Erfurt Union Constitution

On the basis of the Erfurt Union Constitution (originally: Imperial Constitution ), a German federal state was to be created in 1849/50 . The draft constitution of May 28, 1849 was based on the Frankfurt constitution of March 28, 1849. The project of an Erfurt Union was supported by the Kingdom of Prussia . It wanted to lead a small German state, but on the basis of a constitution that was more conservative than the Frankfurt model.

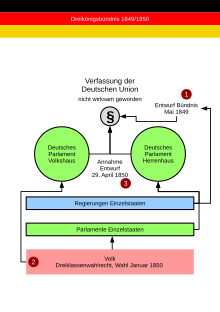

The draft constitution of May 28, 1849 was amended by an additional act on February 26, 1850 , which adapted it to current events. This also included the change of name of the state from Reich to Union . The Erfurt Union Parliament of March and April 1850 discussed the constitution, but accepted the draft as a whole.

From the perspective of the liberal parliamentary majority, the Union was thus founded; the changes demanded by the governments and conservatives should have been decided retrospectively according to the rules of the constitution. On April 29, in the last session, the majority passed proposals for liberal and unitary changes to the governments, which they were free to take into account. In spite of the overly accommodating liberals, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV no longer consistently pursued the union project. The project and with it the provisional validity of the Union constitution ended after the autumn crisis of 1850 at the latest .

Origin and content

On April 28, 1849, Prussia invited the other German states to a meeting in Berlin to discuss a constitution for Germany. On May 9, Prussia sent the draft of a Union Act. While the small states and Württemberg still felt bound by their acceptance of the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution, representatives from Austria, Bavaria, Hanover and Saxony appeared on May 17th. Prussia, Hanover and Saxony finally agreed in the three kings alliance to found a federal state.

On May 28, 1849, a draft for the constitution of the German Empire of May 26, 1849 was published, which the three allied governments adopted as a provisional order. The draft is now often abbreviated as EUV, for Erfurt Union Constitution. He adhered largely to the Frankfurt Constitution (FRV), both in structure and in the formulations. Two thirds of the provisions from the FRV can be found literally in the EUV. Instead of 197, the EUV had 195 paragraphs. However, the TEU strengthened the government vis-à-vis the parliament and gave the individual states more rights. Hans Boldt: "The Frankfurt constitutional compromise was shifted to the right, so to speak," because the FRV was based on an understanding between liberals and democrats, while the TEU was a compromise between liberal ideas and the governments. An official interpretation appeared in a memorandum of the three allied governments dated June 11, 1849.

State and states

While the FRV spoke of the previous federal territory and Austria still kept the way into the Reich open, the TEU assumed from the outset that the relationship with Austria would have to be regulated separately. Those states that wanted to belong to the Union should belong to it (§ 1 TEU). In contrast to the FRV, which is more of a unitary state, the memorandum speaks of the fact that the Union should only do what the individual states are unable to do ( principle of subsidiarity ). In addition, the federal state should no longer be allowed to levy its own taxes, but should be dependent on matricular contributions from the individual states, as was later realized in the German Empire .

head

The head of the German federal state, for which the constitution provided for the King of Prussia , was no longer called Emperor in the EUV , but the Reich and later Union Executive . With regard to the executive, the rights of the Reich executive corresponded to the Frankfurt model. With regard to its legislative rights, however, the Reich Executive Board could only act as part of a new body, the Princely College (Section 65 EUV).

The Princely College was not only allowed to submit bills and postpone the passing of laws, but also to prevent laws, which would have given it an absolute instead of a suspensive veto, as provided in the FRV.

There should be six votes in the Princely College, one each for (Section 67 EUV):

- Prussia;

- Bavaria;

- common for Saxony, Saxe-Weimar, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Saxe-Meiningen-Hildburghausen, Saxe-Altenburg, Anhalt-Dessau, Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Cöthen, Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, Reuss older line, Reuss younger Line;

- jointly for Hanover, Braunschweig, Holstein, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Oldenburg, Lübeck, Bremen, Hamburg;

- jointly for Württemberg, Baden, Hohenzollern-Hechingen, Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, Liechtenstein;

- together for Kurhessen, the Grand Duchy of Hesse, Luxembourg and Limburg, Nassau, Waldeck, Schaumburg-Lippe, Lippe-Detmold, Hesse-Homburg and Frankfurt.

In the event of a tie, the vote of the Reich Executive Committee was decisive. From the point of view of the constitutional political debate so far, the EUV should connect the hereditary emperor with a directorate. The imperial executive had to share certain rights with the other princes.

Parliament and suffrage

The Reichstag was retained with its two-chamber system . However, the state house appointed by state governments and parliaments was upgraded, in which budget law now applied equally to both chambers. Because of the absolute veto for the college of princes and because the budget was to apply for three years, the parliament was given less weight overall.

According to Manfred Botzenhart, the most important change concerned the right to vote. While the Frankfurt electoral law provided for a general, equal and direct right to vote, the Erfurt electoral law established a three-class right to vote . Hanover and Saxony had pushed for this. It was even more restrictive than the Prussian model, since only those who paid a direct state tax and had the right to vote in their place of residence should vote. According to the memorandum of June 11, the Reich legislation should in future also be allowed to enforce the principles of electoral law in the individual states. Because of the heavy weight of Prussia, one should have feared that the three-class suffrage would have been introduced everywhere.

With a three-class electoral system, those entitled to vote vote in three departments (classes), each of which determines an equal number of electors. These electors then decide on the deputies. In the first class there are a few rich, in the second class a larger group and in the third the many other, poorer voters. Because of this inequality, the Democrats rejected the Union and boycotted the elections for the Erfurt Union Parliament at the turn of the year 1849/50. The liberals could come to terms with this, however, if the Frankfurt regulation had actually gone too far for them.

Fundamental rights

The basic rights of the FRV have been weakened in part, with one reservation with regard to state laws for areas in which the federal state was not responsible. The abolition of the death penalty and the nobility as a status were reversed in the TEU, indirect restrictions on freedom of the press are no longer expressly prohibited. In the event of a riot, the freedom of the press should be revoked and special courts allowed. The separation of church and state was weakened. Apart from that, the core of fundamental rights and constitutional guarantees of the FRV remained intact.

Additional files

At the end of February 1850, the Administrative Council of the Union published an additional act to the May draft constitution. At that time the Union Parliament was elected but not yet met, and the events of the past few months had made some changes necessary.

Article 1 of the Additional Act gave the "German Federal State" to be formed the name of the German Union , and the People's and States' House should be called the Parliament of the German Union (instead of the Reichstag ). accordingly, the other designations should be adapted in official language usage or are already being used anew in the text of the additional act (for example Union Board in Art. X, but still: Reich Constitution ).

Some states have not acceded to the Union, namely Bavaria, Württemberg, Holstein, Homburg, Liechtenstein, Limburg and Luxembourg as well as Frankfurt. The two Hohenzollern states became part of Prussia in December 1849. Therefore, the distribution of seats in Parliament has now been adjusted (Art. VII) and the distribution of votes in the Princes' College (Art. VI). However, Hanover and Saxony, although they had turned their backs on the Union on October 20 (Hanover also formally on January 21), were included in the additional file:

- Prussia;

- common for Saxony, Saxe-Weimar, Saxe-Koburg-Gotha, Saxe-Meiningen-Hildburghausen, Saxe-Altenburg, Anhalt-Dessau, Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Koethen, Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, Reuss older line, Reuss younger Line;

- jointly for Hanover, Braunschweig, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Oldenburg, Lübeck, Bremen, Hamburg;

- To bathe;

- together for Kurhessen, the Grand Duchy of Hesse, Nassau, Waldeck, Schaumburg-Lippe, Lippe;

Furthermore, the Additional Act clarifies the relationship between the Union and the German Confederation , which Austria had endeavored to restore since the summer of 1849 at the latest. In the German Confederation, the Union should have and exercise those rights and obligations in common that they previously had individually. In addition, she was responsible for representing the other German states in the German Confederation under international law (Art. III, IV). Entry into the Union was kept open for other states. Such accession should not be viewed as a constitutional amendment, which is why a simple decision by the Union's authorities was sufficient.

Consultation in parliament

Starting position

The Erfurt Union Parliament met on March 20, 1850 to discuss the draft constitution (with additional acts). The administrative council submitted the draft constitution of May 28, 1849, the law for elections to the Volkshaus, the Berlin memorandum of June 11, 1849 and the additional act of February 26, 1850 as documents.

In terms of a constitutional agreement, on the one hand the allied governments and on the other hand the parliament as a representative of the people should jointly bombard the constitution. The Prussian king and most of his ministers thought the draft was still too liberal and pushed for a constitutional revision to bring it into line with the Prussian constitution of 1850.

The liberal majority in parliament, on the other hand, did not want a more conservative constitution and feared long debates that would cause the project to fail. That is how Joseph von Radowitz from the board of directors and Ernst von Bodelschwingh , the actually conservative leader of the liberals in the Volkshaus, thought . In addition, Hanover and Saxony were bound to the previous draft through the Three Kings Alliance. The Liberals therefore agreed early on on the strategy of approving the draft as a whole and returning it unchanged to the governments. In their opinion, the Constitution would enter into force as soon as it was adopted in Parliament, as the governments had already given their approval.

Debates

Radowitz had to reluctantly, under pressure from his king, demand a full, albeit abbreviated, revision in parliament. As a major European power , Prussia should be able to decide on war and peace even without the Union, and the fundamental rights of the TEU should be brought into line with those in the Prussian constitution. The conservative Friedrich Julius Stahl also said that the Union parliament should not have budget rights and that the Reichsgericht should be abolished. The first Union parliament should decide on a permanent budget, which can then only be changed by Reich law. That would have meant that the government would have become independent from parliament on financial matters.

For their part, the liberals endeavored to bring the TEU closer to the Frankfurt model, or at least to make it more liberal and more uniform. Only the Volkshaus should ultimately decide on the budget, not the State House as well. In the case of laws, only the Union Board of Directors should be able to exercise the veto alone, not together with the entire college of princes. With the strengthening of Prussia, they wanted to develop the unified state. Friedrich Daniel Bassermann accused the conservative Schlehdorn parliamentary group of being more Prussian than the king who submitted the draft himself. Stahl betrays the spirit of the Prussian reforms and the wars of freedom and I regret that the nobles can no longer descend from the castles and plunder the merchants. Stahl countered that liberalism wanted to make the king the willless tool of parliament.

Result

But if the governments had blocked the constitution, the state would not have come into being. The Prussian king also threatened this. It became a compromise that the draft was accepted, but the changes requested by the liberally dominated parliament were only proposed as a proposal. They should only come into force if all governments join them. On April 13, 1850, the Volkshaus voted for the adoption of the draft constitution, the memorandum, the electoral bill and the additional act, with 125 votes to 89. In the House of States there were 62 votes to 29 on April 17. In addition, there were the amendments on April 29th. "Furthermore, believed the majority of the members of both houses of the Erfurt parliament, representatives of the people could not have accommodated a government."

On the same April 29, 1850, the President of the Administrative Council, Radowitz, adjourned Parliament. But instead of King Frederick William IV appointing a Union Ministry (government), he sent the documents to the allied governments to discuss them. His mood had changed once again, under the influence of the ultra-conservatives and Russia . This de facto heralded the imminent end of the Union.

rating

According to Hans Boldt, the Imperial Court and fundamental rights were essentially retained in the Erfurt Union Constitution. “It can therefore justifiably be said that with the Union constitution, Germany would have become one of the most progressive states in Europe.” The Erfurt constitution does not have the glamor of the Frankfurt one. But it shows the concessions to the revolution that the governments were ready to make, and not just for tactical reasons, but to promote German welfare through a legal and economic unit. The Bismarckian constitutions of 1867 and 1871 were in many ways in the tradition of the revolutionary era. The Federal Council solution there was obviously anticipated with the princes' college as co-legislator. According to Boldt, this peculiarity still characterizes German federalism.

literature

- Hans Boldt : Erfurt Union Constitution. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne [u. a.] 2000, ISBN 3-412-02300-0 , pp. 417-431.

- Manfred Botzenhart : German parliamentarism in the revolutionary era. 1848-1850. Droste, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-7700-5090-8 (also: Münster, habilitation paper, 1974/1975).

- Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne [u. a.] 2000, ISBN 3-412-02300-0 .

Web links

- Constitution of the German Empire of May 28, 1849, verfassungen.de

Remarks

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here pp. 19–20.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber : German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume 2: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd, substantially revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 , p. 888.

- ↑ Hans Boldt: Erfurt Union Constitution. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 417–431, here pp. 420–421.

- ↑ Hans Boldt: Erfurt Union Constitution. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 417–431, here p. 425.

- ↑ Hans Boldt: Erfurt Union Constitution. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 417–431, here pp. 425–427.

- ↑ Hans Boldt: Erfurt Union Constitution . In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 417–431, here p. 427.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. 1977, pp. 718-719.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. 1977, p. 719.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. 1977, pp. 719-720.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. 1977, p. 719.

- ↑ See Appendix II: Additional Acts on the Draft Constitution of the German Reich. In: Thüringer Landtag Erfurt (Hrsg.): 150 Years of the Erfurt Union Parliament (1850–2000) (= writings on the history of parliamentarism in Thuringia. H. 15) Wartburg Verlag, Weimar 2000, ISBN 3-86160-515-5 , p. 27-44, here pp. 185-187.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume 2: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd, substantially revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 , p. 892.

- ↑ Peter Steinhoff: The "hereditary imperial" in the Erfurt parliament. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 369–392, here p. 371.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament . In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here pp. 34 f.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament . In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here p. 35.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. 1977, p. 769.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. 1977, p. 770 f.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. 1977, p. 771 f.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here p. 37.

- ↑ Peter Steinhoff: The "hereditary imperial" in the Erfurt parliament. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 369–392, here p. 383.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume 2: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd, substantially revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 , pp. 897 f.

- ↑ Hans Boldt: Erfurt Union Constitution. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 417–431, here p. 428.

- ↑ Hans Boldt: Erfurt Union Constitution. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 417-431, here pp. 429 f.