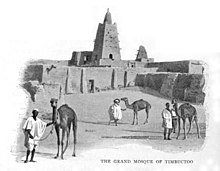

Timbuktu clay mosques

The clay mosques of Timbuktu are three mosques in the city of Timbuktu in Mali . It is believed that their origins go back to the 14th and 15th centuries. Since 1988, they include not only local cemeteries and mausoleums for World Heritage of UNESCO . Due to terrorist attacks, they have been on the Red List of World Heritage in Danger since 2012, after they were already registered from 1990 to 2005 .

history

After the turn of the first millennium of our era, Timbuktu developed into a flourishing trading post on the important caravan route from Egypt via Gao to the West African kingdom of Ghana, ruled by the Soninke . With the incursion of the Almoravids in the 11th century, Islamization began on Niger and Ghana fell.

The famous Arab geographer, Abū ʿUbaid al-Bakrī , described the conquest campaigns of the Almoravids and their extensive mosque construction in his work Kitāb al-masālik wa-'l-mamālik (= "Book of Ways and Kingdoms"). Two centuries later, the Mali empire of the Malinke became a regional hegemonic power. Their center was on the upper reaches of the Niger.

The Mali empire became famous not only through the records of the Muslim explorer Ibn Batuta . The pilgrimage of his fabulously rich ruler Mansa Musa , who initiated the economic boom and the associated cultural prosperity of the city for the 14th and 15th centuries, contributed to this. According to the local historical work from the 17th century, Tarikh el-Fettach , he is said to have endeavored to take descendants of the Prophet to Sudan in Mecca , whereupon four men of the Quraish tribe joined him. Intellectual elites founded university-like locations. Teaching took place in mosques. These were emblematic of the prosperity that took place, because they were part of the most magnificent clay architecture in Africa. Mansa Musa, it is believed, could have opened his gold box in the year of his return from Mecca to have the Djinger-ber Mosque (also Djingere-ber or Djingereber) and the Sankóre Mosque built.

Historical sources

Al-Bakrī and Ibn Batuta portray excerpts from the life of Mansa Musa and provide information about the aftermath of his rule, but remain silent on questions that affect the origin and history of the clay mosques.

Leo Africanus

The first description of the mosques in Timbuktu goes back to the Iberian Moors Leo Africanus, who converted to Christianity . In one of his standard works, Descrittione dell'Africa , it is stated in translation that

"... in the middle of the city is a mosque built with stones and lime mortar and built by an architect from Andalusia ..."

In 1600 his regional travelogue was translated into English, whereby Timbuktu increasingly penetrated the consciousness of Europe. The descriptions encouraged one to see Timbuktu in a mysterious, exotic light.

Tarikh as Sudan

The work of Abderrahmane Es Saâdi, the Tarikh as-Sudan , completed in Timbuktu in 1655 and written in Arabic, elaborates on the historical dimensions of the city's development:

“Later people started to settle in this place and the population grew according to the will of God .... Before that, the trading center was in Biru; one saw caravans from all countries gather there; and great scholars, pious people, rich people from every people and every country settled there ( Egypt , Audschila, Fessan , Ghadames , Dra , Tafilalet , Fez , Sus, Bitu ) .... At first the dwellings consisted of thorn hedges and from Thatched huts; then they were replaced by brick buildings. Eventually the city was surrounded by very low walls so that one could see from the outside what was going on. A large mosque (Djinger-ber) was built on it, which was sufficient for the needs, then the mosque of Sankóre. Anyone who stopped at the entrance to the city saw those who entered the great mosque: the city had so few walls and buildings at that time. ( Comments on the location of: Audschila (Udschila / Augila): oasis complex in Tripoli, today's Libya, Sus (kingdom in southwestern Morocco with the capital Taroudannt ). "

Es Saâdi adds at another point:

"He (Mansa Musa) seized this city and became the first ruler to subjugate it ... Kanka Musa, it is said, had the minaret of the Timbuktu mosque built ..."

In this respect, the completion of the work on the great mosque, Djinger-ber, is meant. Incidentally, as Heinrich Barth wrongly assumed, the work does not go back to the Maliki legal scholar Ahmad Bābā , although his works, which have been included in the collection of writings, have a lasting impact on Tarikh as-Sudan. Elsewhere it reports that the first prayer leaders of the great mosque were "blacks" during the rule of Mali and in some cases during the Tuareg era, and that Timbuktu was actually

"... been full of black students who diligently pursued science and virtue ..."

This statement was astonishing to the extent that when the two books were viewed together, Berbers and Arabs were mentioned as Timbuktu's scholars. The publicist Es Saâdi, himself a Berber by origin, noticed this on the occasion of his work as an imam of the Sankóre Mosque, which accompanied the business of government for the city administration, as it were by virtue of his office, because he did not have to rely on one of the many oral traditions, but was a personal source of testimony . The same chronicler writes about the Sidi Yahia mosque, which was built later:

“Mohammed Naddi had the well-known mosque built and appointed his companion and friend Sidi Jahja at Tadelsi as imam. Both friends died at the same time towards the end of the Tuareg rule ... They both buried next to each other in the same mosque. "

Tarikh el-Fettach

There is no evidence of the beginning of the Islamization of the city of Timbuktu. The Tarikh as-Sudan only states that Za-Kosoi, the 15th ruler of the Za dynasty founded by a Yemeni refugee, converted to Islam in 1009/10. The chronicle of Tarikh el-Fettach, which can be traced back to the authors Ibn al-Mochtar and Mahmud Kati, confirms this. It remains to be seen whether the dates are correct, because Africanists and epigraphers such as John Hunwick or Jean Sauvaget relocate the event to a much later period between 1078 and 1087. All information gathered in the two chronicles is based solely on oral tradition. Almost 50 years earlier, in any case, the Tarikh el-Fettach explains for Gao and thus even more for Timbuktu:

"In the year 961/2 the rulers of Goa were infidels."

Only the execution of Tarikh el-Fettach to the Sankóre Mosque is tangible:

“The mosque of Sankóre was built by a woman, a tall, pious and very wealthy lady, who was eager to do good works, as they say; but we do not know when this mosque was built. "

All that is known about this woman is her tribal membership to the Aghlāl. These days it is sometimes claimed that they can be traced back to the caliph Abū Bakr ; in fact, the Aghlāl rather go to the urberberischen tribe of Sanhaja ( lamtuna back) what einleuchtet when one considers that many members of this North African Berber people from the meaningless nascent trade center Walatas solved to get oriented to the south to Timbuktu. Members of the Sanhadscha Timbuktus (so-called Kunta ) claim for their part to be heirs of ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ . Mainly they placed the imams in the Sankóre mosque, this in a different practice to the Djinger-ber mosque, whose imams were recruited from Fulbe and Kābarīs in addition to Arabo-Berbers .

Mansa Musa is said to have sent a future imam from the Sankóre Mosque to Fez for training , which leads to the conclusion that the level of Islamic education in Niger was still very rudimentary.

Guesswork

Structural construction

When the three mosques were built cannot be reliably dated to this day. The archaeological research has this question also not yet been concluded. There are only temporal limitations, which in turn are based on the vague historical sources. What is certain, however, is that the mosques have been changed several times through renovations or new construction. Affected are the remaining Djinger-ber mosques , whose construction time is believed to have been around 1325/1327 (Mali subjugated Songhai for a short time and occupied Timbuktu in 1325 ), possibly dating back to the 13th century, the Sankóre , which was also at the time of the Mali Rulership is said to have been built, basically between 1325 and 1433, as well as the Sidi-Yahia , which is assigned to the year 1440. Three other mosques, approximately from that time, El-Hena , Kalidi and Algourdour-Djingareye , have been destroyed.

There is no knowledge of how the mosque was planned. The city chronicle Tarikh el-Fettach reports at best from a certain Qādī El-Aqib (legal scholar of Timbuktu) who is said to have received the order at the end of the 16th century to restore the mosques or, if not destroyed, to have them restored.

Librarianship

The mosques are said to have housed large libraries. Books originating from this are kept in the research facility IHERI-AB . The majority of around 100,000 preserved manuscripts date from the 13th to the 16th centuries, sometimes in the local languages of Songhai , Tamascheq and Bambara . The oldest datable document comes from the year 1204. Songhai King Mohommed Ture the Great in the 16th century is said to have sent valuable Koran editions to the Djinger-ber Mosque. Around 1900, larger parts of the Sankóre's holdings were lost when, in the face of the French occupation, Muslim scholars left the city and took the library contents with them. It is said several times that the mosque libraries should have held between 400,000 and 700,000 books. The Africa researcher John O. Hunwick, who had dealt with the question of the allocation of the existing manuscripts in the late 1960s, ultimately had to refrain from a reliable finding.

Common architectural features of the clay mosques

Classic construction type

The three mosques are built in the style of classic mosque architecture. There are prayer niches , main prayer halls with prayer room buildings , gallery-flanked courtyards and minarets . They also clearly show elements of the region, which in turn shape the northern Niger Inland Delta. The building material used was clay, which was specifically shaped. The mosques illustrate the special features of the architectural province of western and central Sudan . They shape an independent style region within which the concept of form and the expressed will to design can sometimes differ considerably from one another.

Courtyard mosque type

Dome mosques such as those found in the central Sudanese regions of Niger and Nigeria can hardly be found in Mali. Nor do double-tower or conical-roof mosques prevail, such as those found in the Volta-Niger region of the Ivory Coast and Ghana , or in the Oberniger region with Togo and Guinea . Timbuktu in the Middle Ages region is based on the early Islamic model of the court mosque. Court mosques can be found in the entire vertex of the Niger Arch (Niger knee) between Ségou and Gao , as well as the associated peripheral zones.

Medieval (Sahelian) peculiarities

The Djinger-ber Mosque and the Sankóre Mosque are characteristically built in the Sahelian style. The pillar walls are made of clay and there is a flat roof. The protruding “chimney bars” (in Songhai : toron ) that characterize the outer walls are characteristic. They form an external framework for renovation measures on the outer skin of the mosques. For better climbing ability, they often exist in duplicate. The wood comes from doum palms and acacia species . The Ethiopian palmyra palm is also used elsewhere in the Central Nigerian region . The toron beams are of no importance for the statics, but they are of high decorative value.

Both mosques are made of rectangular bricks made with wooden molds. Other attributes such as tubes and balls were made manually. The Sidi Yahia mosque only suggests the same architectural style in the core of the minaret after it was completely clad in the 20th century. Until its abolition were slaves used. Heavy rains , sandstorms and shifting dunes hit the buildings again and again. The historical source of Tedzkiret en Nisian testifies that the minaret of the Sankóre mosque collapsed in 1678. The minarets in these mosques are not free, but are enthroned on top of the buildings.

A special feature of the mosques is their architectural simplicity, which appears elongated, flat and connected to the earth. In the Niger knee and its neighboring regions up to the headwaters of the Volta , wall templates reinforced the walls of the facilities and structured the facades as pilaster strips or half / corner pillars. Although strut walls are rarely found today, they typically still pick up the sideshift in old mosques (clearly visible in the two historical photos above). The strong corner pillars served not only as architectural ornamentation, but primarily for stabilization. Otherwise, they contain neither rich decorations, tiles or ornate wood carvings, nor - apart from a chandelier in the Sidi Yahia Mosque - heavy hanging lamps enliven the interior of the mosque. The severity and unadornment are thus also reminiscent of the early Islamic court mosque. Diamond and incised patterns as well as hollowed ostrich eggs on the minaret tips characterize the simple local architectural style (partly on green glazed ceramic).

World Heritage Criteria

In December 1988, the World Heritage Committee in Paris found that certain parts of Timbuktu's old town were in special need of protection; this based on the following criteria:

- Criterion II: Timbuktu's holy places are living testimony to early African Islamization .

- Criterion IV: Timbuktu's mosques point in cultural and scientific terms to a golden age during the Songhai Empire .

- Criterion V: The architecture of the mosques, mostly preserved in the original to this day, is deeply rooted in the traditional construction method.

The world heritage protected mosques in detail

Djinger-ber Mosque (Friday Mosque)

Building history additions

The Djinger-ber Mosque is the from Granada originating, Andalusian architect Abu Eshaq Es-Saheli al-Touwaidjin attributed to the built the building in 1325 and is said to have for 40,000 with (h) qal. The construction was presumably initiated by Mansa Kankan Musa , the fabulously rich King of Mali , after he returned from Mecca from a pilgrimage in the same year and was able to convince the architect to travel with him. The Islamic historian Ibn Chaldūn has an eyewitness in his book Ibn Khaldun: Histoire des Berbères (Vol. II) report that “ Abu Eshaq Es-Saheli al-Touwaidjin was a man who was very skilled in several professions and who was drawn from all sources of his talent by building monuments with materials and colors unknown to the region that delighted the king. “The German Africa explorer , historian and Timbuktu traveler Heinrich Barth, however, reported that he had noted an inscription above the main gate that was still recognizable at the time and mentioned the year 1327 and the name of Mansa Moussas .

In the absence of (written) sources, the question must remain open today whether the mosque had a previous building before the years 1325/27. The chronological order of the individual construction phases was controversial until the very end, so Raymond Mauny takes the view that in the western part of the mosque, in the structure close to the mihrāb, the oldest foundations could be determined. Opposing opinions see contradictions in this statement due to the unity of the individual components. To clarify whether original components are still available today, 14 carbon dating studies would be necessary.

An extended reconstruction is said to be due to Qādī Al-Aqib, who completed the building in 1569/70. Further construction work took place in 1678, 1709 and 1736. During this time, the Djinger-ber mosque received three inner courtyards and two minarets. In 1990 it was first put on the Red List of World Heritage in Danger.

architecture

The mosque is not only the oldest, but also the most important in the city. It is a courtyard mosque in the typical architectural style of the Middle iger region. With a trapezoidal floor plan, the entire system covers an area of 3200 square meters, with dimensions of 35 meters (south wall), 52 meters (east), 40 meters (north) and 44 meters (west). The large half of this is accounted for by the inner surface of the prayer room building, which is a pronounced transverse system. The 9 meter high, cone-shaped, pointed mihrāb tower is eccentric and has a minbar corner on the side .

The ceiling above the qibla wall is raised in the mihrāb area. Above the roof terrace, the window opening (with a carved wooden frame) serves as a structure for ventilation and lighting of the mihrāb. Branch wood is used throughout the tower. An ostrich egg forms the top of the tower. The outer facades are structured by different widths and thicknesses of the walls. The cubic battlements and height structures by pilaster strips are striking . All four entrances to the prayer room have frames, some of which are carved, and wooden doors. The interior of the complex facility has nine transverse ships . The mosque also has two courtyards of different sizes, a small one in the north and a larger one on the west side of the complex. The courtyard on the west side of the Betraum building immediately catches the eye with its uneven ground relief, the cause of which is regular sand drifts. Access to the roof and further to the minaret of the mosque is possible from the northern courtyard. The gallery is partially without a roof. The minaret is shaped like a truncated pyramid and is 15 meters high. A cone-shaped tip is placed on the tower terrace.

The condition of the mosque at the beginning of the 1980s was characterized by progressive weathering on all external facades. The stairs to the roof had collapsed, or at least in disrepair. The facing masonry consists of limestone ( diatomite ) and clay mortar on the east facade. A note in Leo Frobenius' field sketch (August 1908) erroneously indicated that the facing masonry was made from salt stones that had been obtained from camels and under costly conditions from the salt mines of Taudeni. The mihrāb tower also showed severe weathering. Therefore, since December 1996 restorations have been carried out as part of the “Safeguard Project” (UNESCO).

Sankore Mosque

Supplementary building history

In the Sankóre ( Songhai : White Masters ) district of the same name , on the northern edge of the traditional city of Timbuktu, is the Sankóre Mosque. The mosque was built during the Mali Empire. Construction is expected to begin shortly after the Djinger-ber mosque was built. Qādī Al-aqib, who is said to have also laid hands on the Djinger-ber mosque, restored the mosque between 1578 and 1582, after the previous building was probably destroyed.

architecture

With a total area of 1180 square meters, it is smaller than the Djinger-ber Mosque, with dimensions of 31 meters (south wall), 28 meters (east), 31 meters (north and west). The walls encompass an inner courtyard of 13 m². The mosque is considered a prototype of Islamic buildings in sub-Saharan Africa . It has a pyramidal minaret with a height of 14 meters. The mosque is said to have housed the center of Islamic teaching for the region.

Qādī Al-aqib is said to have measured the Kaaba with cords in Mecca and laid these cords to form the floor plan of the inner courtyard of the Sankóre Mosque in order to transfer the external dimensions of the Islamic sanctuary (actual area 11.03 mx 12.62 m) to Timbuktu . In 1678 the minaret collapsed. Construction work took place in 1709/10 and 1732 and in the 1900s (especially 1908). In the interior, dilapidated arcades were replaced by simple but very durable joist beams. In 1952 the mosque roof was raised and the east side covered in the following years after it was found that the sand had reached the roof of the mosque, that it had been blown up and the walls of the mosque interior had been destroyed. It became apparent that the east facade of the mosque was last covered with limestone. Nowadays it is impossible to enter the mosque from the west.

It is also a courtyard mosque. She only has one yard. This is located as an inner courtyard in the center of the facility. The minaret is on the south side. On the east side, the roof of the mosque can be climbed via a single flight of stairs. The prayer room building is based on an irregular floor plan. Here, too, the mihrāb tower is eccentric. The once sugar-loaf-shaped tower is now cylindrical, step-shaped. It has stone cladding and the entablature is made of thick billets. The facade structure of the eastern outer wall shows extensive pilaster strips and cubic battlements with a pyramid-shaped tip. The wooden doors have metal fittings in the Moorish style. The interior of the building is characterized by four transverse naves, clearly highlighted in the first two naves. The mihrāb has a rectangular base and ends horizontally. there is also a horizontal niche above. The beam ceiling consists of Borassus trunks. The minaret has the shape of a composite truncated pyramid with a broad base. Small corner battlements decorate the parapet of the roof terrace.

Columns inside the mosque separate the winter from the summer prayer room. According to the Tarik-el-Fettach Chronicle, the northern part of the mosque is said to have been available to students as a university (Sankoré University). The rapid silting up of the premises was a permanent problem for the building . Although the mosque has only minor traces of erosion on the external facades and only minor damage can be attested to in the facing masonry, its decay can be clearly seen on the west side of the mosque (from the inside) . The Malian Ministry of Culture therefore financed the renovation in cooperation with the Cultural Mission for Timbuktu and the mosque administration committee. In 1996 the UNESCO World Heritage Center took on the further protection of this mosque.

Sidi Yahia Mosque

Supplementary building history

The Sidi Yahia Mosque is located in downtown Timbuktu. Residential areas adjoin from three directions. It is the best preserved mosque in the city and is said to be traced back to Marabout Muhammad Naddi (Sheik El Mokhtar Hamalla) at the beginning of the Tuareg rule (1432 to 1468), the name being given to his friend, the Imam Sidi-Yahya (Sidi Yéhia El Tadlissi ) goes back. Muhammad Naddi and Sidi-Yahya are said to be buried in the east wing of the mosque. From 1577–1578 the sanctuary was restored by Elhadj El-Aqib, who was also responsible for later construction work on the two aforementioned mosques. In 1939, the tin tower of the minaret was rebuilt and the portal gates were redesigned in the shape of a pointed arch . In the same year, the entire system was faced with limestone (diatomite). The mosque has three rows of columns in the winter prayer rooms. There is also a courtyard for the summer prayers. In 1989 the Sidi Yahia Mosque was also placed on the Red List of World Cultural Heritage in Danger as part of the “Safeguard of the Timbuktu Mosques” project.

architecture

The entire facility extends over an area of 1460 square meters. The mosque is a court mosque based on the Middle Ages model. The courtyard itself has an irregular floor plan because it is restricted on the southeast side by natural obstacles. A striking feature in the courtyard is an old population of trees with desert dates along the long sides of the mosque. The cylindrical- stepped mihrāb tower measures 5.8 meters high, the minaret, equipped with cubic battlements , 8.6 meters. The courtyard wall is over 2 meters high. The southern part of the wall extends over a length of 30 meters. In the east as in the north it is 31 meters long and in the west 30 meters. In 1939 the mosque was completely renovated by French architects, using solid clay, so-called Timbuktu stone . As a specially processed material, this stone was only used locally in architecture, but not in other cities in the region. The prayer room building is designed as a transverse system. The entrances are secured by wooden doors with decorative metal fittings. The interior of the mosque is divided by four transversal aisles, the passages are rectangular. A chandelier hangs in the first ship .

Destruction by Islamists in 2012

In early May 2012, the Islamist West African group Ansar Dine destroyed the Sidi Mahmud Ben Amar mausoleum in Timbuktu, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and threatened attacks on other mausoleums. At the end of June 2012, Timbuktu was placed on the Red List of World Heritage in Danger due to the armed conflict in Mali . Shortly afterwards, the destruction of the UNESCO- protected tombs continued under mockery of UNESCO, this time the Sidi Moctar and Alpha Moyaunter were affected . In January 2013, at the request of the Mali government, France intervened militarily and liberated Timbuktu (→ Opération Serval ). By the end of January 2013, it was possible to push back the Islamist groups from all major cities in the region, including Timbuktu. The conflict in northern Mali , however, continued.

In August 2016, it became known that one of the defendants allegedly destroyed nine tombs and the Sidi Yahia Mosque in 2012 , whereupon he was sentenced to nine years in prison.

See also

Notes on the historical sources of the Tarikhs

- Tarikh el-Fettach : Translated: Book of Seekers . A native historical work in Arabic that was created in the 17th century. The work, which goes back to Mahmud Kati and Ibn al-Mochtar, describes the history of the Tekrur people (cf. Tukulor ) and the Songhaire Empire . Translated to this day in a valid version by the French ethnographer Maurice Delafosse , known for his major work Haut-Sénégal-Niger (1912) .

- Tarikh as-Sudan : Translated: Book of Sudan . The historical work of Abderrahmane Es Saâdi from Timbuktu, written in Arabic and written in the 17th century. Translated in the current version by Maurice Delafosse (see above).

literature

- Leo Africanus : Jean-Léon l'Africain, description de l'Afrique, trad. Par A. Epaulard, Paris 1956 , in Giovan Battista Ramusio (ed.): Primo volume, et Seconda editione delle Navigationi et Viaggi. Venice 1550.

- Abū ʿUbaid al-Bakrī : Al-Bakri (Cordue 1068), Routier de l'Afrique blanche et noire du Nord-Ouest, trad. Nouvelle Avec notes et commentaire par Vincent Monteil , in Bulletin de l'IFAN 30, sér. B, 1 (1968), p. 39 ff.

- Heinrich Barth : Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa in the years 1849–1855 , 5 volumes, Gotha 1855–1858 (reprint Saarbrücken 2005), volume 1, ISBN 3-927688-24-X , volume 2, ISBN 3-927688 -26-6 , Volume 3, ISBN 3-927688-27-4 , Volume 4, ISBN 3-927688-28-2 , Volume 5, ISBN 3-927688-29-0 . Short version as: In the saddle through North and Central Africa. 1849-1855 . Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-86503-253-2 .

- Rudolf Fischer: Gold, salt and slaves: the history of the great Sudan empires Gana, Mali, Songhai . Stuttgart (Tübingen), Edition Erdmann, 1986 (1982). ISBN 3-52265-010-7 (3-88639-528-6).

- Leo Frobenius : The Unknown Africa. Illumination of the fate of a continent . in series: Publication by the Research Institute for Cultural Morphology , Munich, CH Becksche Verlagbuchhandlung 1923.

- Dorothee Gruner: The clay mosque on the Niger, documentation of a traditional building type , Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart, 1990, ISBN 3-515-05357-3 .

- Bernd Ingmar Gutberlet: The new world wonders: In 20 buildings through world history , Lübbe (2010), ISBN 978-3-8387-0906-2 .

- John O. Hunwick: Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613 and other Contemporary Documents , Brill, 1999.

- John O. Hunwick: Sharīʿa in Songhay: the replies of al-Maghīlī to the questions of Askia al-Ḥājj Muḥammad . Union Académique Internationale Fontes Historiae Africanae / Series Arabica V. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1985, ISBN 0-19-726032-2 .

- Peter Lenke: Timbuktu as a center of African learning in the course of history , ISBN 978-3-640-13545-5 .

- Nehemia Levtzion (ed.), JFP Hopkins (transl.): Corpus of early Arabic sources for West African history . Cambridge [u. a.], Univ. Press, 1981; Princeton reprint, 2000, ISBN 0-521-22422-5 .

- Raymond Mauny: Notes d'archéologie sur Tombouctou . Bulletin IFAN 3 (Dakar), 1952: pp. 899-918.

- Chris Scarre : The Seventy Wonders of the World. The most mysterious buildings of mankind and how they were built , 3rd edition, 2006, Frederking & Thaler, ISBN 3-89405-524-3 .

Web links

- The mosques in Timbuktu

- Is the destruction of world heritage a war crime?

- Timbuktu, Mali Mali, West Africa

Remarks

- ↑ Tombouctou la Mystérieuse

- ↑ UNESCO: World Heritage List / Mali / Timbuktu

- ↑ .. Nehemiah Levtzion, JFP Hopkins, Ed and Translator (1981): Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History . Cambridge, Revised Princeton, NJ, 2000. pp. 79-80.

- ^ Al Bakri, Routier de l'Afrique blanche et noire du Nord-Ouest. (see lit.)

- ↑ Rudolf Fischer, p. 95 (see lit.)

- ↑ a b c Chris Scarre : The Seventy Wonders of the World, The most mysterious buildings of mankind and how they were erected , pp. 143-145 (see LIT.)

- ↑ Here it is assumed that he was a real historical person.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Fischer, pp. 197–199 (see lit.)

- ↑ The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Written by Al-Hassan ibn-Mohammed Al-Wegaz Al-Fazi, a moor, bapticed as Giovanne Leone, but better known as Leo Africanus. Done into English in the year 1600 by John Pory . Ed. V. Robert Brown. (The Hakluyt Society) London 1896, 3 vols. - (For a long time the authoritative scientific edition)

- ↑ a b c d Rudolf Fischer, p. 201 f. (see lit.)

- ↑ a b c d John O. Hunwick: Sharīʿa in Songhay: The Replies of Al-Maghīlī to the questions of Askia Al-Ḥājj Muḥammad , pp. 9 and 19 f.

- ↑ John O. Hunwick: Timbuktu & the Songhay Empire , p. 81. According to information from Tarikh as-Sudan (ibid.), It was not an isolated case.

- ↑ Timbuktu archicultural heritage and the Cultural Mission experience of participatory Management (Ali Ould Sidi) ( Memento of the original of September 30, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Institut des Hautes Etudes et de Recherches Islamiques Ahmed Baba (IHERI-AB) / Website Tombouctou Manuscripts (IHERI-AB)

- ↑ Saving the Timbuktu Manuscripts ( Memento of October 15, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ John O. Hunwick: "The Islamic Manuscript Heritage of Timbuktu".

- ↑ Dorothee Gruner, Die Lehmmoschee am Niger , p. 64 (see lit.)

- ↑ ICOMOS: World Heritage Criteria

- ↑ Assuming that at the time a mitqal was worth 15 FF, the worshipers were donating approx. 7500 FF per year, i. e. approx. 750,000 FCFA

- ↑ Rudolf Fischer, p. 107 f. (see lit.)

- ↑ a b c d Heinrich Barth, Reisen und Entdeckungen in Nord- und Central-Afrika in the years 1849–1855, Volume 4, p. 486 ff. (See Lit.)

- ↑ a b c d e Raymond Mauny, Notes d'archéologie sur Tombouctou, pp. 901–905 (see lit.)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Dorothee Gruner, Die Lehmmoschee am Niger , p. 298 ff. (See lit.)

- ↑ a b Leo Frobenius, Das unbekannte Afrika , pp. 112–114 (see lit.)

- ↑ preferred suppliers of wood for trunks, branches and twigs are the doum palm, the desert date , the anogeissus leiocarpa and the anabaum

- ↑ Or: alhor (translation of this term wanted)

- ↑ Photo of the mosque (for comparison)

- ↑ According to the Trakh Es-Soudan, this Mohamed Naddi, the Timbuktu koy, chief of the city, constructed the Mosque for his friend Sherif Sidi Yéhia and appoints him Imam in 1440

- ↑ According to Kati, author of Fettach, at that time Mohamed was chief of the village and called Sidi Yéhia in 1440 to highlight the town's cultural and religious prestige: he became fond of him and treated him with the greatest honors

- ↑ Defiant Mali Islamists pursue wrecking of Timbuktu

- ↑ "Timbuktu is in shock": Fundamentalists destroy UNESCO World Heritage Site in northern Mali , NZZ, May 6, 2012. Accessed July 5, 2012

- ↑ Mali Islamists attack UNESCO holy site in Timbuktu , Reuters, May 6, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012

- ↑ Devastated World Heritage Site in Mali: Islamists Mock Unesco Spiegel Online, July 1, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012

- ^ Entry into the civil war: French troops fight in Mali

- ↑ Militant Islamists in Mali, Algeria, Mauritania and Niger (SPON, January 17, 2013)

- ↑ Islamist admits destruction of world cultural heritage sites in Mali , in: Der Spiegel, August 22, 2016.

- ^ Nine years imprisonment for the destruction of world cultural heritage in Mali , in: RP online, September 27, 2016.

- ↑ Tarikh el-Fettach

- ↑ Tarikh as-Sudan