Gorgosaurus

| Gorgosaurus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

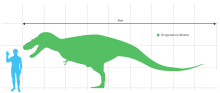

Skeletal reconstruction of Gorgosaurus |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Cretaceous (late Campanium ) | ||||||||||||

| 76.4 to 72 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Gorgosaurus | ||||||||||||

| Lambe , 1914 | ||||||||||||

| Art | ||||||||||||

|

Gorgosaurus ( Greek : "impetuous lizard", from γοργός gorgos "impetuous, terrible" and σαῦρος sauros "lizard") was a theropod dinosaur from the family of Tyrannosauridae , which lived about 76 to 72 million years ago in the Upper Cretaceous (late Campanium ) lived in western North America. Fossil remains have been discovered in the Canadian province of Alberta and possibly in the US state of Montana . At the momentonly one species is recognizedof this genus , the type species Gorgosaurus libratus .

Like most known tyrannosaurids, Gorgosaurus was a bipedal carnivore that weighed more than a ton as an adult and carried dozens of large, sharp teeth in its jaw, while the two-fingered arms were relatively small. Gorgosaurus was closely related to the very similar Albertosaurus ; both genera are separated only on the basis of slight differences in the teeth and cranial bones. Some experts consider Gorgosaurus libratus to be a species of Albertosaurus - in this view, Gorgosaurus would be a juvenile synonym of this genus.

Gorgosaurus lived in a lush floodplain along the Western Interior Seaway , an arm of the sea that divided North America in half in the Upper Cretaceous. As a top predator , Gorgosaurus was at the top of the food chain and believed to hunt the common ceratopsids and hadrosaurids . In some areas, Gorgosaurus lived with Daspletosaurus , another tyrannosaurid. Although these animals were roughly the same size, there is evidence that both genera occupied different ecological niches . Gorgosaurus is the most frequently found tyrannosaurid - the numerous fossils allow scientists to draw conclusions about the biology of tyrannosaurids, for example about individual development ( ontogenesis ).

description

Gorgosaurus reached about the size of Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus . Adults were eight to nine meters long and probably weighed more than 2.4 tons. The largest skull found measures 99 centimeters long and is therefore only slightly smaller than that of Daspletosaurus , a tyrannosaurid that lived in the same area at the same time . As with other tyrannosaurids, the skull was large in relation to the body, with chambers in the skull bones and large skull openings ( skull windows ) reducing its weight. Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus have relatively longer and flatter skulls than Daspletosaurus and other tyrannosaurids. The end of the snout was blunt and the pair of nasal bones and the pair of parietals were fused along the center line of the skull, as in all other members of the family. The eye socket (orbital window) was round and thus differed from the oval to keyhole-like shapes in other tyrannosaurids. Similar to Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus , a high crest extends from the tear bone (lacrimale) in front of each eye . Gorgosaurus is distinguished from Albertosaurus by differences in the bones that surround the brain.

The teeth of Gorgosaurus were typical of all known tyrannosaurids. The eight teeth of the intermaxillary bone (premaxillary) at the front end of the snout were small, tightly packed and “D” -shaped in cross-section compared to the rest of the teeth. The rest of the teeth were oval in cross-section and not blade-shaped like most other theropods. In addition to the eight teeth of the intermaxillary bone , Gorgosaurus had 26 to 30 teeth in the upper jaw and 30 to 34 teeth in the lower jaw. Gorgosaurus has about as many teeth as Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus , but fewer than Tarbosaurus or Tyrannosaurus .

As with all tyrannosaurids, the design of Gorgosaurus is characterized by a large head that sits on an "S" -shaped neck. In contrast to the large head, the arms were very small. The hands had only two fingers and claws, although a third limb in the metacarpus was found in some finds - a rudiment of the third finger as possessed by other theropods. The hind legs of the tyrannosaurids were longer in relation to the body than other theropods. The longest thigh bone (femur) known from Gorgosaurus measures 105 centimeters. In several smaller specimens but that was shin (tibia) longer than the femur - a ratio, such as is found frequently at fast-running animals. The two bones in the largest skeletons found were about the same length.

According to the first description of Yutyrannus in 2012, a large and very closely related species that was completely feathered, it is certain that Gorgosaurus was also dressed in a soft fluff of down feathers.

Systematics

Within the Tyrannosauridae, Gorgosaurus belongs to the subfamily Albertosaurinae - together with the closely related, geologically somewhat younger Albertosaurus . These two genera are the only definitive representatives of the Albertosaurinae that have been described so far - although there may be other, as yet undescribed genera. All other tyrannosaurids are classified in the second subfamily, the Tyrannosaurinae. Compared to the tyrannosaurines, albertosaurines are characterized by a slimmer body with proportionally smaller, flatter skulls and longer lower leg and foot bones.

The clear similarities between Gorgosaurus libratus and Albertosaurus sarcophagus led many experts to suggest combining both genera - so Gorgosaurus was sometimes recognized as a juvenile synonym of Albertosaurus . Albertosaurus was named before Gorgosaurus and would therefore be the valid name if it was one and the same genus. The paleontologists William Diller Matthew and Barnum Brown questioned the distinction between the two genera in 1922. Gorgosaurus libratus was formally reassigned to Albertosaurus (as Albertosaurus libratus ) by Dale Russell (1970) , and many authors followed this assumption. If Gorgosaurus were indeed a subspecies of Albertosaurus , that would greatly expand the geographical and chronological distribution of the latter. Other experts distinguish between the two genera. The Canadian paleontologist Philip J. Currie notes that there are as many anatomical differences between Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus as there are between Daspletosaurus and Tyrannosaurus , which are almost always listed as separate genera. He also notes that as yet undescribed tyrannosaurids from Alaska , New Mexico and other localities in North America could help clarify the situation.

Discovery history and naming

Gorgosaurus libratus was first described by Lawrence Lambe in 1914. The name is derived from the Greek words γοργός gorgos ("impetuous", "terrible") and σαῦρος sauros ("lizard"). The Artepitheth libratus is the participle of the Latin verb librare , which means "to balance".

The holotype of Gorgosaurus libratus ( NMC 2120) is a nearly complete, skull-attached skeleton discovered by Charles Sternberg in 1913. This skeleton was the first finding of a tyrannosaurid in which the hand has been completely preserved. The find was made in Alberta's Dinosaur Park Formation and is now in the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa . Collectors at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City have discovered hundreds of spectacular dinosaur finds along Alberta's Red Deer River at the same time, including four complete skulls of Gorgosaurus libratus , three of which were associated with skeletons. Matthew and Brown described four of these finds in 1923.

Furthermore, Matthew and Brown described a fifth skeleton ( AMNH 5664) that Sternberg collected in 1917 and then sold to the American Museum of Natural History. It was similar to other Gorgosaurus skeletons, but had a flatter, lighter skull and longer leg proportions. Also, many of the seams between the bones were not fused. Although Matthew and Brown noticed that these features are characteristic of juvenile animals, they nevertheless used this skeleton to describe the new species Gorgosaurus sternbergi . Today's palaeontologists see this skeleton as a juvenile specimen of Gorgosaurus libratus . Dozens of other finds were unearthed from the Dinosaur Park formation and are now on display in various museums across the United States and Canada. Gorgosaurus libratus is thus the tyrannosaurid that appears most frequently in the fossil record. The finds cover almost all ages.

In 1856 Joseph Leidy described two tyrannosaurid teeth of the intermaxillary bone (premaxillary) from Montana. Although there was no evidence of the animal's appearance, the teeth were large and sturdy, so Leidy named them Deinodon . Matthew and Brown wrote in 1922 that these teeth are indistinguishable from those of Gorgosaurus - but in the absence of additional skeletal material, the researchers avoided classifying Deinodon as a synonym for Gorgosaurus . Although the Deinodon teeth look very similar to the teeth of Gorgosaurus , the shape of the tyrannosaurid teeth is very uniform, which is why it is not possible to say with certainty which genus they belonged to. Today Deinodon is considered a noun dubium (dubious name). Various other tyrannosaurid skeletons from the Judith River Formation of Montana may have belonged to Gorgosaurus , although it is unclear whether these finds belonged to Gorgosaurus libratus or a new species. A specimen from Montana ( TCMI 2001.89.1) on display at the Children's Museum of Indianapolis shows serious injuries and illnesses: Healed leg, rib and vertebral fractures were discovered. The animal was also found to suffer from osteomyelitis , an infectious inflammation of the bone marrow that caused permanent tooth loss in the lower jaw. A possible brain tumor was also present.

Reassigned species

Various species were incorrectly ascribed to the Gorgosaurus in the 20th century . A complete skull of a small tyrannosaurid ( CMNH 7541), which Charles Whitney Gilmore described as Gorgosaurus lancensis in 1946, comes from younger rock layers (late Maastrichtian ) of the Hell Creek Formation from Montana . This species was renamed Nanotyrannus in 1988 by Bob Bakker and others . Most paleontologists today believe that Nanotyrannus is a juvenile specimen of the Tyrannosaurus rex . Evgeny Maleev described two small tyrannosaurid skeletons ( PIN 553-1 and PIN 552-2) from the Nemegt formation in Mongolia as Gorgosaurus lancinator and Gorgosaurus novojilovi in 1955 . Although Kenneth Carpenter renamed the smaller skeleton Maleevosaurus novojilovi in 1992 , both skeletons are now considered juvenile specimens of Tarbosaurus bataar .

Paleobiology

Coexistence with Daspletosaurus

In the Dinosaur Park formation, Gorgosaurus lived together with Daspletosaurus , a rarer genus of tyrannosaurins. This is one of the few examples of two tyrannosaurids coexisting. In modern predator guilds, similarly sized predators occupy various ecological niches that limit competition. To what extent this was the case with the tyrannosaurs of the Dinosaur Park Formation is not sufficiently clear. In 1970, Dale Russell suggested that the more common Gorgosaurus might have hunted the nimble hadrosaurs , while the heavier-built Daspletosaurus might have preferred the rarer and more difficult-to-hunt ceratopsians and ankylosaurs . In any case, the digested remains of a juvenile hadrosaur in the abdominal cavity have been preserved in a Daspletosaurus skeleton ( OTM 200) from the Two Medicine Formation from Montana, which was deposited at the same time.

Unlike some other groups of dinosaurs, neither Gorgosaurus nor Daspletosaurus was more common than the other at certain altitudes. Even so, Gorgosaurus appears to be more common in the more northerly formations such as the Dinosaur Park Formation, while Daspletosaurus is more common in the south. The same pattern can be seen in other groups of dinosaurs; for example, chasmosaurine ceratopsians and hadrosaurine hadrosaurs are more common in the Two Medicine Formation of Montana and in southwestern North America during the Campanium, while the Centrosaurinae and Lambeosaurinae dominated the more northern latitudes. Based on this pattern, Holtz suspects that hadrosaurines, chasmosaurines and tyrannosaurines prefer similar habitats. At the end of the late Maastrichtian, tyrannosaurines like Tyrannosaurus rex , hadrosaurines like Edmontosaurus and chasmosaurines like Triceratops were widespread in western North America, while albertosaurines and centrosaurines became extinct and lambeosaurines became very rare.

Ontogeny and Population Biology

Researchers working with Gregory Erickson used bone histology to calculate how old the animals were when they died in various tyrannosaurid finds. This allows conclusions to be drawn about the individual development ( ontogenesis ). Like all tyrannosaurids, Gorgosaurus also showed a very rapid growth lasting about four years, which occurred after a very long juvenile phase. During this growth phase , Gorgosaurus reached a maximum growth rate of 110 kilograms per year. This is slower than with tyrannosaurines like Daspletosaurus and Tyrannosaurus , but comparable to Albertosaurus . Tyrannosaurids shared their habitat only with theropods, which were significantly smaller; However, there are no predators that were between tyrannosaurids and small theropods in size. Since Gorgosaurus and other tyrannosaurids spent about half of their lives in the juvenile stage, some researchers suspect that this niche was occupied by juvenile tyrannosaurids.

Paleoecology

All known skeletons of Gorgosaurus libratus come from the Dinosaur Park Formation, which is famous for its immense density of dinosaur fossils and was deposited around 76 to 72 million years ago. At that time, North America was divided in half by an arm of the sea, the Western Interior Seaway, while in the west the Rocky Mountains began to rise in the course of the Laramian orogeny . Large rivers poured from the rising Rocky Mountains into the Western Interior Seaway to the east, depositing sediments in flood plains along the coast that, among other things, form today's Dinosaur Park Formation. The climate was subtropical and had periodic dry seasons, which led to mass extinctions among large herds of dinosaurs , as can be seen from the numerous bonebeds of the Dinosaur Park formation. The vegetation was formed by conifers , ferns , tree ferns and bedecksamen . The dinosaur fauna consisted of large herds of ceratposi and hadrosaurids; other herbivores were ornithomimosaurs , therizinosaurs , pachycephalosaurs , small ornithopods and ankylosaurs . Small carnivores such as oviraptorosaurs , troodontids, and dromeosaurids hunted smaller prey than the large tyrannosaurids such as Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus .

Individual evidence

- ^ Gregory S. Paul : The Princeton Field Guide To Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9 , p. 105, online ( memento of the original of July 13, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Dale A. Russell : Tyrannosaurs from the late cretaceous of Western Canada (= Publications in Palaeontology. Vol. 1, ISSN 0068-8029 ). National Museum of Natural Sciences (Canada), Ottawa 1970, digitized .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Thomas R. Holtz : Tyrannosauroidea. In: David B. Weishampel , Peter Dodson , Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 111-136.

- ^ Frank Seebacher: A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 21, No. 1, 2001, ISSN 0272-4634 , pp. 51-60, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2001) 021 [0051: ANMTCA] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Philip J. Currie : Cranial anatomy of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada . In: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Vol. 48, No. 2, 2003, ISSN 0567-7920 , pp. 191-226, (PDF; 1.8 MB).

- ↑ a b c Philip J. Currie, Jørn H. Hurum, Karol Sabath: Skull structure and evolution in tyrannosaurid dinosaurs . In: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Vol. 48, No. 2, 2003, pp. 227-234, (PDF; 137 kB).

- ^ A b c William D. Matthew , Barnum Brown : Preliminary notices of skeletons and skulls of Deinodontidæ from the Cretaceous of Alberta . In: American Museum Novitates. No. 89, 1923, pp. 1-9, (PDF; 4.2 MB).

- ^ Philip J. Currie: Allometric growth in tyrannosaurids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia. In: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. Vol. 40, No. 4, 2003, ISSN 0008-4077 , pp. 651-665, doi : 10.1139 / e02-083 .

- ^ A b William D. Matthew, Barnum Brown: The family Deinodontidae, with notice of a new genus from the Cretaceous of Alberta . In: Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 46, No. 6, 1922, ISSN 0003-0090 , pp. 367-385, (PDF; 1.8 MB).

- ↑ Thomas D. Carr, Thomas E. Williamson, David R. Schwimmer: A new genus and species of tyrannosauroid from the Late Cretaceous (middle Campanian) Demopolis Formation of Alabama. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 25, No. 1, 2005, pp. 119-143, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2005) 025 [0119: ANGASO] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ^ Gregory S. Paul: Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster, New York NY et al. 1988, ISBN 0-671-61946-2 .

- ↑ a b Lawrence M. Lambe : On the fore-limb of a carnivorous dinosaur from the Belly River Formation of Alberta, and a new genus of Ceratopsia from the same horizon, with remarks on the integument of some Cretaceous herbivorous dinosaurs. In: Ottawa Naturalist. Vol. 27, No. 10, 1914, pp. 129-135, digitized .

- ↑ a b Lawrence M. Lambe: On a new genus and species of carnivorous dinosaur from the Belly River Formation of Alberta, with a description of Stephanosaurus marginatus from the same horizon. In: Ottawa Naturalist. Vol. 28, No. 1, 1914, pp. 13-20, digitized .

- ^ Henry George Liddell , Robert Scott : A Lexicon abridged from Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon. 24th edition, carefully revised throughout. Ginn, Boston 1891 (Reprinted edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5 ).

- ↑ a b c d Thomas D. Carr: Craniofacial ontogeny in Tyrannosauridae (Dinosauria, Coelurosauria). In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 19, No. 3, 1999, pp. 497-520, doi : 10.1080 / 02724634.1999.10011161 .

- ↑ Joseph Leidy : Notice of remains of extinct reptiles and fishes, discovered by Dr. FV Hayden in the badlands of the Judith River, Nebraska Territory. In: Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Vol. 8, 1956, ISSN 0097-3157 , pp. 72-73, digitized .

- ↑ John Pickrell: First dinosaur brain tumor found, experts suggest. In: National Geographic News. November 24, 2003, accessed July 24, 2014 .

- ↑ Meet the Gorgosaur. In: The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014 ; Retrieved July 24, 2014 .

- ^ Charles W. Gilmore : A new carnivorous dinosaur from the Lance Formation of Montana (= Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. Vol. 106, No. 13, ISSN 0096-8749 = Smithsonian Institution. Publication. 3857). Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 1946, digitized .

- ^ Robert T. Bakker , Michael Williams, Philip J. Currie: Nanotyrannus, a new genus of pygmy tyrannosaur, from the latest Cretaceous of Montana. In: Hunteria. Vol. 1, No. 5, 1988, ZDB -ID 1251702-1 , pp. 1-30.

- ↑ Евгений А. Малеев: Новый хищный динозавр из верхнего мела Монголии. In: Доклады Академии наук СССР. Vol. 104, No. 5, 1955, ISSN 0002-3264 , pp. 779-783 (In English: New carnivorous dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. Online (PDF; 12.41 kB) ).

- ↑ Ken Carpenter : Tyrannosaurids (Dinosauria) of Asia and North America. In: Niall J. Mateer, Chen Pei-ji (Eds.): Aspects of Nonmarine Cretaceous Geology. China Ocean Press, Beijing 1992, ISBN 7-5027-1463-4 , pp. 250-268.

- ↑ Анатолий К. Рождественский: Возрастная изменчивость и некоторые вопросы систематики динозавров Азии. In: Палеонтологический Журнал. No. 3, 1965, ISSN 0031-031X , pp. 95-109.

- ↑ a b James O. Farlow, Eric R. Pianka: Body size overlap, habitat partitioning and living space requirements of terrestrial vertebrate predators: implications for the paleoecology of large theropod dinosaurs. In: Historical Biology. Vol. 16, No. 1, 2002, ISSN 0891-2963 , pp. 21-40, doi : 10.1080 / 0891296031000154687 (currently unavailable) .

- ↑ David J. Varricchio: Gut contents from a Cretaceous tyrannosaurid: implications for theropod dinosaur digestive tracts. In: Journal of Paleontology. Vol. 75, No. 2, 2001, ISSN 0022-3360 , pp. 401-406, doi : 10.1666 / 0022-3360 (2001) 075 <0401: GCFACT> 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ Gregory M. Erickson, Peter J. Makovicky , Philip J. Currie, Mark A. Norell , Scott A. Yerby, Christopher A. Brochu: Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs. In: Nature . Vol. 430, No. 7001, 2004, pp. 772-775, doi : 10.1038 / nature02699 .

- ↑ David A. Eberth, Anthony P. Hamblin: Tectonic, stratigraphic, and sedimentologic significance of a regional discontinuity in the upper Judith River Group (Belly River wedge) of southern Alberta, Saskatchewan, and northern Montana. In: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. Vol. 30, No. 1, 1993, pp. 174-200, doi : 10.1139 / e93-016 .

- ↑ Joseph M. English, Stephen T. Johnston: The Laramide Orogeny: what were the driving forces? In: International Geology Review. Vol. 46, No. 9, 2004, ISSN 0020-6814 , pp. 833-838, doi : 10.2747 / 0020-6814.46.9.833 .

- ^ David A. Eberth: Judith River Wedge. In: Philip J. Currie, Kevin Padian (Eds.): Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press, San Diego CA et al. 1997, ISBN 0-12-226810-5 , pp. 199-204.

- ^ Dennis R. Braman, Eva B. Koppelhus: Campanian palynomorphs. In: Phillip J. Currie, Eva B. Koppelhus (eds.): Dinosaur Provincial Park. A Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 2005, ISBN 0-253-34595-2 , 101-130.

- ↑ James O. Farlow: Speculations about the diet and foraging behavior of large carnivorous dinosaurs. In: American Midland Naturalist. Vol. 95, No. 1, 1976, ISSN 0003-0031 , pp. 186-191, doi : 10.2307 / 2424244 .

Web links

- Gorgosaurus on Palaeos.com (English)