Mrs. Jenny Treibel

Frau Jenny Treibel or “Where the heart finds itself” is a novel by Theodor Fontane . Pre-printed in the Deutsche Rundschau from January to April 1892, and delivered as a book at the end of 1892 (with the year 1893), the novel quickly won the favor of the public and critics, which it has retained to this day without any noticeable restriction. Half ironically , the reader is told a story along the lines of a comedy . It's about property and the social standing associated with it, about education versus property, about poetry, real and false feelings.

content

At the center of the novel are two families from Berlin: On the one hand, the upper-class Treibels - the Berliner Blau factory owner and councilor Treibel, his wife Jenny (née Bürstenbinder) and sons Otto and Leopold, and on the other hand, high school professor Wilibald Schmidt and his daughter Corinna, who represent the educated middle class. The connection between the families originated in Wilibald and Jenny's youth. At that time they both lived in Berlin's Adlerstrasse, Wilibald with his parents on the first floor of a “handsome, but otherwise old-fashioned house” (chap. 1), Jenny Bürstenbinder in the house opposite where her father had a shop for “material- and colonial goods ”(Chapter 8). As a student, Wilibald was in love with Jenny and wrote her love poems, including the song with the “famous passage 'Where hearts are found'” (Chapter 7), the final line of which the novel owes its subtitle. The song was the occasion of their secret engagement, and Wilibald hurried to finish his studies in order to be able to officially perform the engagement. But when the time came, Jenny held it out, and when the rich Treibel wooed her, she gave Wilibald the pass without further ado. But she still brings his love song to a lecture at every opportunity that presents itself, deeply moved by the 'higher' and 'ideal' that she sees expressed in it. She also talks a lot and likes to talk about this “higher” and everywhere indicates that she despises “property, fortune, gold” and lives entirely according to the “ideal” (Chapter 3).

She herself does not notice the diametrical contradiction between her confession to the “higher” and her actions, which the novel reveals in the following. "Jenny Treibel has a talent for forgetting everything that she wants to forget," says Wilibald Schmidt in a conversation with his nephew Marcell Wedderkopp: "It is a dangerous person and all the more dangerous because she doesn't quite know it herself, and herself sincerely imagines having a soulful heart and above all a heart for the 'higher'. But she only has a heart for the ponderable, for everything that matters and bears interest ”(Chapter 7). This characteristic comes true in the further action, in Jenny's determined resistance to a connection between her son Leopold and Wilibald Schmidt's daughter Corinna.

Wilibald would love to see his daughter marry her cousin Marcell, a promising budding archaeologist who loves her and, as soon as he has the necessary income, wants to marry. But the intelligent and independent Corinna has other plans. She wants to break out of the rather modest world of a high school professor's household and has set herself in mind to marry Leopold Treibel, a weak, dependent young man who is completely dominated by his mother and who has secretly admired Corinna for a long time. Social prestige and material prosperity appear to her as sufficient guarantees for a happy future. She throws all her charm and esprit into the scales in order to completely turn Leopold's head, and an evening party and a country party later they both secretly get engaged.

Corinna did her calculations without Jenny Treibel. She is beside herself because for her son she is a "befitting", i. H. rich lot wishes. She rejects Corinna not because she acts out of calculation, not out of love, but because apart from a "bed drawer" (with dowry linen) she would not bring anything into the marriage (chapter 12). She immediately takes the initiative, appears at the professor's house and confronts Corinna in his presence and invites Hildegard Munk - Otto's wife's sister - to Berlin to bring her together with Leopold.

In this situation, Leopold again proves to be too weak to assert himself against his mother: He limits himself to writing Corinna little letters every day in which he even speaks of fleeing to Gretna Green , but does not follow up with his words . In this tense situation, the two fathers behave in a wait-and-see manner - the Commerzienrat because he is busy organizing his election campaign, and the professor because he trusts that Corinna's common sense and sense of honor will prevail. This also happens: with the help of Schmidt's housekeeper Rosalie Schmolke, Corinna finally becomes aware of the degrading situation, breaks off the engagement and asks her cousin Marcell for forgiveness. Marcell, who has just got a position as senior high school teacher, proposes to her, and the wedding of the two sees the Schmidts and the Treibels reconciled, because apart from Leopold, all the Treibels accept the invitation to the wedding party.

Figure overview

interpretation

"Frau Jenny Treibel" occupies a special position among Fontane's novels - after all, it is one of his few novels (like L'Adultera and the unfinished work by Mathilde Möhring ) in which the bourgeoisie plays the central role. Fontane processes his experiences with a bourgeoisie in which ideals and action, moral principles and practical decision-making are diametrically opposed. The genesis of the book was marked by the quarrels about the preprint of Errungen, Verrungen , a novel that many contemporaries found offensive because of the depiction of a love affair between a flatwoman and a nobleman. Fontane had to learn how the contemporary bourgeoisie judged with double standards. Out-of-wedlock and co-marital relationships were tolerated - but you didn't want to read them in a novel. Art should serve abstract, “higher” ideals and goals and not question one's own living environment with its social discrepancies and upheavals.

Jenny is a prime example of this bourgeoisie. Like hardly any other figure in Fontane, she is portrayed as ridiculous. Jenny constantly talks about the 'higher' and that it is better to follow one's feelings and live in small circumstances, and yet she decides for herself for material wealth and urges her son to marry a boring but rich woman . Her actions are in constant contradiction to her words without her even realizing it. She refuses the professor's daughter Corinna to marry her son and forgets that it was only through such a marriage that she moved from her father's basement shop to a classy suburban villa in Berlin. And just as Jenny implements her unacknowledged material values in the family area, her husband pursues his own social dream with his political commitment. A seat in the Reichstag should ensure a title beyond the "Kommerzienrat" and a higher social position. But also Treibel's election plans bear the mark of the ridiculous. Not only does he base his political position on the product range of his chemical plants ( Berlin blue , the traditional color of Prussian uniforms), but also in the selection of his campaign assistant - a reserve lieutenant with absurd views and an inexhaustible potential for involuntary comedy - he proves to be extremely clumsy. And so his political career ends before it really begins.

In the novel, Fontane shows the social life of the bourgeoisie - a social class that tried to imitate the nobility in Berlin in the 1880s and also invited a few representatives from art and science to decorate their social events. Jenny in particular repeatedly emphasizes her strong interest in “the artistic”. Apart from an uncritical Wagner cult and the regular singing of Wilibald's “unfortunate” poem accompanied by the piano by the richly married former opera tenor Adolar Krola, this enthusiasm for art hardly bears fruit. Of course there can be no question of a real internalization of the values propagated in art, and so the subtitle of the novel and at the same time the final line of Wilibald's poem (“Where the heart is to the heart”) clearly contradicts the plot of the novel. Even with Corinna and Marcell the intellects are more likely to be found, with Leopold and Hildegard probably the company shares at best. But that is exactly what Fontane is about - to show the contradiction between claim and reality in the canon of values of upper-class society, which would rather pursue the feudal nobility than develop its own political and social concepts. Fontane himself wrote to his son Theodor (letter of May 9, 1888) that his concern was “... to show the hollow, phrase-like, lying, haughty, hard-heartedness of the bourgeois standpoint, which speaks of Schiller and Gerson [owner of a Berlin fashion salon , Note d. Author] means. "

Supplement to the above interpretation

"Frau Jenny Treibel" can be described as the "song of praise of the educated middle class". Fontane constantly contrasts the property bourgeoisie ("bourgeoisie" - embodied by the Treibels and Munks) and the educated bourgeoisie (embodied by the Schmidts, Marcell and the other high school teachers).

Ultimately, the property bourgeoisie does not come off very well; nevertheless, in Fontane's description - and condemnation - of the characters in question, there is usually a lot of benevolence and loving forbearance to be felt. This applies primarily to Treibel himself, who is good-natured, generous and thoroughly self-critical ("Who are the Treibels in the end?"). His “election agitation” is mocked, but Fontane does not reveal him as a person. Treibel clearly analyzes his own motivations as well as those of others. Fontane also suggests that Treibel - even if in the end, under the influence of his wife Jenny, the bourgeoisie triumphs in him - would have accepted a marriage between Corinna and Leopold with cheerful resignation. Otto and Leopold Treibel are also good-natured and very lovable people, which ultimately predestines them to fall “under the slippers” of strong women: Otto among his extremely conceited Hamburg wife Helene and Leopold, especially among his mother Jenny, then with Corinnas and finally among those of Helene's sister Hildegard. The bourgeois women, on the other hand, do not get away with as much goodwill as the gentlemen. The most unsympathetic character in the book - even more so than Jenny herself - is probably Helene Treibel, née Munk, the ice-cold commercial, "dynastic" ("The Thompsons are a syndicate family!") And - with their daughter Lissy - pursuing educational goals. Unlike Jenny, she doesn't think it's necessary to disguise her interests with artistic and sentimental pretexts. For them, the most important thing is the smooth and correct facade.

Fontane's approval goes to the educated middle class of Prussia, whose ideals he portrays as high and worth striving for. Of course, the vanities and "quirks" of high school professors do not get away with it. The undisputed protagonist is of course Wilibald Schmidt, for whom not only the spiritual, but above all the humane is above all. He is liberal (“If I weren't a professor, I'd be a Social Democrat!”), Sees through people and, despite a tendency to expose the weaknesses of his acquaintances with wit and sharpness, has a deep and benevolent understanding of his fellow men. He has this in common with Marcell and Distelkamp: the three figures (Schmidt, Marcell and Distelkamp) stand for the ideal of the educated citizen, whom Fontane only respects if he embodies not only knowledge and culture, but also the human. In contrast to this are Professors Kuh, Rindfleisch and Immanuel Schulze, who are also in the camp of spirit and knowledge, but are more vulnerable, vain and colder than their colleagues from the “Seven Orphans of Greece”.

Corinna is a “border crosser” between the two spheres. She actually belongs to the educated bourgeoisie, has inherited her father's gifts (“and almost smarter than the old man”), is intelligent, educated, and has many interests. But she has a "tendency towards the external". She feels drawn to the bourgeoisie and toying with it. But that is only juvenile self-deception. In the end, she sees very clearly that she “would certainly not have been very happy” had she married Leopold. She is not a person of great passions, she is talented, cheerful and enterprising and would never have been bored, not even with Leopold, on whom, as the stronger, she would have had a not inconsiderable influence anyway. But she doesn't belong in this life. Even if she has forgotten it for a while, she also embodies the ideals of the educated middle class. She respects these ideals and lives them from her youth. So it's not just intellect that connects her to Marcell; Rather, it is a basic sympathy between the two that has existed since childhood, a harmony, a real fit, respect for the same ideals. Because even in Corinna, regardless of the “external tendency”, there is a great deal of honesty and sincerity inherent in Corinna, a respect for the human that she has from her father and shares with Marcell - and which separates her from Jenny Treibel by name.

In addition to these representatives of the main groups of the novel, the bourgeoisie and the educated middle class, there are a number of secondary characters who give the whole thing the right color.

First and foremost there is Ms. Schmolke, Professor Schmidt's housekeeper and Corinna's surrogate mother, a real petty bourgeoisie and policeman widow of Berlin (“Schmolke sachte och immer ...”). It underlines Schmidt's ideals as far as these are not related to knowledge and culture: It embodies the purely human, goodness, warmth of the heart, motherliness. Fontane, of course, caricatures her folklore. Basically she is Schmidt's alter ego and underlines the humane through her presence and importance in Schmidt's household.

Fontane's socially critical realism is particularly evident in the picture he draws of the two governesses, Miss Honey and Miss Wulsten. It is a bleak and joyless picture that shows us that Corinna's fear of the "small circumstances" is by no means unfounded. The governesses are educated women from petty bourgeois backgrounds who have not managed to “save” themselves into the economic haven of marriage and are forced to earn their living as educators or society ladies in the world of the bourgeoisie. In doing so, they have to put their own life aside completely and accept complete submission and not infrequently also humiliation. In doing so, they themselves become bitter and jealous.

Quotes

- "Title: 'Frau Kommerzienratin' or 'Where the heart finds itself'. (Borrowed from Schiller's poem" Das Lied von der Glocke ": original:" Drüm check what binds itself forever, whether the heart finds its way to the heart “) This is the final line of a sentimental favorite song that the 50-year-old Kommerzienratin sings constantly in her inner circle (Schmidt wrote this song for Jenny when he was younger, when he was courting her) and through which she gains the right to the 'higher' while you in truth only the 'commercial council', that is to say a lot of money, which means 'higher'. Purpose of the story: to show the hollow, phrase-like, lying, haughty, hard-heartedness of the bourgeois standpoint, which speaks of Schiller and Gerson means. "

- “What is a novel about? He should tell us a story that we believe in, avoiding anything excessive or ugly. It should speak to our imagination and our hearts, give stimulation without getting excited; it should make a world of fiction appear to us for a moment as a world of reality, should make us cry and laugh, hope and fear, but in the end let us feel that we have lived partly among loving and pleasant people, partly among characterful and interesting people, their company gave us wonderful hours, encouraged us, clarified and taught us. That's what a novel is supposed to do. [...]

What is the modern novel about? [...] The novel should be a picture of the time to which we ourselves belong, at least the reflection of a life at the limit of which we ourselves were still standing or which our parents still told us about. "

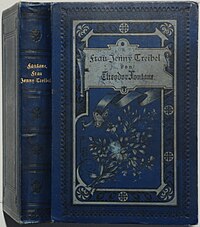

Expenses (selection)

- Theodor Fontane: Frau Jenny Treibel or “Where the heart meets the heart”. First edition. F. Fontane & Co., Berlin 1893.

- Theodor Fontane: Frau Jenny Treibel or “Where the heart meets the heart”. Novel. Structure, Berlin 2005, ISBN 978-3-351-03126-8 (= Large Brandenburger Edition, The narrative work . Volume 14. Ed. By Tobias Witt).

- Theodor Fontane: Mrs. Jenny Treibel Roman, edition at gutenberg.org

- Edgar Gross (Ed.): Theodor Fontane: Complete Works . Volume 7. Munich: Nymphenburger, 1959

- Audio

- Ms. Jenny Treibel , full text as an audio book at Librivox.org

- Walter Jens (adaptation); Hans Rosenhauer (Director): Frau Jenny Treibel: radio play . NDR 1985, Munich: DHV, 2011. ISBN 978-3-86717-737-5

Film adaptations

- 1951 - Corinna Schmidt (after Mrs. Jenny Treibel ), directed by Arthur Pohl

- 1972 - Mrs. Jenny Treibel , directed by Herbert Ballmann

- 1975 - Mrs. Jenny Treibel (with Gisela May as Jenny Treibel)

- 1981 - Mrs. Jenny Treibel (with Maria Schell as Jenny Treibel)

Secondary literature (selection)

- Simone Richter: Fontane's concept of education in “Frau Jenny Treibel” and “Mathilde Möhring”. Lack of heart formation as the reason for the failure of the bourgeoisie. VDM, Saarbrücken 2007, ISBN 978-3-8364-5010-2 .

- Humbert Settler: Fontane's background: essays and lectures . Flensburg: Baltica, 2006 ISBN 3-934097-26-X

- Christine Renz: Successful speech: on narrative structures in Theodor Fontane's Effi Briest, Frau Jenny Treibel and Der Stechlin . Munich: Fink, 1999 ISBN 3-7705-3383-6 , pp. 47-91

- Walter Müller-Seidel : Theodor Fontane. Social novel art in Germany. Metzlersche, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-476-00307-8 .

Interpretation aids (selection)

- Martin Lowsky: Theodor Fontane: Frau Jenny Treibel or Where the heart is to the heart. 4th edition, Bange , Hollfeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-8044-1906-3 (= König's explanations: text analysis and interpretation . Volume 360)

- Fritz L. Hofmann: Theodor Fontane, Mrs. Jenny Treibel: Suggested lessons and master copies . Berlin: Cornelsen, 2011 ISBN 978-3-464-61646-8

- Stefan Volk: Theodor Fontane, Mrs. Jenny Treibel . Paderborn: Schöningh, 2009 ISBN 978-3-14-022442-0

- Bertold Heizmann: Theodor Fontane, Mrs. Jenny Treibel . Freising: Stark, 2009 ISBN 978-3-86668-030-2

- Walter Wagner (ed.): Theodor Fontane, Mrs. Jenny Treibel . Stuttgart: Reclam, 2004 ISBN 3-15-008132-7

- Rudolf Schäfer: Theodor Fontane, Unterm Birnbaum, Mrs. Jenny Treibel: interpretations . Munich: Oldenbourg, 1974 ISBN 3-486-01161-8

Web links

- Theodor Fontane: Mrs. Jenny Treibel at Zeno.org .

- Full text for the Gutenberg project

- Figure lexicon on Ms. Jenny Treibel by Anke-Marie Lohmeier in the online literature lexicon portal .

- Representation and comparison of the female figures in Theodor Fontane's works

Individual evidence

- ↑ meaning the tenor Anton Woworsky (1834-1910) (Edgar Groß, 1959, p. 443)

- ↑ Quotation in: Theodor Fontane: Complete Works, ed. by Walter Keitel. Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 1963, Volume 4, p. 717. Excerpt.

- ↑ Quotation in: Theodor Fontane: Gustav Freytag: Die Ahnen. Volume I-III. Book review in the “Vossische Zeitung” on February 14 and 21, 1875. Quoted from: Theodor Fontane: Mathilde Möhring. Essays on literature. Causeries about the theater. Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, Munich 1969, p. 177. Excerpt.