John McDouall Stuart

John McDouall Stuart (born September 7, 1815 in Dysart , Fife , Scotland , † June 5, 1866 in London ) was a Scottish geometer and explorer who was the first European to cross the Australian continent from south to north and back.

resume

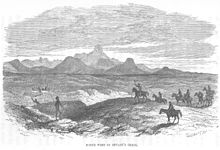

In several attempts between 1858 and 1862, he managed to find a way through over 3000 kilometers of desert and savannah from Adelaide in the south to Chambers Bay (near Darwin ) on the north coast of Australia - the decisive basis for the construction of the overland telegraph line of South Australia via Alice Springs to Darwin, which adheres closely to Stuart's route and was completed in 1872.

Stuart is one of Australia's great historical figures. While his first expeditions were aimed at finding agriculturally usable land, mineral resources and the hoped-for large freshwater reservoir in the interior of the continent, a strategic goal later came to the fore: a race was underway among the colonies for the order for the telegraph line, Australia the deep-sea cable from Java should connect and thus connect with the world. Adelaide was only able to stay in this race by opening up an overland route to the north. Those who won from the cities of the southeast could become the telecommunications hub of all of Australia, with all the expected economic and social benefits.

Origin and early years

McDouall Stuart was born in Dysart near Kirkcaldy on the north side of the Firth of Forth , the fifth son of nine children of Army Captain William Stuart, who was retired at birth, and his wife Mary, a née McDouall . His parents died when he was a teenager . Relatives enabled him to train at the Scottish Naval and Military Academy in Edinburgh , which he graduated as a civil engineer in 1838 . Then he decided to emigrate to Australia.

At the end of 1838 he registered as a passenger on the "Indus", which sailed to Australia. Stuart was skinny and relatively short (1.68 m tall and a little over 50 kg) and not in the best of health. He may have had undiagnosed tuberculosis. At least it is said that he vomited blood several times during the long crossing from Scotland to South Australia.

In January 1839 he arrived in the state of South Australia and soon found a job as a surveyor in Adelaide . A little later he bought his own instruments and dealt intensively with the outback , the geology and geography of the country. His best friend became William Finke, who made his living trading real estate and later financed Stuart's expeditions together with James Chambers, one of Stuart's customers and also a good friend. Chambers, along with his brothers James and Benjamin, had made wealth through horse trading and a postal company; they had their lands inspected by Stuart before they bought them.

After Stuart discovered copper at Oratunga Ranch in 1854 , Chambers and Finke bought a mine and invited Stuart to join the business,

“... but he was too restless to settle down permanently. He hated having to sleep in the house, didn't even want to spend two nights in the same place. New country had become his passion and his business ... ( ... but he was too restless to settle down. He hated sleeping indoors, and did not even like to camp in the same place for two nights. New country had become his great passion , as well as his business ... . ) "

Nevertheless, in 1843, when the surveying jobs were running out, Stuart tried his hand at being a farmer, but was accordingly happy when Charles Sturt soon afterwards offered him to take part in one of his expeditions to the interior.

Exploration of the continent

The cartographers and explorers George William Evans (1780-1852) and John Oxley had the route of Gregory Blaxland (1788-1852), William Charles Wentworth (1790-1872) and William Lawson (1774-1850) to the early 19th century Blue Mountains and after Bathurst recorded and maps of the inner Australian plains made. Oxley also explored the south coast of Queensland while Allan Cunningham ventured inland in 1827. One of the participants in this expedition was Charles Sturt , who between 1829 and 1839 discovered the main tributaries of the Murray-Darling Basin , which is now the agricultural heart of Australia. Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell confirmed Sturt's findings and in 1836 opened the route from New South Wales to the fertile land in the western part of Victoria .

The hinterland of the coast of Western Australia was mapped by Sir George Gray (1799-1882) and Edward John Eyre . The German naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt led three expeditions, in 1844 from Darling Downs in Queensland to Port Essington in the Northern Territories and on December 10, 1846 his second expedition began , on which he tried to cross Australia from east to west. It had to be abandoned after five months. His third expedition, to cross Australia again from east to west, failed fatally: Leichhardt did not reach his destination, the Swan River in the west (today in Western Australia) and was lost.

Only John McDouall Stuart was able to advance inland in 1860 and finally cross the continent completely from south to north in 1862.

Charles Sturt as a mentor

Stuart took part in an expedition by Charles Sturt from August 1844 to December 1845, the aim of which was to find a freshwater sea suspected in central Australia. In August 1844, the 17-person expedition, equipped with eleven horses, a draft horse, 30 oxen, 200 sheep, six dogs, four wagons and a collapsible boat, set off from Adelaide inland. Sturt discovered Coopers Creek and advanced northwest into interior Queensland . Instead of the presumed freshwater sea, however, he found only desolate and dry land, and the expedition turned into a disaster when it was stuck in the desert for six months.

Right at the beginning the expedition was attacked by hostile Aborigines , but Sturt managed to appease them. The group passed Broken Hill , but did not discover the quartz eruption on the rock formations (an unmistakable sign of mineral resources ). Further north, at the Rocky Glen near today's town of Milparinka , a gorge in which a narrow trickle broadened into a river, they were trapped because of the extreme heat and lack of water. Since they could hardly find any fresh food, many participants fell ill with scurvy . Deputy expedition leader James Poole blackened skin and peeled pieces of skin from his mouth. It got so hot that the thermometer shattered and the river threatened to dry up completely. The crew dug an underground room as a shelter. They also suffered in winter because it was bitterly cold. Sturt's eyes worsened to almost total blindness.

Before the situation threatened to become completely hopeless, it rained heavily, and the situation visibly improved, so that Sturt decided to continue the expedition.

Poole succumbed to his illness a short time later, and Stuart was promoted to assistant expedition leader. He drew most of the maps because Sturt was unable to do so because of his vision problems. The group crossed Strzelecki Creek and reached a wilderness which they named Sturt's Stony Desert . The horses were lame, and the cattle and sheep's hooves were worn down to the raw flesh from the sharp stones.

Today we know that this desert is 80 km wide. They crossed it and came to the Simpson Desert , where they were faced with 30 meter high sand dunes . Stuart realized that there was no getting ahead. He had to return to Fort Gray. The expedition had traveled 1,500 kilometers without success.

The result of the expedition was bleak, and Stuart's health was so bad that he could not work for more than a year. He established himself as a private appraiser in the countryside near Adelaide, where his services were in great demand. He examined land for minerals, possible mineral resources and water resources and assessed its suitability as grazing grounds and for livestock. From 1846 to 1858 he served numerous customers and there was no shortage of well-paid jobs. Nevertheless, he did not become prosperous, he spent his money as it came in.

“Sometimes he would go to Adelaide and 'throw' one happy party after another. He never cared how quickly he was spending his money. When it was used up, he took another job ... ( ... Sometimes he went to Adelaide and gave gay parties. He never cared how quickly his money was spent. When it was gone, he went back to his surveys. ) "

The expeditions

After his return and recovery, Stuart worked as a surveyor again until 1858, but also stayed for some time in Port Lincoln and tried his hand at real estate brokerage - again on the recommendation of his friends and again not too successfully .

He dreamed of his own expedition to look for good grazing land and mineral resources inland. Due to his participation in Sturt's expedition of 1844/45 and his long experience as a geometer, cartographer and surveyor, he felt up to the challenge. He knew about the difficulty of exploring desert areas with no water resources with large expeditionary groups and surviving in the outback, had experienced first-hand the fatal effects of scurvy , which Aborigines and their behavior can study and was familiar with the topography of the Australian interior. He was quick, he was flexible, and he had the special gift of being able to “read” an unknown landscape and to find water. That is why, unlike other expedition leaders, he wanted to travel with minimal effort and few staff.

In 1858 the time had come, with the financial support of William Finke, Stuart was able to prepare his first own expedition.

May to September 1858

The aim of the expedition was to look for pastureland and mineral resources north of Lake Torrens and Lake Gairdner . Stuart started out from Oratunga Ranch on May 14, 1858 with an assistant named Barker and an Aboriginal tracker. They were equipped with six horses, a compass, a clock and food for six weeks.

Past Flinders Ranges they headed west and passed the south coast of Lake Torrens. Then they turned north, where Stuart discovered a group of semi-permanent waterholes he called Chambers Creek (now: Stuart Creek), which became an important base for later expeditions. Further north-westerly they reached Coober Pedy (without discovering the vast opal field there) before a lack of food and fodder forced them to return south on the edge of the Great Victoria Desert .

On August 3, the Aborigine "deserted", but informed whites settling at Mount Eyre that two men in the desert were close to starvation. With almost completely used up food, without water and with lame horses, Stuart and Barker fought their way to "TM Gibson's Outstation", which they reached on August 22nd. After ten days of rest, they returned to Adelaide, where they received an enthusiastic welcome.

This expedition established Stuart's good reputation. He had explored a vast area of 40,000 square kilometers at a minimal cost, making important discoveries and insights. But the expedition also cost the participants a lot of strength and health.

“The trip was a terrible drag. ( I've had a terrible rough trip .) "

The Royal Geographical Society awarded him a gold watch. He left his diary and the maps he had drawn to the government of South Australia, for which they promised him 2,500 square kilometers of land from the explored area. However, he was never given this land due to political bickering, in which also opponents of Chambers and Finke were involved.

“Eventually, it turned out that his only honor was the gold watch from the Royal Geographical Society in London. As it turned out, however, his only reward for this journey was a gold watch from the Royal Geographical Society in London. "

April to July 1859

After recovering from the first expedition, Stuart applied for the lease of land around Chambers Creek. As a discoverer he was entitled to do so, but he wanted rights to a larger area. To end the negotiations in his favor, he offered to do the land survey himself.

With three men and 14 horses, he set off again in April 1859 to the north and reached today's border between South Australia and Northern Territory . Although still well equipped with water and food, the expedition returned more than 100 kilometers because they no longer had any horseshoes - an extremely important item in this stony region.

On this occasion, Stuart discovered another reliable water supply for future advances inland: a "beautiful spring" fed by the then unknown Great Artesian Basin .

“I have baptized her Source of Hope. The water is a bit brackish, but not from salt, but from baking soda, and it forms a powerful jet of water. I've lived on far worse water than this. It is of the utmost importance to me and leaves me with a path of retreat. I can now get from here to Adelaide at any time of year and in any climate. (I have named this The Spring of Hope. It is a little brackish, not from salt, but soda, and runs a good stream of water. I have lived upon far worse water than this: to me it is of the utmost importance, and keeps my retreat open. I can go from here to Adelaide at any time of the year, and in any sort of season.) "

November 1859 to January 1860

Chambers dreamed of crossing the continent from south to north. The as yet unexplored inland area was only about 600 miles, since Stuart's northernmost camp was 500 miles from Adelaide and Augustus Gregory had reached the Victoria River from the north . Chambers asked the government for help, wanted £ 1,000 to equip the expedition and £ 5,000 as a reward if it was successful. For reasons that are not known, the government rejected the application and instead appointed the police inspector of South Australia, Alexander Tolmer (1815–1890), whose expedition (in which the young Frederick Henry Litchfield also took part) ended in chaos and had to turn back before she left the district.

At the same time, the government was in competition with other states to host the telegraph station for the transatlantic telegraph cable from India. Rich rival Victoria was about to set up the largest expedition in Australia's history to date. For its part, the government of South Australia put a price of £ 2,000 on whoever would find a north-south overland route for the telegraph line.

Stuart's expedition left Chambers Creek on November 4, 1859. He was accompanied by William Darton Kekwick, two other men and twelve horses. They found evidence of gold in the Davenport Range area. After three weeks of unsuccessful prospecting, his men rebelled and the expedition set out on their way back. On January 21, 1860 they reached Chambers Creek again, and Stuart paid off the men except for William Kekwick, with whom he had become friends and whom he said, “everything I could wish a man to be” (A man who had everything and was what I could wish for) described.

March to September 1860

On March 2, 1860, Stuart left Chambers Creek again with Kekwick and Benjamin Head, who had been recruited in the meantime. They had 13 horses and food with them for three months and were aiming for the center of the continent. When they reached Neales Creek, much of their rations were destroyed by heavy rain, so they had to cut their rations severely. On April 4th they reached a river that Stuart named after Finke. All three men had signs of scurvy and Stuart was blind in the right eye.

They followed the river to a mountain range which Stuart named after the governor Sir Richard MacDonnell. They advanced further north to a lake which he named Chambers' daughter Anna. On April 22nd, they camped in what Stuart had calculated to be the center of the continent. He called the two mile distant mountain Central Mount Sturt (later renamed Central Mount Stuart ) and set a flag, "which may be important for the natives a sign that the dawn of freedom, culture and Christianity has come for them too." ( and may it be a sign to the natives that the dawn of liberty, civilization, and Christianity is about to break upon them.)

For a month the group searched in vain for a route that would take them further north if there was sufficient water supply. When it began to rain in May, they came to Tennant Creek, where they set up a supply camp surrounded by impenetrable scrub.

It was only when Kekwick protested that Stuart decided to turn back. They returned to Chambers Creek two months later, sick and hungry.

The Royal Geographical Society honored Stuart again, this time with a medal. Such a double honor from the Society has so far only been awarded to Dr. David Livingstone experience. He was honored by the government with an official banquet in Adelaide and two modern rifles as a gift. Sir Richard McDonnell received him personally. However, he did not receive the suspended prize money.

November 1860 to September 1861

After Augustus Gregory had explored the interior of Australia in 1858, a committee was formed in Melbourne with government participation to organize an expedition to cross the continent. The following expedition by Burke and Wills started on August 20, 1860 in Melbourne. Since Stuart had left Adelaide in March, supposedly to reach the north coast, Burke saw his expedition as a race with Stuart. After a long and arduous journey they reached the Gulf of Carpentaria on February 10, 1861 - the first, because Stuart had only headed for the center of the continent and had already returned. On the way back, both expedition leaders died of malnutrition and exhaustion at Cooper Creek towards the end of June 1861 .

The Parliament of South Australia, however, unaware that Burke and Wills' expedition was under a bad star, offered a sum of £ 2,500 for a larger, armed and better equipped expedition to be led by Stuart. On November 29, 1860, Stuart was able to start again. He left Moolooloo with seven men and 30 horses and reached Goolong Springs on December 4th and Chambers Creek on December 12th. The horses were partly sick and could not be used. Some went blind, others died, so the group stayed in Chambers Creek until the end of the month, waiting for replacement horses to arrive on December 31, along with more men and another food reserve. So on January 1, 1861, Stuart was able to leave Chambers Creek with a dozen men, nearly 50 horses and food for 30 weeks.

It was midsummer and the worst time to travel. Soon Stuart was forced to send back two men and the five most exhausted horses. The heat was extreme and the group lagged behind their schedule looking for water and animal feed. On February 11th - the day Burke and Wills reached the Gulf of Carpentaria - they were still in South Australia. They reached MacDonnell Ranges with considerable difficulty when heavy rain set in, allowing them to venture north to a more convenient spot. They reached Attack Creek on April 24, 1861, this time without being prevented from advancing further by enemy tribesmen. At about the same time - unknown to Stuart's group, of course - Burke, Wills, and King arrived at their base camp at Coopers Creek to find it ravaged and robbed. Their fourth member, Charles Gray, was already dead.

Stuart planned to move northwest towards the Victoria River . While most of the crew were resting, Stuart made a series of scouting walks in that direction, but where progress was blocked by thick brush and the lack of water. Finally he found a water hole 80 kilometers north, where he moved the camp. Further northern advances were initially unsuccessful. When he put everything on one card and still sent the entire group north, he was rewarded with the discovery of a "wonderful blanket of water" 150 meters wide and 7 kilometers long. He named it Glandfield Lagoon (later renamed Newcastle Waters ) and let the group camp there for more than five weeks while scouting a northwest route that would lead them to the Victoria River and thus to the sea.

Food was scarce, humans and animals were in extremely bad shape. The local Aborigines were unkind, setting fires around the camp and frightening the horses, so Kekwick had to put up armed guards. On July 1, 1861, exactly six months after they left Chambers Creek, Stuart ordered the withdrawal. They made good progress in the relative coolness of the southern winter and reached populated areas in September. When Stuart found out on his return that Burke and Wills were missing, he immediately offered to help look for them. However, the rescue team had left a few weeks earlier and soon returned with news that seven members of the largest and best-equipped expedition in Australia's history had perished. This noticeably cooled the urge to explore and explore.

December 1861 to December 1862

Although Stuart had already led five expeditions into central Australia and crossed the center to within a few hundred miles without losing a man, the South Australian government was reluctant to sponsor a sixth attempt. Stuart himself no longer had any financial means. He continued his plans undeterred and was supported by the Adelaide public. Business people donated supplies and food, and three men volunteered. Nine expedition members left Adelaide at the end of October 1861 and gathered in Chambers Creek, while Stuart organized the supplies and tried to recover himself - meanwhile in bad health and suffering from a complicated hand injury.

Finally, the government made £ 2,000 available at the last minute on the condition that Stuart be accompanied by a scientist, and Stuart set off to join his team with botanist JW Waterhouse.

The team made rapid progress and reached Newcastle Waters on April 5, where they came into conflict with the Aborigines but were fortunate to find water so they could quickly move their camp north. The next section of the journey turned out to be more difficult. Stuart and his scouts made five unsuccessful attempts to find a route to the Victoria River. Eventually he chose a new north instead of the north-west route and was rewarded with the discovery of a series of small waterholes that led to Daly Waters , about 150 kilometers north of Newcastle Waters, which they reached on May 28th and after the new one Named Governor of South Australia.

Stuart's strength and stamina decreased noticeably, further attempts to reach Victoria River failed. On June 9, 1862 they reached the area already mapped by Gregory for the first time, and on July 1, a river, which Stuart assumed was a tributary of the Adelaide River. He named him Mary River after one of Chambers' daughters. Now they were only about 200 miles from the Adelaide River, which Lieutenant Helpmann had already explored by ship. On July 24, 1862, Thring and Stuart, who preceded the group as scouts, received their ultimate reward when they suddenly saw the blue of the Indian Ocean.

The next day, the crew hoisted the Union Jack on the highest branch of a tree. Months ago Elizabeth Chambers had embroidered Stuart's name on that flag. A document bearing the names and signatures of all the expedition members was buried in a tin can under the tree.

"South Australian Great Northern Exploring Expedition. The expedition team, under the command of John McDouall Stuart, reached this location on July 25, 1862, after crossing the Australian continent from the South to the Indian Ocean through the center. They left the city of Adelaide on October 26, 1861 and the northernmost colony on January 21, 1862. To commemorate this happy event, this flag was hoisted with his name. All well. God Save the Queen. (The exploring party, under the command of John McDouall Stuart, arrived at this spot on the 25th day of July, 1862, having crossed the entire Continent of Australia from the Southern to the Indian Ocean, passing through the center. They left the City of Adelaide on the 26th day of October, 1861, and the most northern station of the Colony on 21st day of January, 1862. To commemorate this happy event, they have raised this flag bearing his name. All well. God save the Queen! ) "

Nine months after leaving Adelaide, they made their way back. Many of their originally 71 horses were so weak that they were left at water holes on the way back; Stuart, who suffered from advanced scurvy and was nearly blind, had to be pulled behind two horses on a stretcher, but recovered enough to be able to ride again on November 26th when they reached Mount Margaret and with three members of the Expedition formed a vanguard that reached Adelaide on December 17th. He had brought back all of his men - most of them weak, many sick, but all alive - along with 48 horses.

The last few years

Stuart described his expeditions in "Explorations in Australia".

The book Explorations in Australia. The Journals of John McDouall Stuart , edited by W. Hardman, appeared in 1864.

Stuart returned to Adelaide exhausted and broken and never recovered from the hardships he had endured.

Robert Bruce wrote:

“I had previously seen the brave little man on various occasions when he was doing his job as a surveyor. He wore a full dark beard and a long dark blue frock coat with brass buttons, an item of clothing that was definitely out of style even then ... I would not have mentioned the coat, but since he had separated from it, I did not recognize him ... One day, as I was driving a herd of cattle down to Arkaba, I heard a sharp voice with a Scottish accent behind me. When I turned around, I looked into a pale, doughy face, dominated by a heavy mustache and tucked under a dirty palm frond hat, that peeked out from behind the gate. I had seen the plucky little man on several occasions previously when he followed his profession as a land surveyor, and wore a full dark beard and rather long-tailed blue coat with brass buttons, a garment even then going muchly out of fashion. Stuart of course considered the long-tailed blue became him, or he would not have worn it, and I must say it was very appropriate. I should not have mentioned the coat in question had not the discarding of it and the assumption of dirty moleskin pants and frayed vest of uncertain pattern, worn over a bulging crimson shirt, been the cause of my not recognizing the intrepid explorer on a certain occasion . One day I was drafting a mob of cattle in the Arkaba yard, a sharp voice with a Scottish accent accosted me from the fence, when I turned to see a pallid pasty-looking face, crossed by a heavy mustache, and roofed in with a dirty cabbage tree, peering between the rails. "

Bruce had also observed Stuart's passion for whiskey early on:

“It may have been lucky for Stuart that Angus G was at the train station when he arrived, because Frank M was not at home and I never bought whiskey myself, so the researcher would only have what he would have called a warm welcome have come to ... Since I had work to my ears at that time, I didn't stay - hicks! - until all the whiskey was drunk, but I - hicks! - left it to the two Scotsmen. Anyway, they both had a nice hangover the next morning. (It was perhaps fortunate for Stuart that Angus G was at the station when he arrived, for Frank M was from home and I never invested in whiskey, therefore the explorer might have had what he might have considered a dry welcome, but for Angus, as it was a vera wat nicht resulted fra 'the meeting, and baith got unco' fu '.… As I had my hands full of work about that time I didna wait to feenish the whusky, but left the two Scots to dae it. Anyhow, baith had sair heads the morn.) "

Stuart had received £ 3,000 from the government and had been given 1,000 square kilometers of grazing land free for seven years. But his health was bad, he felt lonely and restless. James Chambers had died and William Funke was sick. He himself was almost blind, had a crippled right hand, suffered from insomnia and could no longer ride or read. In April 1864, he traveled to Britain to recover. He moved to London to live with his sister Mary Turnball and her husband; his health should not improve any more.

“Within a year or two he was struggling with mental problems, confusion, memory problems, the inability to spell and, it seems, language difficulties that he was later described as 'semi-foolish'. Within a year or two he was to suffer confusion of mind, 'obfuscation', loss of memory, decline of the power to spell conventionally, and, it seems, difficulty of speech, and he was later to be described as having been 'half foolish ' "

Stuart died on June 5, 1866 at the age of 50. His death certificate lists the cause of death " softening of the brain and brain degeneration with a final cerebral brain hemorrhage" ( softening and degeneration of the brain with a final cerebral haemorrhage ).

Only seven people attended his funeral, four relatives, two envoys from the Geographic Society and Alexander Hay, after whom Stuart named Mount Hay in Central Australia. His grave is in Kensal Green Cemetery near London. The tombstone was erected by his sister Mary.

Telegraph line

Stuart's crossing of the continent was of particular importance for the development of Inner Australia, because an overland telegraph was set up in 1872 along his route, from Port Augusta in the south to Darwin in the north of Australia.

The overland telegraph was an infrastructural structure of epoch-making importance for Australia. He reduced the flow of communications to and from the British mainland from months to a few days and revolutionized the communication between the colonies and the rest of the world. Settlements grew out of the ground at the relay stations , engineers and workers from the telegraph company switched to agriculture after their work and built up the livestock industry, which to this day forms the economic backbone of the savannah areas of the Northern Territory .

Telegraphs were inexpensive to install. Heavy work equipment was not required, the main cost being the copper wiring. By 1851 there were more than fifty companies operating telegraph lines before many of them merged with Western Union around 1856 . Australia's first electrical telegraph connection ran from Melbourne to the nearby port of Williamstown , the first message being sent in March 1854. By 1858, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide were already connected, Tasmania followed a year later.

A global network of transoceanic and overland cables was already being created in the global planning. The line had already been led from Great Britain to India and should now also be led to Australia via Java. There was a race among the colonies to win the order for the telegraph line that would connect Australia to the Java deep-sea cable and thus connect it to the world.

By opening up the continent and finding a north-south route, the conditions for an overhead line were also created. In fact, the South Australian government built the Adelaide to Port Augusta telegraph line in 1870, sticking closely to the route Stuart had chosen.

The project manager Charles Todd opened the line on August 22, 1872 with the following message:

“Today, within two years, we completed a 2,000-mile communication line through the center of Australia, which just a few years ago appeared to be a desert as terra incognita. (We have this day, within two years, completed a line of communications two thousand miles long through the very center of Australia, until a few years ago a terra incognita believed to be a desert.) "

reception

Many places and sights are or were named after John McDouall Stuart, including:

- The city of Stuart, renamed Alice Springs in 1933 , founded in 1872 on the occasion of the construction of the telegraph connection, to this day the only larger city in the Australian outback with around 28,000 inhabitants, around 1,500 kilometers from all other large cities

- The Stuart Highway , briefly called The Track by the Australians and recently touted as the Explorer's Way by the tourist authorities, is Highway No. 87. It has a length of 2735 km and connects Port Augusta in South Australia with Alice Springs and Darwin in the Northern Territory . He follows the route of the telegraph line built in 1872 through the outback of the Red Center and the Top End.

- The Stuart Range, a plateau in Western Australia that runs parallel to the northern border of South Australia, with Central Mount Stuart as the highest point

- The Stuart Range Opal Field, now Coober Pedy

- The Stuart Range Observatory , opened in 1991, is located near the Bunya Mountains National Park , around 230 kilometers northwest of Brisbane

- A street in Canberra

- A statue of Stuart on Victoria Sqare in Adelaide

John McDouall Stuart, who was a Freemason ( Lodge of Friendship No. 613 in Adelaide ), remained a controversial figure in contemporary history:

“Lonely and independent, he was inspired by passion, pride and courage and subordinated everything to his great vision - the exploration of the Australian interior. His reputation for being a heavy drinker helped his contemporary opponents belittle his achievements and even doubt that he ever reached the Indian Ocean ... "

“Few other researchers in Australia in the 19th century were able to compete with him in his steadfastness, determination, perseverance, patience and heroic courage, which made him keep his goal in sight even after a long series of lost battles. Crossing the Australian continent through the center in the 1860s was a most brilliant undertaking, and doing it six times marked a hero of more than average height ... "

“It seems almost unbelievable that Stuart never lost a man on any of his expeditions, despite the harsh conditions in an extreme environment. It is equally interesting that this man, who knew how to move in the outback like no other, did not know how to orientate himself in city life. Addicted to alcoholism, Australia's greatest white explorer died in undeserved loneliness in 1866. "

literature

- John McDouall Stuart: Explorations in Australia . Indypublish.com 2005. ISBN 1-4142-7822-5 .

- Kirkcaldy Civic Society (Eds.): Kirkcaldy's Famous Folk: Adam Smith, Alexander Stewart, Thomas Carlyle, John McDouall Stuart, Thomas Elder and Family and Anna Buchan (O Douglas) . Kirkcaldy Civic Society 1996. ISBN 0-946294-02-X .

- Ian Mudie: The Heroic Journey of John McDouall Stuart. Angus and Robertson 1968

- Deirdre Morris: Stuart, John McDouall (1815-1866) . In: Douglas Pike (Ed.): Australian Dictionary of Biography . Volume 6. Melbourne University Press, Carlton (Victoria) 1976, ISBN 0-522-84108-2 (English).

- Edward Stokes: Across the Center: John Mcdouall Stuart's Expeditions 1860-62 . Allen & Unwin 1996. ISBN 1-86448-038-6 .

Web links

- The Journals of John McDouall Stuart

- The John McDouall Stuart Society Incorporated

- Australian outback. Planet-Wissen.de

- Taking it to the edge: Land: John McDouall Stuart. Government of South Australia, State Library

- Heroic exploration of Australia's vast interior Up from Australia

Individual evidence

- ↑ John McDouall Stuart (2002). [Online]: kidcyber.com.au

- ↑ Sturt described this expedition in 1848 in his book "Narrative of an expedition into Central Australia" books.google.de .

- ↑ John McDouall Stuart: Explorations in Australia fullbooks.com

- ↑ ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

- ^ Ian Mudie: The Heroic Journey of John McDouall Stuart , p. 105

- ^ John McDouall Stuart: The Journals of John McDouall Stuart ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

- ↑ For comparison: Burke and Wills, on the other hand, had a budget of £ 12,000.

- ^ John McDouall Stuart: The Journals of John McDouall Stuart ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

- ^ Monument Australia

- ↑ In fact, it was October 25, 1861

- ↑ ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

- ↑ Accessible online at ebooks.adelaide.edu.au, among others

- ↑ "cabbage-tree hat": A typical Australian hat made from the leaves of the Cordyline australis , an Australian palm

- ^ Ian Mudie: The Heroic Journey of John McDouall Stuart , p. 230

- ↑ adb.online.anu.edu.au

- ↑ Famous Freemasons ( Memento December 5, 1998 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The heart of Australia article in Freemasonry Today (No. 33 Spring 2016). On the website of the magazine www.freemasonrytoday.com (accessed April 21, 2016)

- ↑ adb.online.anu.edu.au

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stuart, John McDouall |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Australian geometer and explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 7, 1815 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dysart, Fife, Scotland |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 5, 1866 |

| Place of death | London |