European Union energy policy

The European Union (1993) was originally formed from the European Coal and Steel Community ( ECSC , 1951), the European Economic Community (EEC, 1957) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAG, 1957). Despite the communitarisation of sub-areas of energy generation and distribution ( coal and nuclear power ), for decades it lacked a coherent energy policy approach. This has only gradually started to change since 1996 and intensifies from 2006 onwards.

The start of the new millennium was a green paper presented by the EU Commission on a “sustainable, competitive and secure energy supply”, which opened a broad debate about an independent energy policy for the European Union. Following statements from various EU institutions, the Commission presented a revised energy strategy in January 2007 that defines key goals (particularly in relation to climate protection and renewable energies ) and proposes specific bundles of measures to achieve them. At the spring summit of the European Council in March 2007, the heads of state and government largely approved the Commission's proposals and adopted an energy policy action plan. In September 2007 the EU Commission presented the first concrete legislative proposals, others have followed at short intervals since then.

Legal bases

With the Treaty of Lisbon , European energy policy was given an independent legal basis in primary law for the first time ( Art. 194 TFEU ). As a result, the goals of “security of supply” and “economic efficiency of energy supply” can now also be explicitly pursued. Previously it was all about environmental protection and the free energy market (energy as a commodity within the meaning of Art. 28 ff. TFEU).

The field of nuclear technology and research has been covered by the Euratom Treaty since 1957 . Until the Treaty of Lisbon came into force, legal acts of energy policy were generally based either on Article 95 of the EC Treaty (internal market) or Article 175 of the EC Treaty (environmental policy).

Decisions on energy policy measures are generally made within the EU in the ordinary legislative procedure , i.e. jointly by the Council and Parliament . According to Art. 192 TFEU, measures that affect the choice between different energy sources, i.e. the energy mix of the member states, can only be taken unanimously.

Strategic approach

The European debate about a coherent strategic approach began with the Green Paper on “sustainable, competitive and secure energy supply” presented in March 2006 . After a phase of public consultation, in January 2007 the Commission presented a revised Energy Strategy (Strategic Energy Review I). The European Council essentially confirmed this strategy at the spring summit in 2007 and decided that the EU energy strategy should be reviewed every two years.

The EU's energy strategy is geared towards achieving three long-term goals at the same time. The EU wants to combat climate change, which dampens the external vulnerability of the EU due to its high dependency on imports of fossil fuels, and promotes growth and employment through a competitive energy supply. The Commission expressly maintains the assumption that all of these challenges can be met at the same time. The potential for conflict between these long-term goals is not addressed in the energy strategy, and priorities are not explicitly set. Instead, the strategy is pervaded by the assumption that the three target areas and the appropriately aligned bundles of measures are mutually supportive.

In the Strategic Energy Review I, any definition of which criteria would have to be met in order to be able to regard a long-term goal as achieved was avoided - which should make a later evaluation of European energy policy much more difficult. This deficiency was not eliminated in the Second Strategic Energy Review either. This “second review” of the energy strategy was presented by the Commission in November 2008 and contained, above all, clarifications on the issue of security of supply.

In autumn 2010 the commission presented the draft of an expanded energy strategy with long-term goals for 2050, as well as an update of the energy action plan, valid for the period 2011-2020. The focus of the EU energy strategy is on the internal energy market, energy efficiency, consumer protection, research and development and the EU's external energy relations.

In his inaugural address, the new EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker announced the establishment of an "Energy Union" in order to reduce dependence on fossil raw material imports, increase energy efficiency and make Europe the world leader in the expansion of renewable energies. The most important cornerstones of the new strategy are energy security, especially with regard to the dependence of Eastern European countries on Russia, a uniform energy market, which requires, among other things, the expansion of electricity and gas networks, the decarbonization of the economy, and the EU back to number one to make renewable energies. Other pillars are energy efficiency and research and development.

Fields of action

The “An Energy Policy for Europe” action plan, which was adopted by the European Council in March 2007 on the basis of the energy strategy, defines five areas in which work is to be carried out to achieve the three long-term energy policy goals. The European Union has been active in all of these fields of energy policy for a long time, but with only weak political will. The target of a greenhouse gas reduction of 20% by 2020, which is particularly emphasized in the communication of the EU, forms the basis of the energy action plan. However , due to the inherent logic of European legislation , the area of “(international) climate policy ” is not an explicit part of the Energy Action Plan . The Directorate-General for Transport and Energy is not responsible for climate policy instruments such as EU emissions trading or the CO 2 emission ceilings for cars , but the Directorate-General for the Environment.

Internal gas and electricity market

The creation or completion of an EU-wide internal energy market has been at the center of the European Union's energy policy for years. The EU's aim is to apply the principles of the internal market to energy-type goods as well. This requires special regulations , especially for line-based energy sources ( natural gas and electricity ). Electricity and gas networks represent so-called “ natural monopolies ”. Companies that have these transport infrastructures - usually (formerly) state-owned energy providers - can easily hinder the entry of competitors into the market. This usually happens through excessive network usage charges or the inadequate expansion of network capacities, especially in the case of cross-border lines, the so-called coupling points. In EU member states with insufficient market liberalization and / or only weak regulatory authorities, it is therefore only possible under difficult conditions for (domestic and international) energy producers to effectively compete with the original monopoly on their home markets. The private and commercial final energy consumers therefore have only very limited options to freely choose their gas or electricity supplier (see also: Switching electricity providers ).

- Status quo of policy making at EU level

The problems in the gas and electricity sectors were recognized early on by the EU, but to date it has proven difficult to resolve them across the EU. Through the “ Trans-European Networks Energy” (TEN-E) program, the EU has so far only been moderately successful in promoting the expansion of cross-border network connections. The first liberalization guidelines were issued in the mid / late 1990s, and due to numerous deficiencies in implementation, so-called acceleration guidelines followed in 2003. These envisaged the completion of the internal energy market by July 1, 2007. While the EU Commission is making every effort to create a real internal energy market (partly also through anti-trust measures) and is supported in this by Parliament and a few member states (e.g. Great Britain and the Netherlands), member states such as France are proving themselves , Germany or Austria actually act as the brakes, even if they do not question the official EU target.

- Planned measures

It is undisputed among all the relevant EU bodies and the member states that new legal and regulatory measures are required in order to come much closer to achieving the internal market goal in the energy sector. The focus of the discussion will be the effective unbundling of production (electricity) or imports (gas) and the availability of energy networks. This is intended on the one hand to guarantee non-discriminatory access for any energy provider to the networks, and on the other hand to provide incentives to expand network capacities as required. Hard arguments are to be expected over the various unbundling options. While the Commission, Parliament and some liberalization-friendly member states are advocating "ownership unbundling" which would oblige the large energy suppliers to sell their networks, Member States who are skeptical of liberalization want the energy suppliers only to cede the networks to a formally independent trustee, but continue to do so Remain owner of the infrastructure. Also controversial is the so-called “ Gazprom clause”, which prohibits companies with restrictive market access conditions in their home countries from buying into the liberalized European energy sector.

- Current innovations

In September 2007 the EU Commission presented the third package on the internal energy market, consisting of five legislative proposals. This includes regulations on the electricity and gas market and the establishment of the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulatory Authorities (ACER). In summer 2009, shortly before the end of the parliamentary term of office, the entire package could be adopted in the second reading (co-decision procedure). In particular, a group around Germany has prevailed with its demands for a third unbundling option (ITO), so that the mandatory ownership unbundling of the energy companies is off the table. Most of the measures, including the start of work for ACER (based in Ljubljana , Slovenia ), are due to be implemented in March 2011.

Energy security

Ensuring energy security is one of the three main objectives of EU energy policy. The future provision of sufficient energy at reasonable prices is at least questionable for two reasons. On the one hand, there is a risk that the increasing dependency on imports will be offset by insufficient supply quantities for crude oil , natural gas and uranium ( coal is relatively unproblematic in this regard). On the other hand, there is a considerable need for the expansion of energy infrastructures (electricity power plants and lines, gas pipelines, liquefied natural gas terminals). In the event of a crisis, it would have to be ensured that the EU member states can support one another. An EU energy security policy basically takes two types of actor constellations into account. On the one hand, the difficult relationship between the EU (or individual European energy supply companies) and countries supplying oil, gas and uranium; on the other hand, the relationship between the EU, the member states and the European energy supply companies.

A paper by members of the European Parliament draws attention to the rising trade balance deficit due to import costs for fossil fuels, which in particular is also worsening the debt crisis in the EU countries. The import dependency cost the 27 EU countries between October 2010 and September 2011 408 billion euros. In contrast, the current account deficit in the same period was only 119 billion euros.

- Status quo of policy making at EU level

The EU's options for action are limited in relation to the countries that supply oil, natural gas and uranium. Since, with the exception of the Energy Charter Treaty (which Russia has not ratified), there are no binding legal frameworks for international energy markets, the EU remains relegated to rather non-binding energy dialogues with producer countries. In the “inward” political dimension, the EU's scope for action is considerably greater, but has only been used to a limited extent so far. Through the “Trans-European Energy Networks” (TEN-E) program, it promotes the cross-border linking of the member states' gas and electricity networks as well as the planning of import pipelines (e.g. Nabucco pipeline ) and liquefied natural gas terminals (LNG). In addition, the EU member states have stockpiling obligations for crude oil , which, however, only complement a similar crisis reaction mechanism of the International Energy Agency .

- Planned measures

EU Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger presented a strategy for a secure European energy supply in May 2014. This includes the diversification of foreign energy supplies, the expansion of the energy infrastructure, the completion of the EU internal energy market and energy-saving measures. In addition, it contains specific proposals to secure the energy supply in the coming winter.

The German Renewable Energy Association (BEE) criticized the EU Commission for relying too heavily on nuclear power and fossil fuels with unrealistic and controversial options such as shale gas and underground storage of carbon dioxide (CCS), and called on the European Commission to develop a strategy for a sustainable energy supply and to describe as soon as possible the way to a secure energy system that focuses on domestic renewable energies.

Energy efficiency and renewable energies

Increasing energy efficiency and expanding the share of renewable energy sources can make a significant contribution to achieving the three main goals. Increased energy efficiency and a larger share of renewables bring about a relative reduction in greenhouse gases and reduce the relative dependency on the import of fossil fuels. Investments in energy efficiency generally also increase the competitiveness of an economy. Particularly in the new member states of Central and Eastern Europe, the corresponding potential is still very high. According to forecasts by the oil company BP , renewable energies in the EU will increase by 136% between 2013 and 2035 (compared to natural gas: +15%; oil: −23%; coal: −54%) and CO 2 emissions by 25% sink.

Renewable energy

The EU has set binding targets in the field of promoting renewable energy sources. By 2020 it wants to increase the total share of final energy consumption in the EU on average to 20 percent. In order to achieve this overall target, each member state is assigned different targets in the Renewables Directive passed in April 2009. However, member states are allowed to meet their obligations to a limited extent by making purchases abroad.

In a roadmap presented in 2011, the EU Commission presented various scenarios and potential calculations for the development of renewable energies up to 2050. In the opinion of the German Federal Environment Ministry , environmental associations and the Federal Association for Renewable Energy , the calculations underestimate the potential of renewable energies.

On January 22nd, 2014, the EU Commission announced its energy and climate policy goals for 2030. According to this, a target of 27 percent for the share of renewable energies in gross final energy consumption in the EU and a reduction in CO 2 emissions of 40% by the year 2030 is aimed for. The Federal Association for Renewable Energy and environmental associations, on the other hand, are calling for a minimum target for renewable energies in the European energy supply of 45 percent and a CO 2 reduction of 60 percent by 2030. The Science and Politics Foundation expects the measures already decided to achieve a greenhouse gas reduction of up to 32 percent In 2030. One year after taking office, however, the climate and energy targets have not yet been implemented.

Energy efficiency

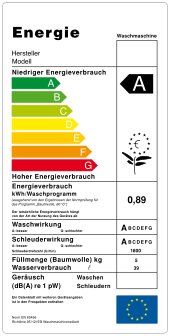

In the area of energy efficiency, there are several detailed guidelines that relate to individual processes and device types (household, building, energy services, etc.). In some cases, the consumption standards of specific product groups (e.g. lamps or stand-by switches) are set in the comitology procedure. In addition, an overarching action plan is intended to ensure that energy efficiency in the EU increases by one percent annually between 2008 and 2017. However, this goal is not mandatory. Member States only have to present annual action plans, the first time in summer 2007.

In July 2014, the European Commission proposed a target of 30% higher energy efficiency by 2030. New perspectives for European companies were named as goals, as well as affordable energy prices for consumers, more security of supply through a noticeable decrease in natural gas imports and positive environmental effects. It is assumed that the EU's gas imports will decrease by 2.6% for every additional percent of energy saved, thus reducing Europe's dependence on third country imports. So far, a target of only 20% has applied, which the EU member states have agreed on.

The Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research and the German Institute for Economic Research , on the other hand, recommend an energy efficiency target of 40% as the economically most sensible path. The calculation models used by the EU would underestimate the cost of energy, but overestimate the cost of efficiency measures.

The EU Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27 / EU) introduced legally binding measures in 2012 to ensure that the goal of 20% more efficient energy use can be achieved by 2020. So far, Italy, Cyprus, Denmark, Malta and Sweden have communicated the full implementation of the Energy Efficiency Directive in national law. The deadline for implementation was June 5, 2014.

Energy technologies

The EU's ambitious energy policy goals can only be achieved if technological progress in the field of energy technologies advances rapidly. This applies, for example, to CO 2 capture and storage (sequestration) when burning fossil fuels, alternative drives in the transport sector (hydrogen or biofuels) as well as improvements in energy efficiency technologies or energy storage. The development and market launch of innovative technologies can be driven not only through regulatory measures, but also through the allocation of research funds.

- Status quo of policy making at EU level

In the 6th and 7th research framework programs of the EU, funds were or are being made available for the promotion of energy technologies. However, these programs are only inadequately interlinked with national funding measures. The total volume is also relatively low (2002–2006: 2.2 billion euros). In December 2008, a guideline on the geological storage of captured CO 2 was passed.

- Planned measures

At the end of 2007, the EU Commission presented a draft “Strategic Plan for Energy Technology”, which was confirmed by the 27 heads of state and government at the spring summit of the European Council in March 2008. One of the central measures will be to develop a system for promoting demonstration power plants in which the large-scale application of CO 2 capture and storage (CCS) can be tested.

- Current legislative proposals

The adoption of the “Strategic Energy Technology Plan” by the European Council has not yet resulted in any concrete legislative proposals. The promotion of energy technologies can most likely be expected within the framework of the CCS legislation. A directive passed in December 2008 regulates the geological storage of separated CCS, the regulation on the energy infrastructure package, which the European Council tentatively agreed in March 2009, also contains grants for several coal-fired power plant projects with CCS.

Energy foreign policy

Foreign energy policy describes an arena that lies at right angles to all other fields of energy policy. It encompasses all measures that do not regulate energy relations within the EU, but rather structure energy-political relations with actors beyond the EU's borders, regardless of whether they are energy supply companies, governments (especially those of producer and transit countries) or international organizations (like IEA or OPEC ). Foreign energy policy is largely focused on creating security of supply, but is by no means limited to it. Measures such as the targeted export of energy efficiency programs, energy technologies or the legal framework for the internal energy market are also part of the EU's external energy policy. In the EU's legislative logic, the majority of measures are understood as part of EU foreign policy. Foreign energy policy is therefore fundamentally not part of the supranational 'First Pillar' of the EU. Accordingly, the decisions require a unanimous vote from all member states. This explains the frequent emphasis on the principle that in EU external energy policy all member states should, if possible, “speak with one voice”.

- Status quo of policy making at EU level

The focus of EU external energy policy is currently on the so-called "energy dialogues", especially with producer countries (e.g. Russia , Algeria , Norway ), regions (especially Central Asia) and organizations (e.g. OPEC). As a rule, however, these dialogues hardly go beyond pure consultations, and only in the rarest of cases do they lead to contractual agreements, the legally binding nature of which is also weak. The situation is similar with the increasing integration of energy policy aspects into the European Neighborhood Policy . The establishment of the 'European Energy Community' is endowed with a much stronger legally binding force. In this context, on July 1, 2007, all south-eastern European non-EU states committed themselves to adopting the internal energy market rules applicable in the EU. This is intended to ensure that transparent investment rules also apply beyond the EU borders. From the EU's point of view, this is particularly important to secure the transit of pipeline-bound oil and gas supplies. The non-EU states are hoping for a higher inflow of foreign investments, especially when expanding their power grids.

- Planned measures

The EU has announced that it intends to become more active in all sub-fields of international energy policy in the future. It plans to expand the energy dialogues, to intensify the integration of energy policy aspects into the newly negotiated partnership and cooperation agreement with Russia, to expand the European Energy Community to Norway, Moldova, Ukraine and Turkey and to conclude an international agreement to promote energy efficiency.

See also

- Energy union

- Ecodesign Directive

- European Union climate policy

- Energy transition by country

- Desertec

literature

- David Buchan: Why Europe's energy and climate policies are coming apart. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Oxford 2013

- Severin Fischer: Energy and climate policy in the Lisbon Treaty. Legitimacy extension for growing challenges. (PDF; 154 kB) In: integration 1/2009, pp. 50–62

- Severin Fischer: On the way to a common energy policy. Strategies, instruments and policy making in the European Union, Baden-Baden 2011.

- Severin Fischer: Nord Stream 2 - Trust in Europe. CSS Policy Perspectives , No. 4/4, March 2016

- Oliver Geden / Susanne Dröge: Integration of the European energy markets. Necessary prerequisite for an effective EU external energy policy. (PDF; 285 kB) SWP study , S13, Berlin 2010.

- Oliver Geden / Severin Fischer: Moving Targets. The negotiations on the EU's energy and climate policy goals after 2020. (PDF; 423 kB) SWP study , S1, Berlin 2014.

- Johannes Pollak / Samuel Schubert / Peter Slominski The EU's energy policy. Vienna 2010

- Sébastien Rippert: The Energy Policy Relations between the European Union and Russia 2000–2007. European and Russian interests in the field of tension between rapprochement and alienation. Bonn 2009 *

- Kirsten Westphal: Russian natural gas, Ukrainian pipes, European security of supply. Lessons and consequences from the gas dispute 2009 SWP study , 18, Berlin 2009.

- Tobias Woltering: European foreign energy policy and its legal basis , Frankfurt am Main 2010.

Web links

- EurActiv Energy Policy rubric

- EU entry page "Energy"

- Topic dossier "EU energy policy" from the Science and Politics Foundation

- European Council (Brussels, March 8/9, 2007) - Conclusions of the Presidency with an Action Plan “An Energy Policy for Europe” (PDF file; 221 kB)

- European Commission (January 10, 2007) - An Energy Policy for Europe (PDF file; 141 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Preparatory work in the field of energy policy and energy law , especially renewable energy sources, has been visible since 1983. See for example: Council of the Community, resolution on a Community orientation for the further development of new and renewable energy sources, OJ. C 316 v. December 9, 1986, pp. 1-2

- ^ BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2016 on bp.com

- ↑ Second Strategic Energy Review ( Memento of the original from December 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. from November 2008 (English)

- ↑ bmwi.de: Brüderle welcomes the priorities of the new EU energy strategy ( memento of the original from January 14, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Press release, November 10, 2010, accessed December 23, 2011

- ^ A New Start for Europe: My Agenda for Jobs, Growth, Fairness and Democratic Change

- ↑ Sustainability Council: The Limits of the European Energy Union ( Memento of the original from January 30, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. dated February 11, 2015

- ↑ Working paper by Sven Giegold MEP and Sebastian M. Mack ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 13.5 MB)

- ↑ EC: Energy: Commission presents strategy to strengthen security of supply. May 28, 2014

- ↑ BEE: BEE calls for an EU strategy for sustainable energy supply. 19th June 2014

- ↑ BP Energy Outlook 2035. Energy trends and data - EU

- ↑ Energy Roadmap 2050: a secure, competitive and low-carbon energy sector is possible European Commission - IP / 11/1543 15/12/2011

- ↑ EU Energy Roadmap 2050 underestimates the potential of renewable energies, press release from December 15, 2011

- ↑ Sustainability Council: Wrong assumptions? Criticism of the EU Commission's Energy Roadmap 2050. January 10, 2012

- ↑ FAZ: EU Commission receives a lot of criticism for climate plans ; Press Release: Climate and energy policy goals for a competitive, safe and low-carbon EU economy by 2030. European Commission - IP / 14/54 22/01/2014

- ↑ Position paper: Energy turnaround for Europe: An ambitious EU climate and energy package for climate protection, investment security and cost efficiency ( Memento of the original dated February 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; BUND: "EU Commission has no ambition whatsoever when it comes to climate protection": BUND's comment on the EU Commission's climate protection goals. January 22, 2014 ; NABU: NABU: Europe is threatened with a backward flip on climate policy. January 21, 2014

- ↑ Position paper of the BEE

- ↑ SWP: New EU Energy and Climate Goals: German Energiewende under pressure to adapt. January 21, 2014

- ↑ BEE: EU as No. 1 in renewable energies? The implementation is still pending. One year of the Juncker Commission - a balance sheet from an energy policy perspective. Background paper, Nov. 2015

- ↑ European Commission: European Commission proposes higher and more realistic energy savings target for 2030. 23rd July 2014

- ↑ Fraunhofer ISI: The role of an ambitious energy efficiency target in the frame of a 2030 target system for energy efficiency, renewables and greenhouse gas emissions. Research project

- ↑ Sustainability Council: Experts doubt the invoices for energy and climate plans by the EU Commission. News from July 31, 2014

- ↑ Directive 2012/27 / EU (PDF) (Energy Efficiency Directive)

- ↑ cf. “Energy efficiency - now or never!” EP rapporteur Claude Turmes in dialogue with stakeholders at the EBD. European Movement Germany, February 29, 2012, accessed June 8, 2012 .