Sex-selective abortion

This item has been on the quality assurance side of the portal sociology entered. This is done in order to bring the quality of the articles on the subject of sociology to an acceptable level. Help eliminate the shortcomings in this article and participate in the discussion . ( Enter article )

Reason: Transferred from the general QA. See discussion: Sex-Selective Abortion # Revise .

A sex-selective abortion is an abortion that is caused by the child not being of the gender desired by the parents . Globally, this mainly affects girls ( female fetocide or prenatal femicide ), who are aborted millions of times because of their gender , especially in China and India . Various cultural, social and economic motives can be cited for this, although the surplus of men creates serious problems in these areas. The legal assessment varies significantly depending on the state; gender-selective terminations are often illegal.

In many countries in North Africa and Central and East Asia, boys are preferred to girls when giving birth. Since it has become possible to determine the sex by ultrasound examinations before birth, there has been a very large overhang of registered births of boys in China, Indian states (Punjab, Delhi, Gujarat), South Korea and the South Caucasus ( Azerbaijan , Armenia , Georgia ) found in relation to girls, which can only be explained by the (mostly illegal) targeted abortion of female fetuses. This is even shown to a lesser extent in Asian immigrants in the USA and Great Britain compared to the other population groups.

“The motives for the murder of the unborn daughter come from a very contemporary attitude - you want big weddings, big gifts and a proud son, but not an economically useless daughter. A deadly tsunami is sweeping over our girls, we are experiencing an ethical collapse in our society, but nobody gets upset. "

For doctors in India and China, abortions are a lucrative business made easier by modern technology. First introduced in 1979, the technology for prenatal gender recognition has been available there since around 2001. In recent years General Electric and Siemens have had new ultrasound devices developed that cost only a fraction of the price of devices manufactured in the West. New models can be operated mobile with solar energy in order to be more easily available nationwide.

As early as 1997, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution that "urged all states to enact and enforce laws that protect girls from all forms of violence, including the killing of newborn women and prenatal gender selection". According to Klimke, the prohibition of gender-selective abortions is part of customary international law .

Statistical research

According to the World Factbook (2019), there are 114 boys for every 100 girl births in China, 112 in Armenia and India and 110 in Hong Kong and Vietnam , Hunan and Guangdong) even 130 boys per 100 girls were born. According to the World Bank database , in 2010 there were 116.1 boys for every 100 girl births in Azerbaijan, 115.8 in China and 114.3 in Armenia.

The thesis of Amartya Sen , who addressed the problem of missing women as early as 1990, spoke of a total of 100 million missing women and warned of the socio-economic consequences. The UN estimated in 2010 that 117 million women were missing, mostly in India and China; However, these are not only due to gender-selective abortions.

It is estimated that over a million girls are aborted annually because of their gender. A statistical analysis published in 2019 that evaluated the data through 2017 estimates 23 million gender-selective abortions worldwide since 1970, with 11.9 million in China and 10.6 million in India. A statistically significant deviation from the natural gender ratio at birth was determined for 12 countries: Albania , Armenia , Azerbaijan , China , Georgia , Hong Kong , India , South Korea , Montenegro , Taiwan , Tunisia and Vietnam . The demographics researcher Christophe Guilmoto from the Institute for Development at the University of Paris-Decartes estimates that 117 million women are missing in Asia alone due to selective abortions and infanticide. A 2010 UN report found 85 million women prevented lives in China and India alone.

In addition to the practice of abortion, the countries concerned also have a long culture of killing children or infanticide , which also predominantly affects girls. The UN estimated:

“An estimated 113 to 200 million women are missing worldwide because female fetuses are specifically aborted, girls are killed as babies or cared for so poorly that they do not survive. According to the latest estimates, one million female fetuses are aborted annually in India and China alone. "

Medical background

Prenatal diagnostics

In the case of in-vitro fertilization , gender selection is medically possible (see article Preimplantation Diagnostics, Section Selection of Gender without Disease Reference ). In naturally conceived children, the earliest possible prenatal diagnosis of the child's sex is to examine the cell-free fetal DNA in the maternal bloodstream. As a result, from the seventh week of pregnancy onwards, a blood test of the mother can be used to determine the sex of the child with 98% reliability.

Transvaginal or transabdominal sonography ("ultrasound") usually determines the child's gender. In the twelfth week of pregnancy, the sonographic results with regard to sex determination are about 75% correct. After the 13th week of pregnancy, the results are almost always correct.

The sex of the unborn child can also be determined by chorionic villus sampling (“placenta puncture”) and amniocentesis (“amniotic fluid puncture”). Although these methods can be used earlier than sonography, they are invasive and therefore more risky. Since they are also more expensive, they do not play a major role in the context of gender-selective abortions.

Natural gender distribution

The human gender distribution at birth is around 105 boys for 100 girls. If there are more than 108 boys for every 100 girls, a selective abortion of girls can be assumed, with fewer than 102 boys a selection of boys. Some authors already conclude that there is a deviation of 105–107 boys in terms of gender-selective abortions. On the other hand, natural fluctuations in the gender distribution are cited, the influence of which has not yet been sufficiently clarified. Projections based on the gender distribution at birth on the number of aborted girls are therefore subject to a certain degree of uncertainty.

Situation in asia

India

101-103 103-107 ... 125–130 boys

average across India: 110 boys

across India ø under 7 years: 109 boys

Total Indian population: 106 male

In India , significantly more female fetuses are aborted than males: According to the 2011 census, there were only 914 girls for every 1000 boys (47.75% = 109 boys for 100 girls) - in 2001 there were 927 girls (48.11%, 108 : 100; each under 7 years). In the total population in 2011 there were 940 female Indians for every 1000 male (48.45%, 106: 100) - in 2001 there were 933 female (48.27%, 107: 100).

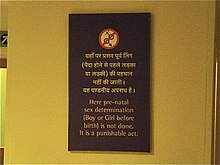

In 1994, the Indian Parliament banned prenatal gender recognition and made it a criminal offense with the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act . Deepak Dahiya, the former health department head of the state of Haryana , in which a particularly large number of girls were aborted, worked very hard for the implementation of the law. He took 30 doctors who had illegally performed ultrasound scans to court between 2001 and 2005. The girl births in Haryana picked up because of the crackdown. However, since Dahiya's retirement in 2005, femicide has increased again as there is no longer any apparent political will to enforce the law.

In India there are also economic reasons for the murder of daughters. Even earlier, a daughter was a burden because of the high “trousseau” that was due when she married (see dowry murders ); today there are also school and education costs. In the early 1990s, abortion clinics advertised in public spaces with the slogan “Pay Rupees 500 now or 50,000 in eighteen years!”, With the comparatively low price for an abortion being compared with the much higher dowry for a daughter that was customary at the time. However, gender selection in India cannot be attributed solely to a lack of economic resources. “Rather, an increase in child murders can be observed in the wealthier classes in particular, which was triggered by growing materialism. So far, progress and modernization have not been able to counteract the deeply rooted desire for male successors. "

China

The " one-child policy " introduced in 1979/1980 increased the desire of many parents for male offspring considerably. Cultural reasons seem to be essential for this, something that boys carry on with the family name. In China, according to patriarchal tradition, women belong to the husband's family; According to an old Chinese proverb, women are "like water that is thrown away". In China, the State Commission for Health Care and Family Planning is responsible for abortion policy and its implications. Its chairperson, Li Bin , promised in 2012 that a greater gender balance would be achieved in the next five-year plan. Effective measures have not yet been taken.

Pakistan

The data situation is particularly unclear for Pakistan. Abortions are largely illegal due to Islamic legislation, but often take place under precarious conditions. The less widespread use of ultrasound devices makes prenatal sex selection impossible. However, the killing of newborn girls in Pakistan, which is documented as early as the 19th century, is common. In 2010, for example, in the major cities of Pakistan alone, 1210 babies, often dumped in garbage dumps, were documented, "90% girls."

South Korea

In South Korea, gender-selective abortion of girls was common from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s. In 1991 there were around 119 boy births for every 100 girls. In the 1990s, the government began a campaign to raise awareness of the negative consequences of the discriminatory shift between the sexes and to implement the ban on gender-selective abortions more effectively. Along with the general economic and socio-cultural development (industrialization, urbanization, promotion of the education of women, state pension system, so that parents are less dependent on earning sons for their retirement provisions), the number of gender-selective abortions has fallen considerably since then.

Situation in Europe

Southeast Europe

A Council of Europe resolution of November 2011 stated that “prenatal gender selection has reached worrying proportions”. Albania, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia are reprimanded for this and called for measures to counteract the gender selection of girls and the lack of equality. A statistical study of the states of the former Soviet Union in 2013 calculated for Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia that 10% too few girls are born there. For example, among the first-born children in Armenia there were 138 boys for every 100 girls; if the first-born is a girl, there were 154 boys for every 100 second-born girls.

Because abortion is assigned to the health sector and not to human rights policy, there is currently no legal basis in the European Union to take action against the abortion practice among EU candidates in the Balkans.

Sweden

In 2009, the Swedish National Health and Welfare Council, Socialstyrelsen , explicitly stated that gender-selective abortions should not be rejected. Every pregnant woman has the right to an abortion up to the 18th week without giving a reason ( SFS 1974: 595), whereby the determination of the sex is not restricted before this period.

Germany

In Germany, according to § 15 Art. 1 GenDG , the gender may only be communicated after the 12th week of pregnancy; Later abortions are only exempt from punishment under certain indications.

Situation in Africa

In many African countries, sons are preferred and gender-selective abortions occur when the necessary technology is available. In a 2019 study, Tunisia appears as the only African country with a statistically significant excess of girls in the sex proportions of those born. In most African countries the sex proportions of those born are balanced or even proportionally more girls are born. Most African countries have restrictive abortion laws; in addition, fertility rates (number of children per woman) are often high.

Situation in North America

In the United States of America , especially in Asian immigrant families, there is a preference for male offspring and gender-selective abortions, which have been explicitly prohibited in individual states. But there is no reliable data. A draft law on the nationwide ban on gender-selective abortions failed in the House of Representatives in 2012.

In Canada , where there are currently no legal restrictions on abortions, but the gender ratio of the births is overall balanced, a bill for a Sex-selective Abortion Act is currently being discussed in parliament (February 26, 2020), which will make sex-selective abortion a criminal offense should. Selective abortions of girls are also suspected in Asian immigrant families.

Situation in South America

In Latin America, there are no known abnormalities in the gender ratio of the born; A 2013 study found no evidence of sex-selective abortions in poor regions of Brazil when ultrasound examinations became available to pregnant women.

Ethical evaluation

The ethical controversy with regard to abortion and human rights concerns in particular the relationship between female self-determination (of pregnant women) and female discrimination (of unborn girls) or of civil liberties and patriarchal attitudes. The legitimacy of gender selection in bioethics is also being discussed in (western) countries without a clear trend regarding the preferred gender of children.

consequences

According to some experts, the global consequence of selective abortions threatens the greatest gender imbalance in human history this century. Demography researcher Christopher Guilmoto calls this development an "alarming masculinization" of the world. The economist Jayati Ghosh from Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi sees the long-term shortage of female labor as an acute threat to growth in the world's most dynamic economies in Asia.

According to sociologists, the lack of women could be a future cause of social violence and war. The plus of men and the accumulation of capital can lead to increased militarization. The Swiss MP in the Council of Europe Doris Stump also warns of an increase in trafficking in women , prostitution and violence in families. In the future, politicians in China will have to find ways of stabilizing a social system in which a large number of young men will remain with no prospect of reliable social ties. According to forecasts, fifteen to twenty percent of men of marriageable age could not find a partner. In China, 97% of these men have no high school diploma; across cultures, violent crimes are mostly committed by young, unmarried men of low status. Another consequence of this development is the kidnapping of women today. At job fairs, young migrant workers are kidnapped who are later sold to bachelors. It is reported of women from Vietnam, Myanmar and North Korea being trafficked into mainland China for forced marriages .

See also

literature

- Daniel Goodkind: Sex Selective Abortion . In: James D. Wright (Ed.): International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition) . Elsevier , Amsterdam 2015, ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5 , pp. 686-688 , doi : 10.1016 / B978-0-08-097086-8.31038-8 (English).

- World Health Organization (Ed.): Preventing gender-biased sex selection . An interagency statement OHCHR, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women and WHO. 2011, ISBN 978-92-4150146-0 (English, unfpa.org [PDF; accessed April 25, 2020]).

- Mara Hvistendahl : The Disappearance of Women. Selective Birth Control and the Consequences. dtv, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-423-28009-9 .

- Laura Rahm: Gender-Biased Sex Selection in South Korea, India and Vietnam . Assessing the Influence of Public Policy (= Demographic Transformation and Socio-Economic Development . Volume 11 ). Springer, 2020, ISBN 978-3-03020233-0 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-030-20234-7 .

- Sharada Srinivasan, Shuzhuo Li (Ed.): Scarce Women and Surplus Men in China and India . Macro Demographics versus Local Dynamics (= Demographic Transformation and Socio-Economic Development . Volume 8 ). Springer, 2018, ISBN 978-3-319-63274-2 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-319-63275-9 .

- Isabelle Attané: The Demographic Masculinization of China . Hoping for a Son (= INED Population Studies . Volume 1 ). Springer, 2013, ISBN 978-3-319-00235-4 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-319-00236-1 .

- Isabelle Attané, Christophe Z. Guimoto (Ed.): Watering the Neighbor's Garden. The Growing Demographic Female Deficit in Asia . Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography, Paris 2007, ISBN 2-910053-29-6 (English, cicred.org [PDF; accessed April 23, 2020] proceedings).

Web links

- United Nations Population Fund : Gender-biased sex selection .

- World Health Organization : Sex Selection and Discrimination .

- Savethegirlchild.org initiative

Individual evidence

- ↑ Overview in Therese Hesketh & Zhu Wei Xing (2006): Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: Causes and consequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA Vol. 103 No. 36: 13271-13275. doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0602203103 (open access)

- ↑ The Death of the Unborn Girl in the Caucasus. In: www.welt.de. December 12, 2013, accessed November 3, 2019 .

- ↑ James FX Egan, Winston A. Campbell, Audrey Chapman, Alireza A. Shamshirsaz, Padmalatha Gurram, Peter A. Benn (2011): Distortions of sex ratios at birth in the United States; evidence for prenatal gender selection. Prenatal Diagnostics 31: 560-565. doi: 10.1002 / pd.2747

- ^ Sylvie Dubuc & David Coleman (2007): An Increase in the Sex Ratio of Births to India-born Mothers in England and Wales: Evidence for Sex-Selective Abortion. Population and Development Review 33 (2): pp. 383-400.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Georg Blume: The murderous blemish woman. Die Zeit , March 15, 2012, p. 4 , accessed on May 7, 2013 .

- ↑ Chu Junhong: Prenatal Sex Determination and Sex-Selective Abortion in Rural Central China . In: Population and Development Review . 27, No. 2, 2001, p. 260. doi : 10.1111 / j.1728-4457.2001.00259.x .

- ↑ Resolution 51/76 of the UN General Assembly (UN General Assembly: Resolution on the girl child , A / RES / 51/76 ) of February 20, 1997, (English) , (German, copy in advance) . Very similar to B. Resolution 7/29 of the UN Human Rights Council (UN Human Rights Council: Rights of the child , HRC / RES / 7/29 ) of March 28, 2008, 24b.

- ^ Romy Klimke: Harmful traditional and cultural practices in international and regional human rights protection (= Armin von Bogdandy, Anne Peter [Hrsg.]: Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, Contributions to Foreign Public Law and International Law . Volume 281 ). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58756-0 , pp. 485 f ., doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-662-58757-7 .

- ↑ a b The Wold Bank DataBank, Gender Statistics , Sex ratio at birth. (Select 0.0000 under "Layout", "Format Numbers", "Precision"!)

- ↑ Sex ratio . In: Central Intelligence Agency (ed.): The World Factbook .

- ↑ China faces growing sex imbalance. BBC News , January 11, 2010, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ^ Xinhua: China's sex ratio declines for two straight years. english.news.cn, August 16, 2011, archived from the original on February 22, 2015 ; accessed on April 18, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Kang C, Wang Y. Sex ratio at birth. In: Theses Collection of 2001 National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Survey. Beijing: China Population Publishing House, 2003, pp. 88-98.

- ↑ Poston, Dudley L Jr. et al .: China's unbalanced sex ratio at birth, millions of excess bachelors and societal implications . In: Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies . tape 6 , no. 4 , 2011, p. 314-320 , doi : 10.1080 / 17450128.2011.630428 (English).

- ↑ UNFPA Asia and the Pacific Regional Office (ed.): Sex Imbalances at Birth . Current trends, consequences and policy implications. 2012, ISBN 978-974-680-338-0 (English, demographie.net [PDF; accessed April 25, 2020]).

- ^ Tania Branigan: China's Great Gender Crisis. The Guardian , November 2, 2011, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ See Amartya Sen : More than 100 million women are missing , New York Review of Books, pp. 61–66.

- ↑ a b Chao, Fengqing; Gerland, Patrick; Cook, Alex R .; Alkema, Leontine: Systematic assessment of the sex ratio at birth for all countries and estimation of national imbalances and regional reference levels . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 116, No. 19, May 7, 2019, pp. 9303-9311. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1812593116 . PMID 30988199 . PMC 6511063 (free full text).

- ↑ Strong women - strong children (2007), information from unicef.de .

- ↑ Devaney SA, Palomaki GE, Scott JA, Bianchi DW: Noninvasive Fetal Sex Determination Using Cell-Free Fetal DNA . In: JAMA . 306, No. 6, 2011, pp. 627-636. doi : 10.1001 / jama.2011.1114 . PMID 21828326 . PMC 4526182 (free full text).

- ↑ Michelle Roberts: Baby gender blood tests 'accurate' . In: BBC News Online , August 10, 2011.

- ↑ Mazza V, Falcinelli C, Paganelli S, et al: Sonographic early fetal gender assignment: a longitudinal study in pregnancies after in vitro fertilization . In: Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol . 17, No. 6, June 2001, pp. 513-6. doi : 10.1046 / j.1469-0705.2001.00421.x . PMID 11422974 .

- ↑ Alfirevic Zarko, of Dadelszen P .: Instruments for chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis . In: Cochrane Database Syst Rev . No. 1, 2003, p. CD000114. doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD000114 . PMID 12535386 .

- ^ Report of the International Workshop on Skewed Sex Ratios at Birth United Nations FPA (2012).

- ↑ Census of India 2011 : Sex Ratio of Total population and child population in the age group 0-6 and 7+ years: 2001 and 2011. Delhi 2011 (English; PDF: 9 kB, 1 page on censusindia.gov.in ( Memento of April 9, 2011 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ Pre-Conception & Pre-Natal. Diagnostic Techniques Act, 1994 and Rules with Amendments Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India.

- ↑ Slogan quoted in Mala Sen: Death by Fire. Sati, Dowry Death and Female Infanticide in Modern India, London 2001, p. 187; see. Romy Klimke: Harmful traditional and cultural practices in international and regional human rights protection (= Armin von Bogdandy, Anne Peter [Hrsg.]: Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, Contributions to Foreign Public Law and International Law . Volume 281 ). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58756-0 , pp. 105-107 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-662-58757-7 .

- ↑ Slogan quoted in Mala Sen: Death by Fire. Sati, Dowry Death and Female Infanticide in Modern India, London 2001, p. 187; see. Romy Klimke: Harmful traditional and cultural practices in international and regional human rights protection (= Armin von Bogdandy, Anne Peter [Hrsg.]: Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, Contributions to Foreign Public Law and International Law . Volume 281 ). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58756-0 , pp. 107 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-662-58757-7 . This applies, for example, to Haryana and Punjab , both of which are rich states with farmers and large landowners, cf. Mala Sen: Death by Fire. Sati, Dowry Death and Female Infanticide in Modern India, London 2001, p. 271.

- ↑ See Renate Syed: "A misfortune is the daughter". Discrimination against girls in India of old and now . Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 978-3-447-04334-2 , pp. 66 .

- ↑ AFP: Infanticide on the rise: 1,210 babies found dead in 2010, says Edhi - The Express Tribune. In: Tribune. January 28, 2011, accessed April 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Christina Hitrova: Female Infanticide and Gender-based Sex-selective Foeticide . In: Laurent / Platzer / Idomir (eds.): Femicide. A global issue that demands action . Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-200-03012-1 , p. 74–77 , 77 (English, genevadeclaration.org [PDF; accessed April 21, 2020]).

- ↑ Pliillan Joun: Ethical Problems of Selective Abortion . The discussion in South Korea. Ed .: Center for Medical Ethics Bochum (= medical ethical materials . Issue 147). 2004, ISBN 3-931993-28-0 ( ruhr-uni-bochum.de [PDF; accessed April 25, 2020]).

- ^ Resolution 1829 (2011) Prenatal sex selection. (No longer available online.) Council of Europe , October 3, 2011, archived from the original on October 30, 2013 ; accessed on May 13, 2013 .

- ^ Marc Michael et al .: The mystery of missing female children in the Caucasus . An analysis of sex ratios by birthorder. In: International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health . tape 39 , no. 2 , 2013, ISSN 1944-0391 , p. 97-102 , doi : 10.1363 / 3909713 (English).

- ↑ Sweden rules 'gender-based' abortion legal. The Local, May 20, 2009, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ^ Susanne Kummer: Genderzid . Targeted abortion of girls - a global problem. In: Imago Hominis . tape 20 , no. 1 , 2013, p. 10-12 ( imabe.org [accessed April 18, 2020]).

- ↑ Holger Dambeck: Abortions: Doctors should keep the sex of fetuses secret. Spiegel Online , September 13, 2011, accessed April 29, 2020 .

- ↑ James FX Egan et al .: Distortions of sex ratios at birth in the United States; evidence for prenatal gender selection. In: Prenat Diagn 2011; 31: 560-565. March 27, 2011, accessed May 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Jennifer Steinhauer: House Rejects Bill to Ban Sex-Selective abortions. The New York Times , May 31, 2012, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Parliament of Canada: Bill C-233 (First Reading), February 26, 2020, on parl.ca , accessed April 29, 2020.

- ↑ Lauren Vogel: Sex selection migrates to Canada . In: CMAJ . tape 184 , no. 3 , 2012, p. E163 – E164 , doi : 10.1503 / cmaj.109-4091 (English).

- ↑ Chiavegatto Filho, ADP, Kawachi, I .: Are sex-selective abortions a characteristic of every poor region? Evidence from Brazil . In: Int J Public Health . tape 58 , 2013, p. 395-400 , doi : 10.1007 / s00038-012-0421-6 .

- ↑ Irmgard Nippert: Perspectives on gender selection . In: Wolfgang van den Daele (Ed.): Biopolitics (= Leviathan . Volume 23 ). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 978-3-531-14720-8 , p. 201-233 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-322-80772-4_8 .

- ↑ Sebastian Schnettler, Andreas Filser: Demographic masculinization and violence . A research report from an evolutionary and social science perspective. In: Gerald Hartung, Matthias Herrgen (Ed.): Interdisciplinary Anthropology . Yearbook 2/2014: Violence and Aggression. Springer, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-07409-8 , pp. 130-142 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-658-07410-4_10 .

- ^ Therese Hesketh, Li Lu, Zhu Wei Xing: The consequences of son preference and sex-selective abortion in China and other Asian countries . In: CMAJ . tape 183 , no. 12 , September 6, 2011, p. 1374-1377 , doi : 10.1503 / cmaj.101368 (English).

- ↑ Angela Köckritz, Elisabeth Niejahr: China: The loneliness of many. In: Zeit Online. November 17, 2012, accessed June 24, 2015 (No. 46/2012).

- ↑ Jonathan V. Last: The War Against Girls. The Wall Street Journal , June 24, 2011, accessed June 24, 2015 .