Huguenots in Berlin

The Huguenots in Berlin , Protestant religious refugees from France and their descendants, formed a numerically, economically and culturally significant minority since around 1700. The aftermath of this immigration continues to the present day.

The word Huguenot is an expression of controversial linguistic origin. It can be traced back to France for the first time in 1551; it was considered a dirty word before the Protestants called themselves that. In Brandenburg and Prussia the word was initially not used, here the refugees were called Réfugiés and their settlement area was considered a French colony. Only around 1900 did the use of the expression Huguenot gain acceptance in the German states .

prehistory

With the Edict of Tolerance of Nantes , France's King Henry IV was able to end the bloody conflict between Catholics and Huguenots, the French Protestants of the Calvinist denomination in his territory, in 1598 . The Protestants were guaranteed freedom of belief and the right to practice their religion under certain rules, the places they controlled were guaranteed as so-called “fixed places”, and they were also approved for civil service. The edict, however, did not guarantee that religions were really treated equally. The position of the Catholic Church as a state church was affirmed.

However, after the death of Henry IV the situation for the Huguenots changed again. New violent conflicts arose. Protestant strongholds such as La Rochelle were besieged and taken, the capitals of the Protestant south occupied. This was followed by extensive occupational bans and, from 1681, the notorious " dragons ": Dragoon regiments occupied the houses of Protestants across the country and forced them to renounce their beliefs, sometimes with extreme brutality. Finally, on October 18, 1685, in the Edict of Fontainebleau ( Edict of Revocation) , Louis XIV also formally revoked all the concessions his grandfather Henry IV had made to the Protestants in the Edict of Nantes - because, as the preamble said, “the better and greater part of our subjects from the said allegedly reformed religion adopted the catholic. "

All Protestant clergymen had to leave the country, many were banished to the galleys , all Protestant churches were destroyed. Believers were forbidden to practice their religion under threat of severe punishment, but it was also forbidden to flee abroad. The exodus of the Huguenots from France had already begun during the previous repression . A small number of them had also reached Berlin around 1670 , and they were mostly wealthy people who were quickly integrated as civil servants or officers. Now, after the Edict of Fontainebleau, despite the threat of punishment, a mass exodus of around 200,000 people developed (various sources give figures between 150,000 and 250,000), around 20 percent of the Protestant population in France.

General development

Immigration

About 40,000 Huguenots fled to the German territories, Brandenburg-Prussia took in almost 20,000 of them. The legal basis for the increased influx of Huguenots to Berlin and other Brandenburg areas was the Edict of Potsdam , which Friedrich Wilhelm , the "Great Elector", on October 29, 1685 (according to the Gregorian calendar, which was not yet applicable in Brandenburg at that time, on November 8), just a few weeks after the Fontainebleau decree. Its title: Chur-Brandenburg Edict, Regarding Those Rights, Privilegia and other Charities which Se. Churf. Pass through to Brandenburg to those Evangelical Reformers of the French nation, who will be graciously determined to settle in your country there . The elector justified the acceptance of the Huguenots with pity for his beleaguered fellow believers. The Brandenburg dynasty of the Hohenzollern had belonged to the Calvinist denomination since 1613, unlike the great majority of its Lutheran- Protestant subjects.

In addition to the religious, there were also important economic reasons for the edict. Brandenburg was devastated in the Thirty Years' War, which ended in 1648, by troops moving through, epidemics and famine had raged and the population was reduced dramatically. Cities and villages were in ruins, the economy was shattered. The consequences of the war were by no means over in 1685, and the funds were not sufficient for reconstruction either, as the state's income had decreased to the same extent. At the same time, expenditures for the military and representation grew. The Great Elector and his advisors sought a way out of this misery in a comprehensive " peuplication ", the settlement of as many economically efficient new citizens as possible - the acceptance of the Huguenots was just one example of the acceptance of those persecuted for religious reasons in Brandenburg-Prussia. The Edict of Potsdam was not primarily aimed at the better-off among the Huguenots - the preferred already developed countries such as the Netherlands or England - but at penniless but hard-working immigrants , especially those with skilled craft and business skills .

The transport of the refugees to Brandenburg was well organized and responsibilities were regulated. A committee of administrative experts who were already based in Brandenburg was put together: Court chaplain David Ancillon the Elder was responsible for refugees from the area of his hometown Metz , Louis de Beauveau , Comte de L'Espance, (1620–1688, Lieutenant General) for the area Ile de France , Henry de Briquemault (major General, Governor of Lippstadt) for the Champagne , Walter de Saint Blancard (François Gaultier de Saint-Blancard, 1639-1703, court preacher in Berlin) for the Languedoc , Claude du Bellay d'Anche ( Oberhofmeister) for the Anjou and Poitou area . The Brandenburg ambassador to Paris, Ezekiel Spanheim , helped many emigrants to leave the country.

The Réfugiés were accepted in collection camps in Amsterdam , Frankfurt am Main and Hamburg and were forwarded from there to the intended settlement locations. Here they were able to take advantage of a number of privileges and start-up assistance that were promised to them in the 14 points of the Edict of Potsdam. Freedom of belief and the practice of their cult in French by their own clergy were guaranteed, as well as a largely independent legal system, temporary tax exemption, free membership in guilds , granting citizenship , start-up financing for commercial start-ups, land and free building materials. A state “Commissioner for French Affairs” was available as a contact person upon arrival. With such far-reaching concessions, Brandenburg had gained a head start over other distressed German territorial states that were also trying to attract French refugees.

Between benevolence and rejection

In Brandenburg-Prussia, the immigrants settled mainly in places within a radius of about 150 km from Berlin, the largest French colony arose in the capital itself. There in 1700 out of a total of 28,500 inhabitants, about one in five French people who fled settled down mainly in the newly created cities of Dorotheenstadt and Friedrichstadt . They brought only a small amount of their own resources, so they initially had to rely on help. Since 1672 there was a French Reformed community in Berlin founded by the first, isolated religious refugees. The parish was the natural point of contact for the numerous new Réfugiés, but was hopelessly overwhelmed with the task of solving their immediate material need. Since even a collection among the local population did not bring sufficient funds, the elector ordered a compulsory levy on January 22, 1686, combined with the reassuring hint that this would remain the only levy of this kind.

The goodwill of the court, the nobility and most of the intellectuals was certain to the new citizens. The elector himself had finally invited them. French was regarded by the social elites of Europe around 1700 as an expression of a civilized way of life - the language of the Huguenots was therefore regarded as evidence of their cultural affinity. This was also the reason that some of them were appointed as tutors at court, such as Marthe de Roucoulle and Jacques Égide Duhan de Jandun . The common Reformed denomination in contrast to the Lutheran confession of the German subjects did the rest.

In contrast, the simple Berlin population was largely hostile to the French. Their appearance was strange, their language incomprehensible, the practice of religion foreign. When they arrived, housing and food became scarce, and prices rose as a result. Even more important: their own professional existence was seen in danger and the newcomers envied their privileges. So many obstacles were put in their way. The guilds refused to accept the strangers unhindered, there were cases of arson and broken windows by stones. Even the elector's general protection promise did not offer any reliable protection against harassment of this kind.

Demarcation

The Huguenots in Berlin and Brandenburg did not enter as a homogeneous group. They shared their religion, their fate as refugees and their language. But they came from very differently shaped regions of France - from the agricultural areas of the south or from the pre-industrial north - and this was also reflected in their lifestyle. Under the conditions of exile in an unfriendly environment, the groups soon moved together. Hardly anyone spoke German, close contact with German neighbors was rare, and marriages between Germans and French were virtually impossible. Above all, the French Reformed community offered a common base. Here they also defended themselves against hostility from the surrounding area, so recurring provocations by the French in churches that were used alternately by German and French communities have been handed down. Until the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714, most of them hoped to return to France.

They believed that they could best protect themselves against the negative attitude of the German environment through almost unconditional loyalty to the Brandenburg-Prussian authorities. This, in turn, was very helpful to their protégés in the semi-autonomous administration of their colonies. By around 1720, a specific special status had developed, a separate administrative apparatus headed by a chef de la nation , including a French senior directorate. The official language was French. A separate judicial system with three instances spoke law based on the French model. Laws were published in two languages, but only the French version was authoritative for the Huguenots.

Gradual integration

Acculturation is the term that is most often used in the literature for the further whereabouts of the Huguenots. It means: growing into a cultural environment, a change as a result of cultural contacts. This process was not one-sided. The economic and cultural achievements of the refugees, their religion and their language changed the German environment, in some cases permanently. The Huguenots themselves had to deal with far greater changes as a minority in a rapidly growing German population.

In terms of their customs and habits, they gradually adapted to their new surroundings, but held onto their native language for a relatively long time - the most important element of their group identity alongside religion. French remained a status symbol for the ruling class. Craftsmen, merchants, day laborers and service personnel had to learn German in order to be able to keep up with everyday working life; After a transition period, the language of the ancestors was lost in these social classes. French lasted the longest in worship and church. After preaching in French until the 19th century, the practice of holding church services alternately in both languages established itself. Church registers have only been kept in German since 1896.

Between 1696 and 1705, 80% of the marriages were among the French population. This changed in the second, even more so in the third generation . Here, too, the bourgeoisie among the Huguenots behaved rather conservatively, while mixed marriages between workers in the factories soon became the norm. In the second half of the 18th century the ratio was almost reversed: 70% of the members of the French colony married German partners. The established Berliners gave up their rejection - it was recognized that the “newcomers” had far more advantages than disadvantages and, in addition, they liked previously unknown or less common products such as wheat beer , asparagus and finer salads. The first well-visited public garden restaurants were opened by Réfugiés around 1750 near the Brandenburg Gate . Many Germans even tried to be accepted into the French colony, because this gave them legal advantages. Fewer and fewer Réfugiés spoke French, and more and more Germans used it, often more badly than right (see below).

Model patriots

In 1785 the French colony celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Edict of Potsdam at great expense. The ruling house of the Hohenzollern was thanked in festive church services and in festivities, but their own achievements were also emphasized. The grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the immigrants saw themselves as a group of important French cultural bearers and at the same time as Prussian patriots who were unreservedly loyal to the state. This self-image was only seriously put to the test once: during the time when Berlin was occupied by Napoleon's troops from 1806 to 1808 and again in 1812/13 . At that time, not only the Prussian or French identity was under discussion, but when the new urban order came into effect in 1809 as part of the Prussian reforms ( Stein - Hardenberg reforms), the Réfugier colonies lost their privileged special status after more than a hundred years. Integration had progressed so far that many French Reformed parishes, now the only institutional bearers of the special Huguenot identity, dissolved. The existence of the remaining communities also appeared uncertain.

But around 1870 a countermovement began. With the "Réunion" and the "Huguenot Wednesday Society", two associations were founded in Berlin that were intended to strengthen the endangered feeling of community. Newly created magazines such as “Die Kolonie” pursued the same goal. The growing ties to the Prussian state had more of an effect on the common denomination. The highlight of the Huguenot renaissance was the 200th anniversary of the Edict of Potsdam in 1885. Various publications celebrated the success story of the “Refuge” and affirmed the unwavering loyalty to the state authority.

This self-portrayal of the Huguenots also corresponded to the image that those around them made of them. Otto von Bismarck is said to have called them "the best Germans". This assessment continued into the National Socialist era . " The Huguenots, who came to the Reich from France at the time, [represent] a particularly positive selection of the best Germanic blood ..." read a letter from the party leadership of the NSDAP to the consistory in 1941 . Conversely, Richard Lagrange, pastor of the French Church in Berlin, had already declared in 1935 on the 250th anniversary of the Edict of Potsdam: “ Nobody should surpass us in their love for our Führer [ Adolf Hitler ] and for this our German people and country . “The Huguenots were not treated differently at that time and did not behave any differently than the great majority of the German people.

Today's descendants of the Réfugiers can define themselves as Huguenots either primarily through their religion or through a specifically historical awareness - if that is so important to them at all. For the first group, as it was 300 years ago, the French Reformed congregation is the central place of group identity. The others see themselves as Huguenots mainly because of their own family history or because they generally have a lively relationship with the history of French religious refugees. The German Huguenot Society - founded in 1890 as the German Huguenot Association - offers them an institutional framework.

Special aspects

Economical meaning

With the Huguenots, experienced farmers, gardeners and artisans came to Berlin and Brandenburg, specialists who had already belonged to the elite of their professional groups in France. They brought with them knowledge and modern production techniques that had not previously existed in Brandenburg. There was an above-average number of skilled workers from the textile trade : cloth makers, wool spinners, hat, glove and stocking weavers , dyers, tapestry and silk weavers , linen printers , hat makers and others. Wig makers, cutlers, watchmakers, mirror manufacturers, confitiers and pâtissiers settled here, as well as bookbinders , enamellers , pastry bakers , cafetiers , but also merchants, doctors, pharmacists, civil servants and judges were among the Réfugiés, while the Brandenburg army was made up of 600 French officers and 1,000 soldiers reinforced.

Silk manufacture

The authorities had high hopes for a group of experts in mulberry trees and the breeding of silkworms . They were supposed to create the conditions for the production of high-quality silk fabrics suitable for export in Prussia. In 1716 they were assigned a settlement area north of the Spree , in today's district of Moabit , Friedrich Wilhelm I himself noted on a site plan: "Here you should plant mulberry beets." The colonists also received initial capital to procure the plants, but it turned out to be Ten years of effort that the barren, partly sandy, partly boggy soil did not allow sufficient yields over the long term. Attempts at other sites were similarly disappointing - several cemeteries in the French colony had been planted with mulberry trees and mulberry hedges. In Moabit, Réfugiers then grew fruit and vegetables with greater success, and their asparagus was particularly popular in Berlin.

Manufactories

Manufacturing in Brandenburg received a strong boost from the Réfugiers. Two examples are first of all the sugar production by Johann Caspar Coqui and Ludewig David Maquet in Magdeburg , after Achard's development work or the tobacco production there by Georg Sandrart . For Berlin, on the other hand, the serial production of tapestries was of particular importance. Until the end of the 17th century, tapestries were still a French domain. Aubusson (Creuse) in the Limousin, for example, was awarded the title of royal manufactory in 1665 because of the excellent quality of the tapestries made there. The two artist families, the Barrabands and the Merciers, were active there. From these two tapestry families, a number of Réfugiers found themselves in Berlin, among them Pierre I Mercier and his brother-in-law Jean I Barraband . Immediately after arriving in Brandenburg in 1686, Mercier applied to the Great Elector for a patent for the production of tapestries and received it in the same year. Thereupon he founded, together with his brother-in-law Barraband, a manufacture in Monbijou Castle, which operated under the name "Mercier and Barraband". This manufactory produced tapestries with gold, silver, silk and wool of very high quality. The series of six tapestries based on designs by court painter Rutger von Langenfeld, which the French colony gave to Elector Friedrich III to glorify the wars of his father (the Great Elector), the patron of the colony, became particularly well known.

The manufactory also survived difficult times. Jean I Barraband was followed by his son Jean II Barraband after his death (1709) . In 1714, after Pierre I Mercier left Berlin for Dresden, Barraband initially continued to run the factory on his own. At this time the famous "Chinese series" was created; Carpets with motifs from the Far East. An example of this is “The Audience with the Emperor of China”. The motifs often corresponded to the originals from the French carpet weaving Beauvais , which speaks for the continued lively relationship between the French Huguenots and their country of origin. In 1720, Jean II Barraband founded his own carpet knitting factory with Charles Vigne as a partner, which created new motifs, often based on pictures by Antoine Watteau .

General considerations

The economic ventures of the French were not always as successful as hoped - and as they were portrayed in the often glorifying historiography, especially in texts by the Huguenots themselves. Recent research shows that the factories often bypassed the market. They offered high-demand products in large quantities, for which there was insufficient demand and purchasing power in the new, predominantly rural area with little capital . In many cases, the state start-up aid had to be repeated two or three times or the state itself acted as the buyer. By electoral disposal of 1,698 goods were of Huguenot production of export exempt duties, while the import of similar products by punitive tariffs was hampered, in order to protect the manufacturers in the country from foreign competition. Despite such aid, a large number of French companies did not survive the period of government funding. However, there were also a number of very successful establishments; and it was undeniably the Huguenots who provided decisive impulses for the development of efficient manufactories and more modern economic conditions in their new homeland.

The church

Church organization

Just like the secular authorities, the highest church authority of the French Reformed congregations in the country, the consistoire supérieure des communeautés réformées françaises (1701–1809), was based in Berlin. This higher consistory took the place of the national synod , which was actually prescribed as the highest authority according to the French Reformed church order . In Brandenburg-Prussia, however, the Prussian rulers reserved the right to stand at the top of the church hierarchy as summi episcopi (supreme bishops ) . At the parish level, there was a committee of elders, deacons and clergy who were responsible for church discipline and parish administration. Because the French Reformed Church attaches great importance to diaconia and the school system, a close-knit network of social and school activities developed in the colonies. In 1817 the French Reformed parishes became part of the newly founded Evangelical Church in the Royal Prussian Lands , which initially united Lutheran and Reformed parishes under one organizational roof. In the period that followed, there were also theological approaches, but the French community has retained its own reformed profile to this day.

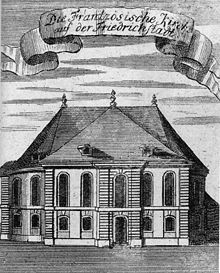

The first church building

The first church of the French Reformed community in Berlin was built in Friedrichstadt, on today's Gendarmenmarkt . In 1699 the community turned to the elector about building a church, and he had a plot of land assigned to it the following year. The first master builder after the laying of the foundation stone on July 1, 1701 was the colonel and civil engineer in the Brandenburg service, Jean Louis Cayart . He had also provided the design, modeled on the Temple in Charenton , a building that had a high symbolic value for the Huguenots as an important meeting place near Paris and had been completely destroyed after the Edict of Revocation in 1685. The construction of the church was financed almost exclusively by collecting money in the French colony, and parishioners also undertook all construction work. The interior of the building was very simply furnished, as it corresponded to the Reformed view. The French Friedrichstadtkirche was consecrated on March 1, 1705 . Because it was outside the ramparts , an order was issued on July 29, 1705, according to which the fortress bridges had to be lowered at the beginning and at the end of the service of the French congregation in order to enable the visit of the church to those living inside the fortress ring.

The French Cathedral (Church and Huguenot Museum)

In 1708 the German Church, built around the same time as the French Church, was completed on the south side of the market. Between 1780 and 1785, both churches received their towers designed by Carl von Gontard , more attached to the church buildings than connected to them. The designation of the towers as a French or German cathedral does not refer to a church function, but to their domes (French dôme ). In the 19th century, the French cathedral school was located in the rooms of the tower . It was set up by the French community as a six-class (elementary and) middle school on the north side (facing Französische Strasse) for boys and on the south side (facing Jägerstrasse) for girls. In the years 1905/06 the French church was rebuilt under the direction of Otto March , its floor plan remained unchanged, the facade and interior got a neo-baroque decor according to the taste of the time. After a renovation in 1931, the French Cathedral housed the Huguenot Museum as well as the archive and library of the French community. The church and the tower dome burned down in World War II . The structural element below was spared the fire because of the concrete ceiling that was drawn in in 1930. The services of the French Reformed congregation took place there from 1944 to 1982. After 1945 the rescued holdings of the Huguenot Museum and the library were returned. The church was rebuilt until 1983 and 1987 respectively. As the only one of five historic churches of the French Reformed community in Berlin, it is currently still used liturgically . Today it serves both the French Reformed congregation and the United local congregation as a place of worship. Since the Wall was built in 1961 , church services for the French Reformed congregation have also been held in the so-called Coligny Hall in a tenement building in the west of the city, in the Halensee district .

In the Allied air raids on May 7, 1944, the nave and on May 24, 1944 the tower dome burned down .

Social facilities

As early as January 1686, the “French Hospital” ( Hôpital français ) was opened, a hospital and old people's home for destitute réfugiers. After the “Temple de la Dorothéenstadt” , various social institutions of the French colony emerged in Friedrichstadt. Necessary new buildings were erected in the Friedrichstrasse 129 district acquired in 1710 . In 1780, the children's hospital ( Petit Hôpital ) , which had been in existence since 1760, was housed . From 1699 to 1873 there was a soup house and cookshop ( Marmite ) and the poor bakery ( Boulangerie des pauvres ) at different locations . Both belonged closely together - the head of the bakery was also responsible for the preparation of meat and bouillon - they provided needy old people, sick people and those who had recently given birth with the most essential food. A “French wood company” ( Societé française pour le bois ) had the task of distributing firewood to destitute members of the community every year before the beginning of winter. The French Orphanage ( Maison des Orphelins ) was opened in 1725, it existed as an independent institution until 1844 and was then merged with the Children's Hospital and the so-called School of Mercy ( École de Charité ). This school for the children of the poor started its work in 1747. French and the subjects of the Prussian elementary school at the time, i.e. religion, German, arithmetic and drawing, were taught; In addition, the students had to do practical work, partly as preparation for later employment, but partly also to improve the difficult financial situation of the school. The three institutions for needy children and young people lasted until the 20th century, during the inflation in the 1920s they had to be closed due to financial problems. The Prussian finance officer Pierre Jérémie Hainchelin (1727–1787) was the first director of the French Timber Company, director of the French orphanage and the “École de Charité” in Berlin.

Lack of money was a constant problem in maintaining social institutions. The report of a preacher to the Prussian government describes the plight in the first half of the 18th century: “In our Friedrichstadt there is an immense poverty ... many hundreds (move) their clothes little by little, live on it until they have nothing left to wear that they cannot go to church or anywhere else. With the lack of beds and clothes they get sick easily ... and finally die miserably. ”Nevertheless, the committed social care and medical care by qualified doctors, pharmacists and midwives in the colony meant that life expectancy was higher and child mortality was lower than among the German population.

Huguenots in culture and science

A large number of Huguenots contributed to the development of culture and science in Prussia. Some of them are mentioned here as examples. French booksellers and publishers played an important role in Berlin's intellectual life. Robert Roger, printer and bookseller in the service of the Elector, published the first French books in Berlin. In 1690 he published a story about the French colonies in Brandenburg, written by Charles Ancillon , the judge and director of the colony in Berlin. The bookstore of Étienne de Bourdeaux was the Berlin center for French literature in the Age of Enlightenment around 1750 .

In 1700 the Prussian Academy of Sciences was founded, initially under a different name. The theological , literary and scientific working groups of the Huguenots had formed a preliminary stage. Throughout the 18th century, an average of 10%, at times even almost 30% of the members were Réfugiers. Étienne Chauvin published the first scientific journal in Berlin, the Nouveau Journal des Sçavans . The theologian, philosopher and historian Jean Henri Samuel Formey (1711–1797) was a member of the academy for almost 50 years, he was editor of the Nouvelle Bibliotheque Germanistique and a collaborator at the Encyclopédie Diderots . Friedrich Ancillon (1767-1837) was a preacher since 1790 in Berlin, was in 1803 Academician, 1809 State Council and in 1810 tutor to the Crown Prince, later King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Even the librarian of Friedrich Wilhelm IV , Charles Duvinage was a Huguenot and enthusiastic Scientist. He had a lot of correspondence with Alexander von Humboldt , many of the letters have still been received. The important mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707–1783), born in Switzerland , was appointed to the academy in 1741 by Friedrich II . He stayed in Berlin for 25 years, wrote numerous mathematical treatises, headed the academy's observatory , was a member of the board of directors of the École de Charité and was responsible for accounting for the colony's social institutions. Francois Charles Achard (1753-1821), physicist and chemist , was appointed director of the physics department of the academy in 1782. He developed the technical basis for the industrial production of beet sugar . Maturin Veyssière de La Croze worked as a linguist and librarian.

Architects from the ranks of the Huguenots such as Jean Louis Cayart , Carl von Gontard , Jean de Bodt , David Gilly , Friedrich Gilly and Paul Ludwig Simon were involved in the expansion and beautification of Berlin and in representative and technical buildings in the Mark Brandenburg. The popular, extremely productive draftsman and engraver Daniel Chodowiecki had provided designs for the architectural sculpture of the French Cathedral. He came from Danzig and came to Berlin in 1740, where he married the daughter of a Huguenot gold sticker. In 1764 he became a member of the Akademie der Künste , and was its director in the last years of his life. Peter Joseph Lenné , the busy garden architect of Classicism , was accepted as an honorary member of the Academy of Arts. Louis Tuaillon was a well-known Berlin sculptor on the threshold of modernity. Outstanding writers with a Huguenot family background include Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué , Willibald Alexis and Theodor Fontane .

The French grammar school

"This grammar school is unique in the world," said François Mitterrand when he visited Berlin in 1987. The history of the French grammar school in Berlin had a decree from Elector Friedrich III. started on December 1, 1689: “For the purpose of educating the children of the Réfugiers, we have decided to establish a grammar school at our expense, in which ... the children not only educated in the fear of God and good morals, but also free of charge in Latin, in the Eloquence, philosophy and mathematics are taught so that one day they can serve the state. ”Initially, directors and teachers came exclusively from the ranks of the réfugiers, and the language of instruction was French. Individual teachers also contributed through lectures outside of school or through scholarly publications to familiarize their German fellow citizens with French intellectual life. After just a few years, additional German students were accepted, for whom school fees had to be paid. At first some children came from circles around the court, by 1800 two thirds of the students were Germans. In the 19th century the grammar school developed into an elite school.

After the Second World War, there were temporarily two French-speaking grammar schools in Berlin - the traditional Huguenot school and a second grammar school that had been newly established for the children of members of the French occupying forces. The two were merged in 1952 under the official name “French Gymnasium - Collège Français”. Since then, the Berlin Senate has been responsible for the institution, the French state pays the French staff and provides teaching materials . The curricula are very much based on the French curricula. Current location of the school - the ninth since its inception - the Derfflingerstrasse is in the district of Tiergarten of the district center . About half of the students have French as their mother tongue. In school, German and French students experience French not only as the language of instruction in most subjects, but also as a colloquial language. The aim of the lessons is to prepare students for the German Abitur and the French Baccalauréat .

French in the Berlin dialect

The influence of the French language on the dialect of Berliners can be traced back to two main reasons: the admission of the Huguenots in 1685 and the occupation of the city by French troops at the beginning of the 19th century. As early as the 18th, and even more so in the 19th century, the use of French temporarily became a fashionable quirk . In a text from 1831, the author criticizes: "... all the ridiculousness that fashion and imitation produce emerge quite vividly when you have to ask yourself bœuf à la mode or bœuf naturel in French to satisfy your German hunger with German beef." Complaints of this kind relate, however, to the excessive use of French by relatively linguistic Germans, i.e. mostly members of the so-called better classes.

The vernacular took over fashion on a different level: individual words or phrases were borrowed and based only on the sound of the spoken word. Distortions were inevitable, if only because the French did not always speak standard French, but often the regional dialects of their former homeland. If such words or phrases were then in use for a long time, they diverged further and further from the original form. Despite this, the French origin is still recognizable in many cases. Boutique (the shop) becomes Budike, estaminet (the small tavern ) becomes Stampe, clameur (the shouting) becomes slapstick , pleurer (cry) to blare. Polier is derived from parlier , the speaker or spokesman for a work column . Être peut-être (to be in doubt) developed into etepetete, from avec force (powerful) to brisk.

In other examples, the French origin can no longer be recognized. The expression "Kinkerlitzchen" originated from quincailleries ( haberdashery , little things). From mocha faux high Prussian import duties on coffee in the 18th century prompted French Gardener, - (false coffee) "Muckefuck" was chicory ; grow, their roots were roasted, ground and added to thin coffee infusion as an additive The French called the result café prussien , café allemand or mocca faux . This also applies to the adjective “all” (meaning “something is all”, e.g. the wine is all or has run out), which is derived from allé (gone).

(Unfortunately, the source is missing for all of these examples. Apart from Budike , forsch and Muckefuck (doubtful here), the etymological derivations are not generally accepted; the Kluge derives Stampe from the verb stampfen (in the sense of dance), Klamauk as onomatopoeic Formation of the Radau or pardautz type , Polier from Latin politor , etepetete as a reinforcing reduplication of ndd. Ete ("adorned"), Kinkerlitzchen from initially Ginkerlitzgen with ultimately unclear origin and all as a probable change in construction from eg "the potatoes are all consumed ”to“ the potatoes are all . ”For Muckefuck , which was first attested in the Rhineland, he rather considers dialectical Mucke (“ Mulm ”, i.e. wood that has crumbled into powder) and fuck (“ lazy ”) to be the origin of mocca faux .)

literature

- Manuela Böhm (Ed.): Huguenots between migration and integration. New research on the refuge in Berlin and Brandenburg. Metropol, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-936411-73-5 ( review ).

- Gerhard Fischer: The Huguenots in Berlin , Hentrich & Hentrich Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-941450-11-0 .

- Werner Gahrig: On the way to the Huguenots in Berlin . Verlag Das Neue Berlin, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-360-01013-2 .

- Eduard Muret: History of the French colony in Brandenburg-Prussia, with special consideration of the Berlin community . Berlin 1885.

- Gottfried Bregulla (ed.): Huguenots in Berlin . Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung Berlin, 1988. ISBN 3-87584-244-8

- Johannes ES Schmidt, The French Cathedral School and the French Gymnasium in Berlin. Edited and commented by Rüdiger RE Fock. Publishing house Dr. Kovac Hamburg, 2008. ISBN 978-3-8300-3478-0

- Laurenz Demps : The Gensd'armen Market. Face and history of a Berliner Platz . Henschel Verlag, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-362-00141-6 .

- Ewald Harndt: French in Berlin jargon . Stapp Verlag, Berlin 1977/1987, ISBN 3-87776-403-7 .

Web links

- Ursula Fuhrich-Grubert: On the history of the Huguenots

- Martin Thunich: You came just as requested . Huguenots in the economy of Brandenburg-Prussia . (PDF; 2.3 MB)

- hugenotten.de - Website of the German Huguenot Society e. V. with information on the history of the Huguenots and literature references and various links

- Website of the French Church in Berlin with information on history and community life

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dirk Van der Cruysse: Madame is a great craft, Liselotte von der Pfalz. A German princess at the court of the Sun King. From the French by Inge Leipold. 14th edition, Piper, Munich 2015, ISBN 3-492-22141-6 , p. 337.

- ↑ Ursula Fuhrich-Grubert: "On the History of the Huguenots", Chapter 2.1 ( Memento from August 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Götz Eckardt (ed.): Fates of German architectural monuments in the Second World War. A documentation of the damage and total losses in the area of the German Democratic Republic. Volume 1. Berlin - capital of the GDR, districts Rostock, Schwerin, Neubrandenburg, Potsdam, Frankfurt / Oder, Cottbus, Magdeburg . Henschel, Berlin 1980, p. 6 f. (with pictures).

- ↑ Publications of the private website Renald Schmidts hugenottenviertel.de

- ↑ Neil Jeffares: Louis Vigée. In: Dictionary of pastellists before 1800. London 2006; online edition (keyword “Jassoy”) (accessed September 25, 2014) pastellists.com

- ^ Renate du Vinage: Librarian of the kings Friedrich Wilhelm IV. And Wilhelm I of Prussia. The life story of Charles Duvinage (1804-1871). With an edition of his correspondence with Alexander von Humboldt. Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt 2005.

- ↑ Origin of French parler, however, also in Bernhard Kytzler, Lutz Redemund: Our daily Latin . 7th edition, Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2007.

- ^ Friedrich Kluge: Etymological dictionary of the German language. 23rd ext. Edition, edited by Elmar Seebold. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995.