eight to nine million seized documents in custody. The review of the files was slow. Therefore, the Einsatzgruppen reports of the prosecution in the Nuremberg Trial of Major War Criminals were not yet known and there was no evidence there.

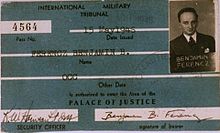

Brigadier General Telford Taylor headed the investigations in the Nuremberg follow-up trials as chief prosecutor - first as Robert H. Jackson's deputy and then from October 1946 as his successor . In early 1946, Taylor was in Washington, DC to recruit staff for the investigative agency he headed, the Office of Chief of Counsel for War Crimes (OCCWC), which turned out to be difficult: the few lawyers who served the US Army Had gained experience in investigating and prosecuting war crimes in 1944/45, they were now demobilized and unwilling to give up a lucrative occupation in civilian life at home in order to wear a uniform in destroyed Germany. As a result, the OCCWC was chronically understaffed. The criminal law professor Sheldon Glueck , with whom Taylor had studied at the Harvard Law School (HLS), recommended the young HLS graduate Benjamin Ferencz to him as a "promising student", who had experience investigating war crimes at the Judge Advocate in Germany from February 1945 had collected. Ferencz was demobilized at the end of 1945 and is returning to the USA. On March 20, 1946, Ferencz accepted Taylor's offer and was now a civilian crimes investigator at the OCCWC. Ferencz was just 26 years old. He returned to Germany in mid-1946. Taylor immediately sent him to Berlin , where Ferencz was to build a team of investigators. His task included checking the documents confiscated by the National Socialist authorities with regard to their usability for the Nuremberg follow-up trials. On August 16, 1946, Taylor appointed Ferencz head of the Berlin branch of the OCCWC.

Ferencz dates the discovery of the Einsatzgruppen reports to the end of 1946 / beginning of 1947. An employee of his OCCWC team showed him several Leitz files, which contained a numbered set of the mimeographed original reports. Ferencz immediately recognized the importance of the reports as evidence, flew to Nuremberg and presented them to Taylor. The first written mention of the Einsatzgruppen reports in OCCWC documents comes from January 15, 1947. From March to April 1947, the Ferencz team analyzed the Einsatzgruppen reports. When comparing the identified perpetrators with the personnel records of the prisoners of war in American hands, it turned out that some of those now wanted had already been released as "unencumbered", including Heinz Schubert . Time was of the essence - in retrospect, analysis and criminal exploitation of the task force reports by the Americans were only possible within a narrow time frame. At the beginning of 1947 Taylor was planning 18 follow-up trials in Nuremberg, but had to reduce this volume in view of a lack of budget and time. On March 14, 1947, Taylor proposed to the American military government that three of the planned processes should not be carried out as "less necessary". One of the trials to be curtailed was planned against Ohlendorf and other high-ranking members of the SD, the Gestapo and the RSHA. Up to this point in time the gravity of the Einsatzgruppen crimes and the evidential value of the Einsatzgruppen reports had not yet been recognized by the top of the American prosecution.

Decision for the trial and establishment of the court (1947–1948)

When Ferencz first presented the task force reports to his superior Taylor in early 1947, he initially refused to initiate an additional task force process. There simply isn't enough staff, budget, and time to carry out more than the follow-up processes that have already been planned. What exactly caused Taylor to change his mind remains unclear, it may have been the urgency of Ferencz's lecture or the clear evidence based on the Einsatzgruppen reports - in any case Taylor converted the proceedings planned against Ohlendorf and a loosely defined group of high-ranking SS offenders : The proceedings should now only concern the Einsatzgruppen in the occupied Soviet Union, only Ohlendorf should remain the accused. On March 22, 1947, Taylor appointed the lead prosecutor for the trial: Benjamin Ferencz , at the age of 27 the youngest lead prosecutor in the Nuremberg Trials. That was the formal hour of birth of the Einsatzgruppen process.

Ferencz later wrote that Taylor gave him "his" trial on one condition: no recruitment of prosecutors or investigators to the OCCWC; the process had to take place within the (personnel) budget and time frame that had already been set. Ferencz succeeded in removing four public prosecutors from the subsequent Nuremberg trials , which were running in parallel : Arnost Horlik-Hochwald, originally from the Czech Republic , Peter Walton from Georgia , John Glancy from New York and James Heath from Virginia . These employees did not make up the elite of the US military attorney's office; the other senior prosecutors tended to give up their worse employees. James Heath in particular, while a seasoned prosecutor, had a serious drinking problem . Taylor originally wanted to fire Heath, but Ferencz, who had shared a room with Heath in Nuremberg, gave him a chance.

The competent court was the Nuremberg Military Tribunal II (NMT-II). The presiding judge was Michael A. Musmanno , previously a judge in Pittsburgh , Pennsylvania . John J. Speight , a distinguished Alabama attorney , and Richard D. Dixon , a former North Carolina State Supreme Court judge , completed the bench. The process was dominated by Musmanno.

The defendants

Among the accused were eight lawyers, a university professor, a dentist, an opera singer and an art expert. In order of their rank, six brigade leaders (equivalent to the generals of the Wehrmacht), 16 Sturmbann, Obersturmbann and Standartenführer (staff officers from major to colonel) and one Oberscharführer (NCO) were charged. The accused Haussmann committed before the opening of proceedings on 31 July 1947 in the custody of suicide . The indictment was completed on July 3, 1947 and supplemented on July 29, 1947 with the names of other accused, namely Steimle, Braune, Haensch, Strauch, Klingelhöfer and Radetzky. The indictment submitted to the court was handed over to the accused in July 1947 and contained the following three charges relating to all of the accused:

- Crimes against humanity

- War crimes

- Membership in a criminal organization

Illustrations of the defendants

- Photos of the originally 24 defendants on admission to custody

2. Heinz Jost

4. Erwin Schulz

5. Franz Six

6. Paul Blobel

7. Walter Blume

10. Eugen Steimle

11. Ernst Biberstein

12. Werner Braune

13. Walter Haensch

14. Gustav Nosske

15. Adolf Ott

16. Eduard Strauch

18. Lothar Fendler

20. Felix Rühl

21. Heinz Schubert

22. Matthias Graf

23. Otto Rasch

24. Emil Haussmann

List of defendants

| No. | Dgr. | Surname | function | EG | Year | NSDAP since | SS since | SD since | Sentence 1948 | Served sentence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SS crypt. | Ohlendorf | Commander of Einsatzgruppe D (1941–1942) | D. | 1907 | 1925 | 1926 | 1936 | death penalty | Executed in 1951 |

| 2 | SS-Brif. | Jost | Commander of Einsatzgruppe A (1942) | A. | 1904 | 1928 | 1934 | 1934 | Lifelong | Dismissed in 1952 |

| 3 | SS-Brif. | Naumann | Commander of Einsatzgruppe B (1941–1943) | B. | 1905 | 1929 | 1935 | 1935 | death penalty | Executed in 1951 |

| 4th | SS-Brif. | Schulz | Leader of the Einsatzkommando 5 (1941) | C. | 1900 | 1933 | 1935 | 1935 | 20 years imprisonment | Dismissed in 1954 |

| 5 | SS-Brif. | Six | Leader of the Sonderkommando 7c (1941) | B. | 1909 | 1930 | 1935 | 1935 | 20 years imprisonment | Dismissed in 1952 |

| 6th | SS-Staf. | Blobel | Leader of the Sonderkommando 4a (1941–1942) | C. | 1894 | 1931 | 1931 | 1935 | death penalty | Executed in 1951 |

| 7th | SS-Staf. | flower | Leader of the Sonderkommando 7a (1941) | B. | 1906 | 1933 | 1935 | 1935 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1955 |

| 8th | SS-Staf. | Sandberger | Leader of Sonderkommando 1a (1941–1943) | A. | 1911 | 1931 | 1935 | 1935 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1958 |

| 9 | SS-Staf. | Seibert | Head of Office III / Deputy Head of Task Force D (1941–1942) | D. | 1908 | 1933 | 1935 | 1936 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1954 |

| 10 | SS-Staf. | Steimle | Leader of Sonderkommandos 7a / 4a (1941 / 1942–1943) | B. | 1909 | 1932 | 1936 | 1936 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1954 |

| 11 | SS-Staf. | Biberstein | Leader of the Einsatzkommando 6 (1942–1943) | C. | 1899 | 1926 | 1936 | 1940 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1958 |

| 12 | SS-Ostbf. | Tan | Leader of the Sonderkommando 11b (1941–1942) | D. | 1909 | 1931 | 1934 | 1934 | death penalty | Executed in 1951 |

| 13 | SS-Ostbf. | Haensch | Leader of the Sonderkommando 4b (1942) | C. | 1904 | 1931 | 1935 | 1935 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1955 |

| 14th | SS-Ostbf. | Nosske | Leader of the Einsatzkommando 12 (1941–1942) | D. | 1902 | 1933 | 1936 | 1936 | Lifelong | Dismissed in 1951 |

| 15th | SS-Ostbf. | Ott | Leader of the Sonderkommando 7b (1942–1943) | B. | 1904 | 1922 | 1931 | 1934 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1958 |

| 16 | SS-Ostbf. | shrub | Leader of the Einsatz- / Sonderkommandos 2 / 1b (1941 / 1941–1943) | A. | 1906 | 1931 | 1931 | 1934 | death penalty | ./. A. |

| 17th | SS-Stbf. | Klingelhöfer | Leader of the Sonderkommando 7c (1941) | B. | 1900 | 1930 | 1933 | 1934 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1956 |

| 18th | SS-Stbf. | Fendler | Head of Office III in Sonderkommando 4b (1941) | C. | 1913 | 1937 | 1933 | 1939 | 10 years imprisonment | Dismissed in 1951 |

| 19th | SS-Stbf. | from Radetzky | Officer in Sonderkommando 4a (1941–1942) | C. | 1910 | 1940 | 1939 | No | 20 years imprisonment | Dismissed in 1951 |

| 20th | SS-Hstf. | Rühl | Officer in the Sonderkommando 10b (1941) | D. | 1910 | 1930 | 1932 | 1935 | 10 years imprisonment | Dismissed in 1951 |

| 21st | SS-Ostf. | Schubert | Adjutant to Otto Ohlendorf (1941–1942) | D. | 1914 | 1934 | 1934 | 1934 | death penalty | Dismissed in 1951 |

| 22nd | SS-Osha. | Count | Sergeant in the task force 6 | C. | 1903 | 1933 | 1933 B | 1940 | Time of detention | Released in 1948 |

| 23 | SS-Brif. | Quickly | Commander of Einsatzgruppe C (1941) | C. | 1891 | 1931 | 1933 | 1933 | No judgement. C. | ./. |

| 24 | SS-Stbf. | Haussmann | Officer in the task force 12 | D. | 1910 | 1930 | k. A. | 1937 | No judgement. D. | ./. |

All information in the table of the accused except for information on Haussmann after Earl: The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial .

A Strauch was extradited to Belgium, where he was sentenced to death again. The judgment was not carried out for health reasons, and Strauch died in 1955.

B Graf joined the SS in 1933, but was excluded again in 1936 due to a lack of participation. In 1940 he rejoined the SS as part of his service for the SD.

C Rasch left the proceedings due to illness on February 5, 1948, and died on November 1, 1948.

D Hausmann committed in 1947 in custody on July 31 suicide and longer belonged to from the process.

defense

Like the eleven other Nuremberg follow- up trials, the Einsatzgruppen process took place on the basis of Control Council Act No. 10 (CCL10). CCL10 adopts the provisions of the London Statute , including its procedural rules. These rules of procedure gave each defendant the right to counsel of his choice. A defendant who chose a lawyer or this could not pay, was a public defender asked. In practice, the defendants chose their own defense counsel. If the desired lawyer accepted the mandate, his work was remunerated by the American military government at RM 3,500 per month, and an additional RM 1,750 when taking on a further mandate in the same process. The fringe benefits were significantly more valuable than the salary: every lawyer received three meals a day in the American canteen with an energy content of 3,900 kcal , while the German population in the American zone officially consumed a maximum of 1,500 kcal / day per person during the famine winter of 1947/48 Received food cards . In addition, the lawyers received a carton of cigarettes a week, the real hard currency until the currency reform of June 1948. The black market price of a carton of cigarettes in the winter of 47/48 was between 1,000 and 2,000 RM. The appointment as a criminal defense attorney in the Nuremberg Trials was popular among attorneys, and most of the defendants were defended by their attorneys of choice.

Although the main hearing was conducted simultaneously in German and English using simultaneous interpreters , lawyers with a knowledge of both languages had an advantage. The minutes were only kept in English and published in an abbreviated form: lawyers with English language skills were able to correct some translation errors in the minutes before they were included in the official proceedings (German: "minutes of meetings"). Almost every defendant had two defense attorneys , a main defense attorney and his assistant. More than 40 lawyers were involved in the proceedings on the defense side. In terms of numbers, the prosecution's defense was 2: 1 superior. However, this superiority was more than outweighed by the large investigative team of the public prosecutor's office (an “ army of researchers ”). In addition, the defense was also disadvantaged by the short preparation time compared to the public prosecutor's office and the lack of familiarity with the customs of a procedure that at least culturally took place according to American legal understanding. In order to compensate for these structural disadvantages and not to give the appearance of an unfair trial, the American military government provided the defense lawyers with the infrastructure to carry out their tasks: The defense lawyers had the right to stand in the Defendant's Information Center Inspection of all procedural files, and there witnesses could be summoned and questioned by the defense. The defenders were also able to use heated office space here for the duration of the proceedings, an important detail in war-torn Nuremberg.

Selection of defense lawyers

The defendants were hardly restricted in their choice of lawyers. While language and procedural knowledge would have spoken for an American lawyer, such lawyers were hardly available in Nuremberg in 1947. It also seemed fairer to the Americans to allow German lawyers to act as defense attorneys, who, in addition to language and culture, shared with the defendant the common experience of the Nazi era . All defense lawyers were German. Political burdens before 1945 were also no obstacles to admission to the procedure. In the interests of avoiding unfair restrictions, only attorneys who had been classified as “main culprits” in their arbitration panel proceedings were excluded . So was Hans Gawlik before 1945 in Breslau as a prosecutor working, sometimes even on a special court , was a defender of Naumann but admitted.

Some of the more than 40 lawyers involved also acted as defense lawyers in other Nazi trials : Rudolf Aschenauer , defender of Ohlendorf, represented several hundred defendants in Nazi trials in the course of his legal career and was also a right-wing extremist publicist and co-founder of numerous organizations, the defendants assisted in Nazi trials or carried out press and lobby work on their behalf. Hans Gawlik was appointed head of the state central legal protection office in 1950 and, together with his assistant Gerhard Klinnert, who was Seibert's main defender, also represented the concentration camp doctor Waldemar Hoven in the Nuremberg medical trial . Günther Lummert , defender of Blume, also worked as a criminal defense lawyer in the IG Farben trial and in the Wilhelmstrasse trial , after which he worked as a lawyer at the Cologne Higher Regional Court and published for the conservative Markus Verlag on international law and peace research. Lummert had been a lawyer at the Wroclaw Higher Regional Court since 1930 . The respected Nuremberg lawyer Friedrich Bergold , defender of Biberstein, represented Martin Bormann in absentia in the Nuremberg trial . Fritz Riediger, defender of Haensch, also represented Walter Schellenberg in the Wilhelmstrasse trial. Most of these lawyers were already admitted to the bar at the time of National Socialism , so Hans Surholt , defender of Rasch, was admitted as a criminal defense attorney before the People's Court .

Defense arguments

There was no coordinated strategy among the 22 defense teams. This was primarily a consequence of the different evidence and contributions of the individual defendants. A line of defense that emphasized the injustice of the actions of the task force and the repentance of the defendant, but at the same time sought to minimize the individual contribution to the crime and, if possible, emphasized an inner distance from the Nazi regime, was promising for defendants like Graf and Rühl . With men like Ohlendorf and Blobel , it would have been doomed to fail. The short preparation time and lack of experience with the modalities of legal proceedings according to American customs also played a role. The overwhelming evidence, which was based solely on the activity reports of the task forces and the interrogation protocols of the defendants themselves, remained decisive. Accordingly, the various legal teams put forward a different mix of more or less weak defense arguments in the hope of getting a hit with at least one of the arguments after the shotgun method. As a result, they undermined each other's positions.

Despite all the differences in the pleadings, the defense lawyers had three "lines of defense":

- denying the criminality of the accused's actions in the Einsatzgruppen,

- the minimization of the individual contribution of a defendant,

- the submission of mitigating circumstances in favor of the accused.

A questioning of the legality of the indictment in the Einsatzgruppen trial on the basis of the principle nulla poena sine lege was difficult in the case of organized mass murders at the middle command level - in contrast to the Nuremberg trial of major war criminals, where a new offense had been created with " Crimes against Peace ". Questions of the legality and jurisdiction of the court were clarified by CCL10 and were not addressed in the proceedings.

The criminality of the acts was contested with two main arguments: the killing of the victims of the task forces was a putative defense , and the respective accused acted under a state of emergency .

Almost every criminal defense lawyer tried to present the individual contribution of his client as low as possible. At the simplest level, it was about the times of presence at the crime scenes of the mass shootings, for example whether a defendant had actually started his post as commander of a special squad on the 15th of the month or not until two months later. Evidence of visits to the dentist in Berlin and the like were submitted for calendar reconstruction. The question of the presence in the East at certain times was crucial because the prosecution brought forward a number of concrete allegations for each defendant with locations and calendar dates from the task force reports. Although isolated charges were dismissed, most of the accused were charged with responsibility for a whole series of mass murders. Absence during one of the mass murders did not absolve from guilt for the remaining acts. A more serious argument was the lack of command . With clearly identified unit leaders of the Einsatzgruppen, special commandos and Einsatzkommandos, this defense was hopeless, unlike with staff officers like Seibert , Fendler or Radetzky . The defense lawyers of such defendants regularly submitted that their clients - as in the case of Seibert and Fendler, who were Heads of Office III (Defense and Intelligence) - were only concerned with gathering information. Radetzky's lawyer tried to portray his work, which included translation, as a pure specialty without decision-making power. Occasionally it was alleged that the defendants were not only innocent in the murders, but had not even noticed them and had not even known them from hearsay. The latter allegation, however, questioned the credibility of a defendant rather than distancing him from the deeds of his unit as desired.

The defense lawyers brought mitigating circumstances for each of the accused. Witnesses and affidavits should testify to the good repute and strength of character of the accused, which is customary in American law as character evidence . Subordinate and assured SD and SS men verbally and in writing that the accused was a caring superior and an upright officer. Only Blobel , who was considered “vicious and cowardly”, was the only accused among his peers to be so despised that he could not make any such statements in his favor. Another common argument was human behavior in other missions outside of the Einsatzgruppen. During his time as KdS in Norway in 1945, Braune was downright opposition because he had repealed orders from Reich Commissioner Terboven and released the interned Einar Gerhardsen . The points put forward as mitigating circumstances weakened other arguments in part and were thus counterproductive in terms of the defense. Several defendants alleged that, out of “care for their husbands”, any subordinate who drank too much or otherwise failed to cope with the “executions” had been transferred back to Berlin. This nullified the argument that there was a need for orders for each subordinate. The positive behavior in other service missions without loss of career, disciplinary measures, even the death penalty showed that a decision against the killing was possible.

Procedure and judgment

The Defendant's Plea (September 1947)

On September 15, 1947, the proceedings were opened by reading out the indictment in the presence of the defendants. This procedural step is part of the Anglo-Saxon criminal procedural law as an arraignment . The defendant must respond to the reading of the indictment ( plea ) and plead either "guilty" or "not guilty". All of the defendants in the Einsatzgruppen trial responded with “Not guilty as charged”. The meaning of this answer was not questioned, but it became clear in the course of the trial: In view of the burden of proof, the defense could not contest the involvement of the defendants and therefore tried to refute the individual guilt of the defendants by means of a mistake in permissions and a lack of orders. The reply “not guilty as charged” became the standard answer in war crimes trials in the years to come, also because the defense attorneys from the Nuremberg trials developed into specialists in this field and coordinated.

Main hearing (September 1947 to February 1948)

The main hearing in the Einsatzgruppen trial began on September 29, 1947 in front of the Military Tribunal II-A in jury court room 600 of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice , where the main war criminals trial had taken place two years earlier . The chief prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz opened the main hearing by presenting the indictment. Despite the importance of the trial and the six-digit number of murder victims, the prosecution only took two days to present their evidence. 253 pieces of evidence were put forward, which consisted almost exclusively of excerpts from the "activity and situation reports" of the task forces as well as affidavits by the defendants. The unusually short time of two days for the taking of evidence was explained by both the strength of the evidence and the difficulty of summoning witnesses for the prosecution from Stalin's Soviet Union or even carrying out on-site investigations. Therefore, the prosecution presented only two witnesses, Rolf Wartenberg, an interrogator at OCCWC and François Bayle from the French Navy, as a handwriting expert occurred.

On October 6, 1947, Rudolf Aschenauer, the first defense attorney , pleaded . His client was Ohlendorf . Aschenauer was one of the youngest attorneys in the trial, but quickly took on a leadership role on the defense side, as did his client among the defendants. Aschenauer made a dramatic appearance, to Judge Musmanno he looked like a "Shakespeare actor". To the surprise of the court, Aschenauer denied neither the act nor Ohlendorf's involvement. His client was involved in executions in the occupied Soviet Union. However, these executions should be seen as state self-defense - at least that is what his client believed at the time of the crime. Therefore, there is a case of putative self-defense . The putativnotwehr existed in the German legal system as well as in the Anglo-American legal system, where it was used - albeit rarely - in the case law . The accused had innocent civilians shot, but did so in the belief that he had to do it to protect the German Reich from Bolshevism (read: "the Jews") and the continued existence of the German people in the "agony with the Soviet Union ”. Aschenauer's second line of defense was the command emergency . Ohlendorf was under military command, and through a direct chain of command from Hitler via Bruno Linienbach , the “Führer order” gave him the order to exterminate the Jews. Failure to comply would have had dire consequences for Ohlendorf - in the war, failure to obey orders was punishable by death.

The main hearing lasted until February 1948 and took 78 days. From February 4 to 12, 1948, the defense lawyers pleaded. On February 13, 1948, the prosecution's closing argument took place.

Sentence and verdict (March to April 1948)

In discussing the verdict after the trial was over, the three judges Musmanno, Speight and Dixon quickly realized that they would impose death sentences under the law. Musmanno had already worked as a judge on death sentences in the Pohl trial , but not as a senior judge. He now bore heavily on his responsibilities, having worked against the death penalty in the past, trying to stop the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti , and serving as a defense lawyer and auditor in Pennsylvania. Musmanno told Ferencz in a letter after the verdict was announced that he found the death penalty to be an “unbearable burden” on his conscience. Musmanno spent sleepless nights thinking of looking someone in the face and telling them that they were about to die. Musmanno, of Italian-American descent and Catholic, asked an old friend, US Army Chaplain Francis Konieczny, for spiritual assistance.

Towards the end of March, the judges had completed the work of reaching a verdict. Konieczny helped Musmanno at his request to find a place of retreat to “meditate and pray”. This place was a monastery 50 km from Nuremberg , where Musmanno spent a few weeks. He was supported by the monks Stephan Geyer from the Seligenporten monastery and Carol Mesch. In addition to his mother tongue, Mesch also spoke Italian and translated for Geyer, who only spoke German. Musmanno also invited Lieutenant Giuseppe Ercolano, whom he knew from his time in the war in Italy . The content of the talks has not been recorded, but there is a significant indication of how Musmanno was able to reconcile the death penalty with his conscience: every accused sentenced to death had himself admitted murder during the trial. Defendants who denied everything despite the overwhelming burden of proof were not given the death penalty. In this sense, Musmanno remained true to his approach to the death penalty: where there was a risk of a miscarriage of justice , he rejected it as irrevocable, but when there was a confession and a major guilt he considered it the correct punishment.

From April 8 to 9, 1948, the court pronounced the verdicts in the Einsatzgruppen trial. All of the accused were found guilty. Except for the accused Rühl and Graf, who were only accused of membership in a criminal organization, the other accused had also been convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity . The sentence was set on April 10, 1948. There were 14 death sentences: Ohlendorf had already admitted the murder of 90,000 people as a witness in the main war criminals trial. Blobel thought the number of Babyn Yar victims (33,000) was excessive, but he admitted 10,000 to 15,000 victims. Blume and Sandberger admitted the murder of people, even if they pleaded an emergency. Braune admitted the Simferopol massacre . Haensch admitted to having ordered and directed mass shootings, even if he had forgotten the exact number. Naumann still considered the “Führer order” to be correct and acted accordingly, even if the number of victims of 135,000 seemed “a bit exaggerated” to him. Biberstein attended executions to gain the experience. Schubert admitted that he directed the execution of 800 people. As Ohlendorf's deputy, Seibert was complicit in his murders. Strauch admitted to having carried out the order. Klingelhöfer hoped for Hitler's victory and had carried out the order. Also Ott and Steimle received the death penalty. Defendants who did not admit murder ( Fendler , Nosske , Radetzky , Rühl , Schulz and Six ) were sentenced to long prison terms. Even Jost , with the SS general rank and commander of Einsatzgruppe A, was not sentenced to death because he had not admitted his actions. Graf was the only defendant who left the courtroom as a free man; his sentence was compensated for with the length of his pre- trial detention .

Execution of judgments

After the verdict was pronounced, the convicts of the Einsatzgruppen trial were also transferred to the Landsberg War Crimes Prison to serve their sentences, with the exception of Graf, whose prison sentence had already been settled through pre- trial detention. Those sentenced to death had to wear red jackets and were therefore commonly referred to as "red jackets" . The prisoners could take part in cultural events and organize them themselves. Many of the prisoners imprisoned in Landsberg rejoined the church during their imprisonment, including Blobel and Klingelhöfer. With the exception of Nosske, all those convicted of the Einsatzgruppen trial submitted appeals for clemency , which, however, were refused by the American military governor Lucius D. Clay in March 1949. Meanwhile, there was criticism of the American War Crimes Program in the German public , especially from the church and the political side. In the course of collective repression, campaigns for the prisoners in Landsberg began in the late 1940s. The prisoners were portrayed as victims who had acted under an emergency, slandered by vengeful witnesses and convicted on dubious legal grounds. The judgments themselves were defamed as “ winning justice ”. The protests were originally related to the review of the Dachau Malmedy Trial , which ended on July 18, 1946. In this trial, all 73 defendants were found guilty of the shooting of American prisoners of war during the Battle of the Bulge . A total of 43 death sentences were pronounced. The lawyers for those convicted of the Malmedy Trial publicly accused the American interrogators of using torture to obtain confessions from the accused. The US Army therefore started internal investigations which did not reveal any evidence of systematic mistreatment of the accused. In addition, a fair negotiation was certified. Nevertheless, the protest found support not only from the prisoners, their families and lawyers, but also from representatives of the Catholic and Protestant Church, the press and public institutions. In addition, this criticism gradually expanded to the other proceedings of the Dachau and Nuremberg follow-up trials. The supporter propaganda now called for a review of all the proceedings of the Nuremberg and Dachau trials and, as a result, the suspension of the death penalty and a reduction in prison sentences. These demands were underpinned by the reference to an imperative to order, non-constitutional interrogation methods, questionable legal bases, unequal sentencing for identical offenses and later also the abolition of the death penalty. Instead of the term “war criminal”, the term “prisoner of war” or “war convict” was often used from the beginning of the 1950s for those imprisoned in Landsberg. In the press and in politics, the term so-called war criminals gradually gained acceptance instead of the term war criminal or was only put in quotation marks. Ultimately, war criminals were often no longer referred to as such.

As representatives of the Catholic Church, the Cologne Cardinal Josef Frings and the auxiliary bishop in the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising Johannes Neuhäusler , who had been imprisoned as a special prisoner in the Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps , were particularly active. Neuhäusler and Frings intervened vehemently in favor of the Landsberg inmates with American politicians and congressmen and also obtained a positive statement from the Vatican . Neuhäusler also got involved with Blobel.

Theophil Wurm , regional bishop of the Evangelical Church in Württemberg , was at the forefront of the commitment of representatives of the Evangelical Church for the Landsberg prisoners. Together with Neuhäusler he founded the “Christian Prisoners Aid ” in 1949, which from October 1951 as an association for silent help for prisoners of war and internees did further support and lobbying work. In March 1949, Wurm's legal advisor described the crimes of the Einsatzgruppen as “the heaviest burden on the German name in the world for decades” and advised against any further engagement in favor of the “Ohlendorf Group”. Nevertheless, Wurm also stood up for those convicted of the Einsatzgruppen trial. Another prominent Protestant advocate of the "war convicts" was Otto Dibelius .

Further lobbying in favor of those imprisoned in Landsberg was carried out by the Heidelberg Juristenkreis , of which Rudolf Aschenauer was a central figure in the protest . In addition to lawyers, judges and officials from the Ministry of Justice, this association also included administrative experts from the Protestant and Catholic Churches.

The German population largely rejected the American War Crimes Program . So it is not surprising that German politicians also intervened in favor of the Landsberg prisoners at the relevant American authorities. After the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany in May 1949, Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer also appealed to McCloy at the end of February 1950 to suspend executions and convert the sentences to prison terms after the abolition of the death penalty, which is anchored in the constitution . In the German Bundestag, all parties represented there, with the exception of MPs from the KPD and a few SPD MPs, took this position. In particular, representatives of the FDP campaigned for those imprisoned in Landsberg. For example, Federal President Theodor Heuss and Carlo Schmid were committed to Sandberger . Even in the USA, where the majority support for the Nuremberg Trials, right-wing conservative and anti-communist politicians initiated campaigns in favor of those imprisoned in Landsberg. As opponents of the Truman government, the American Senators William Langer ( North Dakota ) and Joseph McCarthy ( Wisconsin ) instrumentalized the “war criminals question”, since many Americans of German origin lived in the states they represented . Langer intervened successfully for Sandberger.

The Simpson commission set up by the American Secretary of War Kenneth Claiborne Royall finally examined 65 death sentences and established the legality of the proceedings. However, the commission recommended converting 29 judgments to life imprisonment and setting up a permanent pardon. The final report of September 14, 1948 was initially not published. After a temporary freeze of execution, the executions resumed in Landsberg at the end of 1948. The results of the Simpson commission were finally published on January 6, 1949, probably because a commissioner publicly alleged that the commission chairman had withheld evidence of allegations of torture.

"Justice By Grace" - McCloy and the Peck Panel (March-August 1950)

As a result of this growing criticism of the American War Crimes Program , General Thomas T. Handy , the Commander in Chief of the US Army in Europe ( United States European Command ) , set up a pardon commission recommended by the Simpson Commission on November 28, 1949 (War Crimes Modification Board) for those convicted of the Dachau trials . The American High Commissioner John McCloy , who held the pardon for those convicted of the Nuremberg Trials , set up a corresponding equivalent in March 1950. The three-member Advisory Board on Clemency for War Criminals was commonly called the Peck Panel after its chairman, David W. Peck . In principle, according to McCloy, “justice by grace” should be exercised. For the twenty convicts from the Einsatzgruppen trial still in American custody, the Peck Panel recommended on August 28, 1950 that the death penalty be retained in seven cases. Four times the death penalty should be commuted to imprisonment and three times the sentence should be reduced. Six convicts were to be released immediately after the recommendation, two of whom had received a death sentence at the trial.

A pardon for Radetzky was justified by the Protestant pastor Karl Ermann from Landsberg, for example, as follows: “In December 1948, at the request of the priest, he took on the task of creating a nativity play with a group of prisoners , which is then played on Christmas Eve in the prison church has been. At Christmas 1949 he designed a Christmas evening with songs, poetry and music. [...] In many evenings with the theme of 'chamber music and poetry', he knew how to introduce his fellow prisoners to the world of classical German poetry and music. [...] I am certain that it will prove itself very well outside and that it will not be able to contribute insignificantly to strengthening our people's willingness to build up forces. "

Public pressure and McCloy's decision (September 1950 to January 1951)

The public protest finally manifested itself during a demonstration in Landsberg on January 7, 1951. Up to 4,000 participants from Landsberg am Lech and the surrounding area met at 11 o'clock on Landsberger Hauptplatz to oppose the resumption of executions and for the pardons of the prisoners to demonstrate in the Landsberg War Crimes Prison. Loudspeaker trucks drove through Landsberg in advance on behalf of the city administration to call on residents to take part in the demonstration. In addition to members of the Bundestag Gebhard Seelos from the Bavarian Party and Richard Jaeger from the CSU , representatives of the Bavarian State Parliament , the churches and the local authorities also took part. Several Jewish Displaced Persons , who had also come to Landsberg to commemorate the more than 90,000 Jews murdered by Einsatzgruppe D, disrupted the rally by heckling like “mass murderers” when Seelos spoke of Ohlendorf and other inmates of the Einsatzgruppen trial. The police used rubber truncheons against the Jewish counter-demonstrators. Even anti-Semitic slogans such as "Jews out" should be dropped, as the Süddeutsche Zeitung after the demonstration said. At the height of the pardon campaign at the turn of the year 1950/51, McCloy received death threats and was then protected, along with his family, by bodyguards. Even the SPD chairman and former concentration camp inmate Kurt Schumacher and Sophie Scholl's sister , Inge Scholl, protested against the executions. Helene Elisabeth, Princess of Isenburg , known as the "mother of the Landsberg prisoners" and later President of the Silent Aid , went to McCloy's wife personally so that she could lobby for pardons for her husband.

The protests finally had an effect. The sentences of the 89 prisoners of the Nuremberg Trials at that time were reduced in 79 cases on January 31, 1951. However, it has been confirmed in ten cases, including five death sentences. Of those sentenced to death in the Einsatzgruppen trial, this concerned Blobel, Braune, Ohlendorf and Naumann because of the “enormity of the crimes” as stated by McCloy. Strauch had already been extradited to Belgium on the basis of an extradition request and was also sentenced to death there. However, the sentence was not carried out because of " mental illness ". In the case of the other people sentenced to death in the Einsatzgruppen trial, the death penalty was converted into life imprisonment for Sandberger, Ott, Biberstein and Klingelhöfer. The amendment of the death sentence to life imprisonment in the event of the slightest doubt has been extended, for the sake of appropriateness, to also include those convicted who had committed crimes in the same position and responsibility. Blume's death sentence was reduced to 25, Steimle's to 20, Haensch and Seibert's to 15 each, and Schubert's to ten years in prison. The sentences have also been lowered. Radetzky and Rühl were released in February 1951 after they had served their prison term. The life sentences of Jost and Nosske were reduced to ten years, the 20-year sentence for Six to 10 and for Schulz to 15 and Fendler's 10-year sentence to eight years.

Multiple postponements and execution: the last death sentences (February to June 1951)

In addition to the four confirmed death sentences from the Einsatzgruppen trial, the one against Oswald Pohl was also confirmed. Pohl, previously head of the WVHA , was sentenced to death in the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office trial. Ultimately, those death sentences against Georg Schallermair and Hans-Theodor Schmidt were confirmed, who had been sentenced to death during the Dachau trials in a secondary trial to the Dachau main trial and the Buchenwald main trial . The executioner Sergeant Britt, who had to be trained theoretically by his assistant Josef Kilian, was designated for the executions . The former prisoner functionary Kilian was in Nordhausen main process , which took place during the Dachau trials due to his work as executioners in Mittelbau been sentenced to life imprisonment. John C. Woods , who had carried out the executions in the war crimes prison from mid-1946, had already returned to the USA and died in 1950.

The seven death row inmates were immediately taken to the basement cells of the war crimes prison after this decision was announced. There they were informed by Graham that their death sentences were confirmed and the possibility of submitting a pardon was given. The executions were due to take place after midnight on Thursday, February 15, 1951, and the death row inmates had to surrender their belongings and underwear. On February 15, 1951 at 3:00 am, the United States Solicitor General Philip B. Perlman ordered the suspension of the executions of the seven "red jackets" after intervention by their lawyer Warren Magee in Washington, DC. The executions were then returned to the wing D of the war crimes prison. An execution of the "Red Jackets" scheduled for May 24, 1951, was also suspended on May 25, 1951 following the same procedure.

Another execution date was finally set for June 7, 1951. As early as June 6, 1951, the security measures in the Landsberg War Crimes Prison were tightened. The seven death row inmates received a final visit from their wives on June 6, 1951. On that day, the United States Supreme Court finally denied a motion to postpone executions. At 11:00 p.m., the death row inmates in their cells were informed by Graham of the final Supreme Court decision and the set execution time for midnight. Afterwards they were visited by the two chaplains in their cells. On June 7, 1951, the seven death sentences were finally carried out by hanging in the Landsberg War Crimes Prison between 0:00 and 2:30 a.m. The German Vice Chancellor Franz Blücher and the Federal Minister of Finance Fritz Schäffer were also present during the executions . It was the last of the total of 255 executions carried out in Landsberg after the end of the war. The corpses of Pohl, Naumann and Blobel were buried in the Spöttinger Friedhof in Landsberg and those of the others in their hometowns.

Pardon, reduction in prison term and parole (1951 to 1958)

In August 1955 finally took the in Germany contract agreed parity grace committee consisting of three German and three representatives of the Western Allies, its work. The German members were under strong pressure from the German public after the prisoners were released, while the Allied representatives had to take into account the public opinion there. Even those sentenced to prison terms in the Einsatzgruppen trial were given their freedom "on parole" - with conditions, that is, on probation - in the course of the 1950s . On May 9, 1958, the last four Landsberg prisoners were released, including Ott, Sandberger and Biberstein. Their sentences were converted into limited prison sentences, which retrospectively counted as serving. This ended the War Crimes Program in the Federal Republic of Germany and the work of the pardon committee.

Valuations and effects

In the Einsatzgruppen trial, which was conducted according to constitutional norms, as in the other war crimes trials of the Allies, the constitutional punishment of Nazi crimes was initially in the foreground. According to statements by a member of the Einsatzgruppen who appeared as a witness in the Einsatzgruppen trial, the interrogators did not know the true extent of the crimes in the occupied parts of the Soviet Union. In order not to incriminate the defendants and himself, he himself testified very cautiously. In addition, there was a lack of documents and witnesses to clarify the facts more clearly and thus to specify the responsibility for crimes of individual defendants. The Einsatzgruppen trial, referred to in the contemporary press as the "greatest murder trial in history", did not lead to a broad public discussion, despite extensive reporting.

Nevertheless, in relation to the other Nuremberg follow-up trials, the highest number of death sentences was announced in this trial. The "mercy fever" that began in the late 1940s was not only due to German and partly American supporter propaganda, which vehemently intervened in favor of the convicted. In the course of the Cold War, the Western Allies were very keen to win West Germany as an alliance partner and not to alienate them through supposed “victorious justice”.

After their release from prison, those imprisoned after the Einsatzgruppen trial in Landsberg were also able to receive returnees' compensation and integrate into German society. So Steimle got a job at a pietistic boarding school and Biberstein at the parish association Neumünster . Jost and Blume later worked as business lawyers and Haensch as industrial lawyers. Nosske became legal advisor at a tenants' association, and Six worked as an advertising manager at Porsche-Diesel-Motorenbau . Seibert was employed as a loan officer for an export company, and Rühl, Radetzky, Fendler and Sandberger were employed as commercial employees.

Chief Prosecutor Ferencz announced before the trial that the trial should help to prosecute the killing of people for racial, religious and political motives as genocide . The verdict included the “re-promulgation and further development of international principles”, which should be “equally binding for individuals and nations”. Heribert Ostendorf notes that the Nuremberg trials ultimately failed to achieve the goal of establishing effective international criminal law.

The representation of Ohlendorf, who consistently claimed in his defense strategy that there had been a general "order to kill Jews" before the war against the Soviet Union, was not contradicted by the other defendants during the trial. The thesis that an order to murder the entire Jewish population had been issued before September 1941 was initially adopted by the majority of historians (cf. Nazi research and Holocaust research ). In the 1960s, Nosske and Sandberger moved away from this representation; so Nosske remembered not having received this order until August 1941. This correction that there was not yet a general "order to kill Jews" in June 1941 was confirmed by findings and research on German National Socialist trials involving the crime of "Einsatzgruppen". Due to this fact, the main responsible persons of the task forces acted initially on their own responsibility, the defensive strategy based on the emergency command was therefore lacking the basis.

Later legal processing of the Einsatzgruppen crimes

The crimes of the Einsatzgruppen only penetrated broader public awareness with the Ulm Einsatzgruppen Trial . In the Ulm Einsatzgruppen trial, which was carried out from April 28, 1958 to August 29, 1958, ten former members of the Tilsit task force had to answer for the murder of around 5,500 Jewish men, women and children in the German-Lithuanian border area in the summer of 1941. Among them were the heads of the task force Tilsit Hans-Joachim Böhme , Bernhard Fischer-Schweder and the head of the SD section Tilsit Werner Hersmann . The responsible chief public prosecutor Erwin Schüle evaluated the documents of the Einsatzgruppen trial in Nuremberg, the existing specialist literature, SS personnel files and the surviving "incident reports USSR" in order to clear up the crime. Among the 173 witnesses were six of those who were pardoned in Landsberg during the Nuremberg Einsatzgruppen trial, including Sandberger. In the Ulm Einsatzgruppen trial, all of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to three to fifteen years in prison and a temporary loss of civil rights .

Shocking details emerged during the trial, such as photographs of the criminals at the crime scene after committing the crimes and statements about the drinking after the crime, which were paid for with the victims' money. The mentality of “not wanting to know” then changed in the German population. A majority of the population now spoke out in favor of criminal prosecution for Nazi crimes. The failures in the judiciary and in politics to prosecute Nazi crimes in the 1950s, which became apparent during the Ulm Trial, led the Justice Ministers of the federal states to found the Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the investigation of Nazi crimes in October 1958 . As early as December 1958, this authority began preliminary investigations into the concentration camp and Einsatzgruppe crimes committed abroad , with Schüle as the first director. The evidence about the crimes of the Einsatzgruppen and commandos was evaluated and then investigative proceedings were carried out. Between 1958 and 1983 there were fifty trials of 153 defendants. For example, the leaders of the Einsatzkommandos of the Einsatzgruppen Albert Rapp , Albert Filbert , Paul Zapp received life imprisonment and Otto Bradfisch , Günther Herrmann , Erhard Kroeger , Robert Mohr and Kurt Christmann received early prison sentences. Oswald Schäfer was acquitted due to a lack of evidence, with Bernhard Baatz due to the statute of limitations and with Erich Ehrlinger due to inability to stand trial. Karl Jäger and August Meier committed suicide while in custody. In the GDR , too, there were at least eight proceedings against members of Einsatzgruppen, in which death sentences and life sentences were pronounced.

literature

Primary literature and memoirs

- Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No. 10 . (PDF) Vol. 4: United States of America vs. Otto Ohlendorf, et al. (Case 9: “Einsatzgruppen Case”). US Government Printing Office, District of Columbia 1950, pp. 1-596. (Volume 4 of the 15-volume "Green Series" on the Nuremberg follow-up trials. The volume contains, among other things, indictment, judgment and excerpts from the trial documents. The volume also contains the documents relating to the RuSHA trial .)

- The process documents are in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); the record group numbers relevant to the process are 94, 153, 238, 260, 319, 338 and 446. Essential process documents were published in the form of three microfilm series:

- Records of the United States Nuernberg War Crimes Trials, United States of America v. Otto Ohlendorf et al. (Case 9) . NARA, Washington 1973. (National Archives Microfilm Publication M895, 38 rolls, table of contents (PDF; 668 kB) and finding aid by the editor John Mendelsohn , Washington 1978.)

- Records of the United States Nuernberg War Crimes Trials Interrogations, 1946-1949 . NARA, Washington 1977; National Archives Microfilm Publication M1019, 91 rolls; Table of contents (PDF; 186 kB.)

- Interrogation Records Prepared for War Crimes Proceedings at Nuernberg 1945-1947 . NARA, Washington 1984; National Archives Microfilm Publication M1270, 31 rolls; Table of contents (PDF; 2.0 MB.)

- Telford Taylor (Ed.): Final Report to the Secretary of the Army on Nuernberg War Crimes Trials under Control Council Law No. 10 . US Government Printing Office, District of Columbia 1950.

- Telford Taylor: The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials - a Personal Memoir . Knopf, New York 1992, ISBN 0-394-58355-8 .

- Benjamin Ferencz : From Nuremberg to Rome. A life for human rights. In: Structure. The Jewish monthly magazine. Zurich, Issue 2/2006, ISSN 0004-7813 , pp. 6-9.

- Michael A. Musmanno : The Eichmann Commands. Macrae Smith, Philadelphia 1961. (British licensed edition by Peter Davies, London 1962.)

Secondary literature on the Holocaust against the Jews in the occupied Soviet Union

- Christopher Browning : The Origins of the Final Solution: the Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 - March 1942. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2004, ISBN 0-8032-1327-1 .

- Israel Gutman (ed.): Encyclopedia of the Holocaust - The persecution and murder of European Jews. 3 volumes. Piper, Munich, Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-492-22700-7 .

- Ernst Klee : The dictionary of persons on the Third Reich. 2nd Edition. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-596-16048-8 .

Secondary literature on the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union and the Einsatzgruppen process in the narrower sense

- Andrej Angrick : Occupation Policy and Mass Murder: Einsatzgruppe D in the southern Soviet Union 1941–1943. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-930908-91-3 .

- Donald Bloxham: Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001, ISBN 0-19-925904-6 .

- Hilary Earl: The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial, 1945–1958: Atrocity, Law, and History. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-45608-1 . ( Review on H-Soz-u-Kult.)

- Ronald Headland: Messages of Murder: a Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941-1943. 2nd Edition. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Rutherford (NJ) 2000, ISBN 0-8386-3418-4 .

- Peter Klein (Ed.): The Einsatzgruppen in the occupied Soviet Union 1941/42. Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-89468-200-0 . (Volume 6 of the publications of the House of the Wannsee Conference Memorial and Education Center.)

- Ralf Ogorreck and Volker Rieß: Case 9: The Einsatzgruppen Trial (against Ohlendorf and others). In: Gerd R. Ueberschär (Hrsg.): National Socialism in front of a court. The allied trials of war criminals and soldiers 1943–1952. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-13589-3 , pp. 164-175.

- Robert Wolfe: Putative Threat to National Security as a Nuremberg Defense for Genocide . In: Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (AAPSS), Vol. 450, No. 1 (July 1980), pp. 46-67, doi: 10.1177 / 000271628045000106

Secondary literature on punishment and pardon practice as well as on "politics of the past" in the Federal Republic

- Ludwig Eiber and Robert Sigel (eds.): Dachauer Trials - Nazi crimes before American military courts in Dachau 1945–1948. Wallstein, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-8353-0167-2 .

- Norbert Frei : Politics of the past: the beginnings of the Federal Republic and the Nazi past. Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-41310-2 .

- Kerstin Freudiger: The legal processing of Nazi crimes. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002. ISBN 3-16-147687-5 .

- Thomas Raithel: The Landsberg am Lech prison and the Spöttinger cemetery (1944–1958). Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-58741-8 . (Documentation on behalf of the Institute for Contemporary History Munich, review in Sehepunkte , Vol. 9 (2009), No. 6.)

- Thomas Alan Schwartz: The pardon of German war criminals - John J. McCloy and the inmates of Landsberg. In: Institute for Contemporary History Munich (Ed.): Quarterly Issues for Contemporary History . 38th volume, issue 3, 1990, ifz-muenchen.de (PDF; 1.6 MB).

Web links

- Video collection on the Nuremberg trials of the Robert H. Jackson Center, including Ohlendorf testimony before the IMT (1946), recordings from the Einsatzgruppen trial (1947/48) and memories of Benjamin Ferencz (2008)

- Nuremberg Trials and Tribulations - Public Prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz's memories of the Nuremberg trials and the Einsatzgruppen trial

- Ohlendorf, et al. (Case No.9): Einsatzgruppen Case. Legal Tools Project ; Indictment and Judgment

- Hilary Earl: The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial, 1945–1958 . ISBN 978-0-521-45608-1 ; on the Cambridge University Press website (introduction, table of contents, conclusion, index)

References and footnotes

- ↑ Johannes Hürter: Hitler's Army Leader: The German Supreme Commanders in the War against the Soviet Union 1941/42 . 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-486-58341-7 , pp. 520-521.

-

↑ a b References to the number of victims:

- Leni Yahil, Ina Friedman and Haya Galai: The Holocaust: the Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945 . Oxford University Press US, 1991, ISBN 0-19-504523-8 , p. 270, Table 4 “Victims of the Einsatzgruppen Actions in the USSR” gives 618,089 victims of the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union.

- Ronald Headland: Messages of Murder , 2nd edition. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Rutherford (NJ) 2000, p. 124 gives the number of victims under the responsibility of the Einsatzgruppen, including other German police units and collaborators , as more than one million people.

- Helmut Langerbein: Hitler's Death Squads: The Logic of Mass Murder . Texas A&M University Press, College Station 2004, ISBN 1-58544-285-2 , pp. 15-16 gives the number of victims on Soviet territory by the Einsatzgruppen in connection with other SS units, the Wehrmacht and the police with about one and a half Millions of people, but at the same time emphasizes the difficulties of estimating and delimiting.

- ^ Benjamin Ferencz : Opening Statement of the Prosecution , presented on September 29, 1947. In: Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No. 10. , Vol. 4. District of Columbia 1950, p. 30.

- ^ Völkischer Beobachter of October 10, 1938.

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: The Order under the Skull - The History of the SS , Augsburg 1998, p. 324 f.

- ^ Adolf Hitler's order to carry out "special measures" at "Operation Barbarossa". Quoted in: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust ; Piper Verlag, Munich 1998, Volume 1, Page 395 f.

- ↑ a b c Israel Gutman: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust ; Piper Verlag, Munich 1998, volume 1, page 393 ff.

- ↑ a b Heinz Höhne: The Order under the Skull - The History of the SS , Augsburg 1998, p. 330.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Ralf Ogorreck and Volker Rieß: Case 9: The Einsatzgruppen Trial (against Ohlendorf and others) , Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 165 f.

- ↑ a b Action 1005 on www.deathcamps.org

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: The Order under the Skull - The History of the SS , Augsburg 1998, p. 332.

- ^ Testimony of the Wehrmacht member Rösler before the International Military Tribunal quoted from: Heinz Höhne: The Order under the Skull - The History of the SS , Augsburg 1998, p. 322.

- ↑ English He wrote the Einsatzgruppen case . Donald Bloxham: Genocide on Trial . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001, pp. 188-189.

- ^ Hilary Earl: The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial . Cambridge 2009, pp. 49-50.

- ^ Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal , Vol. IV, pp. 311-355 . (Volume 4 of the Blue Series .)

- ^ Telford Taylor: The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials . Knopf, New York 1992, p. 246.

- ^ Hilary Earl: The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial . Cambridge 2009, pp. 192-193.

- ^ Hilary Earl: The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial . Cambridge 2009, pp. 226-227.

- ^ A b c Ronald Headland: Messages of Murder , 2nd edition. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Rutherford (NJ) 2000, pp. 12-15.

- ^ A b c Ronald Headland: Messages of Murder , 2nd edition. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Rutherford (NJ) 2000, p. 13.

-

^ First report from Walter Stahlecker , commander of Einsatzgruppe A, to the RSHA from October 16, 1941, on the activities of Einsatzgruppe A in the occupied Baltic States and in Belarus up to October 15, 1941. ( Excerpt ( memento of the original from November 12th 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. In English on the website of the University of the West of England in Bristol.) Second report by Franz Stahlecker on the actions of Einsatzgruppe A for the period from October 16, 1941 to January 31, 1942.

- ↑ Karl Jäger , leader of the Einsatzkommando 3, to the commander of the Security Police and the SD from December 1, 1941, about the "executions" carried out in the area of EK 3 up to December 1, 1941. ( Hunter report as a scan and as a transcription.)

- ↑ Ronald Headland: Messages of Murder , 2nd edition. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Rutherford (NJ) 2000, pp. 46-47.

-

↑ According to Heinz Schubert's statement, only their commander Ohlendorf , his deputy Seibert and the radio operator Fritsch in Einsatzgruppe D had access to their own Einsatzgruppen radio messages. Schubert himself, von Ohlendorf's adjutant, received the reports for filing, although the number of victims was omitted from the reports. These numbers were handwritten by Ohlendorf or Seibert before the courier dispatch.

Records of the United States Nuremberg War Crimes Trials , Vol. 4. United States Government Printing Office , District of Columbia 1950, p. 98. - ↑ Astrid M. Eckert: Battle for the files: the Western Allies and the return of German archives after the Second World War . Steiner, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-515-08554-8 , pp. 68-69.

- ^ A b c d e Hilary Earl: The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial . Cambridge 2009, SS 75-79.

- ↑ Ronald Headland: Messages of Murder , 2nd edition. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Rutherford (NJ) 2000, p. 14.

- ↑ Benjamin Ferencz : CHAPTER 4: Nuremberg Trials and Tribulations (1946–1949), Story 32: Preparing for Trial ( Memento of the original from March 14, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: “Benny Stories” on Benjamin Ferencz's website. (Retrieved October 13, 2009.)