Celtic princess grave of Reinheim

The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim is located in the Reinheim district of the Saarland community of Gersheim , in the Bliesbruck-Reinheim settlement chamber . It is a barrow with a circular moat . The grave is on the site of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim . The buried woman was an adult woman who belonged to the social elite and who also held religious and cultic duties as a priestess, healer or seer.

This was discovered around 370 BC. Dated and richly furnished grave in 1954 when sand was extracted in a sand and gravel pit . At that time, the gravel pit lay on a bump in the ground popularly known as a cat's hump. The princess grave was excavated and the finds were recovered between March 3 and 6, 1954. Further excavations took place between 1955 and 1957.

Between 1996 and 1999 the grave mound of the princess grave as well as the two grave mounds of the other graves found in the excavations from 1955 to 1957 were reconstructed about 100 meters from the actual site on a 1: 1 scale. The reconstructed princess grave mound is accessible. Replicas of all the important finds from the grave are exhibited inside . In addition, the actual burial chamber has been completely reconstructed.

In archeology, as in connection with the grave of Reinheim, the term princely grave is often used for this type of magnificent grave. Although it has historically been proven that there was a rich, socially superior Celtic leadership class, it is not known how the Celts themselves called the members of this class and what position they exactly held within the community. The terms " ceremonial grave" or " elite grave" are more appropriate today . The term princely grave is to be seen as a designation of a certain category of graves and not as an indication that the buried there were princes according to today's understanding.

Location

The grave was found on the elevation popularly known as the Katzenbuckel . (In the preliminary report, the place where the burial mound was found was incorrectly stated as the Heidenhübel instead of Katzenbuckel . This statement was corrected in the excavation report from 1965.) The Katzenbuckel is an approximately 2 meter high bump with a diameter of approximately 120 meters. It is located in the Bliesbruck-Reinheim settlement chamber, which extends from the German municipality of Gersheim-Reinheim to the French municipality of Bliesbruck . Through archaeological finds himself an unbroken history of settlement leaves from the late Bronze Age (13th century BC v..) To the older Merovingian (n. Chr 7th century.) Demonstrate. This space continuity continued especially during the Roman settlement, which is shown by the vicus built there , which had around 2000 inhabitants. A special social position is to be assigned to the owners of the Roman villa . This is not only supported by the area of the villa of approx. 2,550 m 2 , which included a farm yard with 13 outbuildings and an area of more than 44,000 m 2 , but also the parade mask found in the villa and a statue of the goddess Fortuna . This and the location of the villa in the immediate vicinity of the burial mound of the necropolis with the princess' grave and the right to settle outside the vicus could be an indication of a possible legal succession of the owners of the villa in relation to the Celtic ruling class.

Find history

In the 1950s, the entrepreneur Johann Schiel ran a sand pit on the Katzenbuckels site . When it was dismantled, it had come across a human skull and a bronze ring as early as 1952. He reported the find to the State Conservatory Office in Saarbrücken on April 19, 1952 via the Reinheim mayor's office. During the investigation initiated by the then state curator Josef Keller, further parts of the skeleton and the upper parts of a bowl were found. An anthropological study showed that the burial must have been a man between 45 and 55 years old. Since the sand mining had already progressed beyond the place of discovery, the grave was already destroyed by this time. No further finds could be made. The area was also not investigated further, although it had already been suspected that there might be other graves in the vicinity. The grave is referred to as grave B in the excavation report of 1965 by Keller.

In mid-February 1954, Schiel reported another find to the State Conservatory Office. While digging the sand by hand with a shovel, he had come across a small bronze figure and bronze fragments. He sent the bronze figure to the conservator's office. He covered the other fragments with sand again and stopped mining at this point. Inspection of the figure showed that it was the handle of a bronze mirror. The first on-site investigation took place on February 18, 1954. It revealed that Schiel had destroyed the mirror with the shovel during dismantling. After initial cleaning, a vertical black stripe in the sand was found in the sand that was extracted by hand, which indicated a wooden burial chamber. However, the burial chamber had already been partially excavated by the sand mining. Schiel assured that no finds had been made by then, but it cannot be completely ruled out that parts were lost during dismantling. The excavation itself began on March 3, 1954, as the frozen ground had not previously allowed it. Since the excavations had become public in the meantime and many onlookers had gathered on the site, the grave was guarded by officers of the gendarmerie from the evening of March 5, 1954 until the end of the excavation on the evening of March 6, 1954 to protect against theft .

In the preliminary excavation report from 1955, Josef Keller already suspected that the Katzenbuckel could be the remains of a monumental grave mound that had been leveled by agriculture over the centuries. The further excavations up to 1957 then showed that the Katzenbuckel represented the remainder of at least three monumental grave mounds, which was mainly leveled by agricultural use of the area . On the basis of other finds in the area that do not belong to any of the three graves, a fourth burial mound can be postulated , but this could not be proven.

Finding

A larger area was marked out above the presumed burial chamber. Subsequently, the soil began to be removed in layers from above. After the topsoil had been removed , the ground plan of the burial chamber emerged as 3 cm wide dark stripes in the ground at a depth of 1.62 meters. It was found that only the wall on the east side of the burial chamber was completely preserved. The west wall was completely destroyed and the south and north walls partially destroyed by the sand mining. The still completely preserved east wall was 3.48 meters long. The south side was 2.03 meters long and the north side was 2.70 meters long. As a result, the actual size of the burial chamber could no longer be determined. The burial chamber was excavated to a depth of 2.18 meters between the former wooden walls. The wood of the walls was completely gone and only survived as a black-brown layer, but in the lower area of the walls of the burial chamber the structure of two boards each approx. 30 cm high was clearly visible in this layer . Even the structure of the wood was still clearly visible here. Based on the discoloration in the sand above these structures, a third board with the same height can be assumed. A similarly dark discoloration of the floor of the grave also suggests a wooden floor. Likewise, a ceiling made of floorboards can be assumed. In the corners and on the edges of the grave the dark layer was thicker than on the side walls. This indicates that it was the beam structure that the side walls were attached to and that the ceiling rested on. An analysis at the Saarland University showed that it was probably oak .

Since at the time of the burial the layer of earth was 1.70 meters deeper at this point, the floor of the burial chamber must have been approx. 50 cm below the original level at that time. When the grave was laid out, a correspondingly deep pit, which reached down to the gravelly sand, must have been dug into which the wooden structure of the burial chamber was built. No bones were found from the burial. These had been completely dissolved by the silica-containing earth. The fact that the body was buried in the grave with the head facing NNW and the feet facing SSE, lying on its back, with slightly bent arms and hands on the stomach area, results from the location of the jewelry found.

Organic material adhering to the underside of a bowl (between remains of linen and a wooden fragment of the floor) and to the overturned bronze jug indicate a mat made of reeds or bast with which the floor of the burial chamber was covered.

After the Katzenbuckel had been measured by the St. Ingbert District Building Authority in 1955 and the plan was available in mid-June, a 95 meter long and up to 2.9 meter high profile of the Katzenbuckel was created. The basis was the 83 meter long east wall of the sand pit, which had been cleaned clean. The profile showed that a mound of earth had been piled up over the princess grave and that the grave mound had a circular moat. Since large parts of the circular trench had already been destroyed by the sand mining, it is no longer possible to say whether it was an open or a closed circular trench. The circular moat of the princess grave had a diameter of 20 meters, a depth of 0.4 meters and a width of 0.6 meters. The circular moat was about 1.5 meters inside the burial mound. This fact can be explained by the fact that parts of the burial mound have slipped on the sides and superimposed the circular moat. Based on the measurement data, the grave mound has a height of approx. 4.7 meters. The diameter was about 19 meters. No subsequent burials were found.

An extension of the profile by 12.50 meters then showed that a large burial mound had also been piled up above grave B, which was found in 1952. At the time of the discovery in 1952, the grave itself had largely been destroyed by sand mining, and the few finds (ring and shards of a vessel) raise the question of whether it was actually complete. Since no map of the Katzenbuckel was available at this point in time , its exact location is not documented. It is therefore unclear whether it was actually the central burial of the burial mound or a subsequent burial. For grave B, whose circular moat had a diameter of 22 meters and a width of 0.55 meters and which directly adjoined the burial mound, the result was a diameter of approx. 22 meters and a height of approx. 4.4 meters.

In the course of further excavations, the remains of another burial mound (grave C) were found. Only a small remnant of this burial mound could be detected in profile. There were three pieces of bronze and pieces of bone from an animal. Furthermore, human bones were found in three places and in a fourth place the remains of a cremation grave , which could be used for dating in the 1990s. However, all of these burials were reburials. The central grave and all other parts of the burial mound had already been destroyed by the sand pit at this time. This grave mound was east of the princess grave and grave B and was much larger than the two grave mounds. In addition, other finds were made in the area that could not be assigned to any of the three graves and must have belonged to a fourth burial mound, which could no longer be proven.

Finds

The following information on the distances of the individual finds, as far as stated, comes from the handwritten sketch of the measurements of the findings from the files of the State Conservatory Office Saarbrücken. On the neck are buried wearing a of gold produced torc . An elongated disc brooch was found in the middle of the chest . In the area of the left breast was a bronze mask brooch . On the right side, at the level of the forearm, was a gold bracelet and in the stomach area, where the right hand can be accepted, there were two gold finger rings. On the left side in the area of the arm in the lower area there was a gold arm ring, followed by a glass arm ring a little higher on top and an oil shale arm ring . A few centimeters below the right hand, about level with the hip, was an animal brooch depicting a rooster. On the right, at about chest level, was the hand mirror.

Directly on the east wall of the grave, 1.23 meters from the south wall, a gold-plated bronze jug with a lid with an opening facing north was found. The bronze jug was partially dented and broken into several pieces. 1.77 meters from the south wall and at a distance of 0.51 meters from the east wall was a bronze bowl with a diameter of 27.3 cm and directly above, 0.50 meters from the east wall, a bronze bowl with a diameter of 28 cm. To the left of the bronze jug, 1.29 meters from the south wall and 0.405 meters from the east wall, there was a gold cuff-shaped fitting . A second, similar fitting was located 1.13 meters and 0.615 meters from the east wall. A round disc brooch made of gold was located 0.66 meters from the south wall and 1.7 meters from the east wall. Next to the head of the dead was a complex of finds made of glass beads , amber beads , individual parts of a rod link chain, pendants and other finds. The finds were partially on top of each other. The find complex was oval in shape. It measured 0.35 meters in east-west direction, 0.5 meters in north-south direction and was 0.625 meters away from the north wall. Its center point was about 1.7 meters from the east wall. Due to the arrangement of the individual pieces of the find complex, some of which were on top of each other and all found in a limited area, it can be postulated that the objects were in a container. What kind of container it was cannot be said. However, it must have consisted of an ephemeral material, as no traces of it were found. Most likely, a wooden box will appear . Tissue and wood residues adhered to some of the finds.

The outstanding finds from the Reinheim grave include the gold jewelry consisting of the torque, two arm rings and a gold-plated bronze jug. In particular, the bangle and the torc, which bear the representation of an unknown female deity at their ends and have models in the Greek and Etruscan regions, are to be emphasized here. The bronze jug included two bronze bowls. Due to the two golden, cuff-shaped decorations found, two drinking horns can be postulated as associated drinking vessels . The multiple assumption that the bronze jug and the associated dishes were on a small table would mean that the burial chamber would have to be higher, as can be proven by the wood traces on the outer walls. Traces of a fourth board should have been found here. Other finds to be emphasized are the two disc brooches made of gold with coral trimmings, the mask fibula depicting a leopard's head and a human head, and the animal fibula in the shape of a rooster with coral trimmings and legs .

The animal fibula next to the pelvis and the mask fibula in the area of the left breast are to be regarded as fasteners for two items of clothing that the deceased was wearing at the time of burial. What is certain is that it must have been two separate pieces of clothing. Such a type of combination of fibulae for closing clothing has so far only rarely and predominantly been found in Switzerland . The elongated disc fibula found at the level of the neck and the round disc fibula found at the feet of the dead, which Keller assumes in the excavation report, "[...] that it was attached to a dress that was at this point." with the location of disc fibulae in other graves, in which these were found not only in the neck area, but also next to the head and below the feet, as closures of a shroud. Based on current knowledge, it is not possible to draw any conclusions about the social status of the dead on the basis of any special clothing that is rarely observed. However, the primers show that it was a woman.

The finds are now in the Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Saarbrücken.

The following table lists all finds from the Keller find catalog. The descriptions have been supplemented accordingly with the latest findings.

| Finds of the princess grave from the find catalog of Josef Keller (with the addition of new findings) | ||||||

| category | object | material | description | number | Find catalog number | photos |

| Finger rings, arm and neck rings, pendants, fibulae | Torques | gold | Driven and forged. Hollow. Composed of at least 25 individual parts. Outside diameter 172 mm, inside 153 mm. Weight 187.2 g. At the ends two human heads, wearing a helmet designed as the head of a bird of prey. Behind the heads are two heads of big cats in relief. | 1 | Cellar No. 1 | |

| Bangle | gold | Smooth, hollow oval bangle. Details of the surface chiselled , punched and engraved . In the casting process produced. Assembled from several parts. Outside diameter 80.5 mm, inside 61 mm. Weight 117.1 g. A figurative representation with a head and chest area at both ends. On the head bird-like jewelry and a helmet in the shape of a bird of prey. Wings on the shoulders. The hands held in front of the chest hold an unidentifiable object. Representation of the hair and a dress. Above the heads, looking outwards, the depiction of two big cats, whose whiskers can be seen as punched points. The figurative representation combines attributes of the goddesses Artemis and Minerva . | 1 | Cellar No. 2 |

|

|

| Arm ring | gold | Outside diameter 67.7 mm, inside 54.7 mm. Weight 29.6 g. Snap closure. Decorated with ornaments . Probably from the same workshop as the Torques. | 1 | Cellar No. 3 |

|

|

| pen | gold | Length 7.4 mm. Diameter 1.4 mm. Weight 0.15 g. Belongs to the gold bracelet and was used for the clasp. | 1 | Cellar No. 4 | ||

| Finger ring | gold | Outside diameter 21.3 mm, inside 18.7 mm. Width 10.5 mm. Weight 7.7 g. Consists of three rings between which a twisted, twisted and looped square wire is soldered. Probably made according to the Etruscan or Greek model. Instead of the usual round wire, a square wire like the one found on a trailer in Switzerland was used. | 1 | Cellar No. 5 |

|

|

| Finger ring | gold | Outside diameter 20 mm, inside 18.2 mm. Weight 1.7 g. Made from a simple sheet of gold strip 2 mm wide. | 1 | Cellar No. 6 |

|

|

| Elongated disc brooch | Iron, gold and coral | Length 37.5 mm. Width 25 mm. Bracket and holding plate of the gold sheet made of iron. Rosette-shaped , lyre-shaped upwards. With embossed and punched decoration on the gold sheet. There was probably a large coral bead in the middle. Around it a wreath with decoration, around which a circle with 13 wells is arranged. These were alternately set with a coral pearl. To the lyre-shaped extension with two coral pearls. At the end of the extension there were three coral pearls. The inner pearl was no longer preserved. A single leaf is depicted above the center bead. Of the seven pearls of the circle and the three pearls of the appendix, only one was left. The beads were attached with a pin passed through them. The diameter of the pearls of the circle and the extension is 3 mm. | 1 | Cellar No. 10 |

|

|

| Round disc brooch | Iron, gold and coral | Bracket and holding plate of the gold sheet made of iron. Sheet gold made of an inner solid disc (diameter 26.7 mm) and an outer ring disc (outer diameter 41 mm, inner 24 mm). Gold sheet with decorations. In the middle a single coral bead. Several ornaments arranged in a circle around it. Around it 20 coral beads with a diameter of 4.6 mm are arranged in a circle. The beads were attached with a pin passed through them. Remnants of tissue clinging to it. | 1 | Cellar No. 11 and No. 202 |

|

|

| Mask brooch | bronze | Incomplete. Groove for decorative strips. With a representation of a leopard and a human head touching on the chin. | 1 | Cellar No. 13 | ||

| ring | bronze | Diameter 85 mm. Cross section 4 mm. Adhered to the fabric under the mirror. | 1 | Cellar No. 16 and No. 201 | ||

| pendant | bronze | Length 64.6 mm. Left foot is missing. Fully plastic representation of a naked man with legs slightly apart and depicting the male sex. The head and the raised hands hold the pendant ring. | 1 | Cellar No. 19 | ||

| pendant | bronze | Length 53.2 mm. Fully plastic representation of a naked man with slightly buckled legs and depicting the male sex. Ring eyelet on the head. Hands bent in front of the chest. | 1 | Cellar number 20 | ||

| Finger ring | bronze | Outside diameter 22 mm, inside 19.5 mm. Width 7.9 mm. Reconstructed from several fragments. Incomplete. Decorated with a fish-bubble-shaped pattern. | 1 | Cellar No. 21 | ||

| Ring | bronze | About 16 small rings with different diameters can be reconstructed from 42 bronze fragments found. The diameter of the rings is between 7 mm and 17 mm. | 16 | Cellar No. 22 | ||

| Animal primer | Bronze, coral and bone | Length 63.8 mm. Height 33.4 mm. Depiction of a rooster with plumage and tail feathers. Coil spring with four turns. On both sides of the spiral axis, pearls made of coral and bone were attached. The comb, eyes and base of the tail are each decorated with coral. A thin white thread adhered to the neck of the rooster and the needle. | 1 | Cellar No. 14 and No. 203 | ||

| Arm ring | Glass | Crystal clear with inclusions of small air bubbles. Outside diameter 81.7 mm to 84.5 mm, inside 64.7 mm to 66.6 mm. Thickness 8.1 mm to 8.8 mm. | 1 | Cellar No. 34 | ||

| ring | Glass | Light green, transparent. Outside diameter 28 mm to 29 mm, inside 14.5 mm to 14.7 mm. Thickness 4.6 mm. | 1 | Cellar number 51 | ||

| Arm ring | Oil shale | Outside diameter 108.3 mm to 109.7 mm, inside 81.4 mm to 82 mm. Thickness 15.8 mm to 16.7 mm. | 1 | Cellar number 54 | ||

| pendant | Quartzite | Black. Diameter 35 mm to 38.8 mm. Thickness 11.7 mm. Hole diameter 6.6 mm to 8.3 mm. Pebble with a natural hole. | 1 | Cellar number 56 | ||

| pendant | stone | Olive green. Length 25.4 mm. Widths 13 mm and 19.8 mm. Thickness 3.5 mm to 8 mm. Diameter drill hole 5 mm and 8.1 mm. Trapezoidal. Broadside thin. | 1 | Cellar No. 57 | ||

| Shoe tags | Amber | Length 30.1 mm. Height 26.1 mm. Width 8 mm. Diameter drill hole 2.3 mm. | 1 | Cellar number 66 | ||

| Rod link chain | Bar links | iron | Length between 36 mm and 45 mm. | 25th | Cellar no.25.1 to no.25.39, no.202, no.203 and no.206 | |

| Ring songs | iron | Diameter between 7.5 mm and 11.6 mm. Partly still connected. Tissue traces adhered to two sections. In addition, remains of a tube made of wood in which the remains of a 4 mm thick cord were found. | 111 | |||

| Stalked rings | iron | Length between 26 mm and 37.6 mm. Diameter between 14 mm and 17.3 mm. A ring with a curved stem. | 4th | Cellar No. 26 to 29 | ||

| Pearl necklace | Eye bead | Glass | Black. Diameter 37.2 mm to 38 mm. Hole diameter 10.5 mm to 11 mm. Axis 28 mm to 31 mm. In the middle of the circumference five humps which are framed by three circles in the colors white, yellow, and white. A hole mouth is surrounded by 11 eyes alternating in the colors yellow, yellow, white, yellow, white, yellow. The other opening with 10 eyes alternating in the colors white and yellow. | 1 | Cellar No. 35 | |

| Eye bead | Glass | Turquoise blue. Diameter 24 mm to 24.6 mm. Hole diameter 10.5 mm. Axis 20 mm. On one side four and on the other side three rounded fields of brown glass with white-blue eyes. | 1 | Cellar No. 36 | ||

| Eye bead | Glass | Greenish blue. Diameter 23.4 mm to 24.8 mm cm. Hole diameter 6.3 mm. Axis 21.2 mm. On one side four and on the other side three rounded fields of brown glass with white and blue eyes. | 1 | Cellar No. 37 | ||

| Pearls | Amber | Beads of various shapes and sizes. | 125 | Cellar No. 67 to 191 | ||

| Slider | Amber | Different sizes. Sometimes only fragments with up to five holes. | 5 | Cellar No. 192 to 196 | ||

| Decoration and accessories of drinking vessels | Cuff-shaped fitting | gold | Diameter above 45 mm to 47 mm, below 41 mm to 43 mm. Width 33 mm to 33.8 mm. Thickness 0.15 mm. Weight 4.1 g. With ornaments with a flower pattern, pearl rod and semicircular arches. With openings in the material. Presumably decoration of a drinking horn. | 1 | Cellar No. 7 |

|

| Cuff-shaped fitting | gold | Diameter above 45 mm to 47 mm, below 41 mm to 43 mm. Width 31 mm to 32.5 mm. Thickness 0.15 mm. Weight 3.4 g. With ornaments with a flower pattern, pearl rod and semicircular arches. With openings in the material. Presumably decoration of a drinking horn. | 1 | Cellar No. 8 | ||

| rosette | gold | Diameter 10 mm to 10.3 mm. Thickness 0.15 mm. Weight 0.4 g. Found on the cuff-shaped fittings. Probably parts of the accessories for the drinking horns. Possibly decoration of the lid or a strap. | 3 | Cellar No. 9 | ||

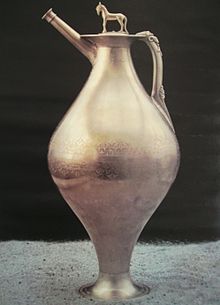

| Drinking service | Tubular jug | gilt bronze | Height with lid 514.2 mm. Diameter at the widest point 232 mm. On the lid a plastic figure of a horse with a human head. Male head with long goatee and hair combed back. Decoration of the jug with ornaments, relief depictions, in high relief depictions of men's heads. As well as a ram's head on the jug lid. Ornaments with a lotus flower pattern and a fish bubble pattern. Tartar residue was found on some parts. Tissue and wood residues sticking to the bottom of the jug. | 1 | Cellar No. 12, No. 202 and No. 206 |

|

| Donation bowl | bronze | Diameter 280 mm. Height 50 mm. Undecorated. A double-layered piece of white linen with 3 dark blue stripes in different patterns with the dimensions 219 mm × 173 mm adhering to the underside. A piece of wood with a length of 305 mm, a width of 285 mm and a thickness of 1 mm to 3 mm is lying on the plate. Including two wooden boards. | 1 | Cellar No. 17, No. 199 and No. 204 |

|

|

| Donation bowl | bronze | Diameter 273 mm cm. Height 412 mm cm. Undecorated. A piece of white linen with dark blue stripes with the dimensions 260 mm × 214 mm attached to the underside. Under the linen was an oval piece of wood with a length of 275 mm, a width of 210 mm and a thickness of 1 mm to 5 mm. The grain suggests a piece of oak wood on the floor. Between wood and linen, in the middle, single-fiber, litter-like fabric that can come from a bast or reed mat with the dimensions 160 mm × 100 mm. | 1 | Cellar No. 18, No. 200 and No. 205 | ||

| Other utensils | Hand mirror | Bronze and coral | Diameter of the mirror pane 189 mm. Thickness of the mirror pane 1.3 mm. The handle ends in a spout that is hollow at the end. Presumably a handle made of old material was attached here. Two-sided representation of an upper body with a Janus head towards the mirror surface . Arms bent upwards. The mirror surface was connected to the handle by the hands. Decoration of the palms with coral. Head framed by fish-bubble-shaped leaves. Under the mirror the remains of a fine tissue measuring 133 mm × 95 mm. Including a wood fragment from 5 mm to 10 mm. The grain suggests oak and probably comes from the floor of the burial chamber. | 1 | Cellar No. 15 and No. 201 |

|

| knife | iron | Length 72 mm (with mandrel), length blade 48 mm. Width of the blade 14.3 mm. Thickness 4 mm. Tip is missing. Back convexly curved. The thorn was still stuck in the wooden remains of the handle. | 1 | Cellar No. 23 and No. 206 | ||

| rifle | iron | Length (with lid bead) 55 mm. Bushing diameter 19.5 mm. Lid diameter 20 mm. There is an eyelet on the side of the floor. Several bronze and iron rings are corroded on the lid. Remnants of a string adhering to the can and the rings. The lid and can were so rusted together that it was not possible to open the can. | 1 | Cellar No. 22.3, No. 24 and No. 203 | ||

| Arrowhead | chalcedony | Length 32.2 mm. Width 19.3 mm. 8.4 mm thick. Neolithic to Eeolithic . Presumably used as an amulet . | 1 | Cellar No. 58 | ||

| Amber stick | Amber and silver | Length 88 mm. Thickness 18 mm. From five connected parts. At the end piece, silver chains with rattling amber beads. | 1 | Cellar # 198 | ||

| Others | Pearls | Glass | Different sizes and colors. All with a drill hole. | 14th | Cellar No. 38 to 50 | |

| Bullet | jasper | Brownish-yellow to black-brown-violet. Diameter 23.5 mm. Irregular surface. | 1 | Cellar number 59 | ||

| Bullet | Chert ? | Black-blue to brownish-gray. Diameter 15 mm. | 1 | Cellar number 60 | ||

| rivet | bronze | Length 4 mm. Head diameter 7 mm. Both were found in the animal primer. | 2 | Cellar No. 22.5 and 22.6 | ||

| Fragment of a petrified ammonite | Size 36.6mm × 11mm × 12mm. Covered with iron rust. Remnants of tissue adhered. | 1 | Cellar No. 61 and No. 202 | |||

| Flint chipping | Size 8.6mm × 11.4mm × 2.2mm. | 1 | Cellar No. 62 | |||

| Fragment | Red iron ore ? | Size 37.5mm × 25.7mm × 16.3mm and 14mm × 9mm × 8mm. | 2 | Cellar No. 63 | ||

| Fragments | Amber | Various fragments, shavings and splinters from sliders and beads. | 1 | Cellar No. 197 | ||

| Fragment of a ring | lignite | Length still 31 mm. Cross section 7 mm. | 1 | Cellar number 64 | ||

| Fragment | jet | 11 mm × 10 mm × 5.5 mm and 8.5 mm × 4.5 mm × 2.5 mm. | 2 | Cellar No. 65 | ||

| Fragments | bronze | All parts were found in the mask primer. An object could not be reconstructed. But they are not part of the mask primer. | 11 | Cellar No. 22.8 to 22.18 | ||

| ring | iron | 1 | Cellar No. 30 | |||

| Remnants of rings | iron | Adhering to an iron fragment. | Cellar No. 31 | |||

| Shapeless pieces | iron | Length 19.2 mm, 16.5 mm and 12.6 mm. | 3 | Cellar No. 32 | ||

| Fragments | iron | 75 | Cellar No. 33 | |||

| Fragments of finger ring | Glass | Light blue, transparent glass. | 2 | Cellar No. 52 | ||

| Fragment | Glass | clear glass. Size 4.8mm × 4.8mm × 5mm. | 1 | Cellar No. 53 | ||

| Fragment of a ring | Oil shale | Rectangular. Length 27.7 mm. Cross section 9.5 mm × 11.5 mm. | 1 | Cellar number 55 | ||

| Tissue remnants | linen | With the dimensions 130 mm × 40 mm, 75 mm × 35 mm and 9 mm × 8 mm. | 3 | Cellar # 202 | ||

| Wood scraps | Various small pieces of wood that stuck to various metal objects. | 40 | Cellar # 206 | |||

Remarks

- ↑ The manufacturing process originally assumed by Josef Keller in the description of the grave goods from 1965 has meanwhile been refuted by material-technical investigations.

- ↑ The manufacturing process originally assumed by Josef Keller in the description of the grave goods from 1965 has meanwhile been refuted by material-technical investigations and with it the assumption that both the torque and the arm ring were made by the same blacksmith.

- ↑ Keller addresses this primer with different names. In the excavation report from 1965 with gold leaf brooch and in the preliminary excavation report from 1955 with a decorative disk. In the description of the grave goods belonging to the excavation report from 1965, neither of the two names appears. A comparison of the photo of the decorative disc from the report from 1955 with the photo of the elongated disc brooch from the report from 1965 shows that this is actually the elongated disc brooch.

- ↑ In the description of the grave goods from 1965, Josef Keller states that the decorations were pressed. Studies have shown, however, that the decorations are embossed and hallmarked. In Germany, Austria, Switzerland and France only round disc brooches have been found so far. Only in Alphen aan den Rijn in the Netherlands has a comparable silver specimen been found so far.

- ↑ In the 1965 find catalog, the size of the figure is given as 66.7 mm. In addition, the two legs are glued on above the lower legs. Since Keller does not mention this break in his report and it cannot be traced back to the photos, it can be assumed that this break occurred more recently than after the discovery and cataloging. This explains the difference in the size information.

- ↑ In the preliminary excavation report from 1955, the material was given as lignite . An appraisal in 1956, however, showed that it is oil shale.

- ↑ In the description of the grave goods, the shape of the pendant is described as a foot. In fact, it can be addressed as a shoe trailer. This form of the trailer was widespread from the late Hallstatt period to the late Latène period.

- ↑ The rod link chain was only found in the individual parts above. A closure could not be found. Possibly the stalked ring with the curved handle had a function in this regard. The other rings could have been belt pendants. Based on the bar and ring links found, the original length of the chain can be assumed to be around 1.6 meters.

- ↑ The whole pearl necklace was not found. Only the amber beads, the sliders and the three eye beads, probably made in a Carthaginian workshop in the Mediterranean region, were found together in one place. The necklace is based on a reconstruction by B. Brugmann based on signs of wear.

- ↑ The assumption already expressed in the excavation report of 1965 that the jug contained wine has meanwhile been proven by the state, teaching and research institute of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate through an examination of the samples taken and secured by the Roman-Germanic Central Museum in Mainz become.

- ↑ a b Keller describes the bowls in the excavation report as plates. Cultural-historical considerations and comparisons with finds in other graves suggest, however, that it was donation bowls with which wine was offered to the gods before a meeting began. The remains of wood found in the bowls and the remains of tissue from cloths indicate that the bowls were originally covered with wooden boards and wrapped in cloths.

- ↑ The box was sawed open in the workshops of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum in Mainz and then glued back together. The examination showed that the can was empty

- ↑ In the description of the grave finds in the excavation report from 1965, the amber stick is listed as a "handle-like amber object with rattling pearls". With new x-rays, the rod could be reconstructed in a slightly different form. Comparisons with finds in Dürrenberg, Šmarjeta and Vinkov suggest that it was a cult staff.

Documentation and completeness of the find

The documentation of the excavation in 1954 and the excavation campaigns in 1955, 1956 and 1957 is not always complete and consistent. In 1954 there was no topographical map of the Katzenbuckel area . It was only commissioned after the finds had been recovered in 1954 and was available in mid-1955. This meant that the exact location of the burial chamber found in 1952 could no longer be precisely traced. The location of the grave chamber of the princess had to be projected into the present map based on a handwritten sketch drawn up in 1954 with distance information, as the sand mining continued after 1954 had destroyed the grave chamber and a new measurement was no longer possible.

The fact that the exact places where the grave goods were found were not all precisely measured can in most cases be compensated for by available photos. However, some finds are not shown on the measurement sketch. The fact that these are drawn in the final drawing of the excavation plan suggests that they were transferred to the excavation plan on the basis of the photographs. There are no other finds on the photos, nor are they drawn in on the excavation plan or the measurement sketch, which concerns above all the individual components of the find complex to the left of the head of the buried, but also the three golden rosettes. As a result, their exact location can no longer be traced. It can be assumed, however, that the objects in the multi-layered find complex were next to the head.

The exact course of the boundary between the still preserved burial chamber and the part of the grave that had already been destroyed by the sand mining was also not measured. The photographs taken do not provide precise information about their course either, as they were not taken vertically from above, but from above at an angle. This means that the course drawn in the excavation plan should only roughly coincide with the actual course. In the drawings of the subgrade and the profiles of the excavation from 1956, there are some inconsistencies with regard to the scales indicated on the drawings of the profiles. The handwritten scales do not match the enclosed meter scales.

Only in the unpublished excavation documentation does a dam appear, which was heaped up on the original ground level from gravelly sand and limestone, ran in a north-south direction and was recognizable as banding. However, no attention was paid to this banding in 1955. The dam was only noticed during the subsequent excavations in 1957. However, most of it had already been excavated by sand mining at this point. Since the main profile intersects this one more time, the assumption is that the grave was originally surrounded by a rectangular dam. Keller showed no interest in this observation. Because he was of the opinion "It is neither a matter of filling layers nor of superimposed lawn probes, but merely of a later and naturally created banding." He also showed no interest in the limestone in the section of the profile. For the limestones it was clear to him "[...] that their location was accidental and there was nothing remarkable behind it." What led him to make these assumptions remains unclear, as he is not further stated in the official excavation report or in the unpublished documentation expresses this issue.

The fact that some research results, with regard to the manufacture of some of the objects, by the workshops of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz led to partially incomplete or incorrect results and were included in Keller's 1965 find catalog together with partially resulting incorrect conclusions, are due to the fact that in In the 1950s, today's technical possibilities for examining the finds were not available. For example, the box found in the princess's grave had to be sawed open and glued back together to check its contents. This led to the fact that the rifle is approx. 0.6 mm smaller today than stated when it was found in 1954.

Despite the partially incomplete or inconsistent documentation of the finds and the excavation documents, the grave of the Princess of Reinheim is one of the best documented of its kind. The documentation allows the conclusion that, apart from the part of the grave chamber that was destroyed by the sand mining, is an undisturbed burial. The question of the completeness of the find cannot be answered conclusively, since it cannot be completely ruled out whether finds were not overlooked during sand mining and are therefore lost. In this regard, especially with regard to the excavated part of the burial chamber, Keller also notes in the excavation report from 1965: “That nothing should have been there at all disturbs the idea of the whole a little. How easily something can have been overlooked when extracting sand. "

Dating the grave

The dating of the grave has been the subject of various publications and discussions since its discovery. The main subjects of discussion here were the glass arm ring, the tubular jug, the arm rings and cultural-historical considerations. Stylistic and art historical considerations were made to date the grave of Reinheim. Comparisons were made with finds in other trenches and comparisons with imported Attic jugs, bowls and beakers as well as the paintings on Attic and Greek vases. Attic vase painting in particular is best dated. The figurative representations of the bracelet, the mask brooches and the torque were compared with it. According to this, the grave of Reinheim belongs to the time La Tène A level 3. (approx. 370 BC)

The buried

Determination of age and gender

Since no parts of the skeleton have been preserved, the age and sex cannot be determined by anthropological studies. Since the wearing of arm rings on both sides was never found in male burials, but only in female burials, it can be postulated as archaeologically proven that the burial was a woman. Based on the location of the jewelry found, a height of about 1.60 meters can be assumed. This and a comparison with the arm rings, which have a 2 cm smaller diameter than that of the girl buried in the Celtic children's double grave in the Celtic burial mound Horres who, according to the available anthropological report, was 12 to 14 years old at the time of death and one for his age was above average height shows that the dead woman was an adult woman.

Contemplation of the ritual of the dead

The grave was created away from the local cemetery. It lies in a small necropolis consisting of at least two other graves with burial mounds and was the last of the three graves. As was common in the early La Tène period, with a few exceptions in France and Italy, a burial mound was piled up over the grave. The grave also had a circular moat. The burial chamber, about halfway into the ground, was paneled with wood on the walls, floor and ceiling. Even if the majority of the half-sunk graves are graves of women, this does not allow any particular conclusions to be drawn about the position of the buried. In addition to the graves with burial chambers half set in the earth, there are also those with burial chambers completely set in the earth, as well as with burial chambers that were built on the ground and over which a burial mound was built. There was no stone packing over the burial chamber. This distinguishes the Reinheim grave from many of the princely graves of the early La Tène period. In principle, these stone packings could be interpreted as protection against grave robbers. However, this contradicts the fact that they were not present in all graves. In particular, there were no stone packings in some of the particularly richly decorated graves and in all of the graves in which chain links were found. Therefore, the stone packing is more of a cultic meaning. It probably served as a protection against the return of the dead. This, in turn, implies that those buried in graves without stone packs were dead that the population was not afraid of. The findings of the structure of the burial chamber, the location of the grave away from the local cemetery in a small necropolis and the presence of a burial mound with a circular moat, with the exception of the lack of a stone packing above the burial chamber, show the grave as a typical princely grave from the springtime atene.

The burial was, as is usually the case with princely graves in the early La Tène period, a funeral. The deceased was buried lying on her back in a north-south orientation with a small deviation to north-north-west and south-south-east. Since the majority of women's graves have such an orientation, the burial can also be addressed as female under this aspect. At the time of the burial, the deceased wore a richly decorated costume. Both on the body itself and on the clothing she was wearing at the time of the burial. The fact that the arm rings, the finger rings and the torques were made of gold can be taken as a sure sign that the woman belonged to a wealthy class of the population. The oil shale ring worn on the left upper arm, on the other hand , clearly shows the buried person as one to the other, as can be proven by comparative finds in other princely graves ( Dürrnberg , Kleinaspergle , Worms-Herrnsheim , legs “Les Commelles”, Murigny, Waldalgesheim , Courcelles-en-Montagne) Person belonging to the executive class. The glass arm ring could have served a similar function.

The drinking service, which consists of a jug, two drinking horns and two bowls, can be seen in this combination mainly as grave goods at male burials. These additions are very rare in women's graves. This circumstance indicates a special position of the dead. So the two bowls, which were not suitable for drinking from because of their shape alone, can be postulated as donation bowls. This is also indicated by the fact that the two bowls were covered with wooden boards and each wrapped in a cloth. Such a procedure cannot be observed for mundane eating utensils. Donation bowls were used to offer the first drink to a deity before the meeting began. An appraisal of the jug showed that there was wine in it at the time of the burial. Since the cultivation of wine in the early La Tène period was not yet widespread among the Celts and can only be proven in the Roman period, this wine was very likely imported, either from the Mediterranean region or from the Greek colony of Massalia in southern France . The import of wine and the information that it was drunk by the wealthy ruling class comes from a fragment of the histories of Poseidonios handed down by Athenaeus . The beverage service and the wine thus identify the dead von Reinheim as a member of the executive class.

A mirror was found on the right side of the dead. Mirror finds in the early La Tène period are extremely rare. With the mirror from Reinheim, only two other finds are documented for Central Europe ( Hochheim and Courcelles-en-Montagne) and therefore do not belong to the usual grave goods. The handle of the mirror depicts a Janus-headed human figure. Although anatomical references to gender are missing , the figure can be identified as female by the two rings engraved on the arms. The head of the figure is adorned by two fish bubbles, which give the portrayed woman sacred meaning. The mirror was made by a Celtic craftsman based on the Greek model. Pictures on Greek vases show that these metal mirrors were used as mantic cult instruments. This type of use can also be postulated for the mirror found in the princess grave. Part of the find ensemble consisted of amber and glass beads. The amber beads and the three eye beads made of glass belong to an amber necklace to be postulated. The ability of amber to become electrically charged when rubbed and thereby to attract or repel other materials was already known in antiquity and led to amber being ascribed magical powers. This shows the necklace as a regalia with a cultic-religious character, which was not worn as an everyday, profane piece of jewelry. While rod link chains were part of the costume in the late Hallstatt period, from the early La Tène period these can only be seen as grave goods, but only in a few women's graves with special grave goods that indicate a cultic-religious function of the buried. In addition, none of these graves have a stone packing over the burial chamber. Together with the rod link chains, just like the rod link chain in the grave of Reinheim, a large number of strange-looking pendants made of bronze and stone as well as glass and amber were found. Some finds in situ show that these were originally attached to the rod link chain . According to the findings, this applies at least to southern Germany from the early La Tène period. So it can be assumed that remnants of a cord for Reinheim, partly adhering to the rod members and some other finds, show that the figural pendants in particular, but probably also at least some of the glass beads, the perforated stones, the shoe pendants and the box on the Rod link chain were worn. Since the rod link chain is not to be regarded as part of the everyday costume, it shows as a regalia that was only worn on certain occasions. It is therefore also clear that the objects worn on it could not have had the function of protective amulets, but had a religious-cultic function. Because protective amulets only protect the wearer when they are worn. The various other predominantly mineral finds from the ensemble can also be seen as religious and cult objects. As passed down from many cultures of antiquity, specially shaped, colored stones or stones made from special materials were ascribed magical powers. Although there are no written sources that prove this for the early La Tène period, it can be assumed that this idea was also widespread among the Celts. Corresponding stones can be found in many graves up to the Champagne region as grave goods or worn on chains. The amber rod with the chains and the pompons attached to it are special in terms of the material and size chosen. All similar rods that have been found so far are made of different materials and are much larger. It is not possible to verify exactly what function these bars had in the Celts. Images on Italian and Greek vases, however, show women in the role of priestesses or seers who carry such wands while performing ritual acts, although the exact meaning remains unclear here as well. A transfer of this fact to the staff of Reinheim and thus its importance as a cult staff of a priestess or clairvoyant is possible in principle.

Social status

The large burial mound with a circular moat, which was located away from the local cemetery and the construction of which represented a not inconsiderable community effort by the population, the rich grave goods as well as the jewelry worn and the comparison with other princely graves show that the deceased belonged to the social leadership class, regardless of theirs religious status. This becomes clear when comparing it with other women's graves with rod link chains, which have a much simpler grave decoration made of bronze jewelry. In addition, eight burial mounds from Hallstatt and the Early and Middle La Tène periods have been found in the Almend and Auf dem Sand corridors near the Katzenbuckel necropolis . Likewise, the rich, to about 270 BC. Dated to the 4th century BC, the cremation grave of a woman found that contained the remains of a bronze rod link chain. This and other graves and remains of settlements found within sight allow the conclusion that Reinheim assumed a rich Celtic ruling class as a seat with extensive lands from the late Hallstatt period to the late Latène period and the beginning of Roman settlement, i.e. over a period of 500 years to which the woman buried in the princess' grave also belonged. The objects of the find ensemble next to the left head such as the rod link chain with the associated pendants and the amber necklace represent a regalia with a religious and cultic character. The minerals found are also to be regarded as magical objects. Together with the amber stick, which can be assumed to be a cult object, and the fact that all these objects of the dead were given to the grave, i.e. were their property, as well as the depiction of an unknown deity on the neck and arm ring, show that the dead woman was alive was permanently entrusted with religious and cultic tasks of a priestess, healer or clairvoyant.

Museum presentation of the burial mound

The facility was reconstructed between 1996 and 1999 with funds from the Saarpfalz district and was inaugurated on June 26, 1999. The place where the replicas of the three burial mounds are today is not where the graves were found. The original sites were about 100 meters further southeast. They are no longer available today because they were destroyed by the gravel and sand mining of the sand pit. The entrance to the princess’s burial mound is formed by a pavilion with an information stand with the cash desk where further literature can be purchased, various information boards and a video wall. From there, a staircase leading down, past other information boards, leads to the actual exhibition room of the burial mound. There are additional information boards on the walls, as well as showcases in which replicas of some of the finds are displayed. The center of the exhibition space is the replica of the grave. The orientation of the burial chamber reconstructed in the burial mound agrees with the original findings. The burial chamber is viewed from the west, i.e. from the side of the grave that was already excavated when it was found. The profile known from the excavation report is reproduced under the burial chamber. The dead is represented in the burial chamber by a clad plaster figure, the replicas of the torc, who wears gold arm rings and finger rings. To the left of her head is a replica of the bar link chain, the amber necklace and the box, and to the right is the replica of the mirror. The representation of the burial situation in the burial chamber does not match the findings in every detail, in order to give the viewer an optimal view of the finds. One of these details is that only the deceased and some of the finds are lying on a mat, whereas the finds of fibrous tissue on one of the bronze bowls indicate that the entire floor of the chamber was covered with a reed or bast mat. Likewise, the representation of the drinking utensils on a table together with a gold-plated bronze jug is not without controversy. Remnants of wood that had been preserved under the bronze jug point to the wooden floor as the origin. In addition, a piece of wood was also found under the small bronze bowl, which is probably a remnant of the plank floor. Fibrous fabric of the floor covering and the remains of a linen fabric adhered between this wood residue and the shell.

literature

- Peter Buwen: The grave of the Celtic princess in Reinheim. (= Saarpfalz. Sheets for history and folklore. Special issue 2003), Saarpfalz-Kreis, 2003, ISSN 0930-1011 .

- Rudolf Echt : The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999.

- Alfred Haffner: Who was the lady from Reinheim. In: European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim. 2500 years of history (= Dossiers d'Archéologie. Special issue No. 24). ÉDITIONS FATON, 2013, ISSN 1141-7137 , pp. 20–33.

- Josef Keller: The princely grave of Reinheim (St. Ingbert district, Saarland). Preliminary report. In: Germania . Gazette of the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute, Issue 33, No. 1/2, 1955, ISSN 0016-8874 , ( digitized version )

- Josef Keller: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds. Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965.

- Walter Reinhard: The Celtic princess of Reinheim. Foundation European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, Saarpfalz-Kreis, 2004, ISBN 978-3-9807983-3-4 .

- Walter Reinhard: The princely seat of Reinheim. In: European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim. 2500 years of history (= Dossiers d'Archéologie. Special issue No. 24). ÉDITIONS FATON, 2013, ISSN 1141-7137 , pp. 8-15.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Josef Keller: The princely grave of Reinheim (St. Ingbert district, Saarland). Preliminary report. In: Germania . Gazette of the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute, Edition 33, No. 1/2, 1955, ISSN 0016-8874 , pp. 33–42, here p. 33 ff. ( Digitized version )

- ^ Josef Keller: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds. Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, page 11, note 27.

- ↑ Walter Reinhard: Owner of the Roman villa a legal successor to the princess? . In: Celts, Romans and Germanic tribes in Bliesgau (= preservation of monuments in Saarland. Volume 3). Foundation European Cultural Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, Gersheim 2010, ISBN 978-3-9811591-2-7 , p. 215.

- ^ Josef Keller: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds. Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz on commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, pp. 11-13.

- ^ Josef Keller: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds. Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz on commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, pp. 11-14.

- ^ Josef Keller: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds. Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, p. 17.

- ^ Walter Reinhard: The grave of the Celtic princess In: The Celts in Saarland (= preservation of monuments in Saarland . Volume 8). Ministry of Education and Culture - Landesdenkmalamt, 2017, ISBN 978-3-927856-21-9 , p. 302.

- ^ A b Rudolf Echt: Fund criticism In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 21–33.

- ^ A b Walter Reinhard: The early Celtic princess of Reinheim . In: Celts, Romans and Germanic tribes in Bliesgau (= preservation of monuments in Saarland. Volume 3). Foundation European Cultural Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, Gersheim 2010, ISBN 978-3-9811591-2-7 , p. 183.

- ^ Rudolf Echt: Reinheim, Tummulus C: le tertre oublié de la nécropole du Katzenbuckel. In: F. Boura (Ed.), J. Metzler (Ed.), A, Miron (Ed.): Actes du XIe Colloque de l'Association Française pour l'Etude des Ages du Fer en France non Méditerranéenne. (= Archaeologia Mosellana 2 ), 1993, ISBN 3-927856-02-9 , pp. 317-330.

- ↑ Josef Keller: The main profile . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, pp. 20–30.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: Fund criticism In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, p. 31.

- ↑ a b c Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 35–131.

- ↑ a b Josef Keller: Discovery and excavation of the graves on the Katzenbuckel . Grave A (tomb of the princess) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, p. 19.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: The dead ritual as an expression of role and rank. The dowry for the dead In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 153–160.

- ↑ a b Josef Keller: Description of the grave goods. Grave of the princess (grave A) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz on commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, pp. 31–77.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, p. 35.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, p. 39.

- ^ Josef Keller: The Prince's Grave of Reinheim (St. Ingbert District, Saarland). Preliminary report. In: Germania . Bulletin of the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute, Edition 33, No. 1/2, 1955, ISSN 0016-8874 , pp. 33–42, plate 8. ( digitized version )

- ↑ Josef Keller: Description of the grave goods. Grave of the princess (grave A) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, plate 16.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, p. 72.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, p. 84.

- ^ Josef Keller: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds. Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, plate 29.

- ↑ Josef Keller: Discovery and excavation of the graves on the Katzenbuckel. Grave A (tomb of the princess) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publisher of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, p. 17, note 33.

- ↑ Josef Keller: Description of the grave goods. Grave of the princess (grave A) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, p. 52, no. 66.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 96-103.

- ↑ Josef Keller: Description of the grave goods. Grave of the princess (grave A) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, p. 44, no. 25.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, p. 82.

- ^ A b Walter Reinhard: The early Celtic princess of Reinheim . In: Celts, Romans and Germanic tribes in Bliesgau (= preservation of monuments in Saarland. Volume 3). Foundation European Cultural Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, Gersheim 2010, ISBN 978-3-9811591-2-7 , p. 190, illustration 180 and p. 191.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 128-131.

- ↑ Josef Keller: Description of the grave goods. Grave of the princess (grave A) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, page 18.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, p. 196 f.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Echt: The dead custom. Wine and donation bowls. In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 163–200.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 123–126.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, p. 83.

- ↑ Josef Keller: Description of the grave goods. Grave of the princess (grave A) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, p. 69, no. 198.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: On the cultural-historical position of the finds (with additions and corrections to Keller's find catalog) In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 104-106 and illustration on p. 107.

- ↑ a b Josef Keller: Discovery and excavation of the graves on the Katzenbuckel. Grave A (tomb of the princess) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, p. 22.

- ^ A b Rudolf Echt: Fund criticism In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 21–33.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: Reinheim in the prehistoric and early historical literature In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 13-19.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: The princely graves of the early La Tène culture: Chronology, chorology In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 257–283.

- ^ Alfred Haffner: Who was the lady from Reinheim? In: European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim. 2500 years of history. (= Dossiers d'Archéologie. Special issue No. 24). ÉDITIONS FATON, 2013, ISSN 1141-7137 , p. 22.

- ^ Nicole Nicklisch, Barbara Bramanti, Kurt Werner Alt: On the anthropology of the early La Tène skeleton finds from Hill 1 and Hill 3 of Reinheim "Horres" . In: Walter Reinhard: Celts, Romans and Teutons in Bliesgau , Preservation of Monuments in Saarland 3, Foundation European Cultural Park Bliesbrück-Reinheim, 1st edition 2010, ISBN 978-3981159127 . Pp. 231-243.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: The dead ritual as an expression of role and rank. The grave custom In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 134–143.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: The dead ritual as an expression of role and rank: Die Bestattungssitte In: Das Fürstinnengrab von Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 144–150.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: The dead ritual as an expression of role and rank. The dowry for the dead In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Alfred Haffner: Who was the lady from Reinheim. In: European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim. 2500 years of history (= Dossiers d'Archéologie. Special issue No. 24). ÉDITIONS FATON, 2013, ISSN 1141-7137 , p. 33.

- ^ Athenaios Deipnosophistai, 3, 36 . In: Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists. with an English Translation by Charles Burton Gulick. Cambridge Harvard University Press, William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1927.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: The dead ritual as an expression of role and rank. The dowry for the dead In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 163–200.

- ^ Alfred Haffner: Who was the lady from Reinheim. In: European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim. 2500 years of history (= Dossiers d'Archéologie. Special issue No. 24). ÉDITIONS FATON, 2013, ISSN 1141-7137 , pp. 20–33.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: The dead ritual as an expression of role and rank. The dowry for the dead In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 200–214.

- ↑ Walter Reinhard: Other Celtic princely graves in the princess' necropolis? . In: Celts, Romans and Germanic tribes in Bliesgau (= preservation of monuments in Saarland. Volume 3). Bliesbruck-Reinheim European Cultural Park Foundation, Gersheim 2010, ISBN 978-3-9811591-2-7 , pp. 201–202.

- ↑ Rudolf Echt: The dead ritual as an expression of role and rank. Conclusions In: The princess grave of Reinheim. Studies on the cultural history of the early La Tène period. (= BLESA Volume 2). Publication of the European Culture Park Bliesbruck-Reinheim, 1999, pp. 214–222.

- ↑ Peter Buwen: The grave and the grave goods. In: The grave of the Celtic princess in Reinheim. (= Saarpfalz. Sheets for history and folklore. Special 2003), Saarpfalz-Kreis , 2003, ISSN 0930-1011 , pp. 14-19.

- ↑ Josef Keller: Description of the grave goods. Grave of the princess (grave A) . In: The Celtic princess grave of Reinheim I. Excavation report and catalog of the finds . Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz in commission from Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Mainz, 1965, p. 70, no. 200 and p. 71, no. 205.

Coordinates: 49 ° 8 ′ 1.8 ″ N , 7 ° 10 ′ 51 ″ E