Teal

| Teal | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Teal ♂ ( Anas crecca ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Anas crecca | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The teal ( Anas crecca ) is a bird art from the family of the ducks and belongs to the genus of authentics swimming ducks ( Anas ). Teals are among the most numerous and widespread species of duck in the northern hemisphere. They are gregarious ducks that can easily be recognized by their small build: at 35 to 36 cm in length, it is the smallest species of duck in Europe and North America. It is hardly longer than a city pigeon . In Central Europe it is a widespread and regionally frequent breeding bird, which in some areas is even an annual bird. In the winter months it is a frequent migrant and guest bird.

The North American teal is viewed by some authors as an independent species and is thus described as Anas carolinensis . However, it differs only slightly from the teal and is generally considered to be one of its subspecies , Anas crecca carolinensis .

features

Adult teal appearance

Teals weigh between 250 and 400 g, with the males being slightly heavier than the females.

As is usual with many ducks, the teal also shows a pronounced sexual dimorphism. The drake has a bright maroon head. On both sides of the eye there is a broad, shiny green and curved stripe. This extends to the neck and is framed by a creamy white border. This yellow-white contour line is missing in the North American teal. The beak sides are orange to greenish in color in both sexes.

In contrast to the similarly small teal duck ( Anas querquedula ), the breast is brightly colored in both sexes. The male's front breast is yellowish with dark brown mottling. It is sharply set off from the chestnut front neck. A buttery yellow triangle shines on both sides of the black feathered rear of the drake. The conspicuous yellow spots are an important species recognition feature in field observation. The light gray color on the back is interrupted by a white longitudinal band. A black longitudinal band runs parallel to it. The sides of the body are finely striped gray and white. In both sexes the wing mirror is colored bright green and has a broad white border in front. In the simple dress that the drake wears after moulting , it resembles the female. The change from the splendid to the plain dress is between June and August for the males. Between September and November they switch back to their splendid dress.

In contrast to the male, the females wear an inconspicuous brownish plumage all year round, an external differentiation of the subspecies is considered almost impossible in female birds. In the females, the back and shoulder area are almost brown-black, while the flanks are gray-brown. The plumage on the upper side of the body is roughly patterned like scales. On the head, a light vertical stripe runs over the eye and a dark, clearly separated longitudinal stripe through the eye. The cheeks are light and the throat is whitish to yellow-brown. In the resting plumage the plumage of the female has a larger proportion of gray. The youth dress corresponds to the rest dress of the female adult birds. In swimming female teals, the green wing mirror is usually visible at the back of the body. This can be used as a distinguishing feature to the similarly colored tartan females.

The mating call of the drake is a bright "krrik" or "krílük" which is much more common to hear as the "fibíb" of the Stock drake . The calls of the female are clearly brighter and more nasal than those of the mallard.

On the water she usually swims with her head pulled in and thus appears slightly squat. It is typical for this species that it flies up almost vertically from the water. Outside the breeding season, it is social and often forms separate groups.

Appearance of the downy chicks and fledglings

The downy chicks have a brown headstock. The back of the neck, the back and the sides of the body are also brown. Yellow areas of color can be found on the wings, on the back and on the fuselage. The underside of the body is creamy white. The chest, throat and chin are pale yellow. The sides of the head are a pale brown that is even lighter above the eye. Two narrow, parallel lines of color run across the halves of the face. These lines of color are somewhat variable in shape. In some downy chicks they converge behind the eye and occasionally they are slightly curved at the end.

Newly hatched downy chicks have a black and gray upper bill with a brown nail. The lower bill is flesh or cream colored. The legs, feet and webbed feet are blackish-gray, with the sides of the legs slightly lightened. In the growing teal, the upper bill increasingly changes color to a light blue-gray. The legs and feet fade to a bluish or olive gray.

Subspecies and occurrences

There are three subspecies of the teal:

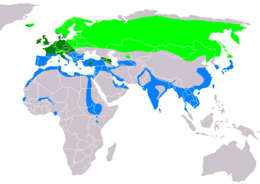

- The Eurasian subspecies Anas crecca crecca occurs in northern Europe and Asia . Its distribution area thus covers the entire northern and central part of the Palearctic and thus extends from Iceland to the Siberian Pacific coast. The distribution area extends south to the Alps and the Caucasus . The wintering area of the European-West Asian population extends from central and western Europe to Africa , the eastern populations winter in India and Southeast Asia.

- The slightly heavier subspecies Anas crecca nimia occurs in summer in Northwest America and the Aleutian Islands . In winter she moves to the south of North America.

- The North American teal ( Anas crecca carolinensis ) occurs in summer in Canada and the Prairie Pothole region of the United States and breeds there high in the north. In winter they migrate to the southern regions of the United States and Mexico .

The teal is predominantly a migratory bird, but it is also a partial migrant in some areas of its range. The main wintering areas can be found in the south and west of Europe, on the coastal areas of Denmark and Central Europe, in the Alpine foothills, in south-east Europe as well as in the Black Sea and Caspian regions and the Middle East. Individual teals up to larger groups of teals migrate to areas south of the Sahara on their winter migration. For example, wintering birds can be found in Senegal and the Chad Basin. Withdrawal to the wintering areas can begin as early as July, and in Europe it peaks in October and November.

The moulting migration, on the other hand, is only poorly developed in Western and Central Europe. A smaller number of moulting quarters can be found in Denmark, the Netherlands and Bavaria, for example.

habitat

Most of the world's teal populations live in the boreal coniferous forest zones and in the strauchtundren .

For breeding , the teal is dependent on shallow, nutrient-rich small bodies of water in moors and on the tundra . She prefers those waters that have well-developed riparian vegetation. Heathland and moor lakes that are completely enclosed by the forest are also used. However, it also breeds in the floodplains of river valleys, on islands in larger pond areas and on the archipelago islands on the Swedish and Finnish Baltic coasts.

On the train she prefers to rest in freshwater mud flats, where she combs the silt churned up by the tide for small annelid worms ( little bristles ). It can often be observed in clearing ponds, on the seashore in lagoons and in the Wadden Sea.

nutrition

Similar to the mallard, it is not very particular about its food. It uses the food supply in the silt and bank zone. Depending on the food available, the vegetable or animal components can dominate your diet. In late summer, at least in Central Europe, you can even see them looking for grain in harvested stubble fields.

When foraging for food, the little duck depends on water that is no more than 20 cm deep. With their short necks, they cannot be successfully found in deeper waters. In winter quarters, it often rests during the day and only looks for food at night. Foraging at sea depends on the tide.

Reproduction

As with all members of the genus of the actual swimming duck, the pairs of the teal can be found together until late winter, the drake lets his "krrik" be heard even when it is already firmly mated. The focus of courtship begins when the teals have returned to the breeding grounds. The courtship includes pursuit flights with which the territories are demarcated from other breeding pairs.

Teals make their nests well hidden in the bank vegetation along the water. Occasionally, nests can be found that are built some distance from the water. From the end of April, the female lays around eight to twelve eggs, which are creamy white to greenish in color. With the beginning of the laying season, teals begin to lead a very inconspicuous life. During this time they prefer to stay in the dense bank vegetation.

The nest consists of a hollow, which is mainly lined with grass and dunes. It is usually found hidden under a tuft of grass or a bush. The nest is built by the female alone. The nesting material is collected from the nest while sitting. In the southern areas of distribution, eggs are laid between the end of March and the beginning of April. In their northern distribution areas, the egg-laying does not begin until mid-May. Only one clutch is raised per year. A clutch usually consists of eight to eleven eggs. They are white in color with a yellowish tinge.

The eggs are only incubated by the female. It begins with the hatching business after the last egg of the clutch has been laid. Towards the end of the breeding season, which lasts around 21 to 23 days, the drakes leave the duck to moult. It takes only 53 days from the eggs to fledglings. The female is solely responsible for rearing. She prefers to stay with the chicks in the dense bank vegetation. Only when the young birds have fledged from about their 44th day of life does the female go to the open water with them. On average, four to five young per brood grow up.

Duration

The total European population is estimated at around 900,000 to 1.2 million breeding pairs for the year 2000. About two thirds of them live in the European part of Russia and about 230,000 to 380,000 breeding pairs in Fennoscandinavia . In Central Europe, the population is estimated at 7,600 to 11,000 breeding pairs. In Germany between 3,700 and 5,800 breeding pairs and in Austria between 70 and 120 breeding pairs (census 1995–1999 or 1998 and 2002). The species is largely absent in Switzerland, where only between one and three breeding pairs breed. In the Red List of Germany's breeding birds from 2015, the species is listed in Category 3 as endangered.

Presumably, the breeding bird population in Central Europe used to be larger than it is today, but the population development for this species over longer periods of time has not been documented. The decline in populations is mainly concluded indirectly from the loss of habitat and the impairment of suitable breeding waters through hunting and intensified agriculture, among other things. Since the species only searches for food in shallow water areas, the impairment caused by ingestion by lead shot is particularly great. The species is also prone to botulism . In particular, the destruction ( potting and cultivation ) of the moors is likely to have had a negative impact on the population. Where the rewetting of moors was carried out in nature reserves , a considerable increase in the breeding population and re-colonization was achieved regionally. In Eastern Europe, where there was relatively little damage to the habitat, the teal population is stable to rapidly increasing. A research team that, on behalf of the British environmental authority and the RSPB, investigated the future development of the distribution of birds on the basis of climate models, however, assumes that the teal will disappear over a wide area in Western and Central Europe by the end of the 21st century becomes. According to this forecast, the distribution area will decrease significantly and shift to the north. According to these models, only the region of the Alps and the coastal regions of Belgium, Holland and Germany remain as central European distribution centers.

The numerous teals resting on the train in Central Europe have to suffer from the destruction of the freshwater mudflats, as they are less able to build up fat reserves in less productive shallow waters.

breed

Teals have long been kept as ornamental poultry. In Europe this is primarily the native subspecies Anas crecca crecca . The keeping of the other subspecies is considered to be problematic, as the subspecies can be mixed up in captive refugees.

literature

- Hans-Günther Bauer, Einhard Bezzel , Wolfgang Fiedler (eds.): The compendium of birds in Central Europe: Everything about biology, endangerment and protection. Volume 1: Nonpasseriformes - non-sparrow birds. Aula-Verlag Wiebelsheim, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89104-647-2 .

- Tom Bartlett: Ducks and geese. Crowood, Marlborough 1986-2002, ISBN 1-85223-650-7 .

- John Gooders, Trevor Boyer: Ducks of Britain and the Northern Hemisphere. Dragon's World, Surrey 1986, ISBN 1-85028-022-3 .

- Hartmut Kolbe: The world's ducks. Ulmer, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8001-7442-1 .

- Erich Rutschke: Europe's wild ducks - biology, ecology, behavior. Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden 1988, ISBN 3-89104-449-6 .

Web links

- Anas crecca in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 30 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings for Anas crecca in the Internet Bird Collection

- J. Blasco-Zumeta, G.-M. Heinze: Teal. ( Memento from December 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 3.4 MB; eng.)

- Teal feathers

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christopher S. Smith: Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventure Press, Belgrade (Montana) 2000, ISBN 1-885106-20-3 , p. 66.

- ↑ E. Rutschke: The wild ducks of Europe - biology, ecology, behavior. 1988, p. 191.

- ↑ HG Bauer et al.: The compendium of birds of Central Europe. Volume 1, 2005, p. 92.

- ↑ Collin Harrison, Peter Castell: Field Guide Bird Nests, Eggs and Nestlings. revised edition. HarperCollins Publisher, 2002, ISBN 0-00-713039-2 , p. 73.

- ↑ Christopher S. Smith: Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventure Press, Belgrade (Montana) 2000, ISBN 1-885106-20-3 , p. 66.

- ↑ a b c d e f H. G. Bauer among others: The compendium of birds of Central Europe. Volume 1, 2005, p. 91.

- ↑ E. Rutschke: The wild ducks of Europe - biology, ecology, behavior. 1988, p. 193.

- ↑ E. Rutschke: The wild ducks of Europe - biology, ecology, behavior. 1988, p. 193.

- ↑ Collin Harrison, Peter Castell: Field Guide Bird Nests, Eggs and Nestlings. revised edition. HarperCollins Publisher, 2002, ISBN 0-00-713039-2 , p. 72.

- ↑ Collin Harrison, Peter Castell: Field Guide Bird Nests, Eggs and Nestlings. revised edition. HarperCollins Publisher, 2002, ISBN 0-00-713039-2 , p. 72.

- ↑ J. Gooders, T. Boyer: Ducks of Britain and the Northern Hemisphere. 1986, p. 47.

- ↑ J. Gooders, T. Boyer: Ducks of Britain and the Northern Hemisphere. 1986, p. 47.

- ↑ Christoph Grüneberg, Hans-Günther Bauer, Heiko Haupt, Ommo Hüppop, Torsten Ryslavy, Peter Südbeck: Red List of Germany's Breeding Birds , 5 version . In: German Council for Bird Protection (Hrsg.): Reports on bird protection . tape 52 , November 30, 2015.

- ↑ HG Bauer et al.: The compendium of birds of Central Europe. Volume 1, 2005, p. 92.

- ^ Brian Huntley, Rhys E. Green, Yvonne C. Collingham, Stephen G. Willis: A Climatic Atlas of European Breeding Birds. Durham University, The RSPB and Lynx Editions, Barcelona 2007, ISBN 978-84-96553-14-9 , p. 78.