Eugène Dubois

Marie Eugène François Thomas Dubois (born January 28, 1858 in Eijsden , Netherlands , † December 16, 1940 in Haelen , Netherlands) was a Dutch doctor and anatomist . Dubois is considered to be the first researcher to search specifically for the ancestors of man . He became internationally known as the discoverer of the so-called Java man (1891) from a bank wall in Trinil on the Indonesian island of Java . They were the first hominini fossilsthat were discovered outside of Europe and, after the Neanderthals, the second evidence for fossil relatives of anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ).

Research in South Asia

Dubois father was a pharmacist and mayor of his home town Eijsden. After his training as a doctor and his dissertation submitted in 1884, Eugène Dubois researched as assistant to Max Fürbringer at the Universiteit van Amsterdam in the field of comparative anatomy . Influenced by the writings of Ernst Haeckel , who suspected a hypothetical prehistoric man (" Homo primigenius or Pithecanthropus primigenius ") in southern Asia in his work Natural Creation History in 1868 , Dubois resigned in Amsterdam in 1887 and took a position as a military doctorof the Royal Dutch-Indian Army in the Dutch East Indies (now: Indonesia) and sailed with his wife Anna, who had married the year before, and their baby to Padang on Sumatra : “Because of his knowledge of literature, he was convinced that the fossils that were on the Human evolution provide information that could be found in the tropics . Lived there not even the great apes ? Hadn't the tropics been spared the destructive forces of the glaciers that crushed Europe during the ice ages ? […] The East Indies"At that time a Dutch colony, it seemed to him to be one of the few places where excavations could be crowned with success."

Find the missing link

Dubois' intense search for the missing link between apes and humans began two years after arriving in Sumatra; previously he was stationed in a military hospital and was only able to search for fossils during leisure time. However, he successfully applied for funds from the East India Committee for Scientific Research and was released from his work as a doctor. In addition, 50 convicts and two civil engineers were assigned to excavation work by the military. Dubois suspected that hominine fossils were most likely to be found in caves, but local helpers in Sumatra repeatedly misled him during his first excavation season in 1889 because they believed he wanted gold or saltpeter to be foundexplore. Therefore, he moved his fossil search to open areas on the island of Java. In his book The Early Period of man describes Friedemann Schrenk Dubois' approach as follows: "Obsessed with his idea, he began to dig at a site in Java, that would apply to today's ideas as completely hopeless. He dug in an area where within a radius of thousands of kilometers the slightest hint of remnants of a prehistoric man had never been found - and he dug in the right place to the centimeter. ”Dubois, however, knew tips from farmers who worked there Found animal fossils.

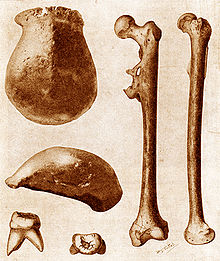

On the sandy banks of the Solo River near the village Trinil his aides hid in August 1891 a large molar and in October a skull cap with the distinctive features of a possible evolutionary linker : The skull bone was as thick as an ape and had a prominent supraorbital ridge , the resulting The size of the brain that can be deduced was too big for a monkey and too small for a human - it seemed to be the “primitive man” predicted by Ernst Haeckel. In August 1892, Dubois' workers finally discovered a fossil left femur , 15 meters from the first site , the characteristics of which suggested Dubois was able to walk upright.

Dubois initially assigned the tooth (whose assignment to the hominini is now considered uncertain) to an extinct great ape, called Anthropopithecus and has been known for some time from the Siwaliks in India . At the end of 1892, however, Dubois interpreted the roof of the skull and thighbones to mean that all three fossils were "an upright ape", according to the translation of the first scientific description of Anthropopithecus erectus Eug. Dubois . In December 1892 he received from Max Weber, a Dutch zoologist, sent the skull of a chimpanzee so that he could compare the top of its skull with that of a chimpanzee. Thereupon Dubois immediately changed the name of his finds and in future used the generic name of "primitive man" used by Haeckel, but kept the epithet erectus (from Latin erigere : "erect") - Pithecanthropus erectus ("upright ape man"). Today the fossils of the Java man are placed together with those of the Peking man and numerous other finds of Homo erectus , the three fossils of Dubois (archive number Trinil I to Trinil III) form the holotype of Homo erectus .

reception

In 1894 Dubois published his 50-page monograph entitled Pithecanthropus erectus: a human-like transitional form from Java , which is also a formal first description of the genus Pithecanthropus and its type species Pithecanthropus erectuscontains - and which he sent to numerous scholars in Europe. Their reactions were devastating: “Dubois and his monograph were openly mocked by colleagues, only a few [such as Ernst Haeckel] shared his conviction that he had found the missing link. Scholars doubted that the fossilized parts belonged together, doubted that they came from a single individual. ”In addition, when the workers found the fossils, they had not written down exact descriptions of the layers,“ which meant that [Dubois] was not aware of the importance of these Information could be. Dubois simply assumed it would be crazy to think that the three fossils were n'tcame from an individual; and his critics replied wickedly that it would be crazy to believe that they were. ” Rudolf Virchow , who in 1872 had misunderstood the Neanderthal as a pathologically altered specimen of an anatomically modern human being, interpreted the fossils as presumably coming from a giant gibbon and the thighbone than presumably modern.

Dubois returned to Europe in 1895 and got a job as a curator at the Imperial Museum of Natural History in Leiden , where he was responsible for the fossil collections from Indonesia and India. Through numerous lectures all over Europe and contacts with specialist colleagues, he tried to defend his view that he had found the missing link, but did not succeed, although he cited numerous other undoubtedly ancient fossils from the same find layer as evidence. Worse still, the German anatomist Gustav Schwalbe had obtained a plaster cast of the top of the skull and began lectures on Pithecanthropusand in 1899 he also published a 225-page monograph on the fossil, in which he came to the conclusion, “ Pithecanthropus occupies an intermediate position between Neanderthals and great apes . After this incident, Dubois disappeared from the anthropological scene for several decades. He stopped attending conferences, published nothing on the subject and for many years refused to show other researchers the Pithecanthropus fossils and the fauna associated with them. "

In the following years, Dubois dealt primarily with the relationship between brain size and body weight and was one of the first to recognize (although mathematically incorrectly calculated) that both are in an allometric relationship ( proportional to the body surface area ).

Honors

In 1891 he was the first descriptor of Dubois' antelope from the Pleistocene of Java, which was placed in the genus Duboisia named in his honor in 1911 .

In 1897 he was awarded an honorary doctorate in botany and zoology by the University of Amsterdam . He was there from 1898 to 1928 professor of mineralogy , geology and paleontology .

Fonts

- Eugène Dubois: Paleontological Investigation on Java. In: W. Eric Meikle, Sue Taylor Parker: Naming our Ancestors. An Anthology of Hominid Taxonomy. Waveland Press, Prospect Heights (Illinois) 1994, pp. 37-40, ISBN 0-88133-799-4 . - Translation of the first description of Anthropopithecus erectus (= Homo erectus ) written in Dutch in 1882 by the Berkeley Scientific Translation Service.

literature

- Bert Theunissen: Eugène Dubois and the Ape-Man from Java. The History of the First 'Missing Link' and Its Discoverer. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht / Boston 1988, ISBN 978-1-55608-081-4

- Pat Shipman: The Man Who Found the Missing Link. The Extraordinary Life of Eugene Dubois. Simon & Schuster, New York 2001, ISBN 978-0-29784290-3

- Pat Shipman and Paul Storm: Missing Left: Eugène Dubois and the Origins of Paleoanthropology. In: Evolutionary Anthropology. Volume 11, No. 3, 2002, pp. 108-116, full text

Web links

- Short biography on eugenedubois.org (Dutch)

- Biography of Eugène Dubois ( Memento of April 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Entry in Encyclopaedia Britannica

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ernst Haeckel: Natural history of creation. Common scientific lectures on the theory of evolution in general and that of Darwin, Goethe and Lamarck in particular, on the application of the same to the origin of man and other related fundamental questions of natural science. Georg Reimer, Berlin 1868, chapter 19 ( full text )

- ↑ Alan Walker and Pat Shipman: Turkana Boy. In search of the first person. Galila Verlag, Etsdorf am Kamp 2011, p. 52, ISBN 978-3-902533-77-7 .

- ↑ Friedemann Schrenk : The early days of man. The way to Homo sapiens. CH Beck, 1997, p. 81, ISBN 3-406-41059-6

- ^ The Discovery of Java Man in 1891 ( Memento June 4, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) From: Athena Review. Volume 4, No. 1: Homo erectus

- ↑ Gary J. Sawyer, Viktor Deak: The Long Way to Man. Life pictures from 7 million years of evolution. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2008, p. 121

- ↑ ancient Greek ἄνθρωπος ánthropos "man" and πίθηκος píthēkos "monkey"; Anthropopithecus troglodytes was the scientific name for chimpanzees at the time

- ^ Eugène Dubois: Paleontologische onderzoekingen op Java. Verslag van het Mijnwezen, 3rd quarter 1892, pp. 10-14

- ↑ Eugène Dubois: Pithecanthropus erectus: a human-like transitional form from Java. Landes-Druckerei, Batavia , 1894, full text

- ^ Eugène Dubois: On Pithecanthropus erectus: A Transitional Form between Man and the Apes. Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society, Ser. 2, 6, 1896, pp. 1-18

- ↑ Eugène Dubois: Pithecanthropus erectus, an ancestral form of humans. In: Anatomischer Anzeiger , Volume 12, 1896, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Alan Walker and Pat Shipman, Turkana Boy , p. 62

- ↑ Even today, some anatomists suspect that the thigh bone came from an anatomically modern person, see in particular Michael Herbert Day and Theya I. Molleson: The Trinil femora. In: MH Day (Ed.): Human Evolution. Symposia of the Society for the Study of Human Biology. Volume 11, Taylor & Francis, London 1973, pp. 127-154.

- ^ Alan Walker and Pat Shipman, Turkana Boy , p. 67

- ↑ Brain and nerve research. In: Salzburger Chronik für Stadt und Land / Salzburger Chronik / Salzburger Chronik. Tagblatt with the illustrated supplement “Die Woche im Bild” / Die Woche im Bild. Illustrated entertainment supplement to the “Salzburger Chronik” / Salzburger Chronik. Daily newspaper with the illustrated supplement “Oesterreichische / Österreichische Woche” / Österreichische Woche / Salzburger Zeitung. Tagblatt with the illustrated supplement “Austrian Week” / Salzburger Zeitung , January 30, 1934, p. 9 (online at ANNO ).

- ↑ Professor Dubois has died. In: Innsbrucker Nachrichten , December 20, 1940, p. 2 (online at ANNO ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dubois, Eugène |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dubois, Marie Eugène François Thomas |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Dutch physician, anatomist and anthropologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 28, 1858 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Eijsden , Netherlands |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 16, 1940 |

| Place of death | Haelen , Netherlands |