History of the cloth industry in Eupen

The history of the cloth industry in Eupen in the German-speaking Community spans several centuries and has seen numerous ups and downs from the first documentary mention in the 16th century until the last cloth factory was closed in 1989. It shows strong parallels and connections as well as dependencies with the textile history of the not far away cloth centers in Verviers in Belgium and in Vaals in the Netherlands as well as in Aachen , Monschau and Euskirchen on the German side. Since 2004, the Eupen cloth industry has been documented with the other cloth centers in the cross-border initiative Wollroute as well as in the culture and knowledge location cloth factory Aachen and since 1980 in the Eupen city museum . Especially in Eupen preserved and listed building standing mansions of drapers are a testimony to the heyday of the local cloth industry in the 17th and 18th centuries, in which up to four-fifths of the population was in part directly or indirectly employed.

history

The beginnings

Since there may have been cloth production in Eupen before the 16th century in an undetectably documented extent, there are only documented records from this period, such as the note about a wool merchant Aegidius Hauptmann from Eupen in 1554 or about visits by Eupen cloth merchants in 1572 at an exhibition in Frankfurt am Main . The influx of cloth craftsmen from Aachen is also documented, who at the beginning of the 17th century fled both from the Aachen religious unrest , if they were Protestant, and later from the effects of the rigid guild law there as a result of the Aachen gaff letter . In order to be able to work undisturbed in Eupen, at their request in 1679, the cloth makers were initially given the privilege of exempting the city from troops moving through and billeting and a year later, Charles II of Spain granted permission to produce fine cloth. A year later, on May 8, 1680, he granted them in a second decree that the cloth makers were allowed to take the wood they needed for the construction of the windmills and water mills and for the production of the necessary equipment from the Hertogenwald free of charge and that the cattle of the Manufacturers and workers in the surrounding forest districts could freely graze. This so-called “Hertogenwald privilege” is considered to be the hour of birth of the Eupen fine cloth industry, which also included manufacturers in Kettenis and Walhorn , among others . In a third decree of June 15, 1718, the Eupen cloth merchants were finally given by Emperor Charles VI. authorizes the duty-free import of wool, oil, dyes and all equipment necessary for the manufacture of cloths and fabrics.

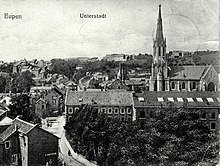

The first larger cloth manufacturers settled in the area of the Eupener Oberstadt along the Stadtbach and Gospertbach. However, as early as the early 18th century, there were occasional efforts to settle on the banks of the more fertile Weser and Hill streams in the lower town of Eupen, where mostly existing mills were taken over and set up as fulling mills . There it was, for example, the Salm brothers, who started up three fulling mills in the area of the Weserbogen around 1750 and set up a dye works in the Oe, as well as the Kleblanck family, who ran the Kreuzenhammer fulling mill in the Haas, and the Blanckaert family, who were in the middle of the 17th century Century in which Haas founded the first known dye works in Eupens.

During the period of Austrian rule over Eupen from 1714 to 1794, the cloth industry experienced its first extensive economic boom. This is often reflected in the baroque patrician houses still preserved today in the upper town, such as the houses Grand Ry , Mennicken , Gospertstraße 52 and 56 or Rehrmann-Fey . contrary. Above all, the Austrian government promoted the development through protective tariffs and the permission of the duty-free import of raw materials as well as the religious freedom of the cloth entrepreneurs. The Eupener cloths were sold in Central and Western Europe, in Poland and Russia as well as in the Levant and India and quite soon hundreds of workers had to be recruited, mainly shearers from France, the Austrian Netherlands or the Kingdom of Prussia .

- Patrician houses with cloth manufacturers (selection)

The form of organization common at that time was the publishing system , in which many of the preparations required for cloth manufacture, such as spinning, washing, combing, milling or weaving, were carried out by wage workers or entire families working from home. The head of a company was usually the cloth merchant himself, who was assisted by a cloth maker, called “Baas” in Eupen, who in turn controlled the cloth workers and outsourced work to home workers or contract weavers. Only fine merino wool from Spain was used.

The finishing and the shearing, i.e. the finishing, which was decisive for the smoothness and shine of the valuable fine cloth, finally took place under the supervision of the cloth makers and dealers in the so-called "Schererwinkel", i.e. in workshop buildings, which are mostly eight-sided or additions to the patrician houses of the cloth entrepreneurs. Although there were no guilds in Eupen, the shearers in particular repeatedly formed interest groups, fought for fair pay or humane working hours and did not shy away from protest actions such as the first general strike in Eupen in 1721 or when they participated in the "Läutebieraufstand", which mostly remained unsuccessful or were violently suppressed.

Overall, at the end of the 18th century, the Eupen cloth handicraft counted around 60 larger and smaller cloth manufacturers and around 1500 cloth shearers. Above all, the entrepreneurial families Fremery, Grand Ry , Gülcher, Hüffer, Klebanck, Mayer, Peters, Rehrmann, The Losen and others laid the basis for what was known as the “golden years” of the Eupen cloth industry. The fine cloth from Eupen factories at that time had a high priority in Europe and the cloth manufacturers enjoyed high reputation. This was recognized by Franz Stephan von Lothringen , the husband of the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa , who had increasingly enticed entrepreneurs from the Austrian Netherlands to Austria, which he had achieved in Eupen in the person of Johann von Thys .

From early industrialization to the First World War

After the country came under the rule of France from 1794, this had a significant influence on the cloth production in Eupen. Due to the abolition of customs duties to France and the elimination of English competition through the continental blockade from 1806 as well as major orders for the French army, the Eupen cloth industry reached the absolute climax of its entire textile history. In addition, the first technical advancement of the looms began to increase the weaving speed, and the first wool spinning machines were introduced from 1798 by William Cockerill, Senior . For the new technology, however, up to 14 spinners were required to supply a loom with sufficient thread supply at the required speed. In a further development step, semi-mechanical and fully mechanical looms as well as mechanical spinning and shearing machines were introduced, which were less labor-intensive and with which a first industrialization boost began.

In 1802, the Monschau manufacturer and later district administrator of Eupen, Bernhard von Scheibler, decided to settle in Eupen next to the Weser bridge, where he immediately had a stately house and company building built. In 1807 Scheibler introduced mechanical gouging machines and established the first mechanical wool spinning mill in the wider area of Aachen. This was the hour of birth of the industrial Eupen cloth factories, in which gradually all work processes, from preparation to final production, were accommodated and which therefore developed into full cloth factories over time. The boom can also be seen in the figures, according to which in 1812 around 8,500 of the almost 11,000 inhabitants of Eupen were employed, and around 1,500 of them were home workers for a total of 46 cloth processing companies.

In order to enable the machines to be driven by means of water wheels, new businesses have now been established, especially along the more abundant flowing streams Weser and Hill in the lower town, which led to a strong dynamic in textile production there at the beginning of the 19th century, resulting in a new, up-and-coming industrial and residential district was created. The focus of production during these years was on fine, light-colored and only lightly milled cloths made of coarser wool, so-called seraglio, as well as on dark cloths, known as "Eupener Black" and used for suits and uniforms.

The withdrawal of the French and the takeover of Eupen by Prussia in 1815 led to drastic changes for the local cloth manufacture and a wavy but continuous downturn in the cloth industry began. This began with the collapse of the French sales market, which could not be absorbed despite new markets in Spain, Italy or China, and the abolition of the continental barrier. After 1816, the textile mills were also equipped with steam engines and wanted to use the first cylinder-cloth shear machine at Werth place in 1821, the company "Gebrüder Stolle & Co.", which should replace 13 to 14 Scherer, it came as a result to a revolt of the cloth Scherer , in the course of which the not yet assembled clipper from Stollé's farm was thrown into the Gospertbach in parts. This uprising was put down by District Administrator Scheibler with the help of the police and the citizens' militia as well as gendarmes from Aachen, and the ringleaders were sentenced to five years in prison. Overall, the unrest intensified the economic crisis, which resulted in increasing poverty in the population and which was to be absorbed by the introduction of various schools for the poor, poor funds and women's associations.

In addition, the Europe-wide trade crisis that broke out in England in 1825 and the associated speculative and currency crisis had an impact on wool and cloth prices, which then fell sharply and thus impaired the profits of cloth entrepreneurs. In addition, the founding of Belgium in 1830 created great competitive pressure in textile production in Eupen through the factories in Verviers, now Belgium, which worked at dumping wages. The consequence was a sharp increase in unemployment among the Eupen cloth workers, there was further unrest on the streets and a reduction in wages. In order to earn a living, not only women but also children and young people under the age of 16 had to work, some of whom spent up to ten hours in the factories. Some families left the Eupen area under this pressure and moved to other European cloth centers or emigrated to America.

The cloth industry only recovered temporarily at the beginning of the 1830s, after trade with Russia was initially able to revive, but a few years later it was again restricted by new customs regulations. Eupen's important Levant trade was also subject to constant fluctuations, depending on whether armed conflicts were taking place there between the Ottoman Empire and its neighbors. Likewise, since the 1870s, the importance of most foreign sales markets has slowly declined, as independent cloth productions had emerged there and imports were made more difficult by protective tariff policies.

Furthermore, a consistently sluggish degree of mechanization in the factories resulted in a drop in turnover, so that the publishing system had to be maintained for many decades and in 1877 around a third of all workers were still working from home or in contract spinning mills. In order to accelerate the modernization, several machine factories were founded in Eupen between 1860 and 1870, which, among other things, manufactured machines for fabric manufacture. Nevertheless, full cloth factories in Eupen, such as those set up in Aachen in the extensive factories there, remained rather the exception.

In addition, the cloth contractors suffered from inadequate transport connections, as Eupen only received a rail connection to Herbesthal in 1864 , whereas the cloth centers in Aachen or Verviers, for example, had already been connected to the railway network around twenty years earlier. In Eupen, too, the unsafe water situation in the streams, especially in the upper town, had a negative effect, where operations could not always be maintained due to drying out in summer or icing in winter, unlike in Aachen, where the entrepreneurs were based Thermal springs or in Verviers, where the cloth mills benefited from the construction of the Gileppe Dam , completed in 1878 .

From the last quarter of the 19th century, however, again larger orders ensured a prosperous sales market in the USA, where there was hardly any well-known cloth industry, to compensate for the aforementioned disadvantages. In addition, at the end of the 19th century, the change from the predominant carded yarn to worsted yarn production brought about a last revival of the economy. These yarns previously had to be imported mainly from Verviers, here for example from the local cloth factory Peltzer & Fils , which had already switched to worsted yarn around twenty years earlier and had branches in Eupen since the late 1860s. There, the Verviers-based company had taken over the “Peters Spinning Mill” and continued to run it as “Peltzer & Fils” and set up a sheepskin dyeing factory under the name “Peltzer & Cie.”. It was not until 1890 that worsted yarns were produced in Eupen by the worsted yarn spinning mill “Gülcher & Grand Ry”. A few years later, in 1906, Kammgarnwerke AG was founded , which was formed on the initiative of Robert Wetzlar from the merger of several individual companies.

All this led to the fact that from the middle of the 19th century various companies had to merge or even close, and the number of employees in the cloth factories in the Eupen district rose from 3,624 people in 19 companies (1861) to 2,600 people in ten companies (1894) 2000 people in only five factories fell in 1913, 681 of them in worsted mills. The development in the Eupen cloth industry was thus diametrically opposed to the competition in Aachen, where several large companies were founded in the 19th century, some with over 1000 employees.

In order to be able to represent the interests of the cloth workers in these difficult times, especially on the occasion of the planned introduction of the two-chair system, whereby one weaver was supposed to operate two looms at a time, which inevitably led to layoffs or wage cuts, the Christian-Social Textile Workers' Union was established in 1896 for Eupen and the surrounding area was founded, which in turn was the nucleus of the later “Central Association of Christian Textile Work in Germany”.

The downward spiral of the cloth industry in Eupen also had an impact on the development of the city itself, as the larger, factory-like companies had almost completely settled in the lower city and provided an up-and-coming district there. In return, the long-established businesses in the Upper Town were the first to be affected by the closings, and the old drapery houses were gradually transferred to other owners or uses from the middle of the 19th century.

Rising and falling in the 20th century

The burgeoning boom in the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, among other things due to the previously mentioned US business, the production switch to worsted and the production of military cloths, did not last long because the First World War and its political consequences again led to massive sales problems. As a result of the Versailles Treaty , through which, among other things, the Eupen district had been awarded to Belgium from 1919, trade relations with Germany, to which almost 95% of goods had recently been exported, were cut off and the goods were cut off when new German import duties came into force from 1925 subject to duty. As a result, for example, the Eupen company “Wilhelm Peters & Sohn” set up a branch for worsted yarn production in Aachen as early as 1919. The Belgian domestic markets, which are now duty-free, and the neighbors in France and Luxembourg were only able to compensate for the decline in sales to a limited extent, as the Verviers factories dominated these cloth shops. Further mergers and closings finally led to the fact that around 1924 only five cloth mills, two spinning mills, the worsted yarn mill, a contract weaving mill and a dye works were still producing in Eupen.

The problem was exacerbated by the global economic crisis in 1929 and the forcible incorporation of Belgium into the German Reich from 1940 to 1944 during the Second World War , as a result of which the Belgian market collapsed. In order to be able to survive economically in these war years, the few still existing Eupen companies were forced to work as wage workers for some Aachen cloth factories.

After the war and Eupen's reintegration into Belgium, new sales markets had to be found again, although former customer countries in Europe, Asia and overseas have now developed into competitors. In addition, new products such as fabrics made of synthetic fibers, jeans from America or cheap goods from low-wage countries, especially from Asia, flooded the Belgian market and the number of employees fell in 1955 to only 1,400 employees, of whom 400 in the three remaining cloth mills, About 700 were active in the two worsted spinning mills and about 300 in the other companies. This ultimately led to the gradual closure of the remaining Eupen cloth companies, the last of which, the worsted yarn factory, ceased operations in 1981 and was finally dissolved in 1989.

Important former cloth factories (selection)

Ackens, Grand Ry & Cie.

The company, which is one of the oldest drapery shops, was set up around 1750 by André Grand Ry (1705–1751) on Marktplatz 8 in the upper town and came into the possession of the Heinrich Ackens family (1738–1794) for a short time. When his daughter Barbara Cornelia married Jacques Charles Maurice von Grand'Ry (1777–1840) in 1807, the clothmaker's house on the market square came back into the possession of the Grand Ry family.

The cloth manufacture there was continued by Heinrich Ackens from 1777 as "Ackens, Grand Ry & Cie". Later the company set up two more factory buildings, first from 1853 in house Haasstrasse 3, formerly Roemer and from 1869 in house Haagenstrasse 2 (corridor Schafskopf), formerly Pontzen, where they used hydropower for their spinning, fulling, hoeing and shearing machines made use of the Weser. The headquarters and storage room remained on the market square until the company was dissolved.

Ackens, Grand Ry & Cie. temporarily employed up to 385 people and remained in family ownership until it was dissolved in 1899, most recently under the direction of Alfred Clémens Hubert von Grand'Ry (1872–1943).

Hüffer & Morkramer

Johann Gerhard Hüffer (1751–1823) had owned a cloth factory in the right wing of Kaperberg 4 in the Eupener Oberstadt since 1783 , in which his colleague Franz Arnold Morkramer (1766–1817) owned shares. After Morkramer's death, Johann Gerhard's nephew Anton Wilhelm Hüffer took over his shares and in the same year set up a new factory in the Oe am Weserbogen in the lower town. After the death of his uncle in 1823, Anton Hüffer inherited his factory on the Kaperberg and significantly expanded both facilities into a cloth and buckskin factory. At the same time, he set up a school for the children of his poorer employees in his company, which employed around 291 workers, and set up a company health insurance fund.

After Anton Hüffer devoted himself increasingly to the coal and steel industry from the 1840s , he transferred the inherited company on the Kaperberg to his son Eduard (1812–1891), who ran the business as “E. Hüffer & Cie. ”And decommissioned around 1890 and at the same time bequeathed the building wing to the city of Eupen. In 1842 Anton Hüffer handed the factory in the Oe over to his son-in-law Julius The Losen , which from 1873 traded as "Hüffer & The Losen". Most recently it was headed by Max Fromann and Johann Justus Krantz (1842-1919) and dissolved at the beginning of the 20th century.

JF Mayer cloth factory

Johann Friedrich Mayer (1762–1830) came from Heilbronn and after moving to Eupen initially founded a small cloth company. In 1797 he merged this with the cloth company Jacob Breuls & Söhne , which had been based in Klötzerbahn 27 in Upper Town since the end of the 1770s, initially together with Leopold The Losen. Mayer also chose this location as the headquarters and henceforth traded as Jacob Breuls, Söhne & Mayer .

The merger was dissolved on June 1, 1825 and from then on Mayer continued to run the business on the Klötzerbahn, which worked in the publishing system, as sole responsible under the name of Tuchfabrik JF Mayer . In 1845 he handed it over to his son Julius Mayer (1806-1859), who moved the company to the Oestrasse area, but kept his residence on the Klötzerbahn. Equipped with the latest machines, the medium-sized company produced with only a maximum of 172 employees, preferably for the markets in the East Indies, China, Japan and the Levant and won on international economic exhibitions numerous awards. The focus of production was on the manufacture of hat stumps and from 1877 under Julius Friedrich Mayer (1839–1890) on felt fabrics.

The consequences of a major fire in 1889 were quickly remedied and resumed a year later under Alexander Mayer (1867–1943) focusing on fine worsted fabrics and buckskins. Although the company was still one of the leading cloth factories in Belgium in the difficult economic times after the First World War and also after the Second World War, it could not hold up in the long term and had to be liquidated in 1961 by its last director Curt A. Mayer (1903-1991) become.

Sternickel & Gülcher

The cloth factory was founded in 1801 by Johann Jacob Gülcher (1779–1862) in Gospertstrasse in the upper town. About four years later, Benjamin Sternickel joined the company and, after he left the company in 1813, Christian Bernhard Sternickel, who then traded as "Sternickel & Gülcher". In 1829 the company was relocated to the district of Hütte on the banks of the Hill in the Lower Town of Eupen, where it was transferred to a plant with new buildings for an additional spinning mill, fulling mill and finishing.

During these years, the company developed into the largest cloth factory in Eupens with 750 employees. In 1852 the management of the company was transferred to the sons of the founders, Alfred Sternickel and Arthur Gülcher (1826–1899), who took over sole management after Sternickel's departure from 1861. In the meantime, extensive building extensions were made in the years 1850, 1855 and 1869 and the operation was technically modernized.

After Gülcher, Johann Jacob (Ivan) Homberg (1850–1924) headed the company, which was acquired by Theodor Küchenberg (1876–1966) around 1920 and converted into a full cloth factory under the name “Eupener Textilwerke” (“Usines Textiles d'Eupen SA ”) has been converted under Belgian law. From then on, until she went bankrupt in 1968, she specialized in the production of fine cloths for men’s clothing, coat materials, women’s fabrics and officer’s cloth.

Leonhard Peters

The cloth factory with fulling mill was set up in 1803 by Leonhard Peters (1761–1813) in the Eupener Haasstraße directly in front of the St. Josef church and in its prime around 1836 had up to 440 and around 1895 only around 250 employees. In 1896, under the direction of Alfred Peters (1851-1934), the two-chair system was to be introduced, as a result of which there was a workers' uprising in the company. Peters only gave in to a limited extent and decided not to introduce the two-chair system, but pushed through drastic wage cuts. In 1936 the company was shut down.

Wilhelm Peters & Son

The cloth factory was founded in 1837 by Wilhelm Peters (1814–1889), a nephew of David Hansemann , in Werthplatz 5–7–9 in the Upper Town as a contract weaving mill, and a year later he was able to work on his own account. In 1841 he first leased the fully equipped Grand Ry cloth factory in Langesthal on the banks of the Weser and began producing colorfully patterned cloths from dyed wool, which became a hit. Three years later he took over the entire local factory and in 1867 the neighboring Nicolai weaving and fulling mill. Through further expansion measures and technical modernization, the company developed into a full cloth factory with over 500 employees by 1879. In 1887 a shed roof hall was built for the weaving mill, where the workers worked on up to 230 looms in the following years.

After the First World War, the company converted its Eupen plant into a stock corporation in 1922 and in 1924 set up a branch for worsted yarn production in Aachen. Under the new name of "Wilhelm Peters & Co. SA", the company specialized in the production of the finest worsted fabrics for men's fashion and carded yarn fabrics for jacket fabrics and loden. After the Aachen plant had to be shut down in 1961, the main plant in Eupen was finally closed by Wilhelm Peters' great-grandchildren in 1972 due to a lack of orders. Some of the buildings in question are the only remaining industrial buildings of the Eupen cloth industry, along with the Kammgarnwerke buildings.

Kammgarnwerke AG

The company Kammgarnwerke AG was founded in 1906 on the initiative of Robert Wetzlar on the Weser. The cloth factories "Wilhelm Peters & Sohn" and "Gülcher & Grand Ry" from Eupen and the textile companies Delius , Königsberger, GH & J. Croon and Dechamps & Drouven from Aachen were involved .

From 1932, the Kammgarnwerke took over a branch of the dissolved Nordwolle Group in Langensalza in Thuringia and continued it as a subsidiary under German management as Kammgarnwerke Langensalza GmbH, which became a state-owned company in 1968 . After the dissolution of the GDR, the former Belgian owners were compensated with several million DM in 1992.

After falling sales, the worsted yarn factory was shut down in 1981 as the last textile company in Eupens and its stock corporation was dissolved in 1989. The properties were gradually taken over by the expanding Eupen cable works .

See also

literature

- The fine cloth manufacturer in Eupen, all its secrets, advantages and prices together with tables , Gotha Verlag in the Ettinger bookstore 1796 ( digitized Bayerische Staatsbibliothek 2012 )

- The industry in Eupen , in: Christoph Rutsch: Eupen und Umgebung , C. Jul. Mayer, Eupen 1879, p. 126–142 ( digitalized )

- Leo Hermanns: The beginnings of the fine cloth manufacture in Eupen , in: Geschichtliches Eupen , Volume 15, Markus-Verlag 1981, pp. 150–171, pp. 163–169

- Leo Hermanns: Die Tuchscherer, Eupen's first solidarity workers , in: Geschichtliches Eupen , Volume 16, Markus-Verlag 1982, pp. 150–171

- Leo Hermanns: Trade and Commerce in Eupen. The Eupener fine cloth production , in: Geschichtliches Eupen , Volume 25, Grenz-Echo Verlag 1991, pp. 69-84

- Norbert Gilson: History of the textile industry in the Verviers, Eupen, Aachen area with special consideration of the woolen cloth industry . Rheinisches Industriemuseum, Euskirchen 1997, pp. 20, 21 and others ( pdf )

- Els Herrebout: The history of the Eupen cloth industry in comparison to other woolen cities in Europe , in: Geschichtliches Eupen , Volume 38, Grenz-Echo Verlag 2004, pp. 45–83

- Marga van den Heuvel: The fine cloth, ups and downs of the cloth industry using the example of the Wilhelm Peters family of textile entrepreneurs from Eupen and Aachen from 1830 to 1970 , Grenz-Echo Verlag, Eupen 2014, ISBN 978-3-86712-089-0

- Ministry of the German-speaking Community (ed.): The industrial history of the Eupen Lower Town , Eupen July 2015 ( pdf )

Web links

- East Belgium - economic area with a past , report on the website of the IHK Eupen

- Eupen wool route

- Walter Buschmann: Eupen , on rheinische-industriekultur.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eupen - Wool Route , on Grenzgeschichte.eu

- ↑ The history of the place , in: Christoph Rutsch: Eupen und Umgebung , C. Jul. Mayer, Eupen 1879, pp. 21-22 ( digitalized )

- ↑ The history of the place , in: Christoph Rutsch: Eupen und Umgebung , C. Jul. Mayer, Eupen 1879, p. 26 ( digitalized )

- ↑ Detlef Stender: Cloth makers' buildings in the Eupener Oberstadt , on the Euregio-Maas-Rhine industrial museums page

- ↑ Guild efforts of the Eupener cloth shears in the 18th century , on Grenzgeschichte.eu

- ^ Leo Hermanns: Johann Thys van Eupen, an economic pioneer of the 18th century in Carinthia , in: Geschichtliches Eupen, Volume 14, pp. 81–96, Markus-Verlag, Eupen 1980

- ↑ textile workers' uprising in the shadow of Werth Chapel , in: Grenz-Echo from November 28, 2011

- ↑ Excerpt from the chronicle of the city of Eupen from 1825 , on Grenzgeschichte.eu

- ^ Eupen - an industrial center in West Prussia , on Grenzgeschichte.eu

- ↑ 90 years of the Christian trade union movement in Eupen , on Grenzgeschichte.eu

- ↑ Cloth factory Peters Aachen , on the pages of the wool route

- ↑ trademark Ackens, Grand Ry & Cie. , on ostbelgien.net

- ↑ Portrait of Haus Haasstrasse 1–3 in Eupen , on ostbelgien.net

- ↑ Portrait House Haaagenstraße 2 in Eupen , on ostbelgien.net

- ↑ Heinz Warny: Lebensbilder aus Ostbelgien , Volume 1, Grenz-Echo Verlag, Eupen 2017, pp. 10-13

- ↑ Hüffer & Morkramer , company portrait on albert-gieseler.de

- ↑ Heinz Warny: Lebensbilder aus Ostbelgien, Volume 1, Grenz-Echo Verlag, Eupen 2017, pp. 84–85

- ↑ Festschrift JF Mayer 1797–1947 on the occasion of the company's 150th anniversary in 1947.

- ↑ Joh. Friedr. Mayer , company portrait on albert-gieseler.de

- ↑ Data from the Gülcher cloth factory at albert-gieseler.de

- ↑ Usines Textiles d'Eupen SA share

- ↑ Heinz Warny: live pictures from Ostbelgien , Volume 1, boundary echo Verlag, Eupen 2017, pp 130-131

- ↑ Wm Peters & Cie , company portrait on albert-gieseler.de

- ^ Share Kammgarnwerke on aktiensammler.de