History of cinema

The history of cinema began in the second half of the 19th century with stalls at fairs. In the first half of the 20th century, the cinema became an established art and cultural institution. At the end of the century it fell into a deep crisis , mainly due to competition from television . Since then, the cinema has been revived through various concepts.

precursor

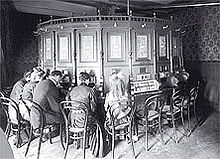

The precursors - and at the same time the starting point - of the cinema were show booths and panoptics, as they were mostly to be found at fairs and in cities. In addition to all kinds of curiosities, optical illusions have always been presented there. Stereoscopes , for example , which were used to present three-dimensional photos to the visitor , were particularly popular and often found . The German entrepreneur August Fuhrmann was successful here with the Kaiserpanorama system introduced in 1880 .

In 1893 the inventor Thomas Alva Edison presented the kinetoscope developed by his chief engineer William Kennedy Laurie Dickson - a showcase in which one person could watch short films. The invention spread to the United States before the Lumière Society's cinematograph reached the United States. The Lumière brothers were able to use their technology to record and play films. In the United States - also before the Lumière brothers - Thomas Armat invented a film projector that freed the viewer from the peep box and thus made it possible to share film experiences.

Silent movie era

First film screenings

The first cinema-style film screenings, i.e. film projections for a paying audience, took place in 1895:

- from May 20th for a short time in New York in a specially furnished room by the Latham family (father Woodville Latham and sons Otway and Gray),

- from November 1st for a month in the Berlin “ Wintergarten ” by the Skladanowsky brothers as the final act of a variety program and

- from December 28th - with the greatest influence on cinema history - for a whole year in a specially furnished room (“Salon India” of the “Grand Café”) in Paris by the Lumière brothers .

The first documented public cinema screening in Austria took place on March 20, 1896 in the Vienna Teaching and Research Institute for Photography and Reproduction Processes with the Lumière cinematograph in front of an invited audience.

“ Moving images ”, often under the term “living photography”, were a new attraction in show booths and pan-optics, the new medium was often called that at that time. Since the Lumière brothers from 1896 toured the big cities of the world with their "Réversible", the cinématograph - which enabled both playback and recording - and advertised their device, many show booth owners and other business-minded people procured the device. To compete with the Lumière brothers' cinématographe, Edison bought the projector version from Armat in 1896 and produced it under the name Vitascope . The inventors and businessmen Max and Emil Skladanowsky and William KL Dickson also developed film apparatus, but their film recorders and projectors did not spread as quickly as the cinematograph. So early filmmakers and amateur filmmakers used it to record documentary scenes. Show stalls, panoptics and the first cinema owners used it as a projection device.

In the beginning, everyday scenes or played jokes were recorded and shown. The films were black and white , silent, with an image size of 18 × 24 mm, i.e. an aspect ratio of 3 to 4 on Kinetoskop film. The Lumière brothers used an aspect ratio of 4 to 5. Initially, 15 to 20 images per second were taken and presented. Up to the sound film this rose to 30 and more frames per second in the cinema. Apart from the show booths, inns and hotels were the places where the film was shown. In some cases, suitable rooms have been permanently redesigned for this purpose. In other cases, especially in smaller towns and rural areas, they were only occasionally used for film screenings, such as when traveling cinemas were visiting. These moved from town to town - sometimes it was circuses that acted as projectionists - to show their film program in inns or community halls for several days. Due to their constant wandering, they only needed a few films, especially in the first few years, that they could repeatedly show to new audiences. In the USA and Germany, the variety theater program has also been enriched with films.

The films rarely exceeded a minute in length . In the first few years, the attraction of seeing “living images” alone was sufficient to attract large crowds as an audience. Only when the sensational value was gradually exhausted were current events documented or short, usually funny stories recorded. The documentary and the feature film or film comedy were made. The public interest could still be kept alive. In many show booths, film screenings took up more and more space, while other curiosities were pushed back. Little by little - around 1900 - many gave up the show booth business completely and devoted themselves only to film screenings. The first cinemas in fixed rooms emerged. However, it was not until the First World War that all cities in Europe and the United States were supplied with cinemas . After that, the expansion of the existing cinemas was pushed ahead with ever more elaborately produced and longer films.

The creation of the movie theater

From the turn of the century, more and more people saw the medium of film as a permanent achievement rather than a curiosity. Cinemas were gradually opened - that is, facilities that primarily served the regular screening of films. In the beginning, film screenings were occasionally given in restaurants and their halls in the cities. For this there was the rental of cinematographs. The demonstration machines then increasingly remained in place and the presentations took place regularly. Shops that were previously empty or abandoned bars became “shop cinemas”. The increasing number of cinemas led to considerations to limit their number in order to ensure quality. If there were opportunities and if there was a corresponding need, dance halls or halls from inns were converted into hall cinemas. Innkeepers and merchants became cinema owners. The growth of film production served more and more genres and the first film stars emerged. The size of the cinemas grew. Until the 1920s, independent “cinema palaces” emerged in the major cities of Europe and those of the United States. In their architecture and elegance, these tied in with the pomp and furnishings of theaters and opera houses of that time, and film was increasingly recognized as an art form in its own right. Traveling cinemas continued to play an important role in rural areas and smaller towns in the first decades of the film. At the end of the 1920s, the owners of such cinematographs became sedentary and used their equipment in suitable rooms that became cinemas.

The Kintöppe and the corresponding American Nickelodeons increasingly became cinemas from 1910 onwards, opening their halls in ever larger and more luxurious new buildings. Initially, temporarily converted shops were the rule. From the bar with the spectacle of "moving images", the halls of the beer gardens on the brewery premises became large cinemas. As electrification progressed, more and more "movie theaters" were opened as permanent facilities.

The first German cinema opened on April 25, 1896 in Berlin in the house at Unter den Linden 21. Became known knob Lichtspielhaus Spielbudenplatz the Hamburg Reeperbahn . In 1900, Eberhard Knopf bought a demonstration machine for his “concert and machine shop”. The first program consisted of three parts, “1. Arrival of a railway train, 2. Embarkation on the high seas and 3. A farmers' competition ”. In 1906, due to its great success, the theater moved to the newly built extension. The Swedish Saga , which opened in 1906 , the Pionier cinema in Stettin (since 1945 Szczecin) and the Gabriel Filmtheater in Munich, all of which opened in 1907, are among the oldest cinemas in the world that are still in use today . The Danish Korsør Biograf Teater , which also opened in 1907, is the oldest purpose-built cinema building in the world that is still in operation . The oldest functional cinema buildings in Germany that are still in operation are only slightly younger, those of the Burg Theater in Burg (near Magdeburg) and the Weltspiegel film theater in Cottbus , both of which were completed in 1911. Austria's first cinemas, such as the Münstedt Kino Palast or the Klein Kino , were located in the Wurstelprater in Vienna , where they offered cinema screenings for the first time in 1904 and 1905.

The heyday of the film palaces

| Continent selected states / region |

number |

|---|---|

| Europe | 21,642 |

| Germany | 4300 |

| Austria | 500 |

| Switzerland | 130 |

| England | 3700 |

| France | 3300 |

| Italy | 1500 |

| Spain | 1500 |

| Hungary | 370 |

| North America | 21,519 |

| United States | 20500 |

| Canada | 1019 |

| Asia | 3,690 |

| Japan | 850 |

| Asia Minor | 71 |

| Central / South America | 3,598 |

| Australia | 1,200 |

| Africa | 644 |

| worldwide | 51.103 |

From 1913, when an elegant large-scale cinema modeled on the theater was built in New York in order to give the more demanding film ( Film d'Art ) a more appropriate setting and thus protect it from hostility from “cultural guardians”, the first emerged in Western countries Movie palaces. In the 1920s in particular, more and more cinemas developed into such elegant large-scale cinemas. The name "Filmpalast" reminds the palaces of antiquity and baroque. The large cinemas offered the visitor entertainment and food that went far beyond just watching a film. They resembled covered annual fairs and often held many hundreds of visitors. The Mercedes-Palast in Berlin accommodated 2,500 guests, the Ufa-Palast on Gänsemarkt in Hamburg accommodated 2,665, the Busch-Kino in Vienna 1,800. In the United States, the largest cinemas were in New York . In the 1920s, there were mostly cinemas with over 3000 seats. The largest cinema was the 6200-seat Roxy Theater .

In 1927 around six billion people worldwide watched films in cinemas, half of them in the USA alone. The British film theorist L'Estrange Fawcett tried to explain this mass phenomenon in 1927 using the example of New York's cinema palaces. There they tried not only to show visitors a splendid, elegant, different world through interior and exterior architecture, they were courted by a large number of employees like a valuable guest. He wrote:

“Even the vestibule [...] is worth seeing. The wasted space of a cathedral is combined there with the radiant splendor of overloaded ornamentation , which pleases the masses and attracts them. [...] Let's go into a New York film palace after business hours on a hot summer afternoon. The overheated atmosphere, the dust and the hustle and bustle of the capital's streets are unbearable; The people drag themselves like dull flies through the glowing cauldron - then a splendidly uniformed porter throws open the double wing doors of the cinema, and when we enter we feel transported into a more beautiful world. The temperature immediately dropped by 6 to 7 degrees, pure, fragrant, ice-cold air floods the whole building [...] everything straightens up, you feel revitalized and life is once again worth enjoying. "

Fawcett attaches particular importance to the mezzanine , which should not be missing in any cinema palace. Marble columns, crystal chandeliers and upholstered divans invited people to relax. “In the vestibule, fresh fountains splash against marble nymphs and mosaic walls. […] Often the cinema theaters even contain small museums where valuable relics are kept in showcases - the armor of Alexander VI. Borgia, the figurehead of the ' Mayflower ', [...] and similar childish treasures. "

The staff at the entrance to the actual screening room were dressed according to the motifs of the respective film; the guest was personally escorted to his seat. An organist played "muted chords" on a large organ. The performance itself then typically went like this:

- Admission: 75 cents (at that time the equivalent of 3 marks , which would correspond to purchasing power of 19.5 euros in 2005)

- The performance begins with a “ little singspiel, dance pantomime or the like ” lasting about 15 minutes , accompanied by a cinema orchestra

- Then the daily events are played ( newsreel )

- short comedy film

- Main film: usually around 80 minutes

- The same program was repeated all day from 1 p.m. to midnight.

Film critic Fawcett concludes: "As you can see, vast sums of money are spent in America trying to attract audiences without losing out on practical business methods."

Film screenings during the silent era

A film screening in the silent film era differs significantly from a film screening today. The most striking difference resulted from the silence of the films themselves. The second striking difference is that in the early days of cinema history, when the films were initially between a few to 20 minutes and finally an hour or longer, a cinema show included several films. The viewer was offered a film program, with the "main film" as the centerpiece.

In order to compensate for this shortcoming - which was one thing from the 1910s at the latest, when the films became longer and the plots gradually more complex - several practices developed.

In the beginning, when most cinemas were still converted rooms in hotels, restaurants or show booths (in the USA from the beginning Nickelodeons ), there were film explanations. In Japan, this profession even survived the end of the silent film era and was known as Benshi for a long time into the sound film era. In Europe and the USA, however, the film explainer was soon replaced by subtitles that roughly reproduced the storyline or dialogues. In addition, instruments - mostly pianos or cinema organs - were used early on to accompany the silent film. While these pieces were initially improvised or adapted from the contemporary popular repertoire - or stubbornly existing piano pieces were played independently for the plot - this practice soon gave rise to the profession of film composer , who wrote his own compositions for silent films , which the pianists or other musicians in the cinemas were played. In large cinemas - which were often premiere cinemas that played the latest films and also had more expensive admission prices - as they emerged from the 1910s, but especially in the 1920s, often entire orchestras and sometimes choirs and were operated Opera singers used.

Small cinemas that could not or did not want to afford original compositions continued to hire musicians who played from cue sheets or themed lists specially created for such purposes. These included the right background for various film scenes - from happy to serious and dramatic to tragic. Fair organs and pianolas could also be found in small, cheap cinemas. Noise makers or their own machines provided additional acoustic background music.

In the first few years, when everyday scenes and news reports were mainly produced for a few minutes, these short films were shown as part of the program of variety theaters, circuses or in rooms in show booths or restaurants that had been converted into showrooms. With the increasing length and entertainment value of the films, other program items were neglected and when it became foreseeable that the film would not remain a temporary curiosity, the first cinemas often emerged from such rooms, which offered film screenings as the only "attraction".

Before 1910, feature films were usually one role ( one-reelers or one-act plays ), from around 1910 an average feature film reached a length of 20 minutes - i.e. two film roles - and after the First World War, around 1920, the feature film established itself with play lengths of 60 and more minutes. Depending on the length of the main films shown in the cinemas, the compilation of film programs that cinema-goers got to see for their entrance fee developed. An integral part of such a program were reports of current events from the city, the country or elsewhere in the world - such as major social events, major fires, natural disasters. This program item developed into a weekly newsreel , which came to the cinemas every week with new reports, and which lasted much longer worldwide than the silent film era.

Other items on the program were mostly comic shorts or cartoons, each lasting around five to 20 minutes, and from the 1910s also episodes of film series - such as detective series - as well as various other shorter films such as documentaries or cultural films. The main film was usually shown last, as the highlight of the performance.

Until 1927 there were almost exclusively silent films . The films, which initially only lasted a few minutes, became longer and longer towards the end of this era . The monumental works of the silent film era, some of which lasted several hours, include Cabiria (1912), Birth of a Nation by David Wark Griffith , Metropolis by Fritz Lang , Ben Hur by Fred Niblo (with color sequences) and Napoléon by Abel Gance (the already experimented with color film , 3D and wide screen film ).

Change from silent film to sound film

For some time, attempts have been made to add sound to the film . One of the main reasons was to let the actors speak in order to be able to do without the annoying intertitles. At the world exhibition in Paris in 1900, sound and color films were shown, but the processes (e.g. hand coloring) turned out to be too expensive for commercial use. Attempts with needle tone (using a record that ran parallel to the film) were not very satisfactory either, as this was very difficult to synchronize with the film. Due to frequent film tears, a film became shorter and shorter in the course of its screening history and thus the sound offset at the end of the film increased.

In 1926 the first full-length feature film using the needle-tone technique of the Vitaphone patent premiered: "Don Juan" by Alan Crosland with Warner Oland (who later became famous as Charlie Chan ). The jazz singer by the same director first came to the cinemas in 1927 as a pin-tone film. After its overwhelming success, the film was later copied to optical sound film. With this method, a 2.54 mm wide strip is reserved for the audio track on the left edge of the image. A small lamp lights up the sound strip, which is more or less translucent depending on the volume and frequency of the sound signal. The light falls through the film onto a photocell , and the resulting fluctuations in brightness are converted into an alternating voltage for a sound signal that, after amplification, can be fed to the loudspeakers in the cinema. Through this coupling of image and sound on the same carrier medium, cracks in the film no longer posed a problem with regard to the synchronicity of the two tracks. Within just a few years, sound film replaced silent film.

Change from black and white film to color film

The first color moving pictures were taken around the year 1900. As a result, incurred by subsequent coloring of black and white films and the first color films for the cinema. The further development of color film led to productions on three-layer color film via the bipack process . The different Technicolor processes played a special role . Many color films were also made using the Agfacolor process , which the UFA in particular used for its film productions until the 1950s.

Cinema history until today

The heyday of the cinema lasted less than half a century. From the late 1950s onwards, caused not least by the increasing spread of television sets , the number of visitors to cinemas began to decline. Only in the United States did a special form of open-air cinema boom during this period, helped by the increasing motorization of the population in the post-war years : the drive-in cinema . In German cities that previously had several cinemas, the post-production theaters usually disappeared first and then other venues, until often only one cinema remained. The large halls of the remaining cinemas were later divided into several smaller halls; These rooms are mockingly referred to as “ box cinemas ”. The efforts of the film production companies to win back viewers with new performance techniques that only work when shown on a large projection surface did not show the long-term success they had hoped for. For example, a brief boom was triggered with 3D films and new widescreen technologies ( Cinerama , Todd-AO 70 mm, Cinemiracle , CinemaScope ) were experimented with, but the "dying of cinema" continued and many other cinemas gave up by the early 1980s. Then there were the competitors, video stores , computer games and, in Central Europe, private television, which was only allowed late .

Newly built cinemas since then, especially the so-called multiplex cinemas , have generally been technically well equipped with Dolby Digital and DTS sound systems (occasionally THX -certified), and in special halls also with SDDS . But even those cinemas that have survived the crisis years and, established mainly in wholesale and university towns, cinemas and local cinemas were mostly modernized box cinemas partially dismantled. Overall, the market is now consolidating at a low level.

See also

literature

Non-fiction

- Emilie Kiep-Altenloh : On the sociology of the cinema. The cinema company and the social classes of its visitors . Edition Stroemfeld, Frankfurt / M. 2007, ISBN 978-3-87877-805-9 (reprint of the Leipzig edition 1913; first scientific work on cinema at all).

- Edgar Morin: Man and the cinema. An anthropological study (“Le cinema ou l'homme imaginaire”). Ernst Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1958 (social psychological essays on film and cinema culture).

- Vincent Pinel: Louis Lumière. Inventory et cinéaste . Edition Nathan, Paris 1994, ISBN 2-09-190984-X (former title Lumière, pionnier du cinéma ).

- Hans-Jürgen Tast: Cinemas in the 1980s. Example: Berlin / West . Edition Kulleraugen, Schellerten 2008, ISBN 978-3-88842-035-1 (Kulleraugen; 35).

- Werner Biedermann: The cinema calls . The bibliophile paperbacks, Harenberg Kommunikation, Dortmund 1986, ISBN 3-88379-502-X (A cultural history of cinema advertising).

- Iris Kronauer: Pleasure, Politics and Propaganda. Cinematography in Berlin at the turn of the century . Dissertation. HU-Berlin 2000.

Contemporary

- Willy Baumann-Ammann: On the cinematograph question. Development, benefits and harms of cinematography . Zurich 1912.

- A. Wild: The fight against the cinematograph malaise . Zurich 1913.

- Adolf Sellmann: For and against cinema (with the wording of the cinema law of May 12, 1920). Schwelm 1928.

Essays

- Torsten Lorenz: The cinema in its historical development . In: Joachim-Felix Leonhard, Hans-Werner Ludwig , Dietrich Schwarze et al .: Media Studies - A manual for the development of media and forms of communication . Volume 2. W. de Gruyter, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-11-016326-8

- Helmut Merschmann: Film production in its historical development . In: Joachim-Felix Leonhard, Hans-Werner Ludwig, Dietrich Schwarze et al .: Media Studies - A manual for the development of media and forms of communication . Volume 2. W. de Gruyter, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-11-016326-8

- Ramin Rowghani: Berlin, the place of origin of film and the city of cinemas. From an original site to a big death in cinema. A very different kind of Berlin walk . In: People and Media. Journal for Culture and Communication Psychology , Berlin 2002.

- Ipse and Michael Sennhauser: Who started with the cinema? Notes on the new early history of cinema in Basel . In: Basellandschaftliche Zeitung , Liestal, January 15, 1993, p. 25.

Web links

- Current and historical cinema technology: projectors, sound systems, cross-country skiing facilities

- The early history of cinema in the style of a film

- Locked seat twice, please! A short cultural history of the cinema at Monumente Online

- Up and down of the cinema in Germany . German TV Museum Wiesbaden

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martin Loiperdinger: Film & Schokolade - Stollwerck's Businesses With Living Pictures . Stroemfeld Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Basel 1999, p. 97

- ↑ “Basically, the draft makes cinematograph theaters subject to the obligation to obtain a license. When it comes to the issue of a license, the question of needs should also be decisive for the cinemas. Permission to operate the cinema should be refused if the number of people corresponding to the conditions in the municipality has already been granted. ” The significance of the cinema amendment for homeowners . In: Vossische Zeitung , May 3, 1914, No. 222, morning edition

- ↑ The play of light in the country and the enhancement of its performances . In: Das Land , July 1, 1914, pp. 229–231

- ^ Hamburger Tageblatt , November 1, 1935

- ↑ L'Estrange Fawcett: The World of Film. Amalthea-Verlag, Zurich / Leipzig / Vienna 1928, pp. 34, 79 and 151 (translated by C. Zell, supplemented by S. Walter Fischer)

- ↑ Mexico is included in Central America in the list by continent .

- ^ Roberta Pearson: The cinema of transition. In: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (Ed.): History of the international film. Special paperback edition, Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-476-02164-5 , p. 37

- ↑ This and the following descriptions, see Fawcett, pp. 42ff

- ↑ Conversion multiplier calculated by Fredrik Matthaeis on the basis of information from the Hamburg State Archives and the Federal Statistical Office, archive link ( memento of the original from January 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c Pearson, Nowell-Smith (Ed.): Das Kino desangs , pp. 9-10

- ↑ a b c Nowell-Smith: Introduction , p. 4

- ↑ HDTV in the cinema: England fans watch match in cinema on: wikinews , June 21, 2006 (English)

- ↑ Iris Kronauer: Pleasure, Politics and Propaganda. Cinematography in Berlin at the turn of the century. Retrieved December 4, 2016 .