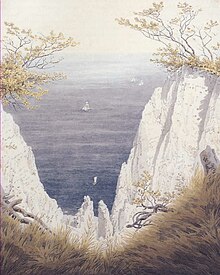

Chalk cliffs on Rügen

|

| Chalk cliffs on Rügen |

|---|

| Caspar David Friedrich , 1818 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 90.5 × 71 cm |

| Art Museum Winterthur - Reinhart am Stadtgarten |

Chalk Cliffs on Rügen is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich from 1818 . The painting in oil on canvas in the format 90.5 × 71 cm is a major work of German Romanticism ; it is in the Kunst Museum Winterthur - Reinhart am Stadtgarten in Winterthur .

Image description

The painting shows a cliff by the sea with bizarre, bright white rocks. Two beeches touch each other at the upper edge of the picture, on the right a tree dominating the picture stands opposite a small tree that is only barely held by the roots. There are three people on the narrow grassy foreground; it appears to be a tour company. A woman with a red dress and her hair set high is sitting in the grass. She holds on to a withered branch with her left hand and points with her right hand at a flower and at the same time in the direction of the cliffs. In the center of the foreground a man crawls anxiously on the ground, peeks cautiously over the edge and tries to hold his hands in the grass. He has blond hair and a blue frock coat, top hat and walking stick have been discarded. On the right a man stands bravely on some thin branches above the depths, leaning his back against a tree stump. He has his arms crossed over his chest and is wearing a green-gray frock coat and hat. He looks out to sea. The few waves in the calm sea reflect the midday sun. Two white sailing boats are on their way. The colors give the picture a cheerful character.

Structure and aesthetics

Friedrich gives up spatial continuity here more than in other of his compositions. It offers the viewer a space or surface construction that is unique in its radicalism. Dispensing with the depth axis, three spatial zones are arranged parallel to the image, separated from one another in terms of color and motif. The front room zone opens up in the picture surface as a kind of window onto the sea, framed very traditionally by rocks and trees, through which the three people perceive the “outside world”. After that, the area of the rugged, ghostly white rocks forms the greatest possible contrast to the seemingly endless sea. The two ships are located at some distance from each other, as if on an immaterial sheet, and yet are of the same size. This is how the vertical tension between near and far is mediated. The effect of a dangerous abyss is created by the narrow grass bank, the incision in the cliffs and the blue-green sea rising like a wall behind it, which only fades into pink-blue just below the branches of the trees. The line of the vertical golden section on the left runs through the deepest notch in the chalk cliff and has a harmonious effect on the picture, allowing the eye to relax. Depending on the intention, the central shape of the picture is viewed as a heart shape or as a full rock funnel. If you turn the picture upside down, the negative shape of the funnel changes into the positive shape of a bizarre mountain peak. The rocks with no life whatsoever contrast with the accuracy with which the figures and vegetation are depicted in the foreground. The colored triad green-white-blue is enhanced by the red dress of the woman. For Friedrich's mood in painting, this picture is an unusually festive one. It can hardly be explained whether the fascination of the representation arises from its formal boldness or the contrasting colors.

The landscape

The landscape of the painting can certainly be located on the island of Rügen on the chalk cliffs of the Kleine Stubbenkammer , south of the Victoriaus view, if Friedrich also composed his cliffs from sketches of various rocks. The right rock face comes from the Great Stump Chamber. In several travel guides and in some Rügen literature, the Wissower clinics are incorrectly given as motivic inspiration. These did not yet exist at the time the painting was created, but were created later due to erosion. In the picture, the rocks are more rugged and steeper than those carved by wind and weather in nature. The actual position of the painter could be determined by a steel engraving by Johann Friedrich Rosmaessler from 1835.

Image interpretation

Access to the interpretation of the image is gained through the identification of the image personnel. Since there is no tradition on this and the biographical context does not allow any conclusive answers, the picture narratives result from the interpretation patterns typical of the painter's work. The sense of image is read under religious, political, philosophical, psychopathographic as well as form and color symbolic aspects. Because the painting was created after Friedrich's honeymoon trip with his wife Caroline in the summer of 1818, which also took the couple to the island of Rügen, the interpretation as a “wedding picture” is apparently plausible and popular.

Virtues

For a religiously determined meaning in an allegory , Helmut Börsch-Supan assigned the Christian cardinal virtues to the people and colors of the picture . The woman with her red dress stands for love, the man crawling on the ground in his blue skirt for faith and the man in green-gray clothes leaning against a tree stump for hope. The lean figure crawling on the floor can be identified as Friedrich by the round skull and blond hair, the woman as his wife Caroline and the second husband Friedrich's brother Christian. The hat lying on the ground is interpreted as a sign of humility. With the virtues of faith, love and hope, a Protestant tradition in art is addressed that corresponds to Friedrich's theological understanding.

View of nature

Werner Hofmann recognizes three different ways of dealing with nature in the painting. This is the point of the picture construction. The woman points into the abyss, the man examines blades of grass and the other man looks out to sea. Here, the theming of proximity and distance is linked to human expectations.

Wedding picture

Jens Christian Jensen introduced the thesis of the wedding picture in interpretation and thus achieved a broad consensus among art historians (including Wieland Schmied , Werner Busch ). The scene depicted is an allegory of Friedrich's love for his wife thanks to the heart-shaped frame of trees and grass stage and the festive sound of the whole. The painting belongs to the tradition of romantic friendship pictures, such as Philipp Otto Runge's triple portrait from 1805, in which the painter depicts himself with his wife and brother. While Runge's assignment of the people is clear, the third person on the chalk cliffs brings with them a differently resolved interpretation problem. Jensen sees the man leaning against the tree painted as Friedrich in his younger years. The one crawling on the ground represents a person who somehow mediates between the two married couples. Since the person constellation does not provide a picture of a couple on their honeymoon, the painter's attitude towards marriage is seen as difficult. Obviously it is about complicated relationship problems. Friedrich would become aware of the differences between himself and Caroline.

"[...] when I tell her about the trip from Greifswald to Rügen, then she probably shudders, hides a little under my coat and then speaks softly and fearfully: Wherever you go, I'll go with you, and when you go to that Sink into the lake, I sink with you. "

Double portrait

Because the second male person in the picture can hardly be assigned to a coherent sense of the picture, one recognizes a double self-portrait of the artist in a further interpretation variant in the two male figures. This thesis is derived from the comprehensible double viewing experience, down into the gorge and onto the sea, divided between the two men. A psychoanalytic level of interpretation describes the double self-image as an expression of a division of the man into a loving-affectionate and an independent, freedom-loving personality; influenced by traumatization and loss of objects in childhood. The look into the abyss could be a look into the time of painful events and justify the self-created doppelganger. So the painting would be an inner portrait of the artist of himself, a hardly masked form of self-analysis. Double portraits that show the painter in his split personality have existed since the Renaissance. An example of this are the Two Laughing Men by Hans von Aachen from around 1574 .

Demagogue symbol

The political interpretation sees the man leaning against the tree stump as a " demagogue " due to his forbidden commitment to confess with Barrett . In the eyes of the “demagogues”, the cylinder as headgear characterized the man who crawled on the floor in his fear and looked a little ridiculous as a “ Philistine ”. The painter is assumed to have a caricaturing intention. Peter Märker sees a similar constellation in a drawing that Wilhelm Hauff made in 1822 as a fraternity member in Tübingen . The informer among the fraternity members wearing berets wears a large top hat. During the time of the demagogue persecution, Friedrich took the old German costume into the picture for political reasons. Here, too, the double vision is sought. The distant view stands for hope for the future, the in-depth view for fear in the present. What speaks against this theory is that Friedrich uses a cylinder lying on the ground in other pictorial contexts, for example in the painting Mountain Landscape with Rainbow from 1810 and in the drawing Wanderer at the milestone from 1802.

Early Ruegen tourism

The motif of an excursion company at the stump chamber can be seen as a zeitgeist. The chalk cliffs had long been developed by early Ruegen tourism around 1820. The Nordic-Ossian poetry by Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten , some travel guides, geological treatises and Friedrich's Rügen drawings from around 1800 quickly made the Baltic island popular. The sublime feeling of looking into the distance from the chalk cliffs and the shuddering at the sight into the depths, i.e. Friedrich's double look, had become the topos of even clarified considerations of the coastal landscape. This experience was also described by the geographer Johann Jacob Grümbke in 1805 .

"On this top [of the Königstuhl] one feels for a first moment seized by a mute dismay, a certain fear constricts the chest, and the gaze, unable to grasp the whole, wanders unsteadily around the expanded field of vision, soon from the Drawn to the prospect of the great gorge and the small lumber room, now dipping fearfully down to the depths of the beach, now flying over the infinite semicircle of the blue sea, and peering in vain at a twilight coast of the opposite Sweden, he finally discovers Arkona on his left, which is in front of this size humbly humiliated. "

Anecdotal

In August 1815, Friedrich emigrated to Rügen with his friend, the Saxon mint official Friedrich Gotthelf Kummer. While climbing the chalk cliffs, Kummer found himself in a situation that made it impossible to move forwards or backwards without running the risk of falling into the depths. Friedrich had to get help to get Kummer out of the predicament. As in the painting, the painter actually crawled anxiously towards the abyss to communicate with his friend.

"At this terrible moment I called F. to the sidelines and gave him several assignments to my family, which I considered to be their farewell."

This event is used in some interpretations as a memory processed in the picture.

Sketches and studies

The rock formation shown in the picture is based on the drawings of a double sheet, dated August 11, 1815, from the still preserved Oslo sketchbook. Both drawings are described with the title Small Stubbenkammer on Rügen . The sketches were made during the painter's trip to the island of Rügen in the summer of 1815 together with the Dresden mint official Friedrich Gotthelf Kummer. The aft sailing ship is studies of sailing ships from 6/7. Taken from August 1818, belonging to the Oslo sketchbook of 1818. This drawing was made during Friedrich's honeymoon in 1818 on the island of Rügen.

The opposite image

Also with the title Chalk Cliffs on Rügen there is a watercolor by Friedrich's hand that was created after 1825, which can be read as a counter-image or a gloomy epilogue. The picture shows the same sea view with notable changes. The people are missing in the landscape, the framing trees are stunted, the rock pushes further into the field of vision, but appears bleak, gray and with a reduced shape, the heart shape is no longer closed at the top - the heart has broken apart. The interpretation of the wedding picture thesis assigns the watercolor to a painter who aged prematurely, lonely and tormented by jealousy. Werner Hofmann even sees this disturbance in Friedrich's private fate as part of the psychography of the epoch, and finds parallels in Friedrich Hölderlin's Hyperion and Franz Schubert's Winterreise .

Provenance

The painting, dated 1818, appeared under lot number 58: Chalk cliffs on Rügen, 3 person staffage in the auction catalog of October 7, 1903 (catalog no. 1350) of the Berlin Rudolph Lepke's Kunst-Auctions-Haus . The picture was offered in the catalog as a work by Carl Blechen , who had also painted the landscape near Stubbenkammer. After that, the work was in the collection of the Jewish collector Julius Freund . It was not until 1920 that the art historian Kurt Karl Eberlein and Freund's art advisor, the curator of the Berlin National Gallery Guido Joseph Kern (1878–1953), attributed the work to Caspar David Friedrich. In 1930, during the Great Depression , Freund sold the chalk cliffs to the Swiss art collector Oskar Reinhart for 50,000 Reichsmarks through Fritz Nathan ; with a large part of his collection, the painting was later transferred to the Oskar Reinhart Foundation in Winterthur.

Classification in the complete work

The painting is unique in Friedrich's work in its bright, colorful solemnity, but also in its radical spatial or surface construction. The Rügen theme is more or less represented in all of the painter's creative periods, but it has reached a climax with the chalk cliffs . In the series of images shaped by women, the painting is given an exceptional place. Compared to motifs in the gazebo , the woman in front of the setting sun , the woman at the window or the garden terrace , the woman in the red dress seems to have been freed from the usual static and lack of relationships. With the man leaning on a tree stump, a type of figure is represented here that can be found around 1818 in the paintings Gazebo , The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog , On the Sailor and Two Men Contemplating the Moon .

Effects in art

In its unusual composition, the painting has not inspired any comparable works. However, with the Rügen theme and the chalk cliff motif, Friedrich left recognizable traces in his generation of artists and subsequent generations of artists. He made the Baltic island popular as an artist motif. This is shown by works by Karl Friedrich Schinkel , Carl Blechen , Carl Robert Kummer and Johann Friedrich Boeck.

reception

In the still relatively short history of reception of the chalk cliffs , a barely manageable amount of text interpretations was presented, which illuminate all conceivable levels of interpretation. The picture is the most frequently used motif on covers of literature on Caspar David Friedrich and is effectively used for tourist advertising for the island of Rügen and the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania . In 1939 the painting appeared in the French magazine Minotaure as an example of angoisse romantique (romantic fear of the heart).

Experience in nature

The landscape of Friedrich's picture today belongs to the Jasmund National Park . The view from the rocks to the sea is impressive to experience at the Königsstuhl, the most famous chalk cliff ledge. In the Königsstuhl National Park Center , you can find out more about the landscape of the painter's motif and the changes to the chalk cliffs over the past 200 years.

literature

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné)

- Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Publishing house CH Beck, Munich 2003.

- Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006.

- Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011.

- Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions . Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974.

- Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 .

- Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999.

- Barbara John: Caspar David Friedrich - Chalk cliffs on Rügen , Seemann Henschel, Leipzig 2005.

- Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 124.

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

- Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich on Rügen . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1998, ISBN 90-5705-060-9 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 124

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 127

- ^ Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 110

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work. DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 177

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich on Rügen. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1998, p. 84

- ↑ Radu Bogdan: Metaphysics and Reality in Caspar David Friedrich's painting “Chalk Cliffs on Rügen” . (1818). In: Hannelore Gärtner (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich, life, work, discussion . Berlin 1977, p. 179

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich on Rügen . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1998, p. 87

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 127

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work. DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 177

- ^ Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 102

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 2008, p. 118

- ↑ Caspar David Friedrich: Letter from Caspar David Friedrich from Dresden to his brother Heinrich from March 26, 1818 . In: Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in Letters and Confessions, Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 35

- ^ Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 99

- ^ Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 112

- ^ Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 103

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 125

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), pp. 208, 120 f.

- ^ Werner Busch: Caspar David Friedrich. Aesthetics and Religion . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 113

- ^ Johann Jacob Grümbke: Forays through the Rügenland . Leipzig 1988, p. 101

- ^ Friedrich Gotthelf Kummer's diary notes . Quoted in Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich on Rügen. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1998, p. 85

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 682 f.

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich on Rügen. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1998, p. 82

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 748

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 772

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 127

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work. DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 181

- ^ Papers on the event of the same name at the Oskar Reinhart Museum in Winterthur on August 28, 2014 , Stäpfli Verlag AG, Bern (2015), p. 56/57

- ^ Papers on the event of the same name at the Oskar Reinhart Museum in Winterthur on August 28, 2014 , Stäpfli Verlag AG, Bern (2015), p. 56/57

- ↑ Götz Adriani (ed.): The art of acting. Masterpieces from the 14th to the 20th centuries by Fritz and Peter Nathan. Hatje Cantz Verlag 2005, page 49

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich on Rügen. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1998, p. 85