George Santayana

George Santayana (born December 16, 1863 in Madrid , † September 26, 1952 in Rome ; actually Jorge Augustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana) was a Spanish philosopher , writer and literary critic. Santayana is one of the most influential exponents of 20th century American philosophy and is also considered a leading exponent of critical realism .

biography

Santayana was born in Spain and remained a Spanish citizen throughout his life. His father, Agustín Ruiz de Santayana, came from the Spanish diplomatic society, studied law in Madrid and trained as a professional painter. After three trips around the world, he worked as governor on Batang, a small island in the Philippines . Santayana's mother, Josefina Borrás, was the daughter of a Spanish civil servant and grew up in the Philippines.

His parents emigrated with him to Boston , USA, in 1872 . Here his first name was anglicized to George, under which he later became known in the English-speaking world. He studied first at the Boston Latin School and then under William James at Harvard University . After graduating from Harvard in 1886, he studied for almost two years in Berlin , where he wrote his dissertation on the philosophy of Rudolf Hermann Lotze , which he submitted when he returned to Harvard in 1890 and subsequently became a member of the philosophy faculty.

In 1912, Santayana used the inheritance after the death of his mother to leave behind the academic constraints he did not like. He first lived in Paris for a few years, later in Oxford , before settling in Rome in 1925 . He did not return to the United States and never accepted American citizenship. During the 40 years in Europe he wrote 19 books and held several academic positions. After George Santayana's efforts to leave Europe before the outbreak of war in Italy had failed , he retired to the Catholic nursing home of the "Monastery of the Blue Nuns" in Rome until his death in 1952.

Santayana was never married. On the basis of some statements, many biographers assume a homosexual orientation of Santayana.

Santayana's disciples also achieved fame and honor; the best known are TS Eliot and Walter Lippmann , but Harry Austryn Wolfson , Gertrude Stein and Wallace Stevens are also among them.

In 1943 he was elected an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters .

Work and meaning

George Santayana's first book, Sonnets and Other Verses (1894), is a volume of poetry. Drama and poetry remained his main publications until the turn of the century (e.g. Lucifer: A Theological Tragedy, 1899). With their naturalistic attitude, these works are considered to be groundbreaking for modern literature. It was not until 1904 that Santayana turned his full attention to philosophy. The recording and representation of the relationships between literature, religion and philosophy remained his most important concern.

In 1896, Santayana published The Sense of Beauty, a summary of his lectures on aesthetics that he had given at Harvard University . The subject of the book is the nature and origin of beauty as a human feeling. The special meaning in its historical context is that the question of beauty is treated as a subject of science . The role of God becomes metaphorical instead of metaphysical . The perception of beauty is of Santayana as with pleasure ( pleasure described connected) without it would arise solely from pleasant experience; Beauty is the "objectification" of pleasure ( pleasure ) and manifestation of Perfect . Santayana later distanced himself from the views presented in this book and, according to an anecdote by Arthur C. Danto, even claimed that the book was only produced under pressure from the faculty.

In Interpretations of Poetry and Religion (1900), George Santayana outlines a naturalistic interpretation of poetry and religion. Both are therefore expressive celebrations of life , whereas science provides explanations of natural phenomena. If these two are misunderstood as science, however, they lose their value and their beauty. Poetry and religion are based on the consciousness that has arisen through human interaction with their environment. In Santayana, poetry and religion are given a naturalistic basis and their meaning is identical. The book caused some violent reactions. William James called it the "perfection of rottenness" ; Henry James, on the other hand, wrote that he would "crawl through London" to speak to Santayana about the book.

In his first major work on cultural philosophy, The Life of Reason (1905/6), Santayana designed a systematic presentation of his ethical philosophy and at the same time established his reputation as one of the most important philosophers of the new century. Based on the natural conditions, he tried to discover the origins and meaning of science, art and religion. These areas appear as different, but nevertheless equivalent components of a symbolist philosophy.

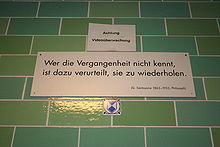

Santayana's well-known warning appears in The Life of Reason : “ Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” are condemned to repeat it. Today this quote is mostly used in a historical-moral sense. In the original context, however, Santayana argues against a naive belief in progress and at the same time against the perfectionism and idealism of Christianity. In contrast to these he sets a pragmatism that only knows progress as a change based on the awareness of the past. Without this memory, i.e. H. without this mindset, there is no progress and no learning from experience.

Santayana published a highly acclaimed literary critical work in 1910 with Three Philosophical Poets . Using Lucretius , Dante and Goethe , he traces the main currents of speculative, western philosophy: materialism and naturalism, Platonism and Christianity, as well as idealism and natural-philosophical romanticism .

The educational novel The Last Puritan ("The Last Puritan") published in 1935 was an international success, but remained his only novel. Many of the elements in it are autobiographical and reflect Santayana's relationship with America.

His book The Christ Idea in the Gospels is "a great advance towards a poetic theology of Christianity", judged Alois Dempf .

philosophy

naturalism

In his autobiography Santayana emphasizes a consistent continuity in his development from an idealism of his childhood, through an intellectual materialism , to a fully formed naturalistic perspective as an adult. He developed a comprehensive presentation of his materialism with Skepticism and Animal Faith 1923. For Santayana, knowledge and belief are not the result of rational argumentation here. He also rejects sophisticated epistemological and metaphysical justifications. Rather, the basis of knowledge are natural conditions and a so-called "Animal Faith", a fundamental, instinctive and non-rational belief in the existence of the world and the pragmatic approach to action and knowledge. Ultimately, the meaning and value of an action is derived from our physical condition and natural environment.

The critical realist Santayana also argues in the context of “Animal Faith”. Things in the world can be illusory, but belief in them is based on a “rational instinct” based on pragmatic success. So, according to Santayana, there are inevitable beliefs that are determined by our nature.

The psyche is for Santayana a material manifestation of the Spirit (org. Minimum) and a bundle of beliefs that characterizes an individual.

ontology

George Santayana is one of the few 20th century philosophers who has worked out a complete metaphysical system. Here he designs an extensive ontology and distinguishes between four areas of being. The terminology is based on the ancient usage of the terms.

- Essence

Santayana defines essence as that which exists in the broadest sense. Everything is experienced mediated only through the being. If the consciousness is directed only towards the being, then all knowledge disappears, which according to Santayana is a belief mediated by symbols. The awareness of essence is only awareness itself.

- Matter (matter)

Matter is pointless and “incomprehensibly irrational”. Knowledge of matter is also symbolic for Santayana. Thus the knowledge of (natural) science is no different symbolic than the knowledge of poetry and religion. In this sense, Santayana's materialism is non-reductive. For him matter is the basis of all existence and as such also the origin of nature, spirit and morality and the only effective substance.

- Truth (truth)

Based on the realm of being of the being, the truth is the link between matter and being. Truth for Santayana is fully objective and irreducible to experience.

- Spirit

The definition of mind corresponds essentially to the general everyday meaning of consciousness. The realm of being of the spirit thus shows a stronger affinity to the realm of being matter.

Epiphenomenalism and Panpsychism

Some philosophers characterize the relationship between spirit and matter in Santayana's thinking as an epiphenomenalism . However, he did not understand mind itself as an object on which an effect can exist. The true essence of the spirit, then, is to give meaning to the world. Santayana has explicitly positioned himself as an opponent of panpsychistic views. Timothy Sprigge points out, however, that in the ontology Santayana ultimate events ("final events") can have an effect (on the being) that is not plausible due to a naturalistic view. In this sense he speaks of an “unwitting touch of panpsychism” in Santayana's thinking.

Works (selection)

- The Sense of Beauty (1896)

- The Life of Reason (1905/06)

- Three Philosophical Poets (1910)

- Egotism in German Philosophy (1916)

- Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies (1922)

- Skepticism and Animal Faith (1923)

- Dialogues in Limbo (1925)

- Platonism and the Spiritual Life (1927)

- The Realms of Being (1927)

- The Realm of Matter (1930)

- Some Turns of Thought in Modern Philosophy (1933)

- The Last Puritan. A Memoir in the Form of a Novel (1935) (German: The last Puritaner. The story of a tragic life. )

- Obiter Scripta (1936)

- The span of my life . From the American by Wolfheinrich vd Mülbe. Hamburg 1950.

- The Christ idea in the Gospels . A critical essay. Munich 1951.

literature

- Daniel Moreno: Santayana the Philosopher: Philosophy as a Form of Life . Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2015. Charles Padron (U).

- John Salmon: On Santayana. Wadsworth, Belmont 2006.

- Armen Marsoobian, John Ryder: The Blackwell Guide to American Philosophy. Blackwell, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-631-21622-7 .

- John McCormick: George Santayana: A Biography. Transaction, Somerset 2003, ISBN 978-0-7658-0503-4 or ISBN 0-7658-0503-0 .

- Hartmut Sommer: The Catholic Atheist: The last refuge of George Santayana in Rome. In: Ders .: Revolte and Waldgang: The poet philosophers of the 20th century. Lambert Schneider, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-650-22170-4 , pp. 87-110.

- Albert Veraart: Santayana , in: Jürgen Mittelstraß (Hrsg.): Encyclopedia Philosophy and Philosophy of Science. 2nd Edition. Volume 7. Stuttgart, Metzler 2018, ISBN 978-3-476-02106-9 , pp. 215 - 216 (with a detailed list of works and literature)

Web links

- Literature by and about George Santayana in the catalog of the German National Library

- Herman Saatkamp: George Santayana. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Matthew Caleb Flamm: Entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Honorary Members: George Santayana. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 20, 2019 .

- ↑ James D. Hart (1995). The Oxford Companion to American Literature [1] , p. 598, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506548-0

- ↑ Stephen Davies; Kathleen Marie Higgins; Robert Hopkins; Robert Connector; David E. Cooper (2009). A Companion to Aesthetics. John Wiley & Sons. Pp. 511-512. ISBN 978-1-4051-6922-6 .

- ↑ George Santayana; William G Holzberger; Herman J Saatkamp (1988). The sense of beauty: being the outlines of aesthetic theory. Cambridge, Mass .: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-19271-3 .

- ↑ Marsoobian / Ryder: The Blackwell Guide to American Philosophy (see literature), pp. 135ff.

- ↑ Marsoobian / Ryder: The Blackwell Guide to American Philosophy (see literature), p. 141.

- ^ The Life of Reason : Reason in Common Sense, Scribner 1905, p. 284.

- ^ John McCormick: George Santayana: A Biography . New York: Alfred A. Knopf 1987, p. 141.

- ↑ Philosophisches Jahrbuch 62 (1953) 23.

- ^ Santayana: Skepticism and animal faith (1923), p. 40 (1937).

- ↑ a b Michael Hampe, Helmut Maassen (ed.): The Realms of Being (1942), Suhrkamp 1991.

- ↑ Timothy Sprigge: Santayana and Panpsychism. Bulletin of the Santayana Society 2, Fall 1984, chap. 1, pp. 7-8.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Santayana, George |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Santayana, Jorge Augustín Nicolás Ruiz de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish philosopher and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 16, 1863 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Madrid |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 26, 1952 |

| Place of death | Rome |