History of the railroad in Austria

The history of the railways in Austria presented here includes Old Austria until 1918 without the countries of the Hungarian crown , which belonged to the Austrian Empire until 1867, and also without Bosnia-Herzegovina, which was occupied by Austria-Hungary in 1878 and annexed in 1908 . From November 1918 it refers to what is now the territory of the Republic of Austria including Burgenland, which was not joined until 1921 .

First private railways (1824–1841)

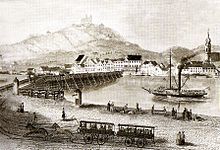

First horse-drawn railway : Linz – Budweis

Canal or Railway?

The country of origin of the Austrian railways is Bohemia : In 1808 Franz Josef von Gerstner gave a remarkable speech to the “ Bohemian Hydrotechnical Society ” in Prague , in which he advocated the construction of a railway and not a canal between the Vltava and Danube . (Even then it was about the modernization of the salt transport from the Salzkammergut to Bohemia.) In connection with the " Dresden Elbe Conference" (1819 f.) - where, among other things, the "Free ride from Prague to the sea ( North Sea )" was agreed - the problem of the connection between the Vltava and the Danube reappeared: it should be solved by a canal or a railway. For technical and economic reasons, Austria opted for the railway variant.

Gerstner himself already felt too old to play a bigger role in the realization of the project. His son Franz Anton von Gerstner , professor in Vienna , welcomed the progressive attitude at court and devoted himself intensively to the railway project. In 1822 he visited England , the "motherland of the railways". Since there was a considerable difference in altitude between Moldau ( Budweis ) and Danube, Gerstner junior was interested. especially for how to overcome altitude differences in England. The local method of using " inclined planes " ( steep stretches ), over which entire trains were carried by the cable of a stationary steam engine, he did not consider imitable.

Gerstner jun. claimed that it was possible to lay a “continuous rail line through the mountains” if only the necessary dams and incisions were made. This would make the “inclined planes” completely obsolete. In England his thoughts initially met with little approval, but they soon spread worldwide. The overcoming of the Semmering in Austria in 1854 ("First high mountain railway in the world") by Carl Ritter von Ghega goes back to Gerstner's basic idea.

Horses or steam locomotives ?

With Gerstner Juniors railway construction began in 1824 the "first private railway phase" in Austria; his elderly father served as a consultant. In 1825 the groundbreaking ceremony for the “Budweis-Danube Railway” took place in Netrowitz near Kaplitz ( Bohemia ). The corresponding railway company called itself just " kk priv. First railway company ". It was the first railway company in the German-speaking area. By 1827 Gerstner's mountain road over the Kerschbaumer Sattel (Upper Austria / Bohemia border area) had been completed, in a form suitable for locomotives. Because Gerstner jun. had already shown the steam company great sympathy on his trip to England in 1822 and viewed it as a future perspective. In the course of another trip (1826/27) this sympathy was nourished even further.

Inflation put the company in trouble; Intrigues caused Gerstner junior to leave the construction site in 1828. His successor, Mathias von Schönerer , remained fundamentally true to Gerstner's building principles, but disregarded his requirement to create gentle slopes (max. 11 per thousand). In the Kerschbaum-Lest area, in order to save money, there were steep ramps (21 per thousand) and tight curves. In Schonerer's time it was also decided not to run the train to Mauthausen , but to Urfahr , the suburb of Linz on the other bank of the Danube.

The Budweis – Linz – Gmunden horse-drawn railway was opened in 1832. In terms of technology history, it does not represent a particularly great success. In view of the cost-cutting measures after Gerstner Juniors' departure, the southern part of the line could not later be converted to steam operation. But these steep ramps were also unfavorable for the horse business, as the trains had to be divided before overcoming them. But since the transport worked - in addition to salt, many other goods were transported very soon - the company was an economic success.

In 1836 the extension to the “Bürgerliche Salzaufschütt” in Gmunden on the Traunsee was put into operation, also in this section with a steep ramp of over 30 per thousand, over which the wagons had to be pulled up individually. Since the section Linz Südbahnhof – Gmunden Traundorf had no other problems whatsoever, steam operation could be introduced for passenger traffic in 1855/56. From Linz to Budweis, the Gerstner route was abandoned from 1869 to 1872 and the new route for steam locomotives swiveled to the west. Isolated remains have been preserved to the present day and are reminiscent of the old route.

The failure Prague – Lana

While the Budweis – Danube railway project was opened and functioned despite all the technical deficiencies, this was not the case with the Prague – Lana horse-drawn railway . In 1828 the route was started as the Prague-Pilsen Railway . But in 1831 construction ended in the Fürstenberg Forest (part of the Pürglitzer Forest ) in the Lana area . In addition, the railway could not be put into operation due to technical defects. Fürstenberg finally bought the line and made it operational by 1838. Then it was used as a forest railway from the bank of the Klíčava brook to Prague . It was economically unfavorable that the trains from Prague always had to return empty to the forest, as there was no demand for transport in this direction. Ultimately, the railway was part of the Buschtěhrad Railway and was dismantled. Some remains still exist today.

First steam train: The Northern Railway

The groundbreaking ceremony for the Emperor Ferdinand's Northern Railway, which opened in 1838, is considered to be the “birth of the railway” (with locomotive operation) in Austria. This project developed into a true success story: up to the nationalization in 1906, the economically highly successful Nordbahn-Gesellschaft built a very extensive network. The northern railway became the most important railway line of the Habsburg monarchy .

Temporary end of private investments

The first Austrian private railway phase ended against the background of the following facts:

- Since 1837 the state has been firmly convinced of the great importance of the railway system (economy, society, warfare) (documented in cabinet letters).

- From their profit-oriented point of view, the private capitalists began to doubt the future potential of the railways.

- Thus, the expansion of the railway network seemed to come to a standstill. In order to counteract this, the state took the railroad issue into its own hands and initiated the “First State Railroad Phase” at the end of 1841.

The first state railway phase (1841-1854/58)

Railway program of the Imperial and Royal Government

The state's railway program provided for the construction of several important lines. The centerpiece was the northern runway from Vienna to the north and a southern runway from Vienna to the Adriatic port of Trieste and to Lombardy-Venetia . The aim was also to complete the Venice-Milan railway, which began under private aegis . State railroad construction began there in 1852.

By 1851 the northern line to Bernhardsthal was completed. From the railway station Olomouc the direction of Krakow 's leading Emperor Ferdinand Northern Railway , the route via Prague became the northern border at Bodenbach out where the connection to the Saxon railway network took place. A branch of this line led to Brno .

In 1857 the southern railway Vienna – Trieste was opened, which includes the demanding Semmering line from Gloggnitz to Mürzzuschlag . This was the first high-mountain railway in the world to be opened to traffic in 1854. Between Graz and Trieste, the Ljubljana Moor had to be overcome by backfilling and the Karst by means of a mountain road. The establishment of the militarily important railway connection to Lombardy-Veneto did not take place. It should have started in Aurisina north of Trieste; when Lombardy was lost to Austria in 1859 , this connection was obsolete.

The effect of the southern runway on the port of Trieste remained modest for the time being, as most of the port facilities came from the 18th century and the newly built "railway port" was much too small. The Südbahn was operated by the Südbahngesellschaft until 1923 .

On the other hand, the project of a western railway was treated half-heartedly . One could not get beyond the alignment of 1842 ( Friedrich Schnirch ). This was despite the fact that Bavaria had already made a clear appeal to Austria in 1838 to establish a rail link.

End of state investment

The state railway construction was exemplary in both technical and operational terms. However, since the state suffered from a severe lack of funds, it was unable to continue this railway policy.

When Trieste was opened up in 1857, the “state railway phase” was officially long since officially over. As early as 1854, with the enactment of the “New Concession Act”, the “Second Private Railway Phase” was legally established. Unfinished state railways, such as Vienna – Trieste, were completed in the period that followed. The transfer of the state railway network (and state railway projects) into private hands also lasted beyond 1854. This process could not be completed until 1858.

The second private railway phase (1854 / 58–1873 / 80)

The concession law of 1854 mentioned above was the backbone of the second private railway phase in Austria. This should above all railroad-like wild growth such. B. be prevented in the USA. In the course of the concession procedure, the concession applicant had to disclose all aspects of his project (especially with regard to function, financial resources) and only after carefully examining these facts did the state grant permission to build the railway.

Overall, the Austrian railway construction lagged behind that of other European countries and especially behind that of Prussia . During the German War in 1866, Commander-in-Chief Ludwig von Benedek found himself unable to deploy troops to the Bohemian theater of war that were no longer needed after the brilliant victory in the Battle of Custozza in Italy : the railway was simply unable to cope with this task. This is seen as one of the reasons Austria lost the war.

Incentives for private investors

The state now promoted private railway companies on a sustainable basis: on the one hand, they got cheap loans, on the other hand, interest guarantees. The railway sector became interesting again for private investors.

Although the state had stopped building the railway due to a lack of money, it was in a position to grant railway loans, although the economic situation was generally perceived as precarious. If the direct expenditures of the state for the railway construction meant expenditure or the change from liquid funds to illiquid fixed assets, the given loans could be booked as lent liquid state capital.

Overall, the second private railroad phase brought extensive network growth with it. However, private companies simply did not tackle economically viable projects: They were too risky, too expensive or too little profit-oriented for private investors. These privately not built routes included, for example:

- Arlbergbahn (it should have served, among other things, the connection from Switzerland to Trieste)

- (Vienna–) Divača - Pola (the crossing of Istria from Trieste to the Austrian main war port Pola)

- Dalmatian Coastal Railway ( Dalmatia was surrounded by territory of the Hungarian half of the empire since 1867 ; the war ports of Šibenik and Kotor were located in Dalmatia )

It was thanks to the Minister of Commerce, Bernhard von Wüllerstorf-Urbair , that in 1866 he presented a future-oriented railway memorandum in which he implicitly called for state involvement.

The settlement with Hungary in 1867 made the two halves of the empire of the new dual monarchy politically independent of each other. They were now pursuing different objectives in terms of rail policy, but had agreed on the same approach to rail law and technical rail standards (not constitutionally mandatory). Numerous plans and regulations were therefore agreed verbatim from 1868 on between the Austrian and Hungarian ministers responsible for railways before they were decided separately by the two parliaments. Since foreign policy was one of the tasks that the monarch constitutionally designed uniformly for the entire monarchy, international railway agreements were concluded on behalf of the emperor and king for all of Austria-Hungary.

New government investment

The economic crisis that began in 1873 triggered a rethink and the state began to become directly involved again. On the one hand, he provided massive financial support to private companies, on the other hand, he again built state railways on his own. In 1876, for example, the Pola naval port was finally connected to the center of the state. This Imperial and Royal State Railroad was initially operated by the Südbahngesellschaft.

In 1880, the Reichsrat unanimously approved the funding for the construction of the Arlberg tunnel . This marks the entry into the "second state railway phase". As a result, the “state railroad idea”, like in many other European states, especially in the German Reich, gained more and more power, ultimately nourished by the economic upswing at the turn of the century.

The Imperial and Royal State Railways and the Southern Railway Company (1880–1918)

The railway agendas in the Cisleithan state were taken care of by the Imperial and Royal Ministry of Commerce from 1867 . In line with the greatly increased importance of the railway, the Imperial and Royal Railway Ministry was founded in 1896 , which existed until November 1918 and continued the offensive policy for the state railway as the most important means of transport in the country (see transport policy ). The emperor mostly appointed qualified railway experts as ministers.

nationalization

The nationalization of railways, then called redemption (taking over the shares at a certain price) or acquisition, created a sizeable state rail network, but remained incomplete in the monarchy. Numerous loss-making private railway companies were nationalized - for example B. 1884 the Kaiserin-Elisabeth-Bahn (the Westbahn) and 1887 the Rudolfsbahn - but the important Southern Railway Company remained private until 1923.

The state could not directly use this "deficit colossus" in its railway policy and initially decided in 1906 to nationalize the wealthy Emperor Ferdinand's Northern Railway , the most important railway in the monarchy. This decision turned out to be quite lucrative due to the very extensive coal transports on this railway, but it brought with it short-term problems: After the northern railway shareholders learned of the intention to nationalize, they reduced the maintenance work for the railway network and vehicles to almost zero. A "transport crisis" was the result; but this could be fixed quickly.

New alpine railways

In 1901 the Austrian state decided to make investments of historical importance: by building several large alpine railways, the " Trieste crisis" (basically since 1850) was finally to be overcome in a sustainable manner. The modern port expansion had already started in 1867. The decision made in 1901 by the Reichsrat , the parliament of Old Austria, concerned the largest investment project of the last decades of the monarchy with a volume equivalent to 1.76 billion euros (for details see political mandate ).

These "New Alpine Railways" (the political term), meaning the Tauernbahn , the Pyhrnbahn , the Karawankenbahn and the Wocheiner Bahn (including the Karstbahn), differed from the Semmering Railway, which opened in 1854, in terms of construction: Based on the model of the Franco-Italian, The 12.2 km long “ Fréjus Tunnels ” (built 1857–1871 as part of the Mont-Cenis Railway ) were now tunneled under significant Alpine crossings in several places over longer distances.

In Austria this method was used for the first time in the 10.6 km long Arlberg tunnel . Particularly during the construction of the Bosruck Tunnel and the Wocheiner Tunnel , extensive problems with rock formations and water ingress had to be struggled with. It was not until 1909 that this large company was successfully completed with the opening of the Tauern Railway . In Trieste and Gorizia , the connection from Salzburg via the Tauern, Karawanken and Wocheiner Bahn is still called “La Transalpina” today.

Importance of the railroad

At that time, the railway was an indispensable part of political, economic and social life. It performed functions that other modes of transport (truck, car, airplane) also fulfill today .

- The post in Austria-Hungary was carried by rail mail over longer distances .

- Ruling Austria-Hungary for weeks in the summer from Bad Ischl , the emperor's summer residence, was only possible because politicians advising the emperor could travel by train at short notice. From Prague there were e.g. B. own through coaches to "Išl"; the Czech spelling on bilingual target boards even gave rise to German national protests.

- Location decisions for heavy industry companies were influenced by rail connections, for example the iron industry on the Northern Railway in Moravia . Regions away from the railways fought for a connection to the rail network in order to be able to participate in industrialization .

- State visits were made by train: Kaiser Wilhelm II came with his court train and got off at the Wien-Penzing station when he visited Franz Joseph I in 1908 for his 60th anniversary on the throne in Schönbrunn Palace .

- Early tourism developments , such as on the Semmering , in the Salzkammergut , in southern Tyrol and in Istria, can be traced back directly to rail connections from metropolitan areas.

- Transports of troops and weapons to deployment or defense areas in World War I and transports of the wounded from the front to the hospitals in the hinterland were carried out exclusively by rail. Army field railways were built and operated in many places between regular railway lines and the front . Huge quantities of supplies (ammunition, weapons, soldiers, etc.) were transported to the fronts for the material battles.

- Large events such as the World Exhibition in Vienna in 1873 ( Wiener Prater ) - 7,255,000 visitors and over 50,000 exhibitors came in six months - were hardly conceivable without a rail connection.

- When Old Austria disintegrated in 1918, there was a dispute between the successor states Czechoslovakia , German Austria and the SHS state over the division of the rolling stock of the kk state railways, especially the locomotives (more details here )

As of 1918

In 1918, the old Austrian network essentially had a fan-shaped structure. The most important node was the capital Vienna. With the exception of the Vienna – Split connection (under construction in 1918), the following main connections were established:

- the Northern Railway from Vienna via Lundenburg (Breclav) to Brno and Prague (with a connection to Berlin ) or to Krakow , Lemberg and Chernivtsi ,

- the southern railway from Vienna via Graz and Steinbrück to Ljubljana and Trieste or to Agram and Belgrade ,

- the Western Railway from Vienna via Wels to Salzburg (connection to Munich ), Innsbruck and Bregenz (connection to Switzerland ) or to Passau (connection to Frankfurt am Main ),

- the Eastern Railway ( Marchegger Ast) from Vienna to Pressburg and Budapest ,

- the Vienna-Raaber Bahn (today Ostbahn, eastern branch) from Vienna via Bruck an der Leitha to Raab and Budapest (connection to Belgrade and Transylvania ),

- the Kaiser-Franz-Josephs-Bahn from Vienna via Gmünd and Budweis to Prague,

- the Eastern Railway (northern branch) from Vienna via Laa an der Thaya to Brno,

- the Tauernbahn from Salzburg to Villach , through the Karawanken tunnel to Laibach or via the Wocheiner Bahn to Gorizia and Trieste.

There were numerous cross connections between these main lines (e.g. Linz - Selzthal - St. Michael and Gänserndorf - Marchegg ).

The Austrian Federal Railways (1918–1938)

Since the Swiss Oensingen-Balsthal-Bahn officially used the abbreviation OeBB, the Austrian Federal Railways , 1918/19 German-Austrian State Railways, 1919/20 Austrian State Railways, had to be abbreviated as "BBÖ" in the interwar period; the inscriptions on the vehicles were analogous to “Federal Railways Austria”. However, in 1922 there were still wagons in circulation with a wide variety of names: “Ö. St. B. "," B. B. Austria O "," B. B. Austria ”and a subsequent equilateral triangle, the point of which pointed to the lettering, as well as wagons that still bore the traditional names from the time of the monarchy.

Consequences of the disintegration of Old Austria

The former “loaf of the state” of Bohemia and Moravia with dense, profitable rail traffic, was now abroad. Austria remained the Alpine routes with high operational and maintenance costs and comparatively significantly less traffic, depending on coal imports from Czechoslovakia.

Since the Unterdrauburg railway junction in Carinthia fell to Yugoslavia in 1918/19, the connection from the Lavant valley to the state capital Klagenfurt was only possible from abroad. The Jauntalbahn was only created as a domestic connection in 1963 . Similarly, East Tyrol from North Tyrol by the 1918/1919 Italy annexed South Tyrol reach.

The Moravian railway connection Nikolsburg - Lundenburg ran near Feldsberg over Lower Austria. The city therefore had to be ceded to Czechoslovakia in the 1919 Treaty of Saint-Germain ; the latter had rejected the proposal to rebuild the section at the expense of Austria on Moravian territory.

The Bohemian railway lines from Pilsen via Budweis and from Prague via Tábor to Vienna united in Gmünd (Lower Austria) . The main train station including workshops (Gmünd III district, now České Velenice ) and the villages on the two routes had to be ceded to Czechoslovakia in 1919.

The railway line Deutschkreutz - Rattersdorf -Liebing in central Burgenland was connected to northern Burgenland from 1921 via Ödenburg , which remained Hungarian .

The southern railway , until then operated by the private southern railway company, was divided into private railway companies in the successor states of the monarchy in 1918 and taken over by the state in Austria in 1923. From 1924 it was run by the Federal Railways.

Electrification program

The "electrification program" that had already been drawn up during the monarchy was implemented from the 1920s. The following major lines were electrified in the interwar period :

- Innsbruck West – Telfs-Pfaffenhofen – Landeck (1923)

- Stainach-Irdning-Attnang-Puchheim (1924)

- St. Anton am Arlberg – Langen am Arlberg (1924)

- Landeck-St. Anton am Arlberg (1925)

- Langen am Arlberg – Bludenz (1925)

- Bludenz – Feldkirch – State border near Buchs (1926)

- Feldkirch – Bregenz (1927)

- Innsbruck – Wörgl – state border near Kufstein (1927)

- Wörgl – Saalfelden (1928)

- Innsbruck – Brennersee (1928)

- Salzburg – Schwarzach-St. Vitus (1929)

- Schwarzach-St. Veit – Saalfelden (1930)

- Schwarzach-St. Veit Mallnitz (1933)

- Brennersee - State border near the Brenner (1934)

- Mallnitz – Spittal-Millstättersee (1935)

The railroad in politics

In 1933 the Federal Railways were connected to a momentous event in Austrian politics. After a railroad strike, there was a dispute in the National Council about what impact the strike should have on the salaries of railroad workers. The Conservative Dollfuss government, which was ready for dictatorship, took advantage of a crisis of rules of procedure, which it called parliamentary self-elimination , to govern without parliament after March 4, 1933. This marked the path of the country into the corporate state .

The Reichsbahn era (1938–1945)

After the "Anschluss" of Austria by the German Reich on 12./13. On March 18, 1938, the Federal Railways were incorporated into the Deutsche Reichsbahn . The armament of the Wehrmacht , which had been going on for years in the German Reich , was extended to the "Ostmark" (from 1942: " Donau- und Alpenreichsgaue "); with the smashing of the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 also the rest of Czechoslovakia .

The rail network in Austria was mainly adapted to military transport needs: the capacity of the Tauernbahn was massively increased, and the line from Passau to Wels to the Westbahn was expanded to two tracks.

From March 1938 the train served many Austrians to flee abroad (some of them have incorporated this train journey into their memories; see literature). From 1942 the train was used to deport Jewish citizens . Deportation trains were dispatched in Vienna in the Aspangbahnhof and in the Nordbahnhof . Among other things, they drove to Mauthausen concentration camp .

As in the First World War, troops and weapons were transported over greater distances by rail whenever possible.

In 1944/45 the railroad facilities, especially in eastern Austria , were bombed by the Allies (mainly to disrupt or stop the enemy’s supplies and troop movements); many tracks, bridges, vehicles and railway buildings were damaged or destroyed.

On the occasion of its 175th anniversary in 2012, the ÖBB sheds light on its history from 1938 to 1945 for the first time with an exhibition. Among other things, she writes:

“From March 1938, the National Socialist rulers tried to bind the railway employees to their regime. Railway workers had to follow stricter rules than civil servants, had to "stand up for the National Socialist state at all times" and they were subjected to a comprehensive political investigation and surveillance. Nevertheless, they were significantly involved in the resistance against National Socialism. The Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) reported in 1941 about the resistance at the railways that, compared to the "Old Reich ...... the Ostmark since the outbreak of the war in 1939 played a greater role in terms of sabotage police, since the foreign intelligence services and the domestic opponent groups already did it earlier." understood how to set up sabotage organizations…. "154 railway employees were sentenced to death and executed for their resistance, 135 died in concentration camps or prisons, 1,438 were sentenced to concentration camp or prison terms."

The Austrian Federal Railways and other railways (1945 to today)

The current rail network in Austria is documented here:

post war period

In the immediate post-war period, the focus in eastern Austria was on repairing war damage. The reconstruction of the Vienna railway stations was given a special symbolic content, but it was not possible to bring about more far-reaching structural changes in the Vienna railway network and therefore they were rebuilt as terminal stations at their original location.

The vehicle fleet was severely decimated and for a long time still badly marked by the war; even the oldest vehicles were subjected to extreme stress. In 1951 there was a serious train accident in Langenwang (Styria) with 21 dead, which was also due to the destruction of a car with a wooden box from 1907. In the years that were wooden car bodies continuously dismantled and rebuilt on the undercarriages steel boxes in unit construction, these so-called Spantenwagen were isolated until the 1990s in use.

Heading from the west and south of the country towards Vienna, the electrification of the main lines was completed; the biggest surge took place in the 1970s. At the same time, the railway lost its importance as a means of transport from the 1960s onwards with increasing motorization . Branch lines and local railways were partially discontinued, symbolized for the public by the discontinuation of the Salzkammergut local railway in 1957. The conversion from steam traction to electric and diesel operation was completed by 1976, steam locomotives were only to be found for a longer period of time on the rack railways and some narrow-gauge railways.

At the iron curtain

During the time of the Iron Curtain , the flow of traffic changed more sustainably than after 1918. Although there were trade relations with the “East”, the existing rail connections were overdimensioned. Therefore, mostly only one track was kept in operation across the state border, even on double-track lines. On the Marchegg branch of the Ostbahn from Vienna Stadlau to Marchegg , the full length of the second track was removed. (It is currently being rebuilt.) On the Pressburger Bahn , a local railway on the southern bank of the Danube, which connected the city centers of Pressburg (Bratislava) and Vienna, cross-border traffic was discontinued in 1945 and has not been resumed to this day. The traffic on the northern branch of the Eastern Railway from the border station Laa an der Thaya to the Czech Republic has not been operated again since 1945. The Fratres - Slavonice (Zlabings) connection in the Lower Austrian Waldviertel has also been interrupted since then, although the restoration was sought several times after 1991. In contrast, the cross-border routes of the Raab-Oedenburg-Ebenfurter Eisenbahn , a Hungarian-Austrian joint venture, could always be used, as did the railways to Yugoslavia (with the exception of the Radkersburg - Oberradkersburg connection ).

Old traffic routes were also bypassed: traffic from Vienna to Hamburg no longer ran via Prague , but via Passau . It was also preferred to travel to Berlin from Vienna via " West Germany " instead of the direct route via Prague. Instead of using the previously usual connection Prague- Budweis- Trieste through Austria, the Czechoslovak trains in the direction of the Adriatic were now led via Pressburg , Hungary and Yugoslavia . The Tauern Railway gained enormous importance as a connection, especially for guest worker traffic with trains such as the Tauern Express and the Istanbul Express between Central Europe and the Balkans, not least because the old Orient Express route via Bratislava and Budapest with visa requirements and complex Border and currency controls have lost a lot of demand.

After 1989, rail traffic across the eastern Austrian borders could be increased again. In 2009 there were significantly more trains per day from Vienna to the Slovak capital Pressburg than to Germany and Switzerland.

Transport policy

The federal transport policy on rail transport has been inconsistent since 1945. The railway was and is regarded as an important bastion of social democracy. The flexibilisation of the salary and pension regulations criticized as "ÖBB privileges", advantageous for railway staff and expensive for ÖBB, has not yet been completed. The railway deficit is financed from the state treasury, politics has a considerable influence on the management of the ÖBB. On the other hand, compared to Switzerland , the state is doing little to strengthen the railways. The enormous increase in individual traffic is seen as inevitable. However, there was considerable investment in rail projects from around the mid-1990s. Of course, these expensive extensions do not automatically mean an improvement in the general quality of rail traffic. As the only Austrian party, "The Greens" have been advocating the expansion of public rail transport for decades. The federal railways themselves strive to increase their efficiency through cooperation with neighboring railways ( DB , MAV ). ÖBB routes are now also used by trains from other railway companies on their own account (examples: Westbahn freight trains of the Raab-Oedenburg-Ebenfurter Eisenbahn ).

Future prospects

Later than in many other European countries, the state has given the green light for the expansion of railway lines throughout Austria and for the renovation of important station buildings in recent years:

Local railways

Local railways are railway lines that branch off from main lines and are technically more simply equipped for economic reasons, e.g. B. with narrower, therefore slower to negotiate curves, often with tracks in narrow gauge instead of standard gauge and mostly only single-track.

Local Railway Act (1880)

The narrow-gauge Lambach – Gmundener Bahn is to be seen as the forerunner of later local railways . It has been connected to the Western Railway in Lambach since 1860, but was not built as a local railway, but represents a remnant of the network of the "First Railway Company". Later it was referred to as the local railway.

On May 25, 1880, the Reichsrat passed the originally limited local railway law for Cisleithanien . (The time limit was extended several times.) The law enabled a number of simplifications and simplifications of a technical, operational and administrative nature for the construction and operation of railways off the main routes. More laws of this kind followed. If local railways should be operated by state-owned companies, state laws were passed, e.g. B. in Lower Austria and in Styria ( Niederösterreichische and Steiermärkische Landesbahnen ).

In principle, the local railroad sector was fed by private capital. The first concession was awarded in 1880 for the Hullein - Kremsier line (approx. 6 km) in Moravia. However, the construction of the railway was delayed. The Linz – Kremsmünster line (approx. 36 km), opened in 1881, actually became Austria's first local railway.

Development problems

Conflicts and a lack of cooperation between private railway companies often prevented effective use of the existing local railway infrastructure. For example, the relatively short Wels – Steyr connection in Upper Austria was operated by three railway companies.

Only in Bohemia and Moravia, the technically and economically most highly developed crown lands of the monarchy, could the local railway system develop well. Companies in crisis regions (Alps, Istria, etc.) always struggled to raise building capital and guarantee operations.

The more widespread use of trucks and buses from the 1920s onwards and the general use of automobiles from the 1960s onwards led to the discontinuation of local railway lines. Often the passenger traffic was converted to bus operation first and later also the freight traffic was stopped.

Discontinued local railway lines (among others):

- Völkermarkt -Kühnsdorf– Eisenkappel ( Vellachtalbahn , Southern Carinthia)

- Treibach-Althofen-Klein-Glödnitz ( Gurktalbahn , Carinthia)

- Salzkammergut Local Railway (Upper Austria, Salzburg)

- Weiz - Ratten ( Feistritztalbahn , Styria)

New buildings

Remarks

- ^ Gordon A. Craig: History of Europe 1815-1980. From the Congress of Vienna to the present . CH Beck, Munich 1984, p. 180.

- ^ Alfred Werner Höck: Infrastructure policy and labor migration using the example of the Salzburg Tauern tunnel in the years 1901–1909 . In: Andrea Bonoldi, Hannes Obermair (eds.): Transport and infrastructure - Trasporti e infrastrutture (= history and region / Storia e regione 25/2 ). StudienVerlag, 2017, ISSN 1121-0303 , p. 41-63 .

- ↑ Railway Directorate in Mainz (Ed.): Official Gazette of the Railway Directorate in Mainz of January 21, 1922, No. 6. Announcement No. 71, pp. 73f.

- ↑ Displaced years (text accompanying an exhibition (2012) in Vienna) ( Memento of the original from November 16, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

See also

Austria

literature

- Karl Bachinger: The transport system. in: The Habsburg Monarchy 1848–1918. Volume I, Vienna 1973, p. 279 ff.

- The conductor. Official cours book of the Austrian railways. Publisher of R. v. Waldheim, Vienna 1901. Complete reproduction of the timetables for the area of today's Austria, in: Der Spurkranz. Special issue 1. Verlag Peter Pospischil, Vienna.

- Josef Dultinger : 150 Years of the Locomotive Railway in Austria - Contributions to Austrian Railway History. Verl. Dr. Rudolf Erhard, Rum 1987.

- Railway magazine . Bohmann-Verlag, Vienna.

- Hans Freihsl: Railway without hope. The Austrian railways from 1918 to 1938. An attempt at a historical analysis. Wilhelm Limpert Verlag, Vienna 1971.

- Lorenz Gallmetzer , Christoph Posch: 175 years of railways for Austria . Brandstätter, Vienna 2012.

- Richard Heinersdorff: The KuK privileged railways 1828-1918 of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Fritz Molden Verlag, Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-217-00571-6 .

- Alfred Werner Höck: Infrastructure policy and labor migration using the example of the Salzburg Tauern tunnel in the years 1901–1909 . In: Andrea Bonoldi, Hannes Obermair (eds.): Transport and infrastructure - Trasporti e infrastrutture (= history and region / Storia e regione 25/2 ). StudienVerlag, 2017, ISSN 1121-0303 , p. 41-63 .

- Paul Mechtler: The liquidation of the "Austrian Federal Railways" in 1938 . In: zeitgeschichte , October 1975 – September 1976 online

- Bernhard Neuner: Bibliography of the Austrian railway literature. 3 volumes, Vienna 2002.

- Elmar Oberegger: Rail transit in Upper Austria . In: Coal & Steam. In: Catalog of the Upper Austrian State Exhibition 2006. Linz 2006, p. 247 ff.

- Elmar Oberegger (Ed.): Publications of the information office for Austrian railway history. Sattledt 2007 f.

- Othmar Pruckner: Through Austria by train. Museum railways and luxury trains. Falter Verlag, Vienna 1992, ISBN 3-85439-092-0 .

- Victor von Röll (ed.): Encyclopedia of the railway system. Vienna – Berlin 1912.

- Rail traffic news magazine .

- Eduard Saßmann: Steam operation in Austria - The Vienna Federal Railway Directorate in color from 1963 . EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-88255-301-7 .

- Georg Schmid: Transport history. The material foundations of mobility. In: Contemporary History. No. 7, 1979/80, p. 218 ff.

- Josef Otto Slezak: The Locomotives of the Republic of Austria. Slezak publishing house, Vienna 1970.

- History of the railways of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Edited by Hermann Strach, Vienna, Budapest 1898 ff., Multi-volume standard work at the time.

- Georg Wagner: The ÖBB today. Railway between Burgenland and Lake Constance. Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-440-05303-2 .

The Austrian Railways in Fiction

- Hermann Bahr, aphorism from: Russian journey. Pierson, Dresden, Leipzig 1891. Quoted in: Wolfgang Minaty (Hrsg.): The railway, poems, prose, pictures. Insel Taschenbuch 676, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-458-32376-7 , p. 107.

- Thomas Bernhard: A child. Residenz-Verlag, Salzburg 1982. Quoted in: Wolfgang Minaty (Hrsg.): Die Eisenbahn, Gedichte, Prosa, Bilder. Insel Taschenbuch 676, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-458-32376-7 , p. 444 f. (How easy it is to blow up a large railway bridge).

- Franz Grillparzer, Epigram (1839) from: Complete Works. Volume 1, C. Hanser Verlag, Munich 1960–1965. Quoted in: Wolfgang Minaty (Hrsg.): Die Eisenbahn, Gedichte, Prosa, Bilder. Insel Taschenbuch 676, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-458-32376-7 , p. 54.

- Graham Greene : Orient Express. Novel. (Original: Stamboul Train) (c) 1958. Ullstein Taschenbuch 460. Ullstein-Verlag, Berlin 1964, p. 69 ff. (Journey from Ostend to Istanbul in the interwar period; third part: Vienna).

- Fritz von Herzmanovsky-Orlando: Emperor Joseph and the railroad attendant's daughter. (Play, 1957). In: Collected Works. Volume 3, Langen Müller Verlag, Munich 1957–1963. Quoted in: Wolfgang Minaty (Hrsg.): Die Eisenbahn, Gedichte, Prosa, Bilder. Insel Taschenbuch 676, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-458-32376-7 , p. 312 f.

- Fritz von Herzmanovsky-Orlando: Mask play of geniuses. Novel. Langen Müller Verlag, Munich, p. 17 ("... in the area of Leoben, this thunderstorm corner of European travel ...").

- Frederic Morton: Eternity Alley. Novel. (c) 1984. Franz Deuticke, Vienna 1996, p. 460 f. (Departure 1938).

- Robert Musil: Seriously wounded train. (1916). In: Collected Works. Volume 2, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1978. In: Wolfgang Minaty (Hrsg.): The railway, poems, prose, pictures. Insel Taschenbuch 676, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-458-32376-7 , p. 181 f.

- Johann Nestroy: Railway marriages . (Play, 1844). In: Collected Works. Schroll-Verlag, Vienna 1948–1949. Quoted in: Wolfgang Minaty (Hrsg.): Die Eisenbahn, Gedichte, Prosa, Bilder. Insel Taschenbuch 676, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-458-32376-7 , p. 65 f.

- Josef Roth: Station chief Fallmerayer (Joseph Roth: Works. Volume 5: Novels and stories. 1930–1936. P. 456–478: Station chief Fallmerayer. Novelle. 1933. With an afterword by the publisher. Gutenberg Book Guild , Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-7632-2988-4 )

- Helmut Qualtinger: The Sliwowitz Express. The blue-yellow danger or everyone their own S-Bahn. Reigen Express. In: Qualtinger's best satires (ed. Brigitte Erbacher), Langen Müller Verlag, Vienna 1973, ISBN 3-7844-1535-0 , pp. 24, 51.

- Carl Zuckmayer: As if it were a piece of me. Memories. (c) 1966. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1969, ISBN 3-596-21049-6 , p. 69 f. (Departure 1938).

The Austrian Railways in Popular Culture

- Gerhard Bronner, Helmut Qualtinger: The Federal Railway Blues

Web links

- Encyclopedia on the railway history of the Alps-Danube-Adriatic region

- On the railway history of old Austria

- Kontas Railway History of Austria (1893)

- Information office for Austrian railway history

- The railway networks of the Austrian federal states then and now

- Maps of the historical and current rail network

- Austrian Society for Railway History

- Contemporary document 1973: Business analysis of the ÖBB deficit

- Austrotakt 21 memorandum on the future of Austrian rail transport

- Early documents and newspaper articles on the history of the railways in Austria in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- G. v. Fuchsthal: The state railway connection Amstetten-Hrpelje-Triest St. Andrä. An ill. Guide (1887)