History of Bad Grönenbach

The history of Bad Groenenbach Bach begins after corresponding findings in the Bronze Age and is about the Roman province Raetia , through the Middle Ages with the rule of various noble families (local local nobility, Rothstein , Pappenheim , Fugger ) to pursue the modern era, as Grönebach from the Imperial Abbey of Kempten by the secularization of Bavaria fell. The place was first mentioned in a document in 1099. In the 16th century, Grönenbach was the scene of religious disputes in the course of the Reformation and has since been home to one of the oldest Reformed communities in Germany. Grönebach 1954 as Kneipp spa town in 1996 and as a Kneipp spa accepted since then called the place Gronenbach . Today the place is in the administrative region of Swabia in Bavaria .

Prehistory and early history

Several soil monuments from the Mesolithic and the Neolithic are known from the vicinity of the Bad Grönenbach community . Concrete finds from the village of Ittelsburg , which belongs to Bad Grönenbach, date from the Bronze Age . The so-called Ittelsburger Fund - a treasure find - consisting of seven rag axes , a chisel , a dagger blade and several pieces of raw material and gold wire, dates from between 1800 and 1200 BC. There are other ground monuments from the Hallstatt and Latène times , including the Fliehburg in Ittelsburg . In the year 15 BC During their campaigns , the Romans under Drusus and Tiberius conquered the later Roman province of Raetia and defeated the local Celtic tribe of the Vindeliker , whose branch tribe , the Estionen , settled in the area around Kempten. The Roman road from Cambodunum ( Kempten ) to Caelius Mons ( Kellmünz ) ran east of Bad Grönenbach . The ground monuments of the Roman Burgi near Schoren , a district of Dietmannsried , and near Waldegg , a wasteland of Bad Grönenbach, to the former Burgus in Woringen, bear witness to this .

During the so-called imperial crisis of the 3rd century , the Romans in the province of Raetia were confronted with raids by the Alemanni , for example in the years 259/260. In the course of the later decades, however, the empire was able to stabilize its rule again. It was not until the 5th century that the Roman troops were finally withdrawn from Raetia by the Italian king Odoacer after the last Western Roman ruler had been deposed . This enabled the Alemanni to fully colonize the area. As early as the 6th century, however, the Alemanni and with them the Bad Grönenbach area came under Franconian sovereignty. For this time, from around the beginning of the 8th century, it can be assumed that the so-called nobles of Grönenbach had the "settlement on the green stream" - from which the later name Grönenbach was derived - under their rule. The people named in some literature "Gottschalk von Grönenbach" and "Petermann von Ruotenstein", who are said to have died in the Battle of the Feilenforst in 727 , are not historically proven.

middle Ages

Early and High Middle Ages

Even if the aforementioned noble Gottschalk von Grönenbach is probably an invention, there were other representatives of a Grönenbach local nobility who belonged to the Guelphs . Its members had possessions in Wolfertschwenden , Ittelsburg and Ochsenhausen . A Hatto von Beningen, around 973 a monk in the Ottobeuren monastery , is considered the oldest ancestor of this local nobility. The first documented mention of Grönenbach was in 1099, when the brothers Hawin, Adelbert and Konrad (sons of a noble Hatto) donated their inheritance to the St. Blasien monastery at Ochsenhausen, Rot and Westerheim, with the proviso that a priory be set up in Ochsenhausen. Whether this Hatto is the same person as the one named in 973 cannot be said for sure, as the name Hatto was often given. Grönenbach is mentioned in a document as the place of origin of the brothers. Hawin was also mentioned in connection with the Guelph castle in Wolfertschwenden . A Hatto von Grönenbach testified on February 16, 1130 the confirmation of the Ursberg monastery . The three brothers named are named in a document dated January 12, 1152, with which Konrad III. confirmed the donation to the monastery of St. Blasien. In 1170 the lay priest Berthold von Grönenbach and his brother Ulrich von Grönenbach, monk in the St. Georg monastery in Isny , left a forest near Adelegg to the monastery. With Adelheid von Grönenbach, a nun in the Ottobeuren monastery, the local nobility of Grönenbach and Wolfertschwenden died out after 1260.

The main castle of this Welf noble family was on the Schloßberg in Wolfertschwenden. Apart from trenches, nothing remains of it. Other neighboring castles existed at Bossarts and near Ittelsburg. Both castles are only castle stables ; there are the Burgstall Felsenberg and the Burgstall Neuittelsburg . At that time, the castle in Grönenbach was not at the site of the later built and still existing High Castle , but with the church of St. Philip and Jacob on the Kirchberg, consecrated in 1136 . The Guelph castle was probably destroyed in 1129 and was not allowed to be rebuilt in the same place. With the entry of several family members into monasteries and the extinction of the Grönenbach nobility, the Kempten monastery came into possession of the Grönenbach area. As a result, the monastery Kempten Grönebach awarded by the year 1695 without interruption as a fief .

Late Middle Ages

The Kempten Monastery awarded the fiefdom of Grönenbach to the noble family of Rothenstein, whose ancestral castle is around 2 km southwest of Grönenbach. You are named with Konrad from 1293 as the owner of the dominions Woringen and Grönenbach. According to Konrad, the noble family of Rothenstein split up into several lines. For Grönenbach, the line of Ludwig "the old" von Rothenstein is decisive. This came into the possession of Grönenbach in 1330 and in 1339 assigned various Kemptic fiefdoms to his wife Elise von Schwarzenburg. When Ludwig the Old died, his possessions were divided among his sons. With this division of the estate, the rule of Grönenbach passed to his son Ludwig the Younger. In 1357 he sold the church set of Grönenbach as a fief to his uncle Heinrich. He expanded his holdings in Grönenbach through acquisitions from the property of Hans Dodel. Around the middle of the 14th century, the rule of Grönenbach fell as heir to Hans Rizner von Memhölz and later to Hans the Syrgen von Syrgenstein . In 1384, the brothers Ulrich and Konrad von Rothenstein, nephews of Ludwig the Younger, bought back the castle and estate of Grönenbach from Hans the Syrgen. Konrad was married twice. The daughter Korona (or Corona) emerged from her first marriage with Ursula von Hattenberg. Ursula von Hattenberg brought further possessions into the marriage, including Kalden Castle near Altusried . Ursula appointed her daughter Korona as heiress. In his second marriage, Konrad was married to Hildegard von Freundsberg (Frundsberg), from whom the sons Ludwig and Thomas emerged.

Rothenstein Castle before it collapsed in 1873

In the early days of the Rothenstein rule over Grönenbach, the High Castle was built. The start of construction is dated to the 12th century, in the largely existing form it was probably built in the middle of the 14th century. Another brother, Christoph von Rothenstein, has been handed down as parishioner of Grönenbach from 1377. He was probably pastor in Grönenbach until his death around 1405 . In a document from 1405, the brothers Konrad and Ulrich as well as Haupt II. Von Pappenheim , with whom Korona was married, regulated the donation of the great and small tithe in the parish of Grönenbach to the respective pastor, who had to employ a chaplain . When Konrad died, disputes developed between the brothers Ludwig and Thomas von Rothenstein on the one hand and their half-sister Korona and her husband, Haupt II. Von Pappenheim, on the other over the inheritance. In 1409 the parties agreed on a division of the estate. Ludwig and Thomas received Grönenbach and Rotenstein with both fortresses and all the goods that Konrad had owned on the right of the Iller . Another division of the inheritance among the three siblings resulted after the death of their uncle Ulrich. Korona received half of the village of Woringen and the two brothers received the other half. Since Ludwig and Thomas were minors at that time, they were represented by a guardian. He sold her half of Woringen in 1412 to Korona. In 1440 the brothers Ludwig and Thomas divided their property. In 1446, Ludwig von Rothenstein acquired the rule of Theinselberg with the high jurisdiction that the Kempten monastery had granted to Grönenbach, Kalden and Rothenstein. Since Thomas was childless when he died (between 1471 and 1473), he bequeathed all of his possessions to his brother Ludwig. Ludwig himself was also able to expand his possessions in the course of time, he obtained rights and fiefs in Zell (1460), Herbisried (1477) and Minderbetzigau (1478). Since 1473 he was the owner of the dominion and the castle Leonstein in Carinthia . Was married Ludwig von Rothstein with Jutta of Hürnheim . Since this marriage did not result in any descendants, Ludwig and Jutta set up various foundations, including a perpetual mass in Grönenbach in 1471 and the Heilig-Geist-Spital in 1479 to accommodate poor people and provide food for pilgrims . In 1479 the parish church of St. Philip and Jacob was elevated to a collegiate foundation for twelve lay priests. A few years after the foundations were established, Ludwig von Rothenstein died on May 8, 1482 at his Leonstein Castle in Carinthia. His body was transferred to Grönenbach and, on his previous instructions, buried there without a helmet or shield. Since Ludwig died childless and did not get along well with his Rothenstein relatives, he had his property and his fiefs in the towns of Theinselberg, Grönenbach, Rothenstein and Kalden, his nephew Heinrich XI. von Pappenheim , the son of his sister Korona. He died in the same year and bequeathed him to his sons. With that the rule of Grönenbach passed to the Pappenheimers . The epitaph of Louis is in the Collegiate Church of St. Philip and James in Gronenbach and Niklas Turing is credited.

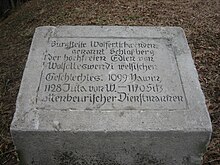

Inscription plaque on the hospital church

Coat of arms of the couple Ludwig von Rothenstein and Jutta von Hürnheim at the collegiate monastery

Modern times

Pappenheimer (from 1482 to 1612)

In earlier literature the transition of the Allgäu property around Grönenbach from the Rothensteiners to the Pappenheimers is not detailed or explained. However, Joseph Sedelmayer expresses himself very specifically in the history of the market town of Grönenbach from 1910, which he published . Since Ludwig's sister, Corona von Rothenstein, had already died when he passed away, her son Heinrich was appointed as heir. He died either in the same year as Ludwig (1482) or in 1484; the sources do not clearly state the year of his death. It is therefore uncertain whether Heinrich was still able to personally take over his property in Grönenbach. After his death, his sons Wilhelm I and Alexander I agreed on a division of property. According to various information in the literature, this happened either in 1484 or 1494. With this, Wilhelm I became the founder of the Pappenheim-Rothenstein line and Alexander I the founder of the Pappenheim-Grönenbach line, although their possessions in the localities cannot be clearly demarcated; the other brothers were also given property in Grönenbach. Since Grönenbach was actually a male fiefdom of the prince monastery of Kempten, it should only have been inherited in male descent . Against this, Ludwig's still living Rothenstein relatives, Achar and Arbogast von Rothenstein, took action, which resulted in lengthy disputes. Although 20 soldiers from the Swabian League were present in the High Palace, they succeeded in driving Alexander in 1503 and Wilhelm in 1506 from Rothenstein. After a call for help from the two Pappenheimers, the Swabian Federation marched into Grönenbach on October 9, 1508 with 15 riders and 70 soldiers. However, this was not enough to end the disputes. It was not until the threat of sending another 100 sticks and 2000 farmhands that the Rothensteiners relent. With the judgment of the Innsbruck government , the Rothensteiners were given their ancestral castle in 1508. However, the castle only remained in their possession until 1514 and was sold back to the Pappenheimers that year. Heinrich XII. von Pappenheim , another brother of Wilhelm and Alexander, died in 1511 and shared his Allgäu property between Alexander and Wilhelm and their descendants. In the time of Wilhelm and Alexander von Pappenheim awarding the falling market law by Frederick III. to Grönenbach. This event was depicted by the painter Ludwig Eberle as a sgraffito on the town hall built in 1936/1937 .

Alexander I is described by Matthäus von Pappenheim in his chronicle as "homo agrestis & rudis" and not averse to the arms trade and was a participant in tournaments , including 1484 in Ingolstadt . Alexander I, who died in 1511 and was buried in Grönenbach, bequeathed his property to his son Heinrich Burghard I. His son Alexander II came into the possession of Grönenbach. Alexander's only son Joachim III. died in 1599, and Alexander II appointed his daughter Anna as heir. Since Grönenbach was a man's fief, this should not have been the heir. Anna was first married to Philipp von Rechberg and widowed from 1611. She entered into her second marriage to Otto Heinrich Fugger and remained married to him until her death in 1616. With this marriage and the inheritance of Alexander II, the Fuggers came into the possession of Grönenbach. The line Pappenheim-Grönenbach from Alexander I. is with the death of Joachim III. and Annas went out.

Sgraffito of the 1485 market rights at the town hall

Wilhelm I's second line Pappenheim-Rothenstein not only had possessions in Rothenstein, but also in Grönenbach and other areas, including Kalden Castle . Wilhelm appointed his son Wolfgang I as heir , he owned half of the Allgäu estate and an eighth of the Pappenheim rulership as well as the castles in Rothenstein, Kalden and Polsingen. After Wolfgang I died in 1558, his sons Philipp, Wolfgang and Christoph began a pilgrimage to Jerusalem . However, Philipp von Pappenheim decided to break off his pilgrimage in Venice and traveled back home via Zurich in Switzerland . During his stay in Switzerland, he met the Reformed preacher Bächli and accepted the Calvinist creed. On his return to Grönenbach, he introduced this creed to his subjects according to the principle of cuius regio, eius religio . Since his cousin Alexander II remained Catholic in Grönenbach , they both agreed in 1560 to pay the canons and the Catholic priest as well as the Calvinist preacher from the income from the monastery. From this time on, the Catholic collegiate church of St. Philip and Jacob was used as a simultaneous church. The brothers Conrad, Wolfgang, Christoph and Philipp jointly built the Lower Castle in Grönenbach in 1563 as a widow's seat . An inscription panel above the entrance with the coat of arms of Pappenheim (left) and von Roth (right) bears the following inscription:

“When one zalt 1563 jar dises haṽs zṽ lieb aṽfgebawen was iṽnckfraw walpṽrg marshalckin zṽ bappenhaim. dṽrch ire vetern the four priders ingenain conradt wolff christoff ṽnd philipen die got vor glnglick wel schiitzen. "

"When one counts 1563 year, this house was built to love Jungfrau" Walburg ", Marschallin von Pappenheim through her cousins, the four brothers, in total: Conrad, Wolf, Christof and Philippen, who will protect God from misfortune."

In 1613, Philip obliged his heirs to maintain the Reformed community in Grönenbach. Although the Reformation in Grönenbach only made a lasting impression under Philipp von Pappenheim, the new teaching found a few followers in Grönenbach as early as the 1520s, for example with the lay preacher Hans Häberlin . He appeared publicly as a preacher and was arrested in April 1526 by order of the Swabian Federation and hanged on July 14, 1526 at Leubas . As early as 1612, after the death of Alexander II, Philipp took over the seniorate of the Pappenheim family. Philipp appointed the son of his cousin Alexander II, Wolfgang Christoph von Pappenheim , as heir to his Pappenheim possessions , who appointed his cousin Maximilian von Pappenheim as a universal heir . With his death in 1639, the Pappenheim line of Allgäu-Stühlingen , which with Heinrich XI. was founded by Pappenheim, finally.

The German Peasants' War fell during the time of Pappenheim's rule in Grönenbach . In addition to other local groups, including from Legau and Altusried or the heap on the Wurzacher Heid, farmers from Grönenbach also took part in the uprisings and joined the Baltringer heap . The Grönenbacher Haufen was called to help by the Wurzachers and their colonel, Pfaffe Florian von Aichstetten. The Grönenbachers also besieged the high castle in Grönenbach and the castle in Rothenstein. In anticipation of the impending siege, Wolfgang von Pappenheim and the widow of Marshal Alexander, Barbara von Ellerbach, brought themselves to safety in Kempten . The canons from the collegiate monastery fled to Kempten. In 1503 they had already acquired the Zum Weißen Hund inn as a refuge, which remained in the possession of the monastery in Grönenbach until 1695. The peasant uprising was ended in the battle of Leubas on July 15, 1525.

Fugger (from 1612 to 1695)

Through the second marriage of Anna von Pappenheim to Otto Heinrich Fugger , Alexander II's part of the Grönenbach reign passed from the Pappenheimers to the Fugger . The marriage remained childless; Anna died in 1616. His second marriage to Maria Elisabeth von Waldburg zu Zeil had 18 children, of which the son Bonaventura, born in 1619, and his brother Paul, born in 1637, were important for Grönenbach.

Overall, the Fuggers had little luck with their property in Grönenbach, the time of their rule was marked by the Thirty Years' War and the religious disputes between the Catholic and Calvinist Reformed believers. The simultaneous use of the collegiate church, introduced in 1560, was ended with the help of Otto Heinrich Fugger in 1621 by decree of the Prince Abbot of Kempten Johann Eucharius von Wolffurt. In 1628 the plague raged in Grönenbach; According to records in the parish archives, a total of 86 people died in the period from September 18 to Christmas 1628. In the years that followed, there were repeated victims of the plague in Grönenbach, for example the Lutheran preacher Johann Herrmann succumbed to the plague in 1630. In 1632 the Swedes passed through the town on their way from Memmingen . They stormed the High Castle and burned down 35 houses and the hospital church and hospital founded by Ludwig von Rothenstein.

After Otto Heinrich Fugger's death in 1644, the rule of Grönenbach passed to his son Bonaventura Fugger. Due to the ongoing disputes on the spot, he has come across the saying that “he would prefer he never saw Grönenbach”. The Swedes invaded Swabia a second time in 1646, and in the summer or towards the end of 1646 the Swedish Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel moved into quarters at Rothenstein Castle for several months . The effects of the Thirty Years' War and the passage of the Swedes on the population can be seen from the few baptismal records from 1633 onwards. The decline in population was partly offset by foreign immigration, including from other parts of today's Bavaria, Württemberg , Tyrol and Switzerland. Bonaventura moved into the Hohen Schloss zu Grönenbach and began in 1682 together with his brother Paul to expand it on the east side with the so-called Fugger extension. Bonaventura Fugger died in 1693; as early as 1690, his brother Paul had taken over tasks in the Grönenbach estate. In 1690 he put an end to the Zell church dispute in which the Reformed in Zell demanded the right to burial in the Catholic cemetery. From 1686 the Kempten abbot Rupert von Bodman negotiated with Philipp Gustav von Pappenheim about the return of the Grönenbach-Rothenstein fief. The Stühlingen-Fürstenberg sideline made a claim on this, as Maximiliana Maria, the daughter of Maximilian von Pappenheim, was married to Friedrich Rudolf von Fürstenberg. For a payment of 65,000 guilders to the Pappenheimers, the prince abbot could withdraw the fief. The remainder of the transition from Grönenbach to the Prince Abbey of Kempten took place under Count Paul Fugger-Kirchberg-Weißenhorn . The part of the fief that had come to the Fugger through his daughter Anna with the death of Alexander von Pappenheim in 1612 was repurchased in 1695 by the Kempten abbot Rupert von Bodman for a payment of 60,000 guilders. These payments were compensation for the newly acquired and additionally purchased apartments in accordance with a legal decision by Innsbruck legal scholars on May 2, 1690.

Prince Abbey of Kempten (from 1695 to 1803)

After the first part of the Grönenbach-Rothenstein fiefdom moved in in 1692, the Prince Abbot of Kempten, Rupert von Bodman , took possession of the new Grönenbach lordship. On January 1, 1692, the prince abbot moved with a large escort from Kempten to Grönenbach in the collegiate monastery and there he had his new subjects vow of loyalty and obedience the next day. After Grönenbach finally fell back from the Fuggers to the Princely Monastery of Kempten in 1695 , the then Prince Abbot Rupert von Bodman established a maintenance office (district administration) in the High Castle. From this point in time, the rule of Grönenbach and the Prince Abbey of Kempten were once again in one hand. The ministerial court lord Karl Christoph Freiherr von Ulm was sent as the first caretaker. After that there were only aristocratic canons of the prince monastery of Kempten. These all carried the title of provost . Until 1803 these were LJ Baron de Riedheim , Udalricus de Hornstein , Adalbert von Falkenstein, Marianus, Freiherr von Welden , Coelestinus, Freiherr von Berndorf, Maurus Tänzl, Freiherr von Tratzberg and Freiherr von Neuenstein and Baron von Zweyer. Under the last provost, Baron von Zweyer, secularization took place in Grönenbach in 1802.

During the War of the Spanish Succession to succeed the Spanish King Charles II , Grönenbach was captured on October 10, 1703 "by accord" (ie without violence) by the Bavarian-French troops who stormed the High Castle. In 1733 the Lordship of Grönenbach and Rothenstein had goods and rights in 79 localities. The area around Grönenbach was also affected by the War of the Austrian Succession . The French marched through the area around Grönenbach in 1741, 1744 and 1745, the Austrians burdened the population with passages in 1743. The place was able to recover from this relatively quickly; In 1760 there were 134 residential buildings, 20 farms and 64 craftsmen in Grönenbach. In the First Coalition War , the French army penetrated again across the Rhine to southern Germany in 1796 , with new clashes in the area around Grönenbach. Rinderpest was introduced in 1796, which became extinct again in 1797. During the Second Coalition War , Memmingen was occupied by the French general Claude-Jacques Lecourbe , while Dominique Joseph Vandamme advanced to Grönenbach and occupied the imperial magazine near Ittelsburg . The effects of this war can be seen from the death records of the parish Grönenbach. The prince monastery Kempten erected various buildings in the vicinity of the High Castle from 1795 to 1800, including a brewery to supply 3 hosts in Grönenbach and 14 in other places. The desertification , in which 148 farmers participated, took place from 1796.

During the reign of Prince Abbot Castolus Reichlin von Meldegg , secularization took place in the Princely Monastery of Kempten and thus also in Grönenbach . As early as December 2, 1802, Johann Martin Edler was given the power of attorney by Abele as the electoral delegate to draw up an exact inventory of all Kemptic possessions. The entire furnishings of the High Castle were valued at 789 guilders and 38 kroner. On February 25, 1803 the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss was adopted and confirmed on March 24, 1803. The goods of the High Castle, which were inventoried in December 1802, were auctioned on August 16 and 17, 1803 for a sum of 1,559 guilders and 9 kroner. The collegiate monastery was dissolved by a decision of May 14, 1803 and the collegiate church was converted into a parish church. Through the secularization, Grönenbach became Bavarian.

Secularization (1803) until today

After the abolition of all possessions of the Princely Monastery of Kempten, a royal Bavarian district court moved into the buildings of the High Palace in 1804 . It was responsible for 19 communities with over 13,000 people and remained there until it was dissolved or moved to Memmingen in 1878. The district court had its seat in Grönenbach only until 1862. The high palace was sold to court photographer Wilhelm Cronenberg in 1881 . He established a graphic and photographic institute with apprentices and kept the castle in his ownership until 1901. He sold the castle on October 21, 1901 to Dominikusringenisen , who housed a branch of the St. Joseph Congregation he founded. Until the castle was sold to the municipality in 1996, this operated a facility for the disabled. The royal Bavarian general commissioner of the Illerkreis decreed in 1815 that the angle or surrogate schools in the remote settlements (including from 1700 in Hueb and from 1811 in Au ) were dissolved by Grönenbach and only schools in Grönenbach itself and in Ittelsburg and Gmeinschwenden gave. The craft guild and drawing school was located in Grönenbach from 1887 to 1922. From 1825 Michael Weißenbach began breeding silkworms , which by 1836 produced over 40 pounds of silk . In the following years, other authorities and agencies based in Grönebach to: A Post expedition was in 1853 and in 1890 the post office opened in 1886, a forestry office , and in 1896 one was telegraph station established. In the years 1862/1863 the tracks of the Illertalbahn were laid; Because of the resistance of the farmers in Grönenbach and Woringen, it runs around 2 km east of the center through the village of Thal . On January 26, 1838, King Ludwig I of Bavaria approved the municipal coat of arms. It shows a green heraldic shield , with a silver stream meandering from top right to bottom left. The green and white striped municipal flag with the municipal coat of arms was approved on March 9, 1936 by decree of the Reich governor.

The stay of the then 21-year-old Sebastian Kneipp in Grönenbach in 1842 and 1843 was decisive for the further development of the place into a Kneipp spa . He received lessons in Latin from Vicar Merkle . At the location of the former steel yard south of the town hall, a plaque commemorates this stay:

“Sebastian Kneipp 1821–1897, coming from his place of birth Stephansried, found accommodation here in the house of the then mayor Schmid, later a steelworker, in the Spitalhof 1842/43 when he was with chaplain Dr. Merkle received Latin lessons and also did agricultural services for his landlord.

In grateful respect, this memorial plaque is dedicated to the Wörishofen priest doctor who is famous far beyond the borders of his homeland and to his healing teaching on water. "

The development of Grönenbach into a Kneipp spa was promoted by the nearby Bad Clevers . The open air or wild bath has existed since the 16th century. In the immediate vicinity, a Kneipp spa was built as early as 1939, which emerged from the former "Cleverssölde". The further expansion of this Kneipp cure home was interrupted by the Second World War, but was supplemented in 1949 with the establishment of an outpatient bathing department in the still existing Haus des Gastes (formerly Löwenwirt) on the central market square of Grönenbach. It was subsequently by the district Memmingen the Kneippkurheim On Stiftsberg opened, leading to the award of the predicate Kneippkurort led 1954th In the years that followed, further Kneipp facilities were opened, some of which still exist. These were the Mathildenbad in 1956 and the Kneipp cure home Am Schlossberg in 1960. Due to the continuous expansion of the health system and the spa facilities on site, Grönenbach was awarded the title Kneipp spa in 1996; then the place name was changed from April 1, 1997 to Bad Grönenbach. In 2004 Bad Grönenbach received the Premium-Class Kneipp spa certificate from the Association of German Kneipp Spa.

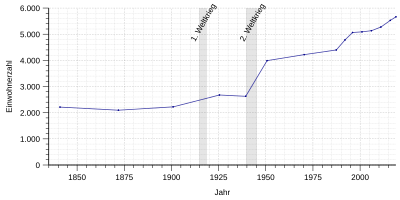

The Russian campaign of 1812 Napoleon demanded 11 victims in Grönenbach. Soldiers from Grönenbach were also involved in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871, 8 of whom died. Towards the end of the war year 1871, Grönenbach had 2094 inhabitants. The First World War claimed 72 dead and missing people from Grönenbach, the Second World War 244. During the Second World War, an auxiliary hospital was set up in the Hohen Schloss and a military service was set up in the now demolished Gasthof Adler. Towards the end of the war (1944), 2648 people, including 623 evacuees and 123 foreigners, lived in the village. In the post-war years, 1000 to 1200 displaced persons were taken in in Grönenbach and Zell. A memorial plaque on the town hall built in 1936/1937 reminds of this. On July 1, 1972, the previously independent municipality of Zell was incorporated. The population growth of the place was, with the exception of a few years, continuously growing, reaching the end of 2018 with 5665 residents all time highs.

literature

- Catholic parish office of St. Philip and James, Grönenbach (ed.): Stiftskirche Grönenbach . 1994, ISBN 3-930102-83-8 .

- Siegfried Kaulfersch: Unterallgäu district . 1st edition. tape 2 . Memminger Zeitung Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, Mindelheim 1987, ISBN 3-9800649-2-1 , p. 1010-1021 .

- Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from taking land on the Ach to a market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975.

- Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954.

- Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910 ( wikisource.org ).

- Hans Schwackenhofer: The Reichserbmarschalls, counts and gentlemen from and to Pappenheim . Walter E. Keller, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-934145-12-4 .

- Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the lordly county of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840 ( digital-sammlungen.de ).

- Royal Bavarian intelligence sheet of the Iller district for the administrative year 1816/1817 . Old town Kempten from Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1817, p. 131–135, 138–141 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation. Ground monuments: D-7-8127-0009, D-7-8127-0010, D-7-8127-0016. (PDF) Retrieved November 22, 2017 .

- ^ Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from the land acquisition on the Ach to the market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975, p. 23 .

- ^ Gerhard Weber: Cambodunum - Kempten. First capital of the Roman province of Raetia? - Special volume Ancient World . Ed .: Gerhard Weber. Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-8053-2691-2 , p. 15-24 .

- ^ Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from the land acquisition on the Ach to the market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975, p. 24, 25 .

- ^ Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation. Ground monument: D-7-8127-0039. (PDF) Retrieved November 22, 2017 .

- ^ Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation. Ground monument: D-7-8127-0020. (PDF) Retrieved November 22, 2017 .

- ^ Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation. Ground monument: D-7-8027-0038. (PDF) Retrieved November 22, 2017 .

- ^ Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from the land acquisition on the Ach to the market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975, p. 27 .

- ↑ Ludwig Mayr: History of the rule Eisenburg . Steinbach near Memmingen 1918, p. 6 ( digitized version on Wikisource ).

- ^ Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from the land acquisition on the Ach to the market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975, p. 30 .

- ↑ JGD Memminger: Württembergische Jahrbücher for patriotic history, geography, statistics and topography . Stuttgart and Tübingen 1835, p. 142 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 14 .

- ↑ RIplus Regg. B Augsburg 1 n.470, in: Regesta Imperii Online. Retrieved November 23, 2017 .

- ^ RI IV, 1,2 n.781, in: Regesta Imperii Online. Retrieved November 23, 2017 .

- ^ A b Franz Ludwig Baumann: Journal of the historical association for Swabia and Neuburg - Necrologia Ottenburana . tape 5 . Augsburg 1878, p. 445 ( full text ).

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 95 .

- ↑ Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 15 .

- ↑ Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 17 .

- ^ D. Franz Dominicus Häberlins: Teutsche Reichs-Geschichte . tape 1 . Hall 1774, S. 378 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 18 .

- ↑ Peter Blickle: Historical Atlas of Bavaria . Ed .: Commission for Bavarian State History. Munich 1967, p. 296 ( online ).

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 133 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 157, 158 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 11 .

- ↑ Peter Blickle: Historical Atlas of Bavaria . Ed .: Commission for Bavarian State History. Munich 1967, p. 297 ( online ).

- ^ A b Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of the county of Kempten from the earliest times up to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 160 .

- ^ Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from the land acquisition on the Ach to the market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975, p. 29 .

- ↑ a b Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 45 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 237 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 238 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 239 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 294 .

- ↑ a b Unterallgäu district . 1st edition. tape 2 . Memminger Zeitung Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, Mindelheim 1987, ISBN 3-9800649-2-1 , p. 1010 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 372 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 14 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 374 .

- ^ A b Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of the county of Kempten from the earliest times up to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 444 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 446 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 445 .

- ^ Georg Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments - Bavaria III - Swabia. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 2008, p. 166 .

- ^ Hans Schwackenhofer: The Reichserbmarschalls, counts and gentlemen from and to Pappenheim . Walter E. Keller, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-934145-12-4 , pp. 152, 153 .

- ↑ M. Johann Alexander Döderlein: Historical news of the very old high-priced house of the imperial and the empire marshals of Palatine, and the married and dermahligen imperial hereditary marshals, lords and counts of Pappenheim, etc. Johann Jacob Enderes , Hoch-Fürstl. privil. Book dealer, 1739, p. 232 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 22 .

- ^ Hans Schwackenhofer: The Reichserbmarschalls, counts and gentlemen from and to Pappenheim . Walter E. Keller, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-934145-12-4 , pp. 153 .

- ↑ a b Unterallgäu district . 1st edition. tape 2 . Memminger Zeitung Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, Mindelheim 1987, ISBN 3-9800649-2-1 , p. 1011 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 18 .

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 475 .

- ^ A b Hans Schwackenhofer: The Reichserbmarschalls, counts and lords from and to Pappenheim . Walter E. Keller, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-934145-12-4 , pp. 154 .

- ^ Franz Ludwig Baumann: History of the Allgäu, from the oldest times to the beginning of the nineteenth century . tape 2 . Kempten 1883, p. 648 ( full text ).

- ^ Hans Schwackenhofer: The Reichserbmarschalls, counts and gentlemen from and to Pappenheim . Walter E. Keller, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-934145-12-4 , pp. 155 .

- ^ A b Hans Schwackenhofer: The Reichserbmarschalls, counts and lords from and to Pappenheim . Walter E. Keller, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-934145-12-4 , pp. 158 .

- ↑ a b Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 38 .

- ↑ Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 58 .

- ↑ Otto Erhard: Kempter Reformation History - The Reformation of the Church in Kempten . Printed and published by Tobias Dannheimer, Kempten 1917, p. 23, 24 .

- ^ Hans Schwackenhofer: The Reichserbmarschalls, counts and gentlemen from and to Pappenheim . Walter E. Keller, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-934145-12-4 , pp. 161 .

- ^ Hans Schwackenhofer: The Reichserbmarschalls, counts and gentlemen from and to Pappenheim . Walter E. Keller, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-934145-12-4 , pp. 162, 167 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 25 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 27 .

- ↑ Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 42 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 137 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 47 .

- ↑ Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 43 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 120 .

- ^ Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from the land acquisition on the Ach to the market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975, p. 24 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 249 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 142-144 .

- ^ Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from the land acquisition on the Ach to the market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975, p. 32 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 130 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 99 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 172 .

- ↑ Dr. Eduard Wehle: History of the small German courts . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1860, p. 172 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ↑ The most valuable Swabian Circle's complete state and address book to the year 1777 . Ulm 1777, p. 29 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Johann Baptist Haggenmüller: History of the city and the princes of Kempten from the earliest times to their union with the Bavarian state . Tobias Daunheimer, Kempten 1840, p. 274 .

- ↑ Gottlieb Schumann: European Genealogical Handbook . Johann Friedrich Gleditschen's story, Leipzig 1756, p. 203 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ↑ New genealogical-schematic Reichs- und Staats-Handbuch before 1760 . Franz Barrentrapp, Frankfurt am Main 1760, p. 188 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ^ M. Christian Friedrich Jacobi: European Genealogical Handbook on the year 1800 . Johann Friedrich Gleditschen's story, Leipzig 1800, p. 292 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Supplements to the minutes of the extraordinary Reich Deputation in Regensburg . Konrad Neubauer, Regensburg 1803, p. 89 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 214 .

- ↑ Hans Schulz, Otto Basler, Gerhard Strauss: German Foreign Dictionary: a-prefix-antike . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1995, pp. 261 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 145 .

- ↑ Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 44 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 146 .

- ↑ a b c Unterallgäu district . 1st edition. tape 2 . Memminger Zeitung Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, Mindelheim 1987, ISBN 3-9800649-2-1 , p. 1012 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 148 .

- ↑ a b Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 149 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 181-183 .

- ^ Karl Schnieringer: Grönenbach - Its development from the land acquisition on the Ach to the market and Kneipp spa . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1975, p. 26 .

- ^ Joseph Sedelmayer: History of the market town Grönenbach . Ed .: Historical association for the overall promotion of local history of the Allgäu. Jos. Kösel'schen Buchhandlung in Kempten, Kempten 1910, p. 253 .

- ↑ Klemens Stadler, Friedrich Zollhoefer: Coat of arms of the Swabian communities (= Swabian local history . Volume 7 ). Verlag des Heimatpflegers von Schwaben, Kempten 1952, p. 150 .

- ↑ Luitpold Dorn: Grönenbach - A guide through the place and its history . Kurverwaltung Grönenbach, Grönenbach 1954, p. 16 .

- ↑ Unterallgäu district . 1st edition. tape 2 . Memminger Zeitung Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, Mindelheim 1987, ISBN 3-9800649-2-1 , p. 1013 .

- ^ Sigrid Losert: Bad Grönenbach 1099-1999; From the wild bath to the medicinal bath . Ed .: Bad Grönenbach spa administration. Bad Grönenbach 1999, p. 7, 8 .

- ↑ kurorte-und-heilbäder.de: Bad Grönenbach , accessed on March 3, 2018

- ↑ a b Bavarian State Office for Statistics (ed.): Statistics communal 2017 - Markt Bad Grönenbach 09 778 44 - A selection of important statistical data . Fürth 2018, p. 6 ( bayern.de [PDF]).

- ^ Wilhelm Volkert (ed.): Handbook of Bavarian offices, communities and courts 1799–1980 . CH Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-406-09669-7 , p. 521 .

- Extract from documents from the Bavarian State Archives :

- ↑ Document on the foundation of the grand and minor tenth in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten, archive documents 225), 1405, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration signature: XLVIII lit. D n.17

- ↑ deed of Marshal main cardboard home and his wife Corona by Rothstein Thomas and Ludwig by Rothstein in the state archives Augsburg (StAA, Prince pin Kempten, Archival records 262), 1412, Origin: Prince pin Kempten, archive, registration signature: XIX Lit. D n. 29

- ↑ Confirmation of the payment of 2000 florins from Thomas and Ludwig to Haupt von Pappenheim and Corona von Rothenstein in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten documents 6317), 1413, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration signature: box: 176; Drawer: E; Number 1; Additional: 02, old archival signature: BayHStA, Mediatized Princes, Pappenheim 22

- ^ Document on the division of the estate of Thomas and Ludwig von Rothenstein in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten Urkunden 6324), 1440, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration signature: CLXXVIII Lit. D No. 21 Archival old signature: BayHStA, Personenselect Cart. 357

- ↑ Letter of foundation for the eternal mass in Grönenbach in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten, archive documents 929), 1471, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration signature: XLVIII lit. D n. 18

- ↑ Document confirming the confirmation of the collegiate foundation in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten, Archiv Urkunden 1112), 1479, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration signature: XLVIII lit. D n. 1

- ↑ Copy of Ludwig von Rothenstein's will in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten, archive files 1266), (1479) 1686, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration signature: No. XLVIII Lit. D No. 2, old archival signature: BayHStA, Fürststift Kempten / NA, A 0387/1

- ↑ register of the feudal succession dispute between Heinrich von Rothstein and marshals of Pappenheim in the State Archives Augsburg (StAA, Imperial Abbey of Kempten, archive volumes 532), 1485, provenance: Imperial Abbey of Kempten, archive, filing Signature: No. LIX lit. D no. 1, old archival signature: BayHStA, Fürststift Kempten / MüB 280

- ^ Document on the disputes between the Pappenheimers and Rothensteiners zum Falken in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten, archive files 3543), 1484–1514, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration number: No. CLXXVI Lit. D n. 1, old archival signature: BayHStA, Mediatisierte Fürsten, Pappenheim 26 I.

- ^ Document on the handover of Rothenstein Castle to Wilhelm and Gangolf in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten Urkunden 6370), 1508, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registry signature: box: 176; Drawer: D; Number 1; Additional: 2, old archival signature: BayHStA, Mediatisierte Fürsten, Pappenheim 26 I.

- ^ Documents, the appointment of Baroness Anna von Rechberg zu Hohenrechberg, born von Pappenheim, as co-owner and heiress of the Grönenbach rule through her father, Reichshermarschall Alexander von Pappenheim in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten, archive documents 4823, 4869, 4871), 1609, 1612, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration signature: CLXXVI lit. F n.9

- ↑ Legal opinion of the University of Innsbruck on the leasability of the Lordship of Grönenbach in the Augsburg State Archives (StAA, Fürststift Kempten, archive volumes 493), 1690, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration signature: No. XLVIII Lit. D n.32, old archive signature: BayHStA, Fürststift Kempten / NA, A 0411

- ↑ Taking possession of the Grönenbach rulership and paying homage to the subjects there in the Augsburg State Archive (StAA, Fürststift Kempten, archive files 609), 1693, provenance: Fürststift Kempten, archive, registration number: No. XIX lit. A n. 5, old archival signature: BayHStA, Fürststift Kempten / NA, A 0385