Aerial combat maneuvers

Air combat maneuvers are flight maneuvers that are used in air combat . They were created during the First World War and have since been further developed in line with the technical progress of aircraft . The purpose of a dogfight maneuver is to get into a favorable attack position for another aircraft or in a favorable position to flee. The aerodynamic and engine limitations of the respective aircraft are reached. The resulting flight figures are demonstrated as aerobatics in peacetime .

General

The most favorable position for an attack by a fighter aircraft with forward-facing weapons or missiles is primarily an attack from a position behind the enemy. Such an attack has several advantages:

- In the case of aircraft without rear gunner, the attacking aircraft can approach the enemy without being noticed.

- If the attacking aircraft is not significantly faster than the target, this offers the possibility of shooting at the target over a longer period of time.

- In the case of fighter planes that are under fire, the attacker has the option, as long as his plane is equally manoeuvrable or more manoeuvrable, to press the opponent for a long time in curve combat and thus make a counterstrike more difficult.

Attacks from a significantly elevated position are just as cheap, especially if they are flown from the direction of the sun. Due to the elevated position, it is hardly possible for the enemy to attack, because most fighter planes cannot climb quickly enough without aids to be able to pursue the higher-flying aircraft. On the other hand, aircraft flying lower down can easily be attacked from an elevated position because they have practically no opportunity to defend themselves, especially when attacked from the sun, and the attacking machine also picks up enough speed through the dive to quickly gain sufficient distance after the attack .

A frontal attack is a rather unfavorable maneuver, especially when fighting against fighter planes. Both machines head towards each other. In a fight between fighter planes, both sides theoretically have the same opportunity to shoot down the enemy, which is why this maneuver is not advantageous under such conditions. When fighting heavy bombers (such as B-17 ), on the other hand, the maneuver had the advantage over the attack from behind that the front attacking fighter could fire the large bomber quite well, while the gunner had difficulties with the small one Target fighter aircraft at an approach speed of around 900 to 1000 km / h. This maneuver was used by the Luftwaffe as standard against the Allied bomber formations towards the end of World War II. In the event of an attack from behind, however, the gunner could easily have fired at the fighter.

In some publications this is referred to as the "fight for the angle" , meaning the angle between the longitudinal axis of the aircraft of the attacker and that of the defender. If you succeed in reducing this angle, the shooting position will be better. A large angle requires a large amount of lead angle when firing the on-board weapons, which means that the hit rate is low.

While tight curve combat still dominated in World War I and success largely depended on mastering the aerodynamics on the wing, during World War II the enormously improved drives and thus speed and climbing power for air combat tactics came to the fore. The faster aircraft has the advantage of choosing the attack position and converting the kinetic energy (speed) into potential energy ( flight altitude ) over and over again. Improved flight performance and higher flight speeds also increased the G load on the pilot when changing direction , which from then on represented a limiting factor.

This trend continued with the continuously improved drive systems. Modern combat aircraft can structurally withstand a load factor of up to 12 g (12 times the acceleration due to gravity), and with optimal training conditions, a short-term load of a maximum of 9 g is still bearable for humans.

Due to the use of radar , targeting missiles and computer-aided weapons control systems, air combat maneuvers play a subordinate role in modern air warfare.

Attack maneuvers

- Hit and climb : The opponent is attacked from cant, the excess energy is converted back to cant by a steep climb. The maneuver can be repeated as long as there is excess energy.

- Hit and run : The enemy is attacked with excess speed, the excess energy is used to bring distance between you and the enemy in order to prepare a new attack from a safe distance.

- With Immelmann , even Immelmann turn or recovery , called an aerobatic maneuver is described consisting of a half loop and a subsequent half role is. Half of the loop is flown from the horizontal rising up to the supine position. This is followed by half a roll to get back to normal. With the Immelmann , the flight direction can be reversed quickly and in a confined space. This maneuver is no stall flown.

- Hammerhead or military wing-over : Connects to a "hit and climb" maneuver, whereby the climb has a climb angle of about 70 degrees and is continued until the stall . The resulting, jerky downward change of direction enables the on-board weapons to be fired at the enemy if the enemy tried to follow the climb.

Defensive maneuvers

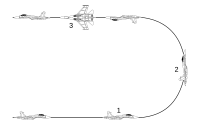

- Scissors : "scissors cutter", horizontal changes of direction with the purpose of causing the attacker to "overshoot" and thereby increase the angle of attack.

- Split-S : Half roll, half looping (downswing), makes it difficult for the opponent approaching with excessive speed to get into the shooting position, only possible at a certain distance from the ground.

The list can be continued by e.g. B. high yoyo , low yoyo , hugger split-S etc.