Heidelberg old town

|

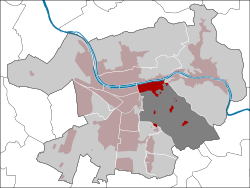

Altstadt district of Heidelberg |

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 49 ° 24 '39 " N , 8 ° 42' 23" E |

| surface | 13.78 km² |

| Residents | 10,194 (2012) |

| Population density | 740 inhabitants / km² |

| District number | 002 |

| structure | |

| Townships |

|

| Source: City of Heidelberg (PDF; 128 kB) | |

The old town of Heidelberg forms a district on the southern bank of the Neckar . It extends between the river and the slope of the Königstuhl below the Heidelberg Castle . Established according to plan in the 13th century and expanded at the end of the 14th century, today's old town remained synonymous with the city of Heidelberg well into the 19th century. The old town owes its face as a baroque town on a medieval floor plan to the reconstruction of Heidelberg after its destruction in 1693 in the Palatinate War of Succession .

geography

Heidelberg's historic old town is located on the left, southern bank of the Neckar shortly before it exits the Odenwald into the Upper Rhine Plain on a narrow wedge of alluvial sand. This valley bottom, which contracts in a triangular shape towards the east, is 1900 meters long and an average of 450 meters wide. In the south it is bordered by the steeply rising Königstuhl with its secondary peak, the Gaisberg . On the opposite northern bank of the Neckar, the Heiligenberg rises directly on the Neuenheimer side .

Structure of the old town as a district

The Altstadt district not only includes the historical areas of the medieval city's founding, but also extends far to the south over a substantial part of the Königgstuhl area. As a district, the old town borders on Schlierbach , Neuenheim on the other bank of the Neckar , on Bergheim , the West and the Südstadt , on Rohrbach and the Boxberg , and with Gaiberg , Bammental and the Neckargemünder district of Waldhilsbach on three municipalities of the Rhine-Neckar- Circle . For statistical purposes it is subdivided into three districts; the following data are as of 2012.

The Kernaltstadt district (105.7 hectares, 5146 inhabitants) comprises the oldest part of the city between Universitätsplatz and Plankengasse. The economy is dominated by the catering trade , especially along the Hauptstrasse and Untere Strasse as well as in the area between Heiliggeistkirche and Alter Brücke . The relatively small Obere, Ostliche or Jakobsvorstadt, located between Plankengasse and Karlstor , from the 14th century, also belongs to the district . The eponymous Jakobsstift, first mentioned in 1387, was destroyed in the town fire in 1693. A new building that was built as a Carmelite Church between 1702 and 1713 was demolished in the period after 1805. Part of the district are also the area of the Heidelberg Castle , the Schlossberg, which was legally independent from the city until 1743, and the area along the uphill Klingenteichstraße including the Molkenkur . On the western edge of the old town, in the transition area to the suburb , there are important central facilities of the university, including two canteens .

The Voraltstadt , also called Lower or Western suburbs, ranging from University Square west to the Bismarckplatz , where it borders the district Bergheim. Created in 1392 for the purpose of resettling the population of the subsequently deserted medieval village of Bergheim, it proved to be oversized for a long time. Larger parts off the main axis remained open spaces until the beginning of the 19th century; there was only continuous development along the Plöck from 1800 onwards. The economic focus, especially along the main street, is in the retail sector. The area of the district is 69.6 hectares, the population is 4916.

The structure of the third district, Königstuhl , differs greatly from the other two. With 1202.6 hectares it covers 87% of the area of the district, but with 132 only 0.13% of the population. It extends over the summit and large parts of the flanks of the eponymous local mountain of the city as well as its foothill Gaisberg and is largely forested, with a few clearing islands as sprinkles. Only 2.9% of the area is built on. The resident population is mainly at home on the Kohlhof , a coherent development can also be found around the summit plateau of the Königstuhl. Also in the area of the district are the Ehrenfriedhof and the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics as well as the Speyerer Hof. Named after a former mayor of the city, it was originally an estate with management. The city sanatorium for medium- sized businesses was built in its place in 1927 ; today the hospital belongs to the Schmieder Clinic Group .

Streets and squares

Road network

The city plan of the old town depends on the topographical conditions. According to the orientation of the river and the mountainside, three streets lead through the old town: Neckarstaden and Am Hackteufel ( B 37 ) on the banks of the Neckar, the central main street and the Friedrich-Ebert-Anlage at the foot of the mountain. In addition, there is the Plöck in the western area of the old town between Hauptstraße and Friedrich-Ebert-Anlage. These streets, running in a west-east direction, are connected by a system of cross streets (which, with seven exceptions, are called “alleys”). The road network shows a morphological difference between the older core old town with its numerous alleys and the less differentiated old suburb.

Places

The following important places are located in Heidelberg's old town from west to east:

- The Bismarck space is situated close Sofienstraße, which marks the western boundary of the town, and forms the link between the old and Bergheim. The main street starts at the edge of Bismarckplatz. The square, which is served by numerous bus and tram lines, is one of the most important transport hubs in Heidelberg along with Willy-Brandt-Platz , which is located at the main train station , and plays a major role in the development of the old town by local public transport.

- The Friedrich-Ebert-Platz is located on the southern edge of the old town at the Friedrich-Ebert-Anlage. The space previously used as a parking lot was redesigned between 2008 and 2010 when an underground car park was built under the space. The listed neoclassical colonnade from 1927 on the north side of the square was demolished. This originally had the function of a market hall, but was recently cordoned off because of its poor state of construction.

- The University Square is the central square of the old town. It extends at an angle to the west and south of the Old University . In the north it is affected by the main street, on its southern edge is the New University . The Grabengasse on its western edge runs in place of the old city fortifications and marks the border between the old town and the suburb. The Augustinian monastery , where Martin Luther appeared in the Heidelberg disputation in 1518, was originally located on the site of the Universitätsplatz . After its destruction in the Palatinate War of Succession, the monastery was not rebuilt; instead, Paradeplatz was built in its place in 1705, later renamed Ludwigsplatz and today is called Universitätsplatz.

- The market square is located at the Heiliggeistkirche in the center of the old town and was already part of the oldest city plan in Heidelberg. The main street runs past on its south side. In the east of the market square is the town hall , in the west the square is dominated by the Church of the Holy Spirit . In the middle of the square is the Hercules Fountain , which was built between 1703 and 1706 and is intended to commemorate the enormous efforts of rebuilding the city. The part of the square north of the Heiliggeistkirche is called the fish market.

- The Kornmarkt is a small square not far from the market square on the south side of the main street. It is dominated by the statue of the Madonna designed by the sculptor Pieter van den Branden in its center. The elector Karl III. In 1718 Philip had it set up as a visible sign of the Counter Reformation in the Electoral Palatinate, which had recently become Catholic.

- The Karlsplatz is located south of the main road in the eastern part of the old town. The square, which is unusually large for the small-scale old town, was built in 1807 on the site of a Franciscan monastery that had been demolished four years earlier . The fountain in the center of the square, designed by Michael Schoenholtz in 1978, is reminiscent of the humanist and cosmographer Sebastian Münster (1488–1552), who worked in the Franciscan monastery for several years at the beginning of the 16th century. Karlsplatz is lined by the Academy of Sciences building and the Palais Boisserée .

history

- See also: History of Heidelberg

founding

Heidelberg's old town is the nucleus of the city of Heidelberg. Nevertheless, it is younger than many parts of the city that were later incorporated, which go back to the founding of villages in the Franconian period and have been mentioned in documents since the 8th century. The first mention of Heidelberg can be found in a document from the Schönau monastery from 1196. Even before that, there was a castle in Heidelberg on the slope of the Königstuhl and at its feet a small hamlet in the area around the Peterskirche .

Today's old town goes back to a planned city foundation. For a long time it was assumed that this took place in Worms between 1170 and 1180, but more recent findings suggest that Heidelberg was only founded in the Wittelsbach period around 1220. The newly founded city encompassed the area that is known today as the old city center and was given a rectangular ladder layout, as was typical of the early Gothic period: three streets, Untere Straße , Hauptstraße and Ingrimstraße, ran parallel to the river and became regular with cross streets Split blocks. At the intersection of the main axes in the middle of the city was the market square. From 1235 at the latest, Heidelberg was surrounded by a wall. In the courtyard of the New University and as part of the history seminar, you can still see the witch's tower, which once strengthened the city wall towards the Rhine plain. The mantle or women's tower on the banks of the Neckar is also largely preserved, but built into the hay barn. City gates were located at both ends of the main street and on Steingasse on the Neckar. A bridge over the Neckar is first mentioned in 1284. Although it was to remain the main church of Heidelberg for a long time, the Peterskirche and the surrounding old castle hamlet, later called Bergstadt, were outside the city limits until the 18th century.

City expansion and subsequent development

In 1392 the urban area of Heidelberg was expanded to include the suburbs. The western city limits were extended to the height of today's Bismarckplatz, thus doubling the area of Heidelberg. Reasons for the city expansion were, on the one hand, the increased demand for living space after the university had been founded six years earlier , and on the other hand, conflicts between the residents of Heidelberg, who had fields and vineyards in the districts of Bergheim and Neuenheim , with the inhabitants of these villages. Therefore, the district of Bergheim was incorporated into the city of Heidelberg, the residents of the village were forcibly relocated to the newly created suburb. The urban area had now been given an expansion that corresponds to today's old town and was to last into the 19th century. The area of the suburbs remained very loosely developed for a long time. On the outskirts of the city in the area of today's Sophienstrasse, a new western wall with the Speyerer Tor was built.

The growing importance of Heidelberg as the royal seat of the Electoral Palatinate had an impact on building activity. Elector Ruprecht III. , who was the first and only Elector of the Palatinate to be elected Roman-German King, had the chapel on the market square expanded into a representative Church of the Holy Spirit in 1400 . The electoral stables and armory on the banks of the Neckar were built in the 16th century. At that time there was an Augustinian , a Franciscan and a Dominican monastery in the area of today's old town . In addition, the monasteries Lorsch , Schönau , Sinsheim and Maulbronn as well as the dioceses of Worms and Speyer maintained courtyards in Heidelberg. Only the Wormser Hof has survived to this day.

Although the ground plan of the city has remained almost unchanged and most of the striking large buildings have been preserved, albeit in a modified form, the cityscape of late medieval and early modern Heidelberg differed considerably from today's: most of the buildings were half-timbered houses with the gable side of the street turned to.

Destruction and rebuilding

The destruction of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) was still limited in Heidelberg. But the War of the Palatinate Succession (1688–1697) was extremely momentous for the city . Heidelberg was captured by French troops twice, in 1688 and 1693 , and completely devastated. Only a few buildings such as the churches, the armory or the House of the Knights survived the destruction.

While Heidelberg Castle has remained in ruins since the War of the Palatinate Succession, after the end of the war work began to rebuild the old town. The old floor plan was retained and new baroque-style houses were built on the foundations of the destroyed buildings . To this day, the city has retained this face as a baroque city on a medieval floor plan. The stone-built baroque town houses are particularly valuable as an ensemble, as only a few houses such as the Palais Morass (1716) or the Haus zum Riesen (1707) are of art historical importance. Johann Adam Breunig and Johann Jakob Rischer deserve a mention as architects who played a key role in the reconstruction of Heidelberg . The greatest urban development achievements of the reconstruction period include the construction of Paradeplatz (1705; today Universitätsplatz) in place of the old Augustinian monastery and the construction of the Jesuit quarter with the Jesuit church (1712–1723) and the Jesuit college (1703–1734) as well as other public buildings such as the town hall (1701–1703), the Old University (1712–1735) or the Seminarium Carolinum (1750–1753).

19th and 20th centuries

In the course of the 19th century, the development in the previously sparsely developed suburb was densified. During the founding period , the university library (1901–1905) in Plöck and the town hall (1901–1903) on Neckarstaden, two important public buildings that combine historicism with influences from Art Nouveau .

The construction of the university library is related to the inner-city expansion of the university, which is confronted with increased space requirements due to the increasing number of students. Even today, the old town is still one of the most popular residential areas for students at Heidelberg universities. Even before the inner-city expansion, the Alte Anatomie (1847–1849) and the Friedrichsbau (1861–1864) were used as scientific institute buildings. The New University (1931–1934), financed by American donations, is the most visible intervention of university building activity in the cityscape .

Heidelberg was largely spared the destruction of the Second World War . The historic building fabric of the old town survived the war unscathed. Only the Old Bridge , like the other bridges over the Neckar, was blown up by Wehrmacht troops when they withdrew in 1945 . Thanks to a fundraising campaign, the rebuilt Old Bridge was inaugurated again in 1947. After individual university facilities had already been relocated to the other side of the Neckar after the war, the construction of a completely new campus in Neuenheimer Feld began in 1951 . Nevertheless, new university buildings were also built in the old town in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1970s, then Lord Mayor Reinhold Zundel began an extensive renovation of the old town , which was highly controversial at the time. Numerous historic buildings were demolished; others were renovated and opened to a more affluent public. Tram and car traffic were banned from the main street in 1976, making it one of the longest pedestrian zones in Europe.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Oliver Fink: Little Heidelberg City History , Regensburg 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Arnold Scheuerbrandt: The rise and fall of Heidelberg in the time of the Electorate of the Palatinate , in: Elmar Mittler (Hrsg.): Heidelberg. History and Shape , Heidelberg 1996, here p. 50.

- ↑ Fink, p. 22 f.

- ↑ Fink, p. 24

- ↑ Scheuerbrandt, p. 55.

- ^ Peter Anselm Riedl: Heidelberg's old town. Shape, profane buildings, problems relating to monument preservation , in: Elmar Mittler (Hrsg.): Heidelberg. History and Shape , Heidelberg 1996, here p. 108.

- ^ Heidelberg24 - district ranking. Retrieved October 6, 2016 .

literature

- Peter Anselm Riedl: Heidelberg's old town. Shape, profane buildings, problems relating to monument preservation. In: Elmar Mittler (Ed.): Heidelberg. History and shape . Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 1996. pp. 106–129. ISBN 3-9215-2446-6

- State Office for Monument Preservation (publisher): Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany, cultural monuments in Baden-Württemberg, city district of Heidelberg , Thorbecke-Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-7995-0426-3

- Medieval city floor plans. With an epithet by Arnold Scheuerbrandt. Historical Atlas of Baden-Württemberg , ed. from the Commission for Historical Regional Studies in Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart 1972–1988, Map IV, 6

- Adolf von Oechelhäuser , Franz Xaver Kraus (ed.): The art monuments of the Grand Duchy of Baden , (Volume 8.2): The art monuments of the Heidelberg district (Heidelberg district), Tübingen 1913, p. 66ff. Available online at Heidelberg University Library, right to the beginning of the section

- Old town at a glance 2012 . Statistical data on the Altstadt district on the website of the city of Heidelberg, PDF, 149 kB

Web links

- The Altstadt district on the site of the city of Heidelberg