Mayan gods

The pantheon of the Mayan gods is very complex. What is known today still only allows a partial view of the world of the gods . In any case, the gods were closely linked to the calendar and everyday life of the Maya . Presumably, every calendar day, month, and period, as well as each of the basic digits from zero to 20, was associated with at least one god. The fate of men was determined by the gods, and they were consulted on many projects. There were temples (often temple pyramids ), festivals and pilgrimages in honor of the gods.

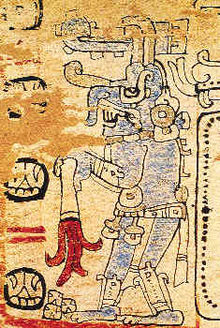

Most god beings were human-shaped and had certain attributes. Often times the same deity could appear both good and bad, young or old. There were zoomorphic hybrids and a multitude of supernatural entities in the Mayan religious tradition, all of which were interrelated and in constant motion. Individual gods were able to incorporate characteristics of other gods, which sometimes makes the demarcation or differentiation even more difficult.

Numerous offerings were made to the gods, including incense, scents of flowers and blood , animal and human sacrifices , as well as in the sacrificial cult of the Aztecs .

Sources

With the decline of the classical Mayan culture at the end of the first millennium, and again, from the 16th century, by the Spanish Conquista , along with the forced Christianization , a great deal of knowledge about the religion and gods of the Maya has been lost. The main sources are therefore the original Maya legacies. These are first and foremost the Mayan Codices , followed by numerous stone carvings and stucco work, ceramics and finally wall paintings .

prepared pages from the Codex Dresdensis

Stucco mask from Kohunlich

Vase from Petén

Wall painting from Bonampak

Some colonial manuscripts are also valuable, although they are written in Latin script and already colored in Christianity. First of all, the Popol Vuh of the K'iche should be mentioned, as well as a few other works, the Annals of the Cakchiquel or the Chilam Balam texts of the Yucatec Maya . Very knowledgeable and partly in detail, thus also of great value is also the written defense by Diego de Landa .

It was only through the legibility of the writing and the comparison of the sources mentioned that reliable knowledge of the Maya pantheon became increasingly established . All lexicons or specific literature is to be understood as an interpretation or a derivation from it. Since these works were created at different times and thus different research knowledge, there are also questionable or contradicting statements. Finally, there are also results from ethnic research and related sciences, in particular from Maya communities that are still relatively closed in themselves, such as those of the Lacandons .

Research history

As the first researcher, Paul Schellhas tried to systematize and identify the gods of the post-classical Mayan manuscripts from Yucatán. As a result, he was able to determine 15 different gods on the basis of matching characteristics, and was also able to assign your name glyphs to them. Since the writing was not yet legible at that time, he named the gods after the letter of the Latin alphabet. The system developed by Schellhas was further developed by Günter Zimmermann and finally by Karl Taube into the so-called Schellhas-Zimmermann-Taube classification and is essentially still in place today, only that most of the gods' names are legible today.

It is thanks to the meticulous and continuous, iconographic exploration of the numerous decorated facades and ceramics that have been left behind, as well as the now largely legible writing, that essentials are also known about the Mayan mythology of the classical period. In particular, the corn god and the divine twins were depicted very often. Linda Schele Elementares , among others, was able to contribute to the state of knowledge about some of the important gods of the classical period, in connection with important dates in the calendar .

Alphabetical list without claim to completeness

- Abkaknexoi, listed among the gods of fishing

- Abpua, listed among the gods of fishing

- Acantun (es), four demons or ritual stones aligned with the world, protective gods, closely ritual related to the Bacab (es)

- Acanum, listed among the gods of the hunt

- Ahau Chamahez, listed among the gods of medicine

- Ahcitzamalcum, listed among the gods of fishing

- Ah Mucen Cab, honey god

- Xmulzencab (XMulzencab), bee god or bee gods, again four, each assigned to one side of the world

- Falling God

-

Ah Puch , God A, the god of death

- Hun Ahau, Hun (a) hau (One Lord), highest lord in Mintal, the ninth and deepest level in Xibalba

- Hun Came (One Death), with Vucub Came supreme gentleman in Xibalba

- God L, the old black god, ruler of the underworld on the day of creation

- Kimi, god of death

- Kisin god of death of the Lacandons

- Uacmitun Ahau, God A '

- Vucub Came (Seven Deaths), with Hun Came supreme gentleman in Xibalba

- Yum Cimil, Lord of Death (Yucatan)

- Awilix, one of the deities worshiped in Q'umarkaj

- Bacab (es), God N (close to nature with Uayayab), four brothers who took up positions on the four sides of the world when the world was created to support heaven

- Hobnil, Bacab of the South, after Kan the fourth day of Tzolkin also Kanalbacab or Kanpauahtun

- Canzienal, Bacab of the East, after Muluc the ninth day of Tzolkin also Chacalbacab or Chacpauahtun

- Zaczini, Bacab of the North, after in Ix the 14th day of Tzolkin also Zacalbacab or Zacpauahtun

- Hozanek, Bacab of the West, after in Chauc (= Kawak) 21st day of Tzolkin also Ekelbacab or Ekpauahtun

- Bolon-Ahau, 1551–1561 a calendar god

- Bolon Tiku , bolón-ti-ku (Nine Lords of the Night), Nine Gods of the Underworld , who rule over two months of Haab and one month of Tzolkin , opponents of the Oxlahun Tiku

- Bolon Yokte 'K'uh, El Tortuguero , Stele 6, deity to perform in a big act on December 21, 2012

- Buluc Chabtán, god F, earth deity, as god of war and sacrifice, also related in nature to Ek Chuah and Etz'nab

- Buluc-Ahau, 1541–1551 a calendar god

- Cabracán, (Kab'raqan = the two-legged) the shaker, an earthquake god

-

Chac (es), god B, the rain god

- Chac Xib Chaac = Red Chaac of the East

- Sac Xib Chaac or Zac Xib Chaac = White Chaac of the North

- Ek Xib Chaac = Black Chaac of the West

- Kan Xib Chaac = Yellow Chaac of the South

- Chacacabtum,

- Chan K'uh, god of heaven

- Cama Zotz, bat god

- Chicchan, god H, rain god of the Chortí

- Chimalmát, wife of Vucub Caquix, mother of the earthquake demons Cabracán and Zipacna , four of the Chortí in the role of world bearer instead of the Bacab

- Citolontun, listed among the gods of medicine

- Cuculcan (Gucumatz, Gugumatz, Kucumatz, Kukulcan, Kulkulcan, Kukumatz = feathered serpent ), an element god

- Ekchuah , god M, god of merchants, travelers and prosperity but also black warlord, related in nature to god L

- Etz'nab (knife edge), god Q, a sacrificial god, related in nature to Buluc Chabtán

- Hunab Ku, God above the gods, only god, draft of an integration of the Christian god in the 16th century under the influence of mission

- Hunahpú , one hunter, first hunter, one of the divine twins or twin heroes, see also: Ixbalanqué

- Hun Nal Yeh (Ah Mun) the (young) corn god, god E.

- Huracán , the giant, the one-legged, god of the storm, related in nature to K'awiil , presumed or possible namesake of Hurricane , as U K'ux Kaj (heart of heaven) important creator god in Popol Vuh

- Ixbalanqué (Xbalanque), one of the divine twins or twin heroes, see also: Hunahpú

- Ixbunic (Ixhunie), among the female. Called deities who were worshiped on Isla Mujeres in 1517

- Ixbunieta (Ixhunieta), among the female Called deities who were worshiped on Isla Mujeres in 1517

-

Ixchel , goddess O, goddess of the moon and fertility, earth goddess, patroness of water, the rainbow and pregnant women and inventor of the art of weaving, wife of Itzamná , i.e. Ixchel

- Ixcanleom, goddess of fertility (appearance of the Ixchel )

- Ixchebeliax, among the female Named deities who were worshiped on Isla Mujeres in 1517, as Ix Chebel Yax wife of Itzamná , i.e. Ixchel

- Ix Chup (Ix Ch'up), embodiment of a young nursing mother (manifestation of the Ixchel )

- Ixmucané (Xmucane = the old woman; Alóm = the woman who gave birth, the great mother; also Chulmetik = woman moon in Chiapas ), creator goddess, perhaps the equivalent of the K'iche to Ixchel

- Ixpiyacóc (Xpiyacoc = the old man; K'ajolom = the sons-producer, the great father; Chultotik = Lord Sun in Chiapas ), god of creation

- Ixtab , goddess of suicide

- Itzamná , god D, (Izamnakauil; Cinchau-Izamná), first and highest among the Mayan gods

- Jakawitz (Q'aq'awitz, Hacavitz = fire mountain), fire or volcano god of the K'iche

- Kab k'uh, earth god

- K'awiil , god K, lightning god, god of dynasties and ancestry

- Kinchahau , god G, the sun god

- Oxlahun Tiku, oxlahun-ti-ku (13 lords of heaven or 13 lords of the day), opponents of the Bolon Tiku

- Uayayab (Uayeb), God N (close to nature with Bacab), God over the five days of the unlucky month of Uayeb des Haab

- Kanuuayayab

- Chacuuayayab

- Zacuuayayab

- Ekuuayayab

- Uuc-Ahau, 1561–1571 a calendar god

- Vucub Caquix (Uucub-k'aquix = seven feathers of fire, seven parrot), a calendar god, father of the earthquake demons Cabracán and Zipacna

- Yum Kaax, a vegetation and forest god, often confused with the corn god

- Zipacna , the strong, an earth or mountain god, in the form of a crocodile

- Zuhuyzib Zipitabai, listed among the gods of the hunt

literature

- Diego de Landa : Report from Yucatan , Stuttgart 2007 → cf. also: Relación de las cosas de Yucatán , ( PDF ; 513 kB), ( Spanish )

- Wolfgang Cordan (translator): Popol Vuh. The Book of the Council , 1962 → cf. also: Allen J. Christenson (transl.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007 ( English )

- David M. Jones and Brain L. Molyneaux: Mythology of the New World: An Encyclopedia of Myths in North, Meso and South America , Reichelsheim 2002

-

Nikolai Grube (Ed.): Maya, Gottkönige im Regenwald , Potsdam 2012

- Karl Taube : The Gods of the Classical Maya. In: Maya, Gottkönige im Regenwald , Potsdam 2012, pp. 263–277

- Elisabeth Wagner: Creation myths and cosmology of the Maya In: Maya, Gottkönige im Regenwald , Potsdam 2012, pp. 281–292

- Sylvanus Morley , Robert J. Sharer : The Ancient Maya , Stanford 1994, pp. 526-535 (English)

- Paul Schellhas : The gods of the Maya manuscripts : A mythological cultural image from ancient America , Dresden 1897 → cf. also: Representation of Deities of the Maya Manuscripts , Cambridge 1904 (English)

Web links

- Deidades Principales del Panteón Maya - after Sylvanus Morley : La civilización Maya. Edición revisada por George W. Brainerd y notas de Betty Bell. Traducción al español de la tercera edición en inglés, de Cecilia Tercero. Fondo de Cultura Económica, México 1972 ( résumé ) (Spanish)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Diego de Landa : Report from Yucatan , Stuttgart 2007.

- ↑ Paul Schellhas : The gods of the Maya manuscripts : A mythological cultural image from ancient America , Dresden 1897

- ↑ Günter Zimmermann: The Hieroglyphs of Maya Manuscripts , Hamburg 1956, pp. 162–168 ( digitized from Google Books )

- ^ Karl A. Taube : The major gods of ancient Yucatan , 1992 ( digitized at Google Books )

- ↑ Linda Schele, Mary E. Miller: The Blood of the Kings. Ritual and Dynasty in Maya Art. London and New York, 1993.

- ↑ a b c Landa (Lit.), p. 147.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 156.

- ↑ a b c d e f Jones u. Molyneaux (Lit.), p. 92.

- ↑ David A. Freidel, Linda Schele : Kingship in the late preclassic Maya Lowlands: the instruments and places of ritual power . In Michael E. Smith, Marilyn A. Masson: The Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: A Reader. Oxford 2000, pp. 422-440.

- ↑ a b Landa (Lit.), p. 146.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 145.

- ↑ Jones et al. Molyneaux (lit.), p. 154.

- ^ John Eric Sidney Thompson : Maya History and Religion , Oklahoma 1990, p. 311.

- ↑ The Bee God - Ah Mucen Cab - The History of the Mayas

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 98.

- ↑ Grube at all (Lit.), p. 284, Fig. 445.

- ↑ Jones et al. Molyneaux (lit.), p. 127.

- ↑ Grube at all (Lit.), p. 276.

- ↑ Allen J. Christenson (trans.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007, pp. 198 ff, FN 552, 585.

- ↑ Ralph L. Roys : Ritual of the Bacabs, Oklahoma 1965

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), pp. 101-103, 149.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 149.

- ↑ a b c Landa (lit.), p. 160.

- ↑ a b c Ralph L. Roys : The Book of Chilam Balam of Chuyamel . Washington DC, Carnegie Institution 1933, pp. 51–54 ( PDF ; 3.2 MB).

- ↑ a b c Jones et al. Molyneaux (lit.), p. 95.

- ↑ Allen J. Christenson (transl.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007, p. 82, FN 169; Pp. 96-100.

- ↑ a b Landa (Lit.), p. 107.

- ↑ a b Grube at all (Lit.), p. 264.

- ↑ Jones et al. Molyneaux (lit.), p. 98.

- ↑ Allen J. Christenson (transl.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007, p. 82, FN 170.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 145.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), pp. 22, 150-153.

- ↑ Jones et al. Molyneaux (lit.), p. 110.

- ^ William F. Hanks: Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross. 2010.

- ↑ Allen J. Christenson (transl.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007, p. 59, FN 56; P. 60, FN 62.

- ↑ a b c Landa (lit.), p. 13.

- ↑ Codex Madrid pp. 75/76.

- ↑ Jones et al. Molyneaux (lit.), p. 115.

- ↑ Jones et al. Molyneaux (lit.), pp. 115-116.

- ↑ a b Allen J. Christenson (trans.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007, p. 52 ff, FN 14 ff; P. 142, FN 361.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 99.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 106.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 143.

- ↑ Allen J. Christenson (transl.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007, pp. 198 ff, FN 553, 585.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), p. 104.

- ↑ Allen J. Christenson (transl.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007, pp. 198 ff, FN 551, 585.

- ↑ Grube at all (Lit.), p. 269.

- ↑ Grube at all (Lit.), p. 369.

- ↑ Wolfgang Cordan (transl.): Popol Vuh. The Book of the Council , 1962, p. 206, EN 112.

- ↑ Jones et al. Molyneaux (Lit.), p. 151.

- ↑ Landa (Lit.), pp. 103, 136.

- ↑ a b c d Landa (Lit.), p. 103.

- ↑ Jones et al. Molyneaux (Lit.), p. 152.

- ↑ Allen J. Christenson (transl.): Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People , 2007, p. 82, FN 168; P. 89, FN 194; Pp. 93-96.