Servant songs

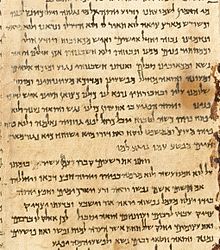

Four related texts in the biblical book Isaiah are referred to as God's servant songs .

Bernhard Duhm's commentary on Isaiah (1892)

Bernhard Duhm was the first to point out the peculiarity of these texts, which he called Ebed Jahve songs in his Isaiah commentary (1892) (Hebrew ebed עבד means servant): “Disciples (as Deutero-Isaiah ) and at least post-exilic are the Ebed Jahve songs c .42 1-4 ; c.49 1-6 ; c.50 4-9 ; c.52 13 - 53 12 , which are based on Deutero-Isaiah as well as on Jeremiah and the Book of Job, but in turn on Dtjes. are not known, because otherwise he would have had to take them into consideration. ”Duhm had already made a corresponding assumption in 1875: he called the four God's servant songs“ Pericopes, ... which externally differ so sharply against the rest of the text in terms of style and language stand out that one cannot immediately dismiss the assumption that they ... were probably borrowed from elsewhere. "

The term servant songs is widely used in exegetical literature, although strictly speaking they are not songs .

Context of the Book of Isaiah

Many exegetes in the succession of Duhm assume that the servant songs formed a coherent, independently handed down text, which was editorially incorporated into the text of Deutero-Isaiah. According to Duhm, the series of songs for the servant of God had nothing to do with the heterogeneous Deutero-Isaiah text surrounding it. Gerhard von Rad took on a mediating position : the songs came from Deutero-Isaiah, but "with all the connectedness, they are also somewhat isolated in the preaching of this prophet and are also shadowed by special riddles." In the meantime, research has established a variety of references to the exist between the book of Isaiah and the songs of the servants of God. "The isolation of the servants' songs as scattered texts that show no connection at all with the context must be viewed in retrospect as a research mistake."

Menahem Haran preferred the phrase “Servant Poetic Texture” to show that Jacob / Israel is particularly often addressed as “my (ie YHWH's) servant” in chapters Isa 40 to 48. YHWH created Jacob, chosen from the womb for a specific task: to establish justice in the world. Haran characterized the servant's mission as a combination of a universalistic message of justice and a message of national liberation. So Haran developed an image of the servant from the final text of chapters 40 to 48. The God's servant song is a place of particular poetic condensation within this chapter.

Content of the songs

First song

These verses are about God's speech. YHWH introduces his servant, who has a prophetic and royal task for the world of nations.

This song is shaped by the world of courtly ceremonies; a heavenly court can be imagined as a forum. The following songs for the servants of God leave this environment, they stand in prophetic tradition; however, the fourth servant song will tie in with the royal tradition in a different way. The reader is reminded of the designation of a king (1 Sam 9: 15–17), which, in contrast to the calling of a prophet, requires publicity and acclamation.

Second song

The servant presents himself to the world of nations. He looks back on his election by YHWH and sums up (verse 4) that he has so far tried “in vain, for nothing”. Thereupon he reports of a new speech of God that came to him: if he should lead Israel back to YHWH so far, his task is now extended to the whole world of peoples, he is “the light of the peoples”.

Third song

The servant describes the special gifts with which YHWH equipped him for his task: he can talk to the tired and listen like a disciple. He reports on the abuse he has suffered in the performance of his mission and emphasizes his trust in YHWH to help him.

As with the second song of the Servant of God, this text is particularly close to the so-called denominations of Jeremiah. These texts, for example Jer 15,16–17 LUT , are not a prophetic message to fellow men, but Jeremiah's conversations with himself and with God.

Fourth song

Isa 52,13 LUT to Isa 53,12 LUT

In this text, a group speaks, framed by a speech from God (52: 13-15 and 53: 11b-12). She looks back on the life of the servant who was mistreated and is now dead and buried, for which the speaking group blames themselves. Verses 10–11a describe YHWH's devotion to the servant who thereby has a future (future tense in verse 11a). The framing speech of God contains the rehabilitation and exaltation of the servant.

Possibilities of interpretation

The servant songs ask the reader who this servant is; the discussion about this already begins in the biblical book of Isaiah (for example: Isa 61,1–3 LUT ).

Collective interpretation

The servant of God is

- empirical Israel;

- the “better” part of Israel (specifically: the community that has returned from exile in Babylon);

- the future or ideal Israel.

Individual interpretation

The servant of God is

- a king (specifically: Cyrus);

- a figure like Moses , who gives direction and intervenes as a prayer for Israel;

- a prophetic figure like the prophet Jeremiah .

None of these six types of interpretation can, taken by themselves, fully explain the servant songs; this mystery was probably intentional.

The collective interpretation can be based on the address "Israel" in Isa 49.3, but has the difficulty that the servant, according to Isa 49.6, has a task for Israel, i.e. cannot be identical with Israel.

The widespread autobiographical interpretation, which sees in the prophet Deutero-Isaiah himself, ascribes the fourth servant song to a group of students of the prophet, to whom the divine speech was also given. The difficulty here is that the first three songs are aimed at the fourth song and form a compositional unit with it.

Christian reception

The interpretation of the life path of Jesus of Nazareth was formulated by the early church with the help of the servant songs, especially the fourth song; they are therefore texts that are very important for Christians. This is shown by the series of statements about Christ in the Apostles' Creed : born - suffered - died - buried.

The great Christian interest in the servant songs can be reflected in the translation. For example, in the first song it is said that the servant of God brings the peoples mischpat ִ (ִִמשפט), “legal decision”. With others, Gerhard von Rad would like to translate this term here with "truth", "one could almost say: the right religion."

Servant songs as sermon texts

(Evangelical pericope order )

- First Sunday after Epiphany (VI)

- 17th Sunday after Trinity (IV)

- Palm Sunday (IV)

- Good Friday (VI)

Servant songs in church music

- Jochen Klepper : He wakes me up every morning (EG 452)

- Melchior Franck : The comforting 53rd chapter from the prophet Isaiah

Web links

- Hans-Jürgen Hermisson : Art. Gottesknecht ( WiBiLex )

literature

- Bernhard Duhm : The book of Isaiah translated and explained (hand commentary on the Old Testament). Göttingen 2nd edition 1902.

- Karl Budde : The so-called Ebed Yahweh songs and the meaning of the servant of Yahweh in Isa 40-55. A minority vote . Casting 1900.

- Claus Westermann : The book of Isaiah. Cape. 40-66 (ATD 19), Göttingen 1966.

- Herbert Haag : The servant of God at Deutero-Isaiah (results of research 233), Darmstadt 1985.

- Gerhard von Rad : Theology of the Old Testament Volume 2: The theology of the prophetic traditions of Israel , Munich 9th ed. 1987, pp. 260–270.

- Bernd Janowski , Peter Stuhlmacher (Ed.): The suffering servant of God. Jes 53 and its history of effects (FAT 14), Tübingen 1996.

Individual evidence

- ^ Claus Westermann: ATD . 1966, p. 11 .

- ^ Bernhard Duhm: The book of Isaiah . 1902, p. xiii .

- ↑ Bernhard Duhm: The theology of the prophets as a basis for the inner history of the development of the Israelite religion . Bonn 1875, p. 288-289 .

- ^ Claus Westermann: ATD . 1966, p. 77 .

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: Introduction to the Old Testament . 4th edition. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1989, p. 265 .

- ^ A b Gerhard von Rad: Theology of the Old Testament . tape 2 , 1987, pp. 261 .

- ^ Ulrich Berges, Willem AM Beuken: The book Isaiah: An introduction . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016, p. 140 .

- ↑ Menachem Haran: The literary structure and chronological framework of the Prophecies in Is xl-xlviii . In: Vetus Testamentum, Supplements . tape 9 . Brill, Leiden 1963, p. 127-155 .

- ↑ Werner H. Schmidt: Introduction to the Old Testament . 1989, p. 265-266 .

- ^ Claus Westermann: ATD . 1966, p. 78 .

- ^ Gerhard von Rad: Theology of the Old Testament . tape 2 , 1987, pp. 209 .

- ^ Claus Westermann: ATD . 1966, p. 78 : "... the concealing speech is intentional and we do not even know whether the hearers of the words at that time should not also have hidden a lot about them."

- ^ Claus Westermann: ATD . 1966, p. 208 .

- ^ Claus Westermann: ATD . 1966, p. 79-80 .