Düna manor

A former stone building on the archaeological site of a deserted settlement on the outskirts of Düna in the district of Osterode am Harz is referred to as the manor house in Düna . The Heritage Institute in Hanover led to the settlement only to interdisciplinary guided Prospektionsmaßnahmen from 1981 to 1985. Excavations by. Accordingly, the settlement was built on several streams of the Daugava River during the Roman Empire from wooden buildings, the residents of which smelted ore from the Harz . In the 10th century a representative stone building was erected, which is interpreted as a mansion due to its massive construction . The 3.5 meter thick sediments of the filled stream bed made it possible to date the excavation complex. Accordingly, the settlement existed from 3rd / 4th. Century with interruptions until the 13th / 14th. Century in a period of about 1000 years.

The findings of the excavation were sensational in that the ores found in the Harz, especially non-ferrous metal ores from the Rammelsberg , but also silver-bearing lead ores from the Upper Harz , could be dated to the 3rd century. Until then, it was assumed that mining on the Rammelsberg did not start until 968, according to written records, and that mining in Upper Harz started much later.

location

The former settlement area with the manor Düna was on a plateau of 260 to 270 m above sea level. NN under the protection of a hill further north. A few hundred meters to the west is the gypsum karst landscape of Hainholz as a striking karst area with sinkholes , streams and caves . The settlement was in a favorable, south-exposed location on a gently sloping southern slope. It was located between two arms of the current Daugava stream, which rose as springs just above the buildings of the domain that existed until 1935 . The streams ran diagonally towards each other and converged in the area of the settlement. In it, surface water ran off on the damming clay subsoil. The water flow is likely to have completely decreased in the dry season.

The water diverted to the south and formed a valley below Düna . The Kurhannoversche Landaufnahme from 1785 shows both runs, while the eastern one was leveled later. It is still recognizable today as a depression in the terrain. At the confluence there was a peninsula that was protected by the watercourses. In this sheltered location was a flat hill about 20 meters in diameter, under which the stone building was discovered as a presumed manor during the excavations. The double and triple creek flowed through the settlement during the entire settlement phase. Originally it ran in an erosion channel 3 meters deep and 10 meters wide, which the residents had partially relocated and almost filled in. The site with the remains of the settlement has been used as a meadow for a long time and has not been changed or built over. Today it is located on the outskirts south of the buildings of the former domain. After the excavations, the area was turned into arable land.

Desert history

The first written mention of Düna was in 1286 as Dunede. The settlement is mentioned in a deed of donation from some ministerial officials who bequeathed some Hufen land and bailiwick rights to a chapel in Düna to the Jacobi monastery in Osterode . The location of this chapel is no longer known today, it is believed to be in the manor house of the former domain that was built in the 16th century. Later, Düna is mentioned in documents in 1329, 1336 and 1372, whereby it was designated as Vorwerk Dunde in 1372 . Düna was located on a medieval long-distance trade route in a north-south direction, which led south to an important traffic intersection at the time, on which the Palatinate Pöhlde and the Wallburg Pöhlde were also located. At the end of the 14th century the settlement fell into desolation . Only a few meters north of the first settlement, Düna was rebuilt in the first half of the 16th century as a forework. The agricultural property was leased to senior ducal officials of the Herzberg Castle for a long time and had a brick factory . Only a few people lived on the estate. In the 19th century there were around 30 people. The property became a state domain and when the last tenant died around 1930, the Hannoversche Siedlungsgesellschaft acquired it. In 1935 she divided the property into farms and further buildings were built. Due to the development, the surrounding area with the earlier settlement remains largely untouched and undeveloped.

Settlement phases

On the basis of the archaeological findings, five different main phases of settlement are distinguished, for which sub-phases are again defined for phase I:

- Phase I: timber construction phase from 3rd / 4th to 9th century

- Phase Ia: beginning of settlement before 275 AD

- Phase Ib: Beginning around 750 AD with stream leveling

- Phase Ic: not limited in time, installation of fascines

- Phase II: Stone construction phase from the 10th to the 11th century with the construction of the representative stone building

- Phase III: Conversion of the stone building after fire in the 11th / 12th century

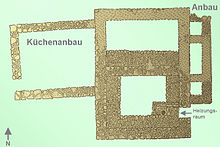

- Phase IV: Extension of the stone building with kitchen extension in the 12th / 13th centuries century

- Phase V: Destruction of the settlement complex in the 13th / 14th centuries century

archeology

Prospecting

In 1979, a resident of Düna reported irregularities in the soil in a meadow south of the buildings of the former domain to the Osterode district . He had also found ceramic parts from the Middle Ages that had come to light through mole activity. On the meadow there was a 1 meter high, horseshoe-shaped hill with a diameter of about 20 meters, which gave the impression of a ring wall . There was also a deep depression in the area, which later turned out to be a stream. In 1979 a geologist carried out an investigation who carried out 19 superficial boreholes to a depth of 3 meters. He came across rubble through bricks , slag , mortar and clay , which raised the suspicion of a desert .

When the meadow area was about to be turned into arable land in 1981, a four-week trial excavation was carried out to clarify whether it was relevant to a monument. The first discoveries already indicated an extraordinary facility. To explore the location, nature and extent of the site, the institute was on Monuments from Hannover extensive interdisciplinary Prospektionsmaßnahmen make as phosphate mapping , geoelectric , ground penetrating radar , aerial archaeological shots and holes . The usual phosphate mapping in desert prospecting was carried out on an area of 550 meters by 300 meters south of the domain building, where the hill-like elevation was and the settlement center was assumed. This is where the highest levels of phosphate were found in the soil, indicating that there was an earlier settlement on an area of 20,000 m².

Excavations

The four-week trial excavation carried out by the Institute for Monument Preservation in 1981 later turned into an exemplary desert excavation, which, through five years of excavation activity, developed into the largest settlement excavation in the Harz region by 1985. In the excavation campaigns from 1981 to 1983, the investigations were limited to the core area of the hill, under which the foundations of a stone building were excavated. The excavations in 1984 and 1985 extended to the area. A total of around 500 m² was excavated, which makes up about 2.5% of the total populated area.

During an excavation cut through the former stream to a depth of 3.5 meters, the sediments were examined intensively. The backfilled stream is still draining the terrain, so that during the excavations, water running down the slope pressed into the excavation area. As a result, the water level on the excavation site had to be lowered by laying a drainage system with pipes and pumps. In the permanently moist areas of the excavation area, there were favorable conservation conditions for organic materials such as posts, fascines, boards and beams.

Stone building

The age of the representative tower-like stone building was determined using found ceramics, with the help of stratigraphically determinable soil horizons and radiocarbon dating of found objects. After that, it was completed in the early 10th century and expanded in the centuries that followed. From the beginning it lay like a peninsula between two ditches. On one side the trench was led past with fascines . An additional trench was dug on another side. Drainages and small channels were created on the building site to prevent water from accumulating on the slopes. The stone building, originally located on the slope of a stream, was 11 meters long and 8 meters wide. It was divided roughly in the middle by an intermediate wall and partly with a cellar. Due to the hillside location, there was a basement room in which there was a 4 m² boiler room for heating the building. The outer walls were 1.1 meters thick and made of broken dolomite stones . On the east side there was a narrow annex , the function of which is not known. A fire in the building on 11/12 Century could be read from mighty layers of charcoal. After that, it was rebuilt on the old foundations, which were significantly reinforced. This created the tower-like character. After the brook had been backfilled and pushed back, a square extension was built on the west side, which the finds (kettle hooks, kettle) identified as a kitchen. It had a stone foundation, while the building structure was made of wood. During this time of reconstruction, a ditch was also built so that the stone building was on a small island. The island property was paved with small pebbles. A thick layer of fire rubble with a thick layer of brick, presumably from the collapsed roof, suggests that the entire building complex was built around the 13th / 14th centuries. Century fell victim to a fire.

Evaluation and consequences

The excavations between 1981 and 1985 revealed the settlement history of a desert from the Roman Empire in the 3rd century to the late Middle Ages in the 13th and 14th centuries. Read the century.

According to this, the settlement was built in the 3rd or 4th century on a slight southern slope, which can be seen from the Roman imported ceramics from this time. The settlement area was characterized by three creek beds cut up to 7 meters deep. There were buildings on the peninsulas created by the confluence. A group of houses at ground level and a pit house , which was probably surrounded by a fence, could be archaeologically proven . There was also a racing furnace for smelting ore. Settlement lasted continuously for centuries, although it must have been at least partially destroyed in the 7th century. Later the stone building was built, which burned down in the 10th or 11th century and was then rebuilt. The end of the settlement came in the 13th or 14th century when it was destroyed again by fire.

The excavations for the first time allowed a glimpse into the earliest iron production from Upper Harz iron ore, copper recovery from ores of the Goslar Rammelsberg and silver recovery from Upper Harz gangue as a mining archeology in the resin has not been used until then. As a result, the archaeological investigations extended to the Harz ore deposits and in 1992 the Mining Archeology Unit was established in Goslar as part of the Institute for Monument Preservation. Since 1998, as part of the successor organization of the Lower Saxony State Office for Monument Preservation , it has been responsible for the preservation of monuments in former mining areas in the Harz Mountains ( district of Goslar and former district of Osterode ).

Found objects

Objects found in connection with buildings were, for example, door keys , door locks and window and door hinges made of metal. In connection with earlier hunting activities, the lower jaw of a bear and the skull of an elk have been found. Arrowheads, hunting knives , stirrups and horseshoes were among the finds as hunting and riding equipment . Combs, belt parts, a bronze bangle, a glass bead and disc brooches were found from the area of costume and personal care . In the kitchen area there was a kettle hook with a chain, a tripod for cooking and dishes. Among the tools there were hatchets and ax blades. Spinning vortices, weaving shuttles and flax flakes for processing flax came from the household sector. There were turned parts under the scrap wood. 11 pieces of antler were found between the 4th and 7th centuries. The cuts and saw marks on it indicated the work of bone carvers on site.

Find investigations

Ore and metal

The pieces of ore and slag found during the excavations, which could be dated to the 3rd to 7th century through ceramic finds, were archaeometrically examined, which provided important insights into the history of mining in the Harz. The investigations were carried out as chemical analyzes and microscopic examinations for mineralogy. After that, iron, lead and copper smelting was already in operation in Düna at this early stage. There was iron and non-ferrous metal slag as well as foamed slag from iron extraction. In the case of individual ores, the Rammelsberg deposit in the Harz Mountains could be determined beyond doubt using a scanning electron microscope . Thus, the earliest smelting of non-ferrous metal ore from the Rammelsberg could be proven from the 3rd century. Until then, it was assumed that mining would begin on Rammelsberg in 968 , as Widukind von Corvey first mentioned this in his Res gestae Saxonicae . According to this, Otto the Great "opened silver veins in the Sachsenland" ("in Saxonia venas argenti aperuit"). In order to smelt the ore from Rammelsberg it had to be transported to Düna. The shortest distance over the Harz is about 30 km as the crow flies, around the Harz in flatter terrain the distance is about 50 km.

The structure of the Upper Harz ore differs significantly from the Rammelsberg ore and was also smelted in other ways. Smelting sites were found here where silver mining from Upper Harz ores from the 3rd or 4th century AD can be documented and proven.

Three furnace plates found could be dated to the 9th and 10th centuries with archaeomagnetic investigations, whereby the results were checked with the archaeological findings. The lead plate connected to a furnace plate is attributed to the time around the year 800.

A numismatically examined coin pendant made of bronze was classified as around 1048. Since it was in an archaeologically determined layer of fire, it is suspected that the stone building was destroyed during the Saxon uprisings around 1070.

Wood

15 pieces of wood found were examined dendrochronologically . They could not be dated absolutely because the edge of the forest was no longer there or they were deformed. In addition, there were no regional chronologies from the Harz region. The woods could only be determined relative to each other, after which they were felled at a time interval of up to 20 years.

plants

Plant remains were found in great numbers and diversity during the excavations. They are well preserved due to their closed position in wet sediments on two watercourses with a high groundwater level and clayey subsoil. By archaeobotanical studies on plant debris, the medieval vegetation conditions in the area of the settlement could reconstruct the stream. In addition to cultivated plants, weeds and wild plants were found. Cultivated crops were cereals such as rye, wheat, barley and oats, whereby rye was of great importance as in other desert areas. Flax and poppy seeds were grown on oil plants. Cultivated fruits such as apples, plums and sweet cherries were only found to a small extent. Wild fruits, such as raspberries, blackberries, wild strawberries and elderberries, played a larger role in the diet of the inhabitants of that time.

The medieval vegetation conditions in the area of the settlement on the brook, which was used as a garbage dump, could also be reconstructed using plant remains. During the 3rd to 7th centuries, the stream bed was lined with woods that accompany the stream, such as black alder and hazel bushes. In the second settlement phase from the 8th century, rather low, annual pioneer plants grew. Later it was herbaceous bank and reed plants.

literature

- Lothar Klappauf : The excavation of an early medieval manor in Düna / Osterode , in: Reports on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony , 4/1982

- Lothar Klappauf: Prospecting, findings and finds in Düna / Osterode, summary of the colloquium on 9/10 September 1983 , in Reports on the Preservation of Monuments in Lower Saxony. 4/1983

- Düna / Osterode - a mansion from the early Middle Ages. In: Lower Saxony State Administration Office - Institute for Monument Preservation (Ed.): Workbooks for Monument Preservation in Lower Saxony. Issue 6, Hildesheim 1986

- Lothar Klappauf: Archaeological results and archaeometry in Düna , in: Reports on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony. 3/1987

- Lothar Klappauf, Friedrich-Albert Linke: Düna I. The stream bed before the construction of the representative stone building. Basics of settlement history. In: Material booklets on the prehistory and early history of Lower Saxony. Issue 22, Hildesheim 1990

- Lothar Klappauf: Excavation of the early medieval manor of Düna / Osterode , in: Excavations in Lower Saxony. Archaeological monument preservation 1979–1984. Stuttgart 1985

- Lothar Klappauf, Friedrich-Albert Linke, Frank Both: Excavation Düna, from the edge of the Harz to the deposits In: Mamoun Fansa , Frank Both, Henning Haßmann (editor): Archeology | Land | Lower Saxony. 400,000 years of history. State Museum for Nature and Man, Oldenburg 2004. Pages 329–332.

Web links

- Entry by Stefan Eismann about the manor in Düna in the scientific database " EBIDAT " of the European Castle Institute

- Brief description at Harzarchäologie.de

- Settlement history of Düna

- Excavation photo of the stone building (It started with Düna - mining history of the Harz for 3000 years)

- Reconstruction drawing of the medieval manor in Düna between streams with unrealistically high water levels by Wolfgang Braun

Individual evidence

- ↑ Firouz Vladi : The geological subsurface of the desert of Duna and structural geological drilling investigations of the former relief. In: Düna / Osterode-a mansion of the early Middle Ages.

- ↑ Erhard Kühlhorn: The medieval devastation in southern Lower Saxony. Volume 1: AE. Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 1994, ISBN 3-89534-131-2 , pp. 429-431.

- ↑ Osterode.de - city information. Retrieved August 20, 2011 .

- ↑ Lothar Klappauf: Archaeological prospection, findings and discovery of the early medieval manor in Düna. In: Düna / Osterode-a mansion of the early Middle Ages.

- ↑ Reinhard Zölitz: Desert prospection with the help of phosphate mapping in Düna. In: Düna / Osterode-a mansion of the early Middle Ages.

- ↑ Friedrich Albert Linke: Applied excavation technology in Düna / Osterode. In: Düna / Osterode-a mansion of the early Middle Ages.

- ↑ Wolfgang Brockner / Hans Emil Kolb: Archaeometric investigations on ore and slag finds from the Düna excavation. In: Düna / Osterode-a mansion of the early Middle Ages.

- ↑ Lothar Klappauf: On the archeology of the resin. In: Reports on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony, publication of the Lower Saxony State Administration Office - Institute for Monument Preservation - Hanover. Issue 4/1992.

- ↑ Wolfgang Brockner: Early non-ferrous metal extraction in the Harz region. In: Reports on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony, publication of the Lower Saxony State Administration Office - Institute for Monument Preservation - Hanover. Issue 4/1992.

- ↑ Ulrich Willerding: First paleo-ethnobotanical results about the medieval settlement of Düna in Düna / Osterode. In: Düna / Osterode-a mansion of the early Middle Ages.

Coordinates: 51 ° 41 ′ 14.8 ″ N , 10 ° 16 ′ 50 ″ E