Farinelli

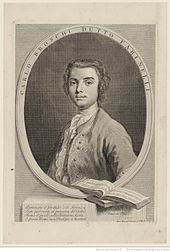

Farinelli (or Farinello ), actually Carlo Broschi , (born January 24, 1705 in Andria / Kingdom of Naples , † September 16, 1782 in Bologna ) was an Italian singer and the most famous of all castrati to this day .

Life

Origin and youth

Carlos parents, Salvatore Broschi (1680 or 1681-1717) and Caterina Barrese, both belonged to the lower nobility of southern Italy; Farinelli had two older siblings, Riccardo (* 1698) and Dorotea (* 1701). His father was an avid music lover, became governor of Maratea in 1706 and Cisternino for a short time in 1709 .

In order to get Carlos's beautiful singing voice, he was probably castrated around 1714 with the consent (or on request?) Of his father and then sent to Naples . There he was initially entrusted to the Farina family and studied singing at the Conservatorio Sant'Onofrio . Soon he became a private student of the composer Nicola Porpora , where he acquired an unusually virtuoso breathing and singing technique.

Carlo probably chose his stage name Farinelli in honor of the Farina family, in particular the Farina brothers, who were considered great connoisseurs and lovers of music and with whom he had often sung during his training at Porpora. Another theory is that Carlo may have been a nephew of the composer and violinist Farinelli, who was friends with Arcangelo Corelli .

Career in Italy and Vienna, 1720–1734

In 1720, the 15-year-old Farinelli entered the important Cappella del Tesoro di San Gennaro (in the cathedral of Naples ) as a soprano and had a first appearance during a private performance in the palace of the Prince of Torella in Naples in a supporting role as shepherd Tirsi in the pastoral Angelica e Medoro . The music for the latter came from his teacher Porpora and the libretto from Pietro Metastasio , with whom Farinelli would develop a lifelong friendship.

He experienced his early years on the opera stage mainly in Rome and Naples. Because women were not allowed to appear on the stages of the papal states and a corresponding tradition developed from this, the young Farinelli at the beginning of his career sang mainly female roles, namely in the Roman Teatro Alibert as Placidia in Porporas Flavio Anicio Olibrio (Rome, Carnival 1722 ), as Palmira in Cosroe by Carlo Francesco Pollarolo (Carnival 1722), as Sofonisba in Luca Antonio Predieri 's opera of the same name (Carnival 1722), as Adelaide in Porporas Adelaide (Carnival 1723) and as Salonice in Predieris Scipione (Carnival 1724).

In 1722 Farinelli is said to have appeared in Porpora's opera Eumene , but Barbier denies his participation in this opera. According to a well-known anecdote reported by Charles Burney and apparently from Farinelli himself, there was a competition in Rome during an aria with a solo trumpeter , Farinelli in holding and swelling and swelling ( messa di voce ) of a tone in astonishing ways Length and in continuous trills , and then with improvised "fastest and heaviest runs ". The audience was ecstatic with enthusiasm, and soon Carlo Broschi was known throughout southern Italy as il ragazzo (the boy).

Burney later claimed that Farinelli first performed in Vienna in 1724 (and a second time in 1728), but there is no evidence of this to date. Instead he was in Naples between 1724 and 1726 and sang at the Teatro San Bartolomeo alongside Vittoria Tesi and Anna Maria Strada del Po in various operas by the young Neapolitan composers Leonardo Vinci , Domenico Natale Sarro , and Leonardo Leo . Together with the Tesi, he also sang in an often-mentioned concert performance of Johann Adolph Hasse's Serenata Marc'Antonio e Cleopatra (Naples 1725), where the two performed with reversed roles, Farinelli as Cleopatra and the singer as Marc'Antonio, which he did not Realism, but baroque theater geared towards beauty was nothing unusual. Tesi also became a long-term friend, with whom he enjoyed working and whom he sometimes mentions in his letters.

With steadily increasing success, Farinelli performed in almost all major cities in Italy. He sang for the first time in Parma and Milan in 1726 and in Bologna in 1727. There, in a performance of Orlandini's Fedeltá coronata ossia l'Antigona, there was a spontaneous musical competition with the famous Antonio Bernacchi (born 1690) and Farinelli had to fight for the first time give up; between the two singers, however, there was no enmity, but a friendly respect. In Bologna, Farinelli also met Impresario Count Sicinio Pepoli, with whom he developed a long friendship.

Back in Rome he appeared for the first time in an opera by his brother Riccardo in 1728 : in his L'Isola d'Alcina . He was invited to Munich twice (autumn 1728 and 1729) to sing in works by Pietro Torri .

In the Carnival of 1728-29 Farinelli was then in Venice at the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo , where he sang in Leonardo Leo's Catone in Utica , Porporas Semiramide riconosciuta and Ezio , and in Antonio Pollarolo's L'Abbandono di Armida . He was now so famous that he made a fortune with his sensational performances. He returned the following year and entered a. in the world premiere of his brother Riccardo's opera Idaspe , who served the audience's greed for sensation in the bravura arie Son qual guerriero in campo armato and unreservedly showcased Carlos's virtuoso qualities and huge vocal range (g to c '' '). The aria became one of Farinelli's draft horses.

After appearances in Turin , Milan and Ferrara, he made a detour to Vienna in 1732 . The imperial family, whom he delighted with his singing in numerous private concerts, received him in a particularly friendly and benevolent manner. He was named the imperial “Court and Chamber Musicus” and, in addition to countless precious gifts, he received an annual pension of 1,000 guilders thanks to Empress Elisabeth Christine . On one occasion, Emperor Charles VI said . who was a great music connoisseur and lover that "in his singing ... everything is supernatural," but he also made a well-intentioned criticism:

“Those gigantic steps ..., those infinite notes and gargeleyes ( ces notes qui finissent jamais ) surprise us, and now it is time for them to please; they are too lavish on the goods nature has given them; if you want to capture the heart, you have to go a level, simple path. "

Farinelli took this advice to heart and as a result he changed his singing style and "mixed the lively with the pathetic , the simple with the sublime, and in this way he moved every listener as well as astonishing them". He was encouraged in this, among other things, by his friend Metastasio, who was meanwhile the imperial court poet.

On October 29, 1732, he officially became a citizen of Bologna, where he intended to settle later. A performance of Hasse's Siroe re di Persia at the Teatro Malvezzi in Bologna in May 1733, where Farinelli sang Caffarelli , Vittoria Tesi and Anna Maria Peruzzi alongside his younger colleague (and rival) is considered an operatic highlight .

Towards the end of his Italian career, Farinelli spent the carnival seasons of 1733 and 1734 again in Venice and appeared in Giacomelli's Adriano in Siria (1733) and Merope (1734). One of his most famous and sublime show pieces comes from the latter opera, the aria " Quell'usignolo ch'é innamorato ", with which he later shone in London and Spain.

Farinelli had his very last appearance in Italy at the beginning of September 1734 at the Teatro della Pergola in Florence (alongside Vittoria Tesi and Caterina Fumagalli), in Orlandini's L'innocenza giustificata .

London and Paris, 1734–1737

In the autumn of 1734 Farinelli traveled to London to support the influential party of the opponents of Handel , who had founded the rival Opera of the Nobility with Porpora as musical director and Senesino as first singer and Cuzzoni as prima donna . His first appearance at the Lincoln's Inn Fields theater was in the opera Artaserse von Hasse (with interludes by Nicola Porpora and Carlos's brother Riccardo Broschi ), with triumphant success. It is said that when they first appeared together, Senesino was so moved by Farinelli's singing that he forgot his own role and hugged his younger colleague on stage. The Prince of Wales and the court showered him with goodwill and gifts.

“You loved the others, you worshiped them. It's just gorgeous. Impossible to sing better. A magic draws the masses to him. Imagine all the talent of Senesino and Carestinis in a voice that is more beautiful than the two together. "

In just under three years until June 1737, Farinelli et al. a. Appearances in Porpora's operas Polifemo and Mitridate , in Adriano and La clemenza di Tito by Veracini , Siroe re di Persia by Hasse, Onorio by Campi, Demofoonte by Duni and in Riccardo Broschi's Merope . The Opera of the Nobility was so bold as to perform Handel's own opera Ottone in December 1734 , with Farinelli as Adelberto and z. Some with arias from other works by Handel. There was also an encounter between the singer and the German composer at a party of Lady Rich, who at the request of the guests performed an aria on the harpsichord. When Farinelli was asked to sing (out of naivety or malice?), However, he saw through the embarrassing potential of the situation and had the tact and decency to refuse.

Even Farinelli's wonderful singing was unable to make Italian opera in England a long-term success. After Porpora had returned to Italy together with Cuzzoni and Senesino in 1736, Farinelli also left relatively suddenly in June 1737 after several frustrating experiences with the English public and critics and followed a call to the Spanish court. On the way he spent a few months in anti-neuter France , where he was before Louis XV. sang.

Madrid, 1737-1760

In Spain, which he had originally only wanted to visit for five months, he finally stayed for almost twenty-five years (1737–1759). His singing was used by Queen Elisabetta Farnese to cure Philip V's severe depression , just as the famous soprano Matteuccio had done for Charles II 40 years earlier . For nine years (until Philip's death in 1746) Farinelli was only allowed to sing for the king - this retreat from a public opera career at the age of only 32 contributed to his myth. According to a letter from Farinelli dated February 15, 1738 to his friend Count Pepoli, he “had to perform eight or nine arias every evening. There is never a break ”. Later Burney wrote with reference to Farinelli's own statement that there were always the same have been four arias, including hatred " Per questo dolce amplesso " and " Pallido il Sole " from hatred Artaserse and a Menuet (perhaps Fortunate passate mie pene of Attilio Ariosti ) "Which he used to change as he pleased", thus provided with so-called arbitrary decorations . Thus Farinelli gained influence over the king, who gave him the power - if not the office - of prime minister. The singer was clever and humble enough to use this power only discreetly, especially since he apparently had no particular interest in politics.

Under Ferdinand VI. from 1746 he had a similar position and got on particularly well with the highly musical Queen Maria Barbara de Bragança , who appointed him head of the Italian opera. In this role Farinelli invited the most important singers in Italy to Madrid, such as the castrati Caffarelli (1739), Giovanni Manzuoli and Gizziello , the singers Vittoria Tesi (1739), Anna Peruzzi and Regina Mingotti , and the tenor Anton Raaff . A special friendship - maybe even ( platonic ?) Love - connected him with the young singer Teresa Castellini , who stayed in Spain from 1748 to 1758 (with a short interruption), and with whom he met Amigoni in a fictional group portrait together with his Pen pal metastasio painted (see picture).

Farinelli was awarded the Calatrava Cross for his services in 1750 . When Charles III. of Spain ascended the throne in 1759, he had to leave Spain because the new king had no interest in music and a personal dislike for him, and also wanted to save money. Despite this, the singer received a lifelong pension.

Retirement

Farinelli retired with his fortune in Bologna and spent the rest of his days with his memories. He had at least one harpsichord and one pianoforte that Queen Maria Barbara had bequeathed to him after her death. He gave them the names of the famous painters Correggio and Raffaello and played Charles Burney during his visit in 1770.

Farinelli did not live alone in his Bolognese house, but had taken in Matteo, a son of his sister, who stayed with his uncle even after his marriage (and despite quarrels with his wife); the young couple's children sweetened the singer's age. Farinelli's friends included the famous counterpoint teacher Padre Martini and the children of his late friend Count Pepoli.

He received and received numerous visits from musicians and music lovers, including from 1763 (several times) from Gluck . There were also young castrati who adored him and hoped for tips from him. Emperor Joseph II came in 1769, Charles Burney and Leopold and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1770 . An anecdote reported by Casanova claims that in 1772, after Farinelli sang an aria to her on the harpsichord, the Electress of Saxony fell into his arms and exclaimed: “Now I can die happily! ".

Farinelli fell ill with a fever in September 1782 and died on September 16. At his request, he was buried in the mantle of the Calatrava Order after 50 of the poorest people in Bologna had led his coffin to the Capuchin Church with candles in hand; afterwards each of the poor got a coin.

Voice and art

Farinelli has gone down in history as perhaps the greatest vocal and singing miracle that has ever lived. In what was already a “golden age of bel canto ”, he was praised more than any other singer by contemporaries, and his qualities were often perceived as “supernatural” (including by Charles VI; see also the quote from Burney (below)). Not only must he have had a voice of extraordinary beauty, sweetness and power, which Quantz described as “penetrating, full, thick, light and even soprano voice”; he also had an unusually large vocal range, which (again according to Quantz):

“... at that time (1725) extended from the unprimed a to the three-slashed d; A few years later, however, it has increased in depth with single notes, but without losing the high notes: in such a way that in many operas an aria, mostly an adagio , in the range of the contralt , and the others in the range of the soprano were written. His intonation was pure, his trillo beautiful, his chest extraordinarily strong in holding his breath, and his throat very familiar; so that he brought out the most remote intervals , swiftly, and with the greatest ease and certainty. Broken passages (= broken chords ) made him, like all other runs, no trouble at all. In the arbitrary decorations of the Adagio he was very fruitful. the fire of youth, his great talent, the general approval, and the finished throat, made him treat it too lavishly now and then. His figure was beneficial for the theater: the action (= his acting), however, was not very close to his heart. "

Farinelli's completely perfect breathing technique, as she u. a. was vividly described in the anecdote of the competition with a trumpeter mentioned above (see above). This breathing technique was the most important basis for his amazing virtuosity. Some arias composed for him, such as For example, Riccardo Broschi's “ Son qual nave ch'agitata ”, Veracini's “ Amor dover rispetto ” or Giacomelli's “ Quell usignolo ” and the cadences that Farinelli himself invented are proof of his ability to (apparently) breathe incredibly long phrases to sing. He combined all of this with great musical creativity and expressiveness.

“... he surpassed all singers so much ... But he was not only superior to them in terms of speed, but he combined all great singers excellence in himself. Regarding his voice: strength, comfort and wide range; in his way of singing: tenderness, grace and skill. He had the advantages of not being met with anyone before or after him; Advantages, the power of which one could not withstand and which had to defeat every listener, the connoisseur and the ignorant, friends and enemies. "

Roles for Farinelli

The following is a list of roles that were composed specifically for Carlo Broschi called Farinelli . His most important fellow singers are also named.

- Clisauro in L'Andromeda by Domenico Natale Sarro ; Premiere: January 28, 1721, Naples ; with Marianna Benti Bulgarelli (" La Romanina ") a. a.

- Palmira in Cosroe by Carlo Francesco Pollarolo , WP: Carnival 1722, Rome , Teatro Alibert; with Domenico Gizzi a. a.

- Title role in Sofonisba by Luca Antonio Predieri ; WP: Carnival 1722, Rome, Teatro Alibert; with Giovanni Carestini , Domenico Gizzi a. a.

- Title role in Adelaide by Nicola Porpora ; WP: Carnival 1723, Rome, Teatro Alibert; with Domenico Gizzi a. a.

- Tirinto in Imeneo by Nicola Porpora; WP: 1723 in Naples; with Antonia Merighi , Marianna Benti Bulgarelli (“ La Romanina ”) a. a.

- Salonice in Scipione by Luca Antonio Predieri; WP: Carnival 1724, Rome, Teatro Alibert; u. a. with Domenico Gizzi

- Titiro in the favola pastoral La Tigrena by Francesco Gasparini ; Premiere on January 2, 1724 in Rome, Palazzo Cesarini ... De Mello de Castro; u. a. with Farfallino

- Berenice in Farnace (1st version) by Leonardo Vinci ; Premiere: January 8th 1724, Rome, Teatro Alibert; with Domenico Gizzi, Filippo Finazzi a . a.

- Nino in Semiramide, regina dell'Assiria by Nicola Porpora; Premiere: Spring 1724, Naples, Teatro San Bartolomeo; with Anna Maria Strada , Diana Vico a . a.

- Damiro in Eraclea by Leonardo Vinci ; Premiere: October 1st, 1724, Naples, Teatro San Bartolomeo ; with Vittoria Tesi , Anna Maria Strada, Diana Vico u. a.

- Rosanno in Tito Sempronio Gracco by Domenico Natale Sarro ; WP: Carnival 1725, Naples, Teatro San Bartolomeo; with Vittoria Tesi, Anna Maria Strada, Diana Vico u. a.

- Decio in Zenobia in Palmira by Leonardo Leo ; Premiere: May 13th 1725, Naples, Teatro San Bartolomeo; with Vittoria Tesi, Anna Maria Strada, Diana Vico u. a.

- Aristeo in Amore e fortuna by Giovanni Porta ; Premiere: October 1, 1725, Naples, Teatro San Bartolomeo; with Vittoria Tesi, Anna Maria Strada, Diana Vico u. a

- Oreste in Astianatte by Leonardo Vinci; Premiere: December 2nd, 1725, Naples, Teatro San Bartolomeo; with Vittoria Tesi, Anna Maria Strada, Diana Vico u. a.

- Ernando in La Lucinda fedele by Giovanni Porta; WP: Carnival 1726, Naples, Teatro San Bartolomeo; with Vittoria Tesi, Anna Maria Strada, Diana Vico u. a.

- Niccomede in I fratelli riconosciuti by Giovanni Maria Capelli ; WP: Spring 1726, Parma , Teatro Ducale; with Giovanni Carestini , Diana Vico, Lucia Facchinelli a . a.

- Aldano in L'amor generoso by Giovanni Battista Costanzi ; Premiere: January 7th 1727, Rome, Teatro Capranica

- Rodrigo in Il Cid by Leonardo Leo; Premiere: February 10, 1727, Rome, Teatro Capranica

- Tolomeo in Cesare in Egitto by Luca Antonio Predieri; WP: Carnival 1728, Rome, Teatro Capranica

- Ruggiero in L'isola d'Alcina by Riccardo Broschi ; WP: Carnival 1728, Rome, Teatro Capranica

- Giasone in Medo by Leonardo Vinci; WP: Spring 1728, Parma, Teatro Ducale; u. a. with Vittoria Tesi and Antonio Bernacchi

- Title role in Nicomede by Pietro Torri ; Premiere: October 1728, Munich , Hoftheater; u. a. with Elisabetta Casolani

- Arbace in Catone in Utica by Leonardo Leo; Premiere: December 26th 1728, Venice , Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo ; with Nicola Grimaldi (Nicolino), Domenico Gizzi, Lucia Facchinelli a. a.

- Mirteo in Semiramide riconosciuta by Nicola Porpora; Premiere: February 12th 1729, Venice, Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo; u. a. with Nicola Grimaldi (Nicolino)

- Quinto Fabio in Lucio Papirio dittatore by Geminiano Giacomelli ; WP: Spring 1729, Parma, Nuovo Ducal Teatro; with Faustina Bordoni , Antonio Bernacchi, Francesco Borosini a . a.

- Title role in Edipo by Pietro Torri; Premiere: October 22nd, 1729 in Munich; with Faustina Bordoni, Elisabetta Casolani

- Arbace in Artaserse by Johann Adolph Hasse ; Premiere: February 11, 1730, Venice, Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo; with Francesca Cuzzoni , Nicola Grimaldi (Nicolino), Filippo Giorgi u. a.

- Title role in Poro by Nicola Porpora; WP: Carnival 1731, Turin , Regio Teatro; with Faustina Bordoni, Anna Girò , Angelo Amorevoli u. a.

- Dario in Idaspe by Riccardo Broschi; Premiere: January 25th 1730, Venice, Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo; with Francesca Cuzzoni, Nicola Grimaldi (Nicolino), Filippo Giorgi u. a.

- Publio Cornelio Scipione in Scipione in Cartagine nuova by Geminiano Giacomelli; WP: Spring 1730, Piacenza , Teatro Ducale; u. a. with Francesca Cuzzoni and Giovanni Carestini

- Title role in Ezio by Riccardo Broschi; WP: Carnival 1731, Turin, Regio Teatro; with Faustina Bordoni, Anna Girò, Angelo Amorevoli u. a.

- Merione in Farnace by Giovanni Porta; WP: Spring 1731, Bologna , Teatro Malvezzi; with Francesca Cuzzoni, Vittoria Tesi, Antonio Bernacchi a. a.

- Teseo in Arianna e Teseo by Riccardo Broschi; Premiere: August 28, 1731, Milan , Regio Ducal Teatro; u. a. with Vittoria Tesi as Arianna

- Arbace in Catone in Utica by Johann Adolph Hasse; Premiere: December 26th 1731, Turin, Regio Teatro; u. a. with Vittoria Tesi, Filippo Giorgi

- Epitide in Merope by Riccardo Broschi; WP: Carnival 1732, Turin, Regio Teatro; with Vittoria Tesi, Filippo Giorgi u. a.

- Farnaspe in Adriano in Siria by Geminiano Giacomelli; Premiere: January 30th 1733, Venice, Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo; with Antonia Merighi, Filippo Giorgi u. a.

- Title role in Siroe, re di Persia by Johann Adolph Hasse; Premiere: May 2nd, 1733, Bologna, Teatro Malvezzi; with Caffarelli , Vittoria Tesi, Anna Peruzzi , Filippo Giorgi, etc. a

- Demetrio in Berenice by Francesco Araja ; Premiere: December 26th 1733, Venice, Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo; u. a. with Lucia Facchinelli and Caffarelli

- Epitide in Merope by Geminiano Giacomelli; Premiere: February 20, 1734, Venice, Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo; with Caffarelli, Lucia Facchinelli a. a.

- Aci in Polifemo by Nicola Porpora; WP: February 1, 1735, London , King's Theater in the Haymarket; u. a. with Francesca Cuzzoni, Senesino and the bassist Antonio Montagnana

- Achille in Ifigenia in Aulide by Nicola Porpora; Premiere: May 3, 1735, London, King's Theater in the Haymarket; u. a. with Francesca Cuzzoni, Senesino (Francesco Bernardi) and Montagnana

- Farnaspe in Adriano in Siria by Francesco Maria Veracini ; Premiere: November 25th 1735, London, King's Theater in the Haymarket; u. a. with Francesca Cuzzoni, Senesino (Francesco Bernardi) and Montagnana

- Sifare in Mitridate (2nd version) by Nicola Porpora; Premiere: January 24th 1736, London, King's Theater in the Haymarket; u. a. with Francesca Cuzzoni, Senesino (Francesco Bernardi) and Montagnana

- Alceste in Demetrio by Giovanni Battista Pescetti ; Premiere: February 12, 1737, London, King's Theater in the Haymarket; with Antonia Merighi, Élisabeth Duparc (" La Francesina "), Montagnana a. a.

- Sesto in La clemenza di Tito by Francesco Maria Veracini; WP: April 12, 1737, London, King's Theater in the Haymarket; with Antonia Merighi, Élisabeth Duparc (" La Francesina "), Antonio Montagnana a. a.

- Timante in Demofoonte by Egidio Romualdo Duni ; Premiere: May 24th 1737, London, King's Theater in the Haymarket; with Antonia Merighi, Élisabeth Duparc (" La Francesina "), Maria A. Marchesini a . a.

- Nice in La danza by Nicolò Conforti ; Premiere: 1756 in Madrid ; with Gioacchino Conti ( Gizziello )

exhumation

In 1998 the Farinelli Study Center opened its doors in Bologna, dedicated to the historical memory of the famous castrato who lived in Bologna from 1761 to 1782 and died there. The centre's core projects include the restoration of Farinelli's tomb in the Certosa of Bologna (2000) and the opening of Farinelli's tomb (2006). The opening of the tomb was made possible by the Florentine antiques dealer Alberto Bruschi and Luigi Verdi, Secretary of the Farinelli Study Center. The anthropologist Maria Giovanna Belcastro from the University of Bologna, the paleoanthropologist Gino Fornaciari from the University of Pisa and the engineer David Howard from the University of York were the scientists responsible for the analysis of Farinelli's remains. The exhumation Farinelli was held on July 12 of 2006. The aim of the excavations was to gain knowledge about possible illnesses or malformations of the singer and possibly also about his extraordinary voice. Only a few bone remains were found in a relatively poor state of preservation, which provided information about his health or illnesses, but not about his voice. The main results were:

- Farinelli had excessively long limbs and was believed to be six feet tall, which was well above average in his day, especially in southern Europe. Both are almost certainly a result of castration.

- His bones showed advanced osteoporosis , which in this form would be more typical of older women in the postmenopause .

- He had hyperostosis frontalis interna (HPI), that is, a partial thickening of the inner frontal bone. This symptom also occurs mainly in older women and is probably also a consequence of the androgen deficiency caused by castration in Farinelli . As far as we know from contemporary reports, the singer does not seem to have necessarily suffered from other side effects of this disease ( headache , feelings of inferiority, etc.).

- His teeth were relatively good for his age (almost 78) and it is believed that he already used toothbrushes for grooming.

posterity

Farinelli's life was processed in numerous operas. Starting with a work by John Barnett, performed in London in 1839 based on the anonymous Parisian model Farinelli, ou le Bouffe du Roi (... or the king's buffo ) to Auber's La part du diable (The Devil's Share, 1843) to contemporary composers such as Matteo d'Amicos (* 1955) Farinelli, la voce perduta (… the lost voice ) and Siegfried Matthus ' Farinelli, or the power of song .

Farinelli's life was also processed in operettas - e. B. Hermann Zumpes operetta Farinelli based on a model by Friedrich Wilhelm Wulff .

In 1964 the Farinelli primary school was founded in Schwabing .

In 1994 the Belgian director Gérard Corbiau made the film Farinelli, the castrato with Stefano Dionisi in the title role. The location of the film was u. a. the margravial opera house in Bayreuth. For the soundtrack using modern computer technology from the voices of the US was countertenor Derek Lee Ragin and Polish coloratura soprano Ewa Malas-Godlewska an artificial "Farinelli-voice" created. The film was awarded the Golden Globe for "best non-English language film" and was also nominated for an Oscar in this category.

Discography

Farinelli's extraordinary vocal and singing talent, the extreme perfection and beauty of his voice and singing in every respect have faded away forever. However, there are some CDs that give a certain impression of his repertoire and his abilities.

- Vivica Exactly : Arias for Farinelli . Academy for Early Music Berlin , René Jacobs . Harmonia mundi HMC 801778, 2002/2003.

- Ann Hallenberg : Farinelli - A portrait, live in Bergen . Les Talents lyriques, Christophe Rousset , Aparte (harmonia mundi), 2011/2016.

- Philippe Jaroussky : Arias for Farinelli by Porpora . Venice Baroque Orchestra, Andrea Marcon, Warner, 2013.

literature

- Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. Le castrat des Lumières. Grasset, Paris 1995, ISBN 2-246-48401-4 (German edition: Farinelli. The castrato of the kings. The biography. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, ISBN 3-430-11176-5 ).

- Charles Burney : Diary of a Musical Journey (translated from CD Ebeling), Hamburg 1772–73, new facsimile edition by Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003.

- Sandro Cappelletto: La voce perduta. Vita di Farinelli, evirato cantore (= Biblioteca di cultura musicale. Improvvisi 9). EDT, Turin 1995, ISBN 88-7063-223-7 .

- Johanna Dombois: Farinelli's skinned voice. Voice design as a cultural technique. In: Music & Aesthetics. Issue 51 = 13th year, issue 3, 2009, ISSN 1432-9425 , pp. 54-72.

- Hubert Ortkemper: Angels against their will. The world of the castrati. Henschel, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-89487-006-0 .

- Reinhard Strohm: "Who is Farinelli?" and René Jacobs : "There are no more castrati, what now?", booklet accompanying the CD: Arias for Farinelli . Vivicagenaux , Academy for Early Music Berlin, R. Jacobs, published by: Harmonia mundi (2002/2003, HMC 801778), pp. 38–44.

- Angelika Tasler: Carlo Broschi (Farinelli). In: Jürgen Wurst, Alexander Langheiter (Ed.): Monachia. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-88645-156-9 , p. 78 ff.

Fiction

- Marc David: Farinelli. Memoires d'un castra. Récit. Perrin, Paris 1994, ISBN 2-262-01086-2 (German edition: Farinelli. Roman. Limes, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-8090-2404-X ).

- Franzpeter Messmer: The Venusman. Fretz & Wasmuth, Bern / Munich / Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-502-11905-8 .

Web links

- Performances with Carlo Broschi (Farinelli) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- Literature by and about Farinelli in the catalog of the German National Library

- long article in Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1900) in Wikisource (English only)

- Farinelli: il castrato in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Thomas Schmoll: Arias of the castrato Farinelli: Music for the depressed king. On: spiegel.de of October 7, 2019; accessed on October 18, 2019.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 21 f.

- ↑ a b c Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. Le castrat des Lumières. Paris 1995.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 22.

- ↑ Christian von Deuster: How did the castrati sing? Historical considerations. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 25, 2006, p. 140.

-

↑ Christian von Deuster: How did the castrati sing? Historical considerations. 2006;

Hubert Ortkemper: Angels against their will. The world of the castrati. Berlin 1993;

Reinhard Strohm: Who is Farinelli? In the booklet accompanying the CD “Arias for Farinelli”. Vivicagenaux, Harmonia mundi (2002/2003). - ↑ In the literature (among others von Barbier: Farinelli. Der Kastrat der Könige. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 33) it is claimed again and again that Carlo could not call himself Porporino because he was not Porpora's first pupil and was before him Antonio Uberti (1719–1783) was supposedly the first pupil of Porporas to choose this name. However, since Uberti was only born in 1719, Farinelli cannot have taken his name into account. Apart from that, many famous castrati had a stage name that had nothing to do with their teacher, such as B. Domenico Cecchi called “il Cortona” (1650–1718), Siface (1653–1697), Matteuccio (1667–1737), Nicola Grimaldi called “Nicolino” (1673–1732), or Senesino (1686–1758).

- ↑ He gave up this church position in 1723. Juliane Riepe: Singer in the Church, On Practice in Italian Music Centers of the 18th Century . Online at Academia , p. 67.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. (Portuguese version; title of the French original: Histoire des Castrats. ), Lisbon 1991 (originally Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, Paris, 1989), p. 104.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. (Portuguese version; title of the French original: Histoire des Castrats. ), Lisbon 1991 (originally Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, Paris, 1989), p. 104.

- ^ Flavio Anicio Olibrio (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Cosroe (Carlo Francesco Pollarolo) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Sofonisba (Luca Antonio Predieri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Adelaide (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Scipione (Luca Antonio Predieri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 37.

- ^ Charles Burney: Diary of a musical journey (translated from CD Ebeling), Hamburg 1772-73, new facsimile edition by Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003. Vol. I: through France and Italy , column 153.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 52.

- ^ Eraclea (Leonardo Vinci) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Astianatte (Leonardo Vinci) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Tito Sempronio Gracco (Domenico Natale Sarro) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Zenobia in Palmira (Leonardo Leo) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ↑ Raffaele Mellace: Johann Adolf Hasse , L'Epos, 2004, pp. 39–40 (Italian).

- ↑ Michael Lorenz: The Will of Vittoria Tesi Tramontini , March 31, 2016 (update: July 30, 2018), on: Michael Lorenz - Musical Trifles and Biographical Paralipomena , online (accessed October 23, 2019).

- ↑ Raffaele Mellace: Johann Adolf Hasse , L'Epos, 2004, p 197 (Italian).

- ↑ Reinhard Strohm: “Who is Farinelli?”, Booklet text for the CD: Arias for Farinelli , with Vivicagenaux , Academy for Early Music Berlin, René Jacobs ; harmonia mundi, 2002-2003. Pp. 38–44, here: 41.

- ^ Adriana De Feo: "Johann Adolf Hasse's Marc'Antonio e Cleopatra ", on the website of the Mozart Opera Institute of the Mozarteum University Salzburg, on Mozartoper.at (accessed on October 22, 2019).

- ↑ Patrick Barbier : Farinelli, the castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf, 1995, pp. 37, 47f, 50f, 62, 65, 73, 141, 167.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier : Farinelli, the castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf, 1995, p. 40 ff.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 40 f.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 41.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 42.

- ↑ In Nicomede (premiere: October 1728; Nicomede (Pietro Torri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna ) and in Edipo (premiere: October 22, 1729, Edipo (Pietro Torri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna ).

- ↑ Barbier mentions these trips only in passing and speaks of 1727. Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 43.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli à Venise. In: La Venise de Vivaldi. Editions Grasset, Paris 2002, pp. 200–209, here: 200 & 202.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 44.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli à Venise. In: La Venise de Vivaldi. Editions Grasset, Paris 2002, pp. 200–209, here: pp. 202–203.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, pp. 46-51.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 58.

- ^ A b Charles Burney: Diary of a Musical Journey (translated from CD Ebeling), Hamburg 1772-73, new facsimile edition by Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003. Volume I: through France and Italy. Column 154.

- ^ Charles Burney: Diary of a Musical Journey. (translated by CD Ebeling), Hamburg 1772-73, new facsimile edition by Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003. Volume I: through France and Italy. Column 154-155.

- ^ Charles Burney: Diary of a Musical Journey. (translated by CD Ebeling), Hamburg 1772-73. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003. Volume I: through France and Italy. Column 155.

- ↑ Raffaele Mellace: Johann Adolf Hasse. L'Epos, 2004, pp. 106-107 (Italian).

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, pp. 62 and 64.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 67 f.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli à Venise. In: La Venise de Vivaldi. Editions Grasset, Paris 2002, pp. 200–209, here: 203 f.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 73.

- ↑ The opera was a bit older, so it was not a world premiere: L'innocenza giustificata (Giuseppe Maria Orlandini) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna . Farinelli sang for the first time in London at the end of October.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 96.

- ↑ Reinhard Strohm: "Who is Farinelli?", Booklet text for the CD: Arias for Farinelli . Vivicagenaux , Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, R. Jacobs, published by: Harmonia mundi (2002/2003, HMC 801778), pp. 38–44, here: 43.

- ↑ Burney specifically writes that Farinelli himself confirmed this story to be true. Charles Burney: Diary of a Musical Journey. (translated by CD Ebeling), Hamburg 1772-73. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003. Volume I: through France and Italy. Column 162.

- ^ Abbé Prévost: Le Pour et le Contre. Volume VI, p. 103 f. Quoted here from Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 85.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, pp. 96-103.

- ↑ So without Handel's consent or participation

- ^ Ottone, re di Germania (Georg Friedrich Händel) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 93.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, pp. 97 & 101.

- ↑ Every day eight or nine arias are in fact considerably more than in a normal baroque opera career, where a primo uomo only had to sing about five arias per opera (with pauses and recitatives in between), and between the individual performances again and again for days or weeks of rest.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 124.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 118.

- ^ Charles Burney: Diary of a Musical Journey. (translated by CD Ebeling), Hamburg 1772-73. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003. Volume I: through France and Italy. Column 156 f.

- ↑ It is often claimed in other literature that Farinelli should have sung the same four or five arias every evening. In addition: Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 118 f. and 124.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, 1995, p. 160 ff.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, 1995, p. 159 f.

- ^ Charles Burney: Diary of a Musical Journey. Hamburg 1772 (translated by CD Ebeling), p. 151 f.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, pp. 210-212.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 213.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 214 f.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 217 f.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 220.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli. The castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 226.

- ^ Rodolfo Celletti: History of Belcanto. (German translation), Bärenreiter, Kassel, 1989, p. 73.

- ^ Johann Joachim Quantz: Mr. Johann Joachim Quantzens curriculum vitae. In: Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg: Historically critical contributions to the recording of the music. Pp. 197-250, here: p. 233, on Wikimedia (accessed November 29, 2019).

- ↑ Note d. Author

- ↑ These are free adornments by playing around, among other things, i.e. not the cadence trills at the end of a phrase, which are considered mandatory (but which are not performed by all singers nowadays, often not even by stars of the baroque music scene). (Editor's note) .

- ↑ Note d. Author

- ^ Johann Joachim Quantz: Mr. Johann Joachim Quantzens curriculum vitae. In: Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg: Historically critical contributions to the recording of the music. Pp. 197-250, here: pp. 233-234, on Wikimedia (accessed November 29, 2019).

- ↑ An interpretation of this aria can be heard on the CD: Vivicagenaux : Arias for Farinelli. Academy for Early Music Berlin , René Jacobs . Harmonia mundi HMC 801778, 2002/2003.

- ^ Charles Burney: Diary of a Musical Journey. (translated by CD Ebeling), Hamburg 1772-73, new facsimile edition by Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003. Volume I: through France and Italy. Columns 155-156.

- ^ L 'Andromeda (Domenico Natale Sarro) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Cosroe (Carlo Francesco Pollarolo) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Sofonisba (Luca Antonio Predieri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Adelaide (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Imeneo (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Scipione (Luca Antonio Predieri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ↑ La Tigrena (Francesco Gasparini) in Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Farnace (Leonardo Vinci) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- ^ Semiramide, regina dell'Assiria (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Eraclea (Leonardo Vinci) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Tito Sempronio Gracco (Domenico Natale Sarro) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Zenobia in Palmira (Leonardo Leo) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Amore e fortuna (Giovanni Porta) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Astianatte (Leonardo Vinci) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ La Lucinda fedele (Giovanni Porta) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ I fratelli riconosciuti (Giovanni Maria Capelli) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ L 'amor generoso (Giovanni Battista Costanzi) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Il Cid (Leonardo Leo) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Cesare in Egitto (Luca Antonio Predieri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ L'isola d'Alcina (Riccardo Broschi) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Medo (Leonardo Vinci) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Nicomede (Pietro Torri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Catone in Utica (Leonardo Leo) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Semiramide riconosciuta (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Lucio Papirio dittatore (Geminiano Giacomelli) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Edipo (Pietro Torri) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Artaserse (Johann Adolf Hasse) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Poro (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Idaspe (Riccardo Broschi) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Scipione in Cartagine nuova (Geminiano Giacomelli) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Ezio (Riccardo Broschi) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Farnace (Giovanni Porta) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Arianna e Teseo (Riccardo Broschi) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Catone in Utica (Johann Adolf Hasse) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Merope (Riccardo Broschi) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Adriano in Siria (Geminiano Giacomelli) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Siroe, re di Persia (Johann Adolf Hasse) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Berenice (Francesco Araia) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Merope (Geminiano Giacomelli) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Polifemo (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ↑ Ifigenia in Aulide (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Adriano in Siria (Francesco Maria Veracini) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Mitridate (Nicola Porpora) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Demetrio (Giovanni Battista Pescetti) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ La clemenza di Tito (Francesco Maria Veracini) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Demofoonte (Egidio Romualdo Duni) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ La danza (Nicolò Conforti) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna .

- ^ Maria Giovanna Belcastro, Antonio Todero, Gino Fornaciari, Valentina Mariott: Hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI) and castration: The case of the famous singer Farinelli (1705-1782). In: Journal of anatomy. Volume 219, number 5, November 2011, pp. 632-637, doi : 10.1111 / j.1469-7580.2011.01413.x , PMID 21740437 , PMC 3222842 (free full text).

- ↑ Kristina Killgrove: Castration Affected Skeleton Of Famous Opera Singer Farinelli, Archaeologists Say , June 1, 2015, summary of the results of the exhumation at Forbes / Science (English; last accessed October 4, 2019).

- ^ MG Belcastro, Valentina Mariotti, B. Bonfiglioli, A. Todero, G. Bocchini, M. Bettuzzi, R. Brancaccio, S. De Stefano, F. Casali, MP Morigi: Dental status and 3D reconstruction of the malocclusion of the famous singer Farinelli (1705-1782). In: International Journal of Paleopathology . December 2014.

- ↑ Farinelli. Operetta by Hermann Zumpe in the German Digital Library

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Farinelli |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Broschi, Carlo (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian castrato |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 24, 1705 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Andria |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 16, 1782 |

| Place of death | Bologna |