Glasgow Subway

| Glasgow Subway | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Basic information | |

| Country | Great Britain |

| city | Glasgow |

| opening | 1896 |

| operator | Strathclyde Partnership for Transport |

| owner | Transport Scotland |

| Infrastructure | |

| Route length | 10.5 km |

| Gauge | 1,219 mm |

| Power system | 600 V = , power rail |

| Stations | 15th |

| operation | |

| Lines | 1 |

| statistics | |

| Passengers | 34 950 per day (2013/14) |

| website | |

| spt.co.uk/Subway | |

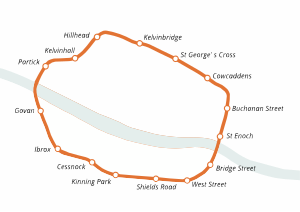

Route plan with the 15 stations |

|

The Glasgow Subway is the underground for the largest Scottish city, Glasgow . Opened in 1896, it was the fourth oldest underground system in the world after the London , Liverpool and Budapest subways. It only consists of a ring section running completely in the tunnel and has never been expanded since it was opened. It is operated by the Strathclyde Partnership for Transport (SPT) and, together with the suburban lines of the railway, forms the high-speed rail network in Glasgow.

Route and operation

The 10.5 kilometer long ring route with 15 stations runs completely underground, only the depot at Govan , in the southwest, is on the surface. It connects downtown Glasgow with the West End and the southwestern suburbs south of the River Clyde . The route is used by trains on two lines running in opposite directions. It is operated in left-hand traffic , the journeys on the outer ring track ( outer circle ) with the identification color orange are clockwise , those on the inner ring track ( inner circle ) with the identification color gray counterclockwise. The trains run on weekdays between 6:30 a.m. and 11:30 p.m. at intervals of four to eight minutes, on Sundays from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. every eight minutes.

The vehicles run on narrow-gauge tracks with the unusual track width of 1219 millimeters or four feet . The trains get their electricity from a busbar on the side with a voltage of 600 volts . The tunnels with a diameter of only 3.35 meters are often just below the surface of the earth, they often follow the course of the road. Those sections of the route that cross under the rivers Clyde and Kelvin or railway lines are lower and are clad with cast iron segments. They make up about a third of the route. The tunnel walls in both directions of travel are around 0.75 to 1.8 m apart. The route has gradients of up to six percent. The deepest station is Buchanan Street, which is twelve meters below the surface.

story

First plans and concepts

As early as 1887, when Glasgow was able to benefit from the economic boom due to trade between Europe and America since the 18th century, different plans were put forward, according to which the increasing traffic volume on the surface should be relieved by an underground railway. Three years later, the Glasgow District Subway Company's conception of a subway ring received approval. A 9.5 meter wide shaft was created within seven months, which was to be the starting point for further tunnel construction. Water-rich sands slowed down construction progress to just 20 centimeters per week. However, since the majority of the tunnel sections should follow the course of the road on the surface, the cover construction or open construction method could be used, in which the tunnels are excavated on the surface and the road surface is reapplied at the end of the construction work ( under-paving ). The lower-lying sections, especially when crossing under the rivers and the railway lines, were constructed using the shield tunneling method , with shields according to Greathead , hydraulic jacks for tunneling and overpressure to prevent water ingress. If you hit layers of rock , you blasted it with dynamite in order to achieve the desired route.

Beginnings as a cableway

On December 14, 1896 , the Glasgow subway opened. The operation of the Glasgower U-Bahn as a cable car differed fundamentally from the underground railways built up to then and later. The operation took place over two continuously running hauling cables, each by a 1500 hp strong steam engine was driven in a dedicated power plant. The two-car trains had a clamp in the leading car that was manually operated by the driver and that encompassed the pulling rope. If the train stopped in a station, he had to open the clamp so that the train was no longer connected to the rope and came to a stop. The 38 millimeter thick steel cables were each 11 kilometers long, weighed 57 tons and ran over 1,700 guide rollers. At the southern end of the machine house stood the steam boiler with eight individual coal boilers. The cables were led from the machine room into a 58-meter-long tensioning room, in which the tension of the pulling ropes was kept constant despite the thermal expansion and stretching of the rope with tension washers.

The Subway Company chose this costly drive method because cable trams were already in use in Edinburgh and Glasgow. In addition, there was no belief in electric train operation in the tunnel; the City and South London Railway, the first electrically operated underground railway, had not yet opened at the time of planning. On the other hand, the cable drive meant that larger inclines of up to 6.25% inclination could be realized at the river crossings, which reduced the construction costs.

Despite its satisfactory operation, the system as a cableway was uneconomical: the worn drive cables soon had to be replaced, which meant an enormous financial burden for society. Poor station lighting deterred many people from using the subway instead of the parallel tram. At the same time, the underground operation required more personnel than the tram electrified in 1901. The low income from passenger transport with simultaneous cost burdens led to the economic ruin of the operating company, so that the subway ring came into the ownership of the city's own Glasgow City Corporation as early as 1922 through a cheap purchase . This decided the subsequent electrification of the railway, which was completed in 1935.

New start after electrification of the subway

In 1935, after a break of thirteen years, the subway was resumed, but now as an electric subway. The travel time on the entire ring could be reduced from 39 to 28 minutes. The railway was officially renamed Underground , which was not accepted by the population. In 2003 it got its old name back, Subway .

The two ring sections were equipped with side busbars for 600 V direct current. No new vehicles were purchased for electrical operation. The existing cars were lengthened, they received bogies instead of the two single axles and lateral pantographs . It emerged railcars with motorized bogies and non-motorized sidecar that will subsequently reversed as a two-car trains with leading running railcars.

Two additional power rails, which were attached to the sides of the tunnel walls facing away from the platforms, ensured the power supply of the interior lighting with 220 V alternating current. They were at the level of the side windows of the cars, the current was tapped by pantographs attached to the side of the train ends. This solution was chosen because the tunnel walls had shifted so far in some places that there was no longer a uniform clearance profile and a second lateral conductor rail at the level of the tracks was therefore not possible. The separate power supply was inter alia. Necessary because the trains were parked, serviced and cleaned on the tracks at night with the power switched off.

The operating performance increased continuously, but was delayed as a result of the Second World War , a bomb attack in 1940 even caused the temporary cessation of operations for around half a year. In the period that followed, the subway went through times of increases and decreases in passengers. In the 1950s, a three-car train was used for the first time to alleviate the overcrowding of the trains. The constant use of such trains did not take place until the 1980s, however, as the acquisition costs for the new vehicles were high. Fluorescent tubes replaced the incandescent lamps that were used until the 1960s . Despite these advances, the equipment was now out of date and unattractive, so a major overhaul of the system was warranted. As a result of this, the Greater Glasgow Passenger Transport Executive (GG PTE) was formed in 1973 . In 1975 responsibility passed to the Strathclyde Regional Council , which ceased operations in 1977 and then carried out a general renovation.

The last day of operation of the old trains was May 21, 1977. On that day, traffic was prematurely interrupted around noon because a crack had been discovered on a tunnel wall. The planned celebrations on the occasion of the last week of operation were therefore canceled, but a last train with prominent passengers drove again on May 25, 1977. It ran from Bridge Street to Cessnock station without crossing under the Clyde. To get to Bridge Street station, the train used the outer ring in the opposite direction as an exception.

Modernization program and reopening

The renovation began in 1977 and lasted almost three years, during which time the entire ring was not in operation. The renovation program included several aspects with the aim of creating a modern means of transport. All train stations were rebuilt and modernized, and additional side or central platforms were built in six stations. 28 escalators were installed in nine stations, new vehicles with greater comfort and passenger capacity were put into operation and an automated ticket system was introduced. The line received new safety technology and a sewage system, the superstructure was designed as a solid track to dampen structure-borne noise, the tunnel walls were newly clad and an above-ground depot system was built with a connection to both tracks.

Until then there was no connection between the two track rails even for depot Broomloan depot between stations Ibrox and Govan. The wagons had to be lifted there with a crane through a shaft and into the tunnel. Since the line had no sidings until the renovation, the trains had to be parked on the tracks overnight. This situation had the consequence that the same cycle had to be driven all day. The modernization program thus also brought operational advantages.

The subway was reopened on April 16, 1980. The new orange-colored cars drove through the ring route in 22 minutes instead of the previous 28 minutes. The frequency could be adjusted during the day according to demand: six minutes during normal times and four minutes during rush hour. Compared to 1977, the workforce was reduced by 28%, a standard fare (25 pence for adults, 15 pence for children) was introduced.

Stations

The tracks between the stations lie entirely in separate tunnels with a diameter of 3.35 meters, and since the modernization there has been a track connection at the two entrances to the depot. Until then, all stations had three-meter-wide central platforms with only one exit. Before they were renamed Subway , the stations were labeled “U NDERGROUN D” for 68 years . The signs to the stations were round, they showed a red U on a white background.

During the total closure between 1977 and 1980, some stations were heavily changed.

- Buchanan Street: The main station in the city center is connected to the neighboring long-distance and suburban railway station, Glasgow Queen Street , via a pedestrian tunnel . It was given an additional side platform at the Outer Circle , and since 2005 a glass wall has separated the middle platform from its platform for safety reasons.

- Govan (formerly Govan Cross): The station is a transfer point to several bus lines , because of the high volume of traffic it was completely rebuilt and got two side platforms instead of the central platform.

- Hillhead: With the addition of a side platform at Outer Circle , the most important station in the West End has been adapted to the high traffic volume caused by the nearby university .

- Ibrox (formerly Copland Road): Due to its proximity to the stadium of the Glasgow Rangers football club , the station received an additional side platform at the Outer Circle .

- Partick: The station replaced the previous Merkland Street station in 1980, it received two side platforms. The platforms of the suburban railway station of the same name have also been moved to make it easier to change trains.

- St Enoch: The station was originally located directly in front of the long-distance train station of the same name , which was demolished in 1977. To the west of this is the Glasgow Central train station within walking distance, with the option of changing to the suburban train. The former access building was retained, but it was given a different purpose and replaced by a modern, functional building. To the central platform, which is only used by the Inner Circle , an eastern side platform was added for the clockwise direction of travel.

The former Partick Cross station is now called Kelvinhall. The Kelvinbridge station was connected to the bridge over the River Kelvin by long escalators .

vehicles

First generation vehicles

The cable car cars were lengthened in the course of electrification and were given bogies instead of single axles. The resulting vehicles were 12.8 meters long, they had 42 seats, which were arranged lengthways. The railcars received traction motors and pantographs, they each operated with an attached sidecar. At the end of the car there were initially lattice doors on the platform side, which were largely replaced by massive sliding doors. The initially two-tone vehicles were later painted red, car 32 was given a unique double-leaf sliding door in the middle of the car. It ran as an intermediate car in a test train consisting of three vehicles, later it was used as a normal sidecar.

Museum vehicles

As a result of the changed clearance profile, wagons of the first generation can no longer run on the route.

Cars 39 and 41 were taken back to their original form after being taken out of service in 1977. In doing so, they were shortened to the original dimensions, and the bogies were replaced by individual axles. In the Glasgow Transport Museum until 2010, a replica of a station, cable car cars and first-generation railcars were on display, and since 2011 the exhibits have been in the local Riverside Museum .

Current fleet of vehicles

As part of the modernization program, 33 new railcars were purchased (as of 1981), and there are also eight sidecars. The railcars are 12.81 meters long, 2.34 meters wide and, with a floor height of 0.695 meters, 2.65 meters high, resulting in an interior height of less than two meters. They have 36 seats and 54 standing places. A maximum of three-car units can be put together with the existing vehicles. The four electric motors of a railcar together achieve 142 kW and can accelerate it to a top speed of 54 km / h.

The trains run automatically, the driver's tasks are limited to closing the doors and starting the train. Some of them have the original orange paint, and some are painted in the colors of the SPT. To mark the centenary of the railway, car 122 was given a white / brown livery similar to that of the first cable car cars, and a light blue sidecar advertises the 2014 Commonwealth Games in the city .

Further modernization of the vehicle fleet

17 new trains were ordered from Stadler in 2016 for around £ 200 million. They are 39 meters long, have 116 permanent seats, twelve folding seats and standing room for 204. The continuously accessible trains consist of four car bodies with six bogies, the two intermediate car bodies with only one bogie are attached to the end cars. At the beginning of May 2019, the first train arrived in Glasgow for testing. The subway is to be converted to fully automatic operation with platform screen doors in the following years .

Web links

- Strathclyde Partnership for Transport (SPT; operator of the Glasgow Subway) (English)

- Information about the Glasgow Subway (private )

- Glasgow District Subway at railbrit.co.uk (English)

- Network and track plan at the Department of Transport Studies at the University of Westminster

- The Glasgow UndergroundD / Subway at dewi.ca with many historical photos

- Architectural photo series over all stations of the Glasgow Subway (as of 03/2014)

literature

- Walter J. Hinkel, Karlreiber, Gerhard Valenta, Helmut Liebsch: U-Bahn - yesterday-today-tomorrow - from 1863 to 2010 . NJ Schmid, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-900607-44-3

- Daniel Bennett: Metro. The history of the subway . Transpress, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-613-71262-8

- Daniel Riechers: Metros in Europe . Transpress, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-344-71049-4

- George Watson: Glasgow Subway Album . Adam Gordon, Chetwode 2000, ISBN 1-874422-31-1 .

- Robert Schwandl: Metros in Britain . 1st edition. Robert Schwandl, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-936573-12-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Subway at spt.co.uk, accessed on May 28, 2017

- ↑ a b Robert Schwandl: Metros in Britain . 1st edition. Robert Schwandl, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-936573-12-3 , pp. 150 .

- ^ The Glasgow District Subway . In: Cassier's Magazine . 1898 ( online [accessed November 24, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d Robert Schwandl: op. Cit. , P. 151.

- ↑ a b c d Robert Schwandl: op. Cit. , P. 152.

- ↑ George Watson: Glasgow Subway Album . Adam Gordon, Chetwode 2000, ISBN 1-874422-31-1 , pp. 50 .

- ↑ George Watson: op. Cit. , P. 6.

- ↑ a b Glasgow's Unique Underground Railways (English) at mikes.railhistory.railfan.net, accessed on November 6, 2014

- ↑ George Watson: op. Cit. , Pp. 28 and 36.

- ↑ Glasgow Underground - Old and New in: Stadtverkehr 10/1981, p. 416.

- ↑ The Glasgow UndergroundD / Subway: Above Ground at dewi.ca, accessed November 7, 2014

- ↑ George Watson: op. Cit. , P. 51.

- ↑ Robert Schwandl: op. Cit. , P. 155.

- ↑ Robert Schwandl: op. Cit. , P. 153.

- ↑ Robert Schwandl: op. Cit. , P. 154.

- ↑ George Watson: op. Cit. , P. 30.

- ↑ George Watson: op. Cit. , P. 23.

- ↑ George Watson: op. Cit. , P. 50.

- ↑ Glasgow District Subway at railbrit.co.uk (English), accessed on November 6, 2014

- ↑ Blickpunkt Tram 6/2018, p. 151 f.

- ↑ First underground train delivered for Glasgow in: Tram Magazin 7/2019, p. 12 f.

- ↑ Eisenbahn-Revue International, edition for Germany, issue 5/2016, page 244.