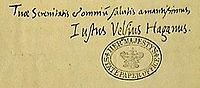

Justus Velsius

Justus Velsius, Haganus or Dutch Joost Welsens (* around 1510 in The Hague ; † after 1581) was a Dutch humanist , physician and philologist . Velsius began his career as a highly respected professor of the seven liberal arts in Leuven , Strasbourg and Cologne . Later he presented himself as a prophet and represented his own special view of Christianity , which he found in his book "Christiani Hominis Norma", which he wrote in Londonhad written, set out. He soon came into conflict with civil and ecclesiastical authorities throughout Europe and spent his last years as a preacher and faith healer in his native Holland . During his stay in Cologne, Velsius was married to Beatrix van Steenhoven and later to Grete Cassens in Groningen .

Life

After studying medicine and the seven liberal arts in Bologna , he received his doctorate in medicine in 1538 and settled as a doctor in Antwerp in 1540/41 . In 1541 he moved to Leuven, where he met the Portuguese humanist Damião de Góis and was on friendly terms with Andreas Vesalius . Although Justus Velsius did not have a job at a university, he began to give public lectures in Greek and Latin on philosophy , mathematics and Euclid in Leuven in 1542 . In an inaugural lecture he explained that anyone who wants to acquire a solid knowledge of mathematics should avoid the newer compendia of mathematics "like the plague" and instead turn to the authors of the ancient world . He referred to Euclid, Archimedes , Apollonius , Ptolemy , Nicomachus and Proclus among the Greeks, followed by Boethius , Jordanus Nemorarius and Witelo and, among the younger authors, Peuerbach and Regiomontanus . In 1544 he proposed to hold a course on Trapezuntios' "Dialectica". The authorities resisted, however, and in the ensuing controversy, they forced Velsius, whose theological integrity they looked suspicious of, to leave the university. In 1542 he failed in his endeavor to succeed Petrus Nannius (1496–1557), whereupon he went to Strasbourg in 1544 on the recommendation of Martin Bucer , after a short teaching stay at the Marburg Latin School and possibly also in Basel . In 1545 Velsius published the Greek text of Proklos' work "De Motu" (German: About the Movement ), along with a Latin translation.

Strasbourg

From Easter 1544 to 1550 Velsius taught dialectics and Aristotelian ethics as a collaborator of Johannes Sturm in the upper classes of the Strasbourg grammar school, the so-called Schola Argentoratensis (Strasbourg School) . On November 17, 1545, through the mediation of Bucer in the St. Thomas Church in Strasbourg, he received a canonical in the collegiate foundation . Some time before October 17, 1548 he married Beatrix van Steenhoven. When Velsius got into trouble because he had accepted the Augsburg Interim and the resulting conflict with his Protestant colleagues, he moved to Cologne in the spring of 1550; He probably did not give up his Strasbourg canonical until 1553.

Cologne

In 1550 Velsius appeared in Cologne with a large number of students. Since the Cologne council wanted to build a trilingual school based on the model of the Old University of Leuven, it took the favorable opportunity to win the outstanding scholar as a professor of Greek and Latin. Velsius was offered 100 pagamentary gulden or 50 thalers , a notch of wine and a dress for the first year . He was also offered to negotiate further conditions "if his studies and the university would increase through his diligence", whereupon he was entered on June 16, 1550 in the matriculation . In August 1550 he was appointed professor at the University of Cologne . Since he was married, however, he could not receive a preamble from the university, instead he was paid by the council. In the years 1551 and 1552 the remuneration was increased to 150 thalers at his request by the council, he was now also to teach mathematics and furthermore not to leave Cologne for five to six years. Velsius and his colleague Jakob Lichius , who was instrumental in founding the Tricoronatum grammar school , drafted guidelines for a curriculum of eight classes, similar to the humanistic curriculum of Sturm in Strasbourg.

Velsius participated in meetings of the Baptist in the Guild Hall of the bookbinder in the Pfaffengasse, where he u. a. met the printer and martyr Thomas von Imbroich (1533–1558). Velsius' philosophical writings, in particular his work “Krisis”, in which he contrasted the true Christian philosophy with the anti-Christian one and made numerous allusions to the sophisms of the theology professors, soon led to suspicion of heresy . On October 29, 1554, "Krisis" was condemned by the University of Cologne and Velsius' license to teach was revoked on December 11, 1554 (with confirmation of March 29, 1555) because he did not want to distance himself from his writing. Emperor Charles V , which at the instigation of Carmelite - Provincial Eberhard Billick (1500-1557) On behalf of the clergy and of the Cologne cathedral chapter had turned and the university, urged the Council vain to take action against Velsius, who was on 25 March 1555 had published his defense, "Epistola ad Ferdinandum". Only after Velsius tried to give a public lecture on the 5th chapter of the Isaiah in his apartment on April 18, 1555 and rejected Eucharistic adoration and celibacy , the magistrate banished him in April 1555. Velsius refused to go and went from December 1555 to the end of March 1556 voluntarily imprisoned in a tower , whereupon the inquisition proceedings for "the enthusiasm for rebaptism, the sacraments and other damned sects" were initiated against him. He asked his influential friend Viglius to support him, but Viglius refused to interfere. Badly offended by this refusal, Velsius apparently accused his friend of Protestant inclination and severed all ties with his former friend. Because of this precedent, in 1555 the council passed a comprehensive directive against all heretics .

The Dominican Johannes Slotanus († 1560) served as papal inquisitor for the ecclesiastical provinces of Mainz , Cologne and Trier against Velsius and three other prisoners, whom he referred to as Anabaptists. The Protestant princes , especially Christoph von Oldenburg , intervened before the council on his behalf. Since he had declared on December 19, 1555 to join the Augsburg Confession (AB), Velsius was protected by the recently concluded Augsburg Religious Peace . On the basis of this statement, the council met again to consider the further fate of the detainee. However, they did not want to comply with an application for release because the matter was in the hands of the Inquisition and only Archbishop Adolf von Schaumburg was authorized to intervene in the course of the judicial proceedings. He had stated that the process had to be carried out and then the verdict had to be implemented. The Council then that Velsius decided to all people casserole to avoid evening or morning, the quietly Greven was to deliver to the other prisoners. At the same time, however, the council had reservations about announcing the sentence to the defendant on the tower and therefore decided that this should be done on the square in front of the tower. But as soon as you notice that the people's rush to "this old man of justice" would be too dubious, the ruling should be published on the prison tower, "so that you can finally come to an end with this troublesome matter."

According to this judgment, Velsius was found guilty of a heretic , blasphemator and suspect of rioting by a legal verdict . On March 25, 1556, the council decided that the burghers , rent , wine and tower masters of the city prison towers should meet again to discuss how the pronounced sentence could really be carried out without error, “so that the man could be at peace may become single and his part in his sovereignty and his origins be broken ”. Velsius protested against this judgment, which was unsuccessful and so the council decided to remove him by force. On the night of March 26th to 27th, 1556, the judges of violence Johann von Breckerfelde and Johann Brölmann appeared in his prison, violently opened the door that was kept closed by the convict, put a gag in his mouth and led him to the Kunibertsturm . There he was expected by the mayor Arnold von Siegen , the rent master Constantin von Lyskirchen, some councilors , Greven and two lay judges . When Velsius refused to take an oath never to step onto the Bering of the city, he was brought ashore in a boat across the Rhine and on the other side in the Duchy of Berg . From there he came to Mülheim , where he wrote the " Apologia " addressed to Emperors Karl V and Ferdinand I. Slotanus replied in 1557 with the "Apologia JV Hagani Confutatio", in response Velsius wrote the "Epistolae" in September 1557, which was ultimately followed in 1558 by Slotanus' writing "Disputationes adversus haereticos liber unus".

Frankfurt

Velsius arrived in Frankfurt on July 15, 1556 , turned to the English pastor of the Church of England Robert Horne (around 1510–1579), a Marian exile and leading Reformed Protestant, and informed him of revelations about which he was conducting a public dispute wool. When he heard of the arrival of Calvin , who had come to settle conflicts within the refugee church , he offered to take the chair. He proposed to defend “free theological will” (not to be confused with free will ) against the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. The disputation with Calvin, Johannes a Lasco and Horne lasted two days; Velsius summarized his views with the words: "aut esse liberum arbitrium, aut Deum tyrannum esse" (German: "Either there is free will, or God is a tyrant").

In a letter to Philipp Melanchthon dated September 17, 1556, Calvin said:

“I was dragged here by the differences of opinion with which Satan has for almost two years now usurped the small church of our language that was established here and reduced it to such an extent that it must have disappeared, if not quickly remedied would. I've had no rest since I came to town, and as if I hadn't had enough occupation on the matter, a madman named Velsius, to whom you wrote twice, caught us in new foolishness. We only devoted two days to this obtrusiveness. Up until this point I was always distracted when I calmed down those differences of opinion that have long been deeply rooted. "

On April 15, 1557, Velsius was expelled by the council of Frankfurt.

Heidelberg

On August 5, 1557, Velsius enrolled in Heidelberg and received a license to give public lectures in philosophy. However, this license was revoked by the University's Senate in June 1558 by order of Elector Ottheinrich because he had disseminated theses directed against the Holy Scriptures . Velsius attacked the pastor of the Heiliggeistkirche , Johann Flinner, in his position on the Eucharist , sent him a series of theses on the new birth and free will and accused the pastor of being a false apostle and a misleading prince and the people. For what was said to be the little independent Flinner, the stay in Heidelberg became a burden and already on August 25, 1557 he had complained in a letter to Konrad Hubert with the words “it doesn't really work out here, God help”!

When Flinner had received the good news for him at the beginning of 1559 that he was appointed preacher at the Strasbourg Cathedral , he gave his farewell speech on February 5, 1559. He spoke of his vocation to the Palatinate, of his teaching, of his church life and civic life and ended the speech with a "Summa" Christian admonition about the community, taken from the tenth chapter of the Letter to the Hebrews . Velsius did not fail to take this opportunity to write him another letter of abuse , which, however, received little attention since the Lutheran theologian Tilemann Hesshus approved Flinner's sermon and many of his listeners asked him to have it printed. In November 1559 Velsius was after the intervention of Elector Friedrich III. the holding of private lectures was also prohibited and he was expelled from the university's senate.

In 1560 Velsius returned to Frankfurt, where he asked the city council for permission to print a book he had written with the title “Summa Christian Lehr und Leben”. Velsius' request was forwarded by the mayor to the responsible Lutheran pastors ( preachers ) with a request for inspection and examination, whereupon they reported on August 2, 1560 that the book contained theses that were directed against orthodox doctrine. In particular, they expressed concern that these teachings could lead to unrest in the city's foreign churches, as was the case, for example, with the Munster Rebellion when there was an uprising there in the 1530s. On March 18, 1561, the council ordered Velsius to leave the city for having had his book printed without permission. The innkeeper Hansen Braun, in whose house Velsius was staying, was instructed not to let him live in his house anymore.

In May 1561, Velsius was in Strasbourg. Here he wrote to Johann Flinner (who had returned from Heidelberg) as well as to the preachers and also to the council, and put forward 20 proposals, which were probably the same as those he had already announced in Heidelberg and Frankfurt. However, these were not accepted because they did not agree with the catechism used in Strasbourg at the time . A month later, in June 1561, Velsius was in Basel . He was luckier there, at least he could count on Sebastian Castellio , with whom he had previously corresponded, and on the advocates of tolerance like Martin Cellarius and Celio Secondo Curione . He submitted a summary to the University Council , which was examined on June 16. The council passed it on to the Faculty of Theology because it was outside their department. Martin Borrhaus proposed a number of theses for an academic disputation, but Velsius turned it down after the council rejected a public debate . On June 25th, Velsius traveled to Zurich , where he arrived the next day. He wrote to the council and Heinrich Bullinger replied on behalf of the council, pointing out that his criticism was incorrect as it was directed against Luther and the Roman Catholic Church . Velsius left town on July 4th. On August 1st, Velsius was back in Heidelberg, where he wrote one last time to Bonifacius Amerbach and Johannes Sturm . At the end of August 1561 he enrolled in Marburg and taught there for a few months at the medical faculty .

London

In January 1563, Velsius had crossed the English Channel to England , where he joined the Reformed Dutch Church Austin Friars (Dutch: Nederlandse Kerk Londen) in London . Again he looked for the argument, this time it was about Nikolaus Carinaeus, who at the end of October 1562 had become second pastor of the Dutch refugee church and in September 1563 fell victim to the plague in London. Carinaeus had explained his thoughts on being born again through Christ , which Velsius opposed by publicly developing his idea around March 1563 that the perfection of Adam on earth could be achieved after the inner rebirth has taken place in the individual . Velsius wrote a summary of his religion "Christiani Hominis Norma" (German: "The rule of a Christian man"), in which he explained his idea that man, like Christ, can become God-in-man through rebirth. He sent copies of his pamphlet to the Bishop of London Edmund Grindal , Secretary of State William Cecil and Queen Elizabeth .

He also wrote a letter to the French Ambassador announcing God's vengeance to all who refused to accept his proposals. In his letter to the Queen, Velsius claimed that his calling was miraculously confirmed. The ambassador's servant, Cosmus, fasted for five or six days, convinced that after his abstinence he would receive “illuminations a cœlo”. According to Grindal, he went insane in the end, so none of these miracles stood up to further investigation. Bishop Grindal wrote a rebuttal that showed that Velsius' teachings were against Orthodox teachings. Velsius was summoned before the Council of Churches, which consisted of Bishop Grindal, Robert Horne, now ordained Bishop of Winchester, and the Dean of St Paul's Cathedral , Alexander Nowell (c. 1517-1602).

Novell had an open discussion with Velsius asking him, on behalf of the Queen, to leave the kingdom . He lamented this in very rude words to the Queen and foretold the death of the Bishop of Winchester and other important public figures. On April 16, 1563, the Church Council Velsius in a public made discontinuation ridiculous, after which the reverse preacher not occurred in London. Velsius did find some followers in London, but this did not have any long-term impact on his teachings.

Groningen

Velsius crossed the North Sea again and went to Groningen, the northernmost province of the Habsburg Netherlands . On January 6, 1564, the Secretary of the City of Groningen, Egbert Alting, noted in his diary that Velsius had been expelled but had secretly returned.

Velsius had obviously been hoping for a long time that the Cologne council would allow him to return to the city. Carried by this hope, he sent the council a new pamphlet and added a special covering letter to it. Since the city had refused to accept the book and letter, it had to be clear to Velsius that he would probably never be able to return there. “Because, it says in the minutes of December 27th, Velsius from the city and the monastery of Cologne and extra fines catholicorum (German:“ outside the boundaries of the Catholic [Church] ”), the council did not open its letter and that Not wanting to accept little books. ”In 1570 he had nevertheless dared to enter the Bering of the city without permission , whereupon the council told him“ that as long as he was not reconciled with the Catholic Church (German: “reconciled”), he could not be tolerated in Cologne; so let him go away, otherwise the gentlemen of the council would lead him to a place where he should be kept safe. "

Apart from his brief trip to Cologne in 1570, he appears to have stayed in Groningen. In August 1574, Menso Alting wrote that Velsius had been imprisoned for religious reasons and had been imprisoned for several years, but without specifying this period. However, the authorities felt sorry for him because he was an older man and apparently depressed. They therefore suggested that he be released, also because of the hardship that imprisonment meant for him and his second wife, Grete Cassens. The proposal was examined by the governor Caspar de Robles , who then had a conversation with Velsius and then passed it on to the bishop, who in turn instructed the dean of the cathedral to examine the proposal. On August 24, 1574, the bishop approved the release of Velsius. However, he refused to leave the prison because he wanted to be released only by God's grace and not by human intervention. This unusual situation lasted until May 1575, when de Robles requested the evacuation of the prison as the adjacent castle had to be reinforced and prepared for the garrison.

In February 1577 an arrangement was drawn up for the debts he had incurred in Groningen. Shortly afterwards he moved to the Dutch provinces as a Protestant preacher, visiting Haarlem , Leiden , The Hague and Delft , some of these cities more than once. He seems to have roamed Holland for at least 2 years. In August 1577 he was in Delft and in September of the same year in Leiden, where he reappeared in September 1579. On a recent visit to The Hague, he turned to a body of the Dutch government on November 9, 1579 and declared that it had been completely wrong to start a revolt against their rightful master, King Philip II of Spain . Again, he doesn't seem to have received an official response. In 1579 he published his work “A wonderful and wonderful treatise that emanates from the Spirit of God” (Dutch: “Een seer schoon heerlijk uit Gods Geest voort gekomen tractaetgen”), of which, however, no surviving copy could be found. In Haarlem and Leiden the authorities were alarmed by his activities, while their colleagues in The Hague and Delft showed no serious concern.

Haarlem

In Haarlem, Velsius was taken to the former mayor, Gerrit van Ravensbergen, because he had claimed that he could cure the old man's blindness. Velsius claimed that he could not do this by using drugs, but by a miracle that would prove that he, Velsius, was indeed God's messenger. When a miracle failed, the Prophet blamed his patient, who admitted that he had never really believed that such a miraculous cure could be effective.

Suffer

In September 1577, Velsius was in Leiden. In one church he climbed onto a pew from where he began to preach, which apparently attracted a sizeable audience. He announced that he would return the next day to give another sermon. The city magistrate prevented this and ordered him to leave the city. In a letter to the city council, Velsius stated that the judges had betrayed God and Christ by preventing him from spreading the word of God and leading the sheep into the correct flock, and that they had shown that they were tools of the Be devil and allow satanic false teachers to lead the flock astray.

Velsius last years

After spending another two unsuccessful years in Holland, Velsius, who must have been about seventy or more at the time, returned to Groningen, which at that time was still loyal to the king. In 1581 the authorities there decided to support the wandering prophet with a small but regular financial donation, which is also the last trace he has documented. It is believed that he died not much later.

Works (selection)

- 1541 Hippocratis Coi de insomniis liber. OCLC 560648916

- 1542 Ciceronis Academicarvm Qvaestionvm Liber Primvs Marcus Tullius Cicero; Justus Velsius: Ciceronis Academicarvm Qvaestionvm Liber Primvs. 1542, accessed March 10, 2020 (Latin). OCLC 615546903

- 1543 Vtrvm In Medico Varia-rvm Artivm Ac Scien-tiarum cognitio requiratur. OCLC 249273879

- 1544 De mathematicarum disciplinarum vario usu oratio. OCLC 165927235

- 1545 Procli de motu Libri II. OCLC 165353999

- 1551 In Cebetis Thebani Tabvlam Commentariorvm Libri Sex. OCLC 162385406

- 1551 Simplicii [Simplikios] omnium Aristotelis interpretum praestantissimi. OCLC 504390751

- 1551 In Aristotelis de virtutibus librum Commentarium libri III. OCLC 165670768

- 1554 De artium liberalium et Philosophiae Praecepta tradendi recta ratione. OCLC 165927237

- 1554 Probabiliter disserendi ratio et via quae in Aristotelis Topicis traditur. OCLC 458457289

- 1554 Κρισις [crisis]: Verae Christianaeqve Philosophiae comprobatoris. OCLC 311930648

- 1554 Description of the praising defender and successor of the Christian wisdom .... OCLC 254204811

- 1554 De humanae vitae recta ratione ac via, seu de hominis Beatitudinibus. OCLC 311881180

- 1556 Apologia Iusti Velsii Hagani, contra haereticae pravitatis appellatos Inquisitores. OCLC 67051278

- 1557 Tabula totius philosophiae moralis thesaurum complectens OCLC 457368255

literature

- Heinricus Pantaleon: Prosopographiae heroum atque illustrium uirorum totius Germaniæ , 1565 (Latin). OCLC 79416230

- Pieter Christiaenszoon Bor: Oorsprongk, begin, en vervolgh der Nederlandsche oorlogen, beroerten, en borgelyke oneenigheden , Amsterdam 1587, p. 21 ff. (Dutch). OCLC 249050708

- Hermann Joseph Hartzheim : Bibliotheca Coloniensis; in qua vita et libri typo vulgati et manuscripti recensentur omnium Archi-dioeceseos Coloniensis , 1747, p. 212 f. (Latin). OCLC 222764557

- Christian Sepp: Kerkhistorische studiën, Justus Velsius, Haganus , 1885, Leiden, EJ Brill, pp. 91–179, (Dutch). OCLC 13389121

- Frederik Lodewijk Rutgers: Calvijns invloed op de reformatie in de Nederlanden: voor zooveel die door hemzelven is uitgeoefend , Leiden 1901, p. 75 ff., ISBN 90-70010-98-4 , (Dutch). OCLC 9239220

- Jaques Pollet: XXV: Justus Velsius, Martin Bucer: études sur les relations de Bucer avec les Pays-Bas , EJ Brill, Leiden 1985, pp. 321-344, ISBN 90-70010-98-4 , (French). OCLC 401444765

- Klaus-Bernward Springer: Velsius (Velsen, Welsens), Justus , In Bautz Traugott (ed), Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) , Nordhausen: Bautz, pp. 1492–1495, ISBN 3-88309-091-3 .

Web links

- Velsius, Justus, 1510–1581 in Early Modern Letters Online (English)

- Velsius, Justus in CERL Thesaurus Humanist, theologian and medical practitioner; Reformation preacher, Prof. u. a. Löwen and Cologne, later in the Netherlands

- Velsius, Justus (1510–1581) in Identifiants et Référentiels (French)

- Velsius, Justus in Marburg professor catalog online

- Velsius, Justus in Open mlol (Italian)

- Velsius Justus in German biography

- Literature by and with Justus Velsius in Gateway-Bayern.de

- Literature by Justus Velsius in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

- Justus Velsius Haganus: An Erudite but Rambling Prophet Exile and Religious Identity, 1500–1800, In: cambridge.org

- Justus Velsius in the German Digital Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ De Wal suggested that Velsius could not come from The Hague but from Heeg in Friesland .

- ↑ a b Justus Velsius philologist, sources and research on the history of the Reformation, Gustav Adolf Benrath (ed.), Volume 54, sources on the history of the Baptist XVI, 1988, Gütersloh publishing Gerd Mohn in the Google Book Search

- ↑ Christiani Hominis Norma, General Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste in alphabetical order, edited by the authors mentioned and edited by JC Ed and JG Gruber, First Section AG, Leipzig 1871 in the Google book search

- ↑ Beatrix van Steenhoven, Exile and Religious Identity, 1500–1800, Edited by Jesse Spohnholz and by Gary K Waite, Number 18, First Published 2014 by Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) limited, ISBN 978-1-84893-457-3 in the google book search

- ↑ De mathematicarum disciplinarum vario usu oratio, by Justus Velsius, Verlag Argentoratum, 1544

- ↑ De mathematicarum disciplinarum vario usu dignitateque, by Justus Velsius, 1544, S, 5 (Latin)

- ↑ Proclus's De Motu Velsius, Writing the History of Mathematics: Its Historical Development, edited by Joseph W. staves, Christoph J. Scriba, Edited on behalf of the International Commission on the History of Mathematics, Birkhauser Verlag, Basel - Boston - Berlin 2002 , ISBN 3-7643-6166-2 in the Google book search

- ^ Georgij Trapezontij dialectica haec continens. On. MDVIIII. in Google Book Search

- ↑ George of Trebizond: a biography and a study of his rhetoric and logic, von Monfasani, John, 1976, p. 336 (English)

- ^ Proclus's De Motu (Elements of Physics) Velsius, Storia E Letteratura, Raccolta Di Studi E Testi, Paul Oskar Kristeller, Studies In Renaissance Thought and Letters, Vol. IV, Roma 1996 in the Google book search

- ^ German legal dictionary (DRW), Pagamentsgulden, In: Uni-Heidelberg

- ↑ Justus Velsius, Jost Welsens de la Haye, In: gropperforschung.villa-anemone.fr

- ↑ a b c d The Marzelle Gymnasium in Cologne 1450–1911: Pictures from its history: Festschrift, The Gymnasium on the occasion of its relocation, Dedicated by the former students, Edited by Professor Dr. Jos. Klinkenberg, 1911, pp. 22-36, In: Archive.org

- ^ The Anabaptists in the Duchy of Jülich Studies on the History of the Reformation, especially on the Lower Rhine, by Karl Rembert, 1899, p. 460

- ↑ Thomas von Imbroich, by Christian Neff (author), 1958 (English)

- ↑ Justus Velsius, Reformation History Studies and Texts, founded by Joseph Greving booklet 86, The late Ersamus and the Reformation, by Karl Heinz Oerlich, Aschendorff, Münster Westphalia 1961 in the Google book search

- ↑ Krisis: Verae Christianaeqve Philosophiae comprobatoris atq [ue aemuli, & Sophistae quiq́ [ue] Antichristi doctrinam sequitur, per contentionem comparationemq́ [ue] descriptio ..., by Justus Velsius, Coloniae 1554 (Latin)]

- ↑ Modern history of the city of Cologne, mostly from the sources of the city archive, by Dr. L. Ennen, city archivist, fourth volume, Cologne and Neuss 1875 in the Google book search

- ↑ JV Epistola ad Ferdinandum Romanorum Regem, Principes Electores, by Justus Velsius, 1554 (Latin)

- ↑ a b c Modern history of the city of Cologne, mostly from the sources of the city archive, by Dr. L. Ennen, city archivist, fourth volume, Cologne and Neuss 1875 in the Google book search

- ↑ Epistolae, aliaque quaedam scripta, et vocationis sue̜ rationem, et totius Coloniensis negotij summam complectentia ..., by Justus Velsius, 1557 in the Google book search

- ↑ Slotan, Johann: D. Ioannis Slotani Geffensis Sacrae Theologiae Professoris, Et Inquisitoris haereticae prauitatis Dispvtationvm Adversus haereticos Liber unus ..., by Johann Slotan, Coloniae 1558 (Latin)

- ↑ Marian exiles were English Protestants who fled to the continent during the reign of the Catholic Queen Maria I (Mary Tudor), i.e. between 1554 and 1558. They mainly settled in Protestant countries such as the Netherlands, Switzerland and some German states.

- ^ John Calvin: Selections from His Writings . Edited and with an Introduction by John Dillenberger. Ed .: John Dillenberger (= The American Academy of Religion [Hrsg.]: American Academy of Religion aids for the study of religion . Volume 2 ). Scholars Press, 1975, ISBN 0-9130-025-2 ( defective ) , LCCN 75-026875 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed March 29, 2020]).

- ↑ Letter from Johannes Calvin to Philipp Melanchthon of September 17, 1556, Corpus Reformation Volume XLIV., Ioannis Calvini, Opera Quae Supersunt Omnia, Brunsvigae, M. Bruhn, 1877, p. 280 ff., In: yumpu.com (Latin) (accessed on April 17, 2020)

- ^ EJ Brill: Nederlanders, students te Heidelberg. EJ Brill, 1886, accessed March 6, 2020 (Dutch).

- ↑ a b c The share of the Strasbourgers in the Reformation in Churpfalz; three writings with a historical introduction and on the occasion of the Reformation celebration in the Grand Duchy of Baden, by Johann Marbach (1521–1581), Charles Schmidt (1812–1895), Verlag CF Schmidt, Strasbourg 1856, p. XL f., In: Archive.org

- ^ Büttinghausen, Karl: C. Büttinghausen's contributions to the history of the Palatinate, Mannheim, 1776, In: bsb-muenchen

- ↑ Summa Christian doctrine and life Velsius, Franckfurtische Religions-Actions, which between a high-noble and high-wise magistrate and the Reformed burgers and residents there, because of the Exercitii Religionis Reformatae Publici, Frankfurt am Mayn, sought within the ring mudslides of this city Franz Barrentrapp, printed in Diehlische Buchdruckerey. MDCCXXXV. in Google Book Search

- ↑ Archive for Frankfurt's history and art, Frankfurter Verein für Geschichte und Landeskunde, Verein für Geschichte und Altertumskunde in Frankfurt am Main (1858), issue 5-8, second volume, Frankfurt am Main, Verlag von Heinrich Keller, p. 79 f. in Google Book Search

- ↑ a b c The History of the Life and Acts of the Most Reverend Father in God, Edmund Grindal, the First, by John Stripe, Clarendon Press 1821, pp. 135-138, In: Archive.org (English)

- ^ The Low Countries. Jaargang 2 (1994–1995), The Dutch Church in London Past and Present, In: dbnl.org (English)

- ↑ The Dutch Church, In: historicengland.org.uk (English)

- ↑ Justus Velsius London in 1563, Dutch Calvinists in Early Stuart London, The Dutch Church, Austin Friars from 1603 to 1642, Ole Peter Grell, EJ Brill, Leiden - New York - København- Cologne 1989, ISBN 90-04-08955-1 in the google book search

- ↑ a b Nikolaus Carinaeus, church order and discipline, Johannes a LASCO church order for London (1555) and the denomination refomierte Education, by Dr. Judith Becker, Brill, Leiden - Boston 2007, ISBN 978-90-04-15784-2, pp. 272 f. in Google Book Search

- ↑ Christiani Hominis Norma Velsius, Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reigns of Edward VI., Mary, Elizabeth, 1547-1580, Preserved in the State Paper Department of Her Majesty's Public Record Office. Edited by Robert Lemon, Esq. FSA, London 1856 in Google Book search

- ↑ illuminations a coelo velsius, The Remains of Edmund Grindal, DD Successively Bishop of London and Archbishop of York and Canterbury. Edited for The Parker Society, by the Rev. William Nicholson, AM, Cambridge: M.DCCC.XLIII. by Parker Society, London in Google Book Search

- ↑ a b c d e f g Justus Velsius Groningen, Exile and Religious Identity, 1500–1800, Edited by Jesse Spohnholz and by Gary K Waite, Number 18, First Published 2014 by Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) limited, ISBN 978-1 -84893-457-3 in Google Book Search

- ↑ Hippocratis Coi de insomniis liber. Claudij Galeni Pergameni de ea quæ ex insomniis habetur affectionum dignotione. IVSTO VELSIO HAGANO, Medico Antuerpiensi interprete. Antverpiae 1541 in Google Book search

- ↑ Vtrvm In Medico Varia-rvm Artivm Ac Scien-tiarum cognitio requiratur, by Justus Velsius, In: Johannes A Lasco Library Emden (Latin)

- ↑ De mathematicarum disciplinarum vario usu oratio, Argentorati, by Justus Velsius, In: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Latin)

- ^ Proclus <Diadochus> / Velsius, Justus: Proklu Diadochu peri kinēseōs biblia 2, Basilea, 1545, 105 S. In: Münchner Digitisierungs-Zentrum Digitale Bibliothek (PDF)

- ↑ Ivsti Velsii Hagani, In Cebetis Thebani Tabvlam Commentariorvm Libri Sex, Totivs Moralis Philosophiae Thesavrvs, by Justus Velsius, Lvgdvni, 1551 in the Google book search

- ↑ Simplicii omnium Aristotelis interpretum praestantissimi, Verlag Basileæ 1551 in the Google book search

- ↑ of Velsius, Justus: Just Velsii in Aristotelis librum de virtutibus Commentarium libri III, Coloniae, 1551. In: Munich Digitization Center Digital Library

- ↑ Velsius, Justus: De artium liberalium et Philosophiae Praecepta tradendi recta ratione, Colonia, 1554, In: Munich Digitization Center Digital Library

- ↑ Probabiliter disserendi ratio et via quae in Aristotelis topicis traditur, Justus Velsius, haer A. Byrckmann, 1554 in the Google Book Search

- ↑ De humanae uitae Recta Ratione ac uia, seu de hominis Beatitudinibus: Liber unus, 99 p. In the Google book search

- ↑ Apologia Iusti Velsii Hagani, contra haereticae pravitatis appellatos Inquisitores, by Justus Velsius in the Google book search

- ↑ Prosopographiae heroum atque illustrium uirorum totius Germaniae pars prima [-tertia , by Heinricus Pantaleon, anno 1565 (PDF), (Latin)]

- ↑ Oorsprongk, begin, en vervolgh der Nederlandsche oorlogen, beroerten, en borgelyke oneenigheden, 1587, by Pieter Christiaenszoon Bor in the Google book search

- ^ Bibliotheca Coloniensis, by Josephus Hartzheim in the Google book search

- ↑ Kerkhistorische studiën, by Christiaan Sepp, EJ Brill (Dutch)

- ↑ Calvijns invloed op de reformatie in de Nederlanden: voor zooveel die door hemzelven is uitgeoefend, by Frederik Lodewijk Rutgers, D. Donner, 1901, 250 p. In the Google book search

- ↑ Martin Bucer Tome I, Êtudes, Studies in Medieval and Reformation Thought, Leiden, EJ Brill 1985 in the Google book search

- ↑ VELSIUS (Velsen, Welsens), Justus, versatile humanist, by Klaus-Bernward Springer, author, In: Biographic-bibliographic church encyclopedia

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Velsius, Justus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Welsens, Joost; Velsius, Justus; Vels, Justus; Velserus, Justus; Velsius, Jodocus; Welsens, Justus; Velsus, Justus; Velsen, Josse |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Dutch humanist, physician and philologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1510 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | The hague |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 1581 |