John S. Williams

John S. Williams (* 1863 ; † January 26, 1932 in Milledgeville , Georgia Jail ) is the only white man convicted of the murder of blacks in the US state of Georgia between 1877 and 1966 . An all-white jury sentenced him in 1921/1922 for the murder of two blacks. He was also shown to have been involved in the murder of nine and allegedly in the murder of up to ten other blacks. All of the murdered were black people who worked in illegal debt bondage on his plantation . The reason for the murder was that Williams feared the workers would testify against him in a trial.

background

The reconstruction policy of Congress after the Civil War resulted in the 13th , 14th, and 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution , which enshrined the equality of black and white populations. A number of southern states issued so-called black codes after these years . These laws were aimed at the former slaves by subjecting them to new regulations and restrictions after their liberation from slavery and denying them basic rights. These black codes varied from state to state, but basically meant restrictions in the freedom of choice of profession, choice of place or choice of spouse and the prohibition of testimony or the limitation of the ability to give evidence in court. The Black Codes also provided the pretext for sentencing black people to several months' imprisonment on the basis of banal and regularly even fabricated allegations. Until 1928, when Alabama was the last US state to abolish convict leasing , people sentenced to prison were leased as cheap labor to plantations and companies, especially in the southern states. This applied to both colored and white convicts, but the great majority of those subjected to such criminal practice were black. On the plantations and in the mines or factories to which they were leased, they were largely defenseless and exposed to living conditions harsher than those experienced by enslaved people before 1860. While slave owners had an economic interest in maintaining the labor of their slaves, this incentive did not exist for the slave laborers.

In addition to convict leasing, illegal debt bondage was practiced in the southern states. Those convicted of fines who were unable to pay their fine were offered to pay the fine by entrepreneurs or plantation owners if they at the same time contractually agreed to work off the amount of money paid. After signing, their living conditions did not differ from those of the convicts leased through convict leasing. As Douglas A. Blackmon shows in numerous cases in his Pulitzer Prize- winning non-fiction book Slavery by Another Name , this system was used by a corrupt system of justice of the peace and sheriffs to provide the local economy with cheap labor. Again, it was primarily blacks who fell victim to this illegal practice, which Blackmon describes as a continuation of slavery by other means.

State attorneys such as Warren S. Reese attempted to end this practice using federal law in the early 1900s, but received no regional or national support in these efforts. It played a role that neither the extent nor the devastating living conditions of those exposed to this system were known to a wider public. African Americans, who suffered most from this practice, were unable to be heard due to discriminatory laws in the southern states. Warren Reese, for example, struggled to find witnesses to the brutality and injustice of this system because they feared for their lives or the lives of their loved ones. At the same time, there was little will at the federal level to enter into an open conflict with the southern states.

The John S. Williams case

John S. Williams was one of the plantation owners who used bondage contracts to get cheap labor. He owned a large plantation in Jasper County , some forty miles southeast of Atlanta, which he worked with three of his adult sons. The plantation owner was considered wealthy and influential.

In November 1920, a black worker by the name of Gus Chapman managed to escape forced labor on this plantation. In early 1921, he told federal employees at the United Federal District Court that he had been forced to work on the plantation under a bondage contract.

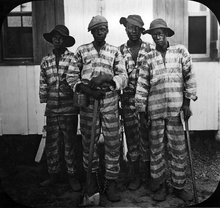

Investigating bondage incidents was not a high priority on FBI agents ' agendas , but two weeks after Gus Chapman's report, two agents traveling in the area on another investigation went to see John S. Williams' plantation to get an idea for yourself. They found eleven black workers apparently forced to work under bonded contracts. Their work was monitored by a 26-year-old black overseer named Clyde Manning. Interviewee John S. Williams said he was unaware that debt bondage was forbidden and described it as a common practice in the region. During a tour of the farm, the agents found evidence that the workers were chained at night. Interviewed workers, who appeared adequately fed and clothed, looked intimidated and were reluctant to respond to agents' questions, but said they were satisfied with their treatment. According to Douglas Blackmon, the two FBI agents left the farm saying that Williams would not face a lawsuit in federal court.

The murder of the eleven workers

Contrary to what the FBI agents indicated, Williams was at risk of possible prosecution and decided immediately after the FBI agent's visit to eliminate the black workers who could serve as witnesses in such a trial. The first to murder was Johnnie Williams, whom John S. Williams and his warden Manning killed in a remote pasture. John Will Gaiter was told to dig a new well the next morning. As soon as he had dug a sufficiently large pit, he was hit with a pick and then buried in the pit. On February 25, 1921, less than a week after the agents' visit, John S. Williams informed the remaining nine men that they were free to go. He offered two of the men, John Browne and Johnny Benson, that he would drive them to the nearest train station that night. Instead, Williams and Manning took them to a remote place and threw the men chained to a heavy iron wheel into the Alcovy River , where they drowned. The following night, Willie Preston, Lindsey Peterson, and Harry Price were similarly killed by Williams and Manning. A week later, Charlie Chisolm was drowned by Williams. Willie Givens was slain by Manning and Fletcher Smith was the last survivor of Williams to be shot. The FBI became aware of the murders after the drowned corpses were found.

The trial

Williams and Manning were tried individually in Newton County , and each was charged separately for each individual murder case. This was to ensure that they would be convicted even if they were not found guilty of a single murder. The trial of Williams began on April 21, 1921 and ended with a life sentence for the murder of two people . Manning testified as the main witness against Williams in the trial.

In the course of the trial and the accompanying reporting , it emerged that the brutal treatment of forced laborers on the Williams plantation in the region was not unknown. Williams ran his plantation like a brutal dictator . There was no evidence that any of the workers had managed to work off his debt. A worker who was forced to do forced labor on the plantation was credited with an annual wage of only 35 cents after deducting the cost of food and clothing. At night the workers were locked up in barracks and they were also regularly flogged for trivial reasons. On Sundays, Williams and members of his family would train their sniffer dogs by forcing workers to run through the woods and chasing the dogs after them. It also became clear that there had been murders on the plantation before 1921. At least four, but possibly ten workers were killed after trying to escape or refusing to work.

The trial against the 26-year-old Manning began on May 30, 1921. His defense lawyers pleaded for an acquittal : Manning had lived on the plantation since he was thirteen or fourteen and was unable to read or write. Besides him, his mother, siblings, his wife and young children lived and worked on the plantation. It became clear that resisting Williams' orders would have endangered his life and that of his family. Manning knew he would not have expected any help from the local police. In the course of the two-day process it also became apparent that Manning had almost no knowledge of living conditions outside of the plantation and Jasper County. When the court heard that two bonded laborers had fled Jasper County before they were captured and returned to the plantation, Manning argued that they fled US territory. Manning's sentencing to life imprisonment rather than death by hanging is considered evidence that the jury recognized his predicament.

Manning died of tuberculosis in 1927 , Williams died in an accident in 1932, both of whom were imprisoned at the time.

literature

- Douglas A. Blackmon : Slavery by Another Name: The re-enslavement of black americans from the civil war to World War Two . Icon Books, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-84831-413-9 .

- Pete Daniel: The Shadow of Slavery: Peonage in the South, 1901-1969 . UJrbana, Ill .: University of Illinois Press, 1972.

- Gregory Freeman: Lay This Body Down: The 1921 Murders of Eleven Plantation Slaves. Chicago: Chicago Review Press and Lawrence Hill Books, 1999.

- Donald L. Grant: The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia . Secaucus, NJ: Carol Publishing Group, 1993.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name , 2012, p. 364

- ↑ a b c d e f The John S. Williams Case on Murderpedia , accessed January 4, 2014

- ↑ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name. 2012, p. 377 and p. 378.

- ↑ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name. 2012, p. 360.

- ^ Mark Thorburn: John S. Williams and Clyde Manning Trials: 1921 - Murdering The "Evidence" Of Peonage. In: law.jrank.org. Retrieved January 31, 2014 .

- ↑ a b c Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name. 2012, p. 362.

- ↑ Blackmon: Slavery by Another Name. 2012, p. 363.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Williams, John S. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American plantation owner and murderer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1863 |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 26, 1932 |

| Place of death | Milledgeville |