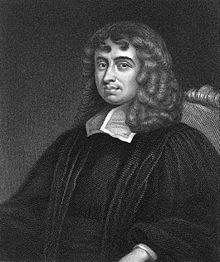

Isaac Barrow

Isaac Barrow (born October 1630 in London , † May 4, 1677 ibid) was an English clergyman, scholar and mathematician .

School and study

Isaac Barrow was born in London in October 1630, the son of the wealthy linen cloth merchant Thomas Barrow. His mother died in 1634 and he grew up with his grandfather. His father gave him a good education first at Charterhouse College, where he was noticed as a troublemaker and do-not-do-well. His father then sent him to a school in Felstead in Essex with more strict discipline, which he attended from 1640 and where he learned Greek, Latin, Hebrew and logic. In the last school year, his father could no longer pay the school fees due to financial losses, but the headmaster Martin Holbeach kept Barrow due to his excellent performance and used him as a tutor for Thomas Fairfax. From 1643 he studied at Peterhouse College in Cambridge, where his uncle was a fellow . In the turmoil of the English Civil War, he had to leave Cambridge after his uncle Isaac lost his post due to his loyal views and Barrow went to Oxford, where his brother was a cloth merchant. During the siege of Oxford by loyal troops, he went to London in 1644 (Barrow was also a royalist like his father). During this time he was dependent on the support of friends. In 1646 he was back in Cambridge and was tutored by the Regius Professor of Greek James Duport (free of charge as both were royalists and because of Barrow's talent). Mathematics was little cultivated in Cambridge at that time, which Barrow also criticized in his speech after his bachelor's degree (BA) in 1648, with which he successfully applied as a fellow. In 1652 he obtained his MA ( Magister Artium ) degree (with a dissertation on Descartes and his natural philosophy), whereby he escaped expulsion from the university several times due to his royalist views only just by the intervention of the college director Thomas Hill. He studied a wide variety of subjects such as medicine, languages, astronomy (as a result of his preoccupation with church history), philosophy and geometry (which he mainly taught himself through self-study), even if his scholarship obliged him to turn to theology at the end. He became College Lecturer and University Examiner, the Regius Professorship for Greek as the successor to Duport, for which he was considered the most suitable candidate, he did not receive because of his political views in 1655.

to travel

A simplified edition of the Elements of Euclid by Barrow was published in 1655, and the English translation (1660) became a widely used textbook in Great Britain well into the 18th century. In the same year 1655 he went abroad on a university scholarship and studied in Paris , where he met Gilles Personne de Roberval and found the patronage of the London merchant John Stock (to whom he later dedicated his Euclid edition), and went to Florence , where he especially studied the coin collection in the Medici library, which made him a coin expert and later provided him with additional income as an appraiser. During his eight-month stay in Florence he met the Galileo disciple Vincenzo Viviani . A stay in Rome was broken up because of the outbreak of the plague and so he embarked for Istanbul , but was attacked by pirates on the way (Barrow played an active part in defending them) and spent seven months in Smyrna before spending a year and a half with the British Ambassador Thomas Bendish spent in Istanbul and studied the Orthodox Church there. In 1658 he traveled back to England via Venice (where a fire on the ship destroyed his belongings), Germany and the Netherlands and arrived back in Cambridge in September 1659.

Professorships

In the meantime, a king (Charles II) was installed again in Great Britain (1660). Barrow was ordained in 1659 and received another bachelor's degree in theology in 1661. In 1660 he became Regius Professor of Greek , which he had been denied a few years earlier, mainly because of his royalist views. He was supported by the Master of Trinity College John Wilkins. In addition, he accepted the professorship for geometry at Gresham College in London in 1662 (to which Wilkins recommended him), which he remained until 1663. He also held a substitute professorship (Locum) for astronomy. The Regius Professorship was poorly paid and the holder of the chair was originally not allowed to accept any other posts, which Barrow was able to relax a little. In 1661 he was able to keep his Fellow status due to a decree as Regius Professor.

After the Lucasische Chair for Mathematics was established in 1663 , Barrow switched to this in 1664 and gave up his Regius professorship for Greek. In the same year he gave up his ordination (for unknown reasons) - the Lucasian professor was exempted from the actually mandatory ordination for professors due to a special declaration that Barrow obtained. He gave his first mathematics lectures in the spring of 1664 and continued them until 1667, interrupted by longer periods when the university was closed due to the plague . His most famous student was probably Isaac Newton . In 1668/69 Barrow gave lectures on optics (mainly geometric optics), which Newton probably also heard.

His optics lectures (Lectiones Opticae) were published in 1669, the geometry lectures (Lectiones Geometricae) in 1670 and mathematics lectures (Lectiones Mathematicae) in 1683. Editing of the lectures was not done by Barrow, but by John Collins , Newton (optics lectures) and other students. The geometry classes are likely to include material from his classes at Gresham College. They deal with material from Archimedes, Apollonios and Theodosios (Sphaerica) and a treatment of tangents that inspired Newton's development of calculus.

Further career

In 1669 he resigned from the Lucasian chair to hand it over to his student Isaac Newton, whose talent he recognized. Barrow turned from then on from mathematics and made other career. According to a royal decree he was made Doctor of Divinity in 1670 and royal chaplain in London in 1669 (he also received a post as a kind of canon (prebend) by the Bishop of Salisbury ) and in 1673 by the king appointed head (master) of Trinity College in Cambridge, the king called him the best scholar of England. In this role he tried to limit the royal influence on the college and laid the foundations for the later construction of the library by Christopher Wren , with whom Barrow was friends and who therefore worked as an architect for free. He also became vice-chancellor of the university from 1675. In April 1677 Barrow traveled to London, where he fell ill with a fever and died a few days later on May 4th in Suffolk House . He tried unsuccessfully to heal himself through a combination of opium and fasting, as he had done earlier in Istanbul. He was buried in Westminster Abbey .

Personal

He never married and also removed the obligation to marry from his Trinity College Masters degree. He is said to have been small and slim and pale in appearance, sloppy in clothing and a heavy smoker, but strong and known for his courage. He was deeply religious and was considered to be very conscientious, but with his quick wit he could keep up with the most notorious bon vivants at the court of Charles II. With the Earl of Rochester the following contest of courtly manners ensued near the king's chamber: Rochester All yours, Doctor, up to the knee , Barrow, bowing deeper All yours, your lordship, up to your shoelaces , Rochester: Yours, Doctor, to the ground , Barrow Yours, your lordship, to the center of the earth . After the reply from Rochester Your Yours, Doctor, to the depths of Hell , Barrow let it go: I must leave you there, your Lordship

plant

He was later best known as the teacher of Isaac Newton , although the exact relationship between Newton and Barrow is not clear. Derek T. Whiteside doubts a teacher-student relationship, although Newton probably attended his lectures, and suspects that closer contact only came about relatively late (after 1667) (Newton published his optics lectures in 1669). In Newton's early manuscripts Barrow is not mentioned and even later Newton could only bring himself to admit an influence of Barrow's generation of geometrical figures through the movement of points or lines, only to add that he did not consciously remember it.

Barrow also played a role later in Newton's life, thanks in particular to his influence that Newton as a Fellow of Trinity College did not have to take religious vows (by changing the statutes of Trinity College in 1676), which made it impossible for him to remain in Cambridge since he was secretly an Arian . Barrow also communicated Newton's early work on analysis to other mathematicians such as John Collins and presented Newton's reflecting telescope to the Royal Society in 1671.

From Barrow comes the method of the characteristic triangle , which was only later named by Leibniz , to draw tangents on curves, which makes him one of those who contributed to the beginnings of differential calculus. Behind the construction was a geometric version of the fundamental theorem of analysis , which Barrow did not formulate explicitly. He applied the method many times and also found a formula for variable transformation in a certain integral and solved differential equations with separation of the variables .

With his knowledge of the connection of tasks via tangents and integration (area determination) and with his dynamic understanding of the geometry of curves and surfaces (curves as moving points and surfaces as moving curves) he had a great influence on Newton. Whiteside (in Dictionary of Scientific Biography ), however, denies a greater influence of the lectures on geometry and sees in Barrow's lectures little originality and predominantly a compilation and adaptation of other authors. Barrow's tangent method, in his own words, arose from a reference to such a construction by Marin Mersenne and Evangelista Torricelli , which he had heard of but had not disclosed, and was inspired by Roberval. Other influences in his lecture were his reading of James Gregory , Torricelli, Descartes, Frans van Schooten , Johan Hudde , John Wallis , Wren, Fermat , Christian Huygens , Blaise Pascal .

He had a conservative view of mathematics, by which he primarily understood geometry. In his view, algebra was more a part of logic (as a useful analytical tool) and not part of mathematics itself (and his Lectiones Mathematicae only the indispensable preliminary stage to his main work, the Lectiones Geometricae). His lectures were considered difficult to understand, which still found its echo in the history of mathematics by Nicolas Bourbaki , who complained that there were 180 figures on 100 pages in his lectures, whose analysis would be essential for understanding his arguments.

He also developed a simple form of the lens grinder formula .

In 1675 he published an annotated edition of the first four books on conic sections by Apollonios, as well as works by Archimedes and Theodosius of Bithynia .

He was best known to his contemporaries for his sermons, which were published posthumously from 1683 to 1689 by John Tillotson (Archbishop of Canterbury). According to Derek T. Whiteside, they were characterized by clarity and bluntness, but were too literary and convoluted to make him popular as a preacher.

Honors

Barrow was a founding member ( Original Fellow ) of the Royal Society of London in 1662 , which held its first meeting in 1663. But he was never particularly active in the Royal Society, so that one even considered his exclusion, as he also did not pay the membership fees at times.

In 1935 the lunar crater Barrow was named after him.

literature

- Derek T. Whiteside : Barrow, Isaac . In: Charles Coulston Gillispie (Ed.): Dictionary of Scientific Biography . tape 1 : Pierre Abailard - LS Berg . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1970, p. 473-476 .

- Mordechai Feingold (Ed.): Before Newton: The Life and Times of Isaac Barrow. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge 1990. (with contributions by M. Feingold on biography and Michael S. Mahoney on mathematics)

- Mordechai Feingold: Newton, Leibniz, and Barrow too: an attempt at a reinterpretation. In: Isis. Volume 84, 1993, pp. 310-338.

- PH Osmond: Isaac Barrow, his life and times. Society for promoting Christian knowledge, London 1944.

- Wladimir Arnold : Huygens and Barrow, Newton and Hooke. Birkhäuser, Basel a. a. 1990, ISBN 3-7643-2383-3 .

- Antoni Malet : Barrow, Wallis and the remaking of seventeenth century indivisibles. In: Centaurus. Volume 39, 1997, pp. 67-92.

Individual evidence

- ↑ His father is said to have refrained from making him a merchant and prayed that if God would take a son for him, it would be Isaac, based on the story of Isaac and Abraham in the Bible. Rouse Ball: Short account of the history of Mathematics. 4th edition. 1908.

- ↑ Euclid was subject matter, he was also familiar with the Euclid Commentaries by André Tacquet , Pierre Hérigone and William Oughtred , whose notation he later used in his Euclid edition, studied Archimedes , whom he later dealt with in his lectures, and probably Apollonios of Perge and Claudius Ptolemy (after Whiteside: Barrow. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography. ).

- ↑ Written after Whiteside, probably at the beginning of 1654. He brought out an expanded new edition in 1657

- ^ Whiteside: Barrow. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography.

- ^ Biography of Robert Nowlan, pdf

- ↑ These lectures have not been preserved except for the inaugural lecture. After Whiteside, they may have dealt with perspective and projections, which were mentioned as Collins' work titles.

- ↑ Barrow biography. Retrieved March 14, 2018 .

- ^ Whiteside in Dictionary of Scientific Biography. suspects that he - since he was apparently always robust health during his lifetime - died mainly from the dosage of his drugs

- ^ Rouse Ball: Short account of the history of Mathematics. 4th edition. 1908.

- ^ I am yours, doctor, to the knee strings. Barrow (bowing lower), "I am yours, my lord, to the shoe-tie." Rochester: "Yours, doctor, down to the ground." Barrow: "Yours, my lord, to the center of the earth." Rochester (not to be out-done): "Yours, doctor, to the lowest pit of hell." Barrow: "There, my lord, I must leave you." , Foreword to Barrow's Sermons, Gutenberg Project

- ↑ He even calls it a myth

- ^ Whiteside: Barrow. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography.

- ↑ Newton's biography in the Newton Project

- ^ Biography of Barrow in Wolfram

- ↑ Vladimir Arnold: Huygens and Barrow, Newton and Hooke. Birkhäuser 1990, p. 41.

- ^ Whiteside: Barrow. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography.

- ^ Bourbaki: Elements d´Histoire des Mathématiques. Springer Verlag, 1984, p. 238. Whereupon Wladimir Arnold could not avoid pointing out in his book that in Bourbaki's writings there was not a single drawing on 1000 pages and he strongly doubted whether that would be better. Arnold: Huygens and Barrow, Newton and Hooke. Birkhäuser 1990, p. 40.

Web links

- Literature by and about Isaac Barrow in the catalog of the German National Library

- John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson : Isaac Barrow. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive .

- Publications by and about Isaac Barrow in VD 17 .

- Isaac Barrow in the Mathematics Genealogy Project (English)

- Barrow at the Galileo Project

- Grave in Westminster Abbey

- Entry to barrow; Isaac (1630-1677); Classical and Mathematical Scholar in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- Tripota - Trier portrait database

- Spektrum.de: Isaac Barrow (1630–1677) May 1, 2017

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Ralph Widdrington |

Regius Professor of Greek at Cambridge University 1660–1663 |

James Valentine |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Barrow, Isaac |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English clergyman and mathematician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 1630 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 4, 1677 |

| Place of death | London |