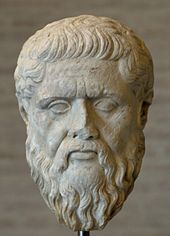

Lysis (Plato)

The Lysis ( ancient Greek Λύσις Lýsis ) is a work of the Greek philosopher Plato written in dialogue form . The content is a fictional, literary conversation. Plato's teacher Socrates discussed with the boys Lysis and Menexenus . Also present are the somewhat older youngsters Hippothales and Ktesippos.

The theme of the dialogue is friendship - especially erotic friendship - and in general desiring love. In addition to érōs , Plato also uses the term philía , which usually denotes a gentle affection or friendship that is not associated with desire. In the homoerotic milieu in which the interlocutors move, it is about same-sex attraction, whereby men, young people or boys can be involved. It discusses the need underlying such attraction, what the desire ultimately aims at, what types of people friendship is possible between, and how love is related to ethics. Socrates, who appears as an expert in the field of eroticism, puts a broad understanding of philia up for discussion, which includes not only friendships and love relationships, but also one-sided love. “Friend” or “lover” is therefore also someone who desires erotically without his love being returned. However, this view proves to be problematic. The tricky question is whether you love what you already have or what you lack; both assumptions lead to trouble. The desired clarification of the requirements for friendship and erotic attraction does not succeed, but the dialogue ends in aporia (perplexity).

The lysis forms the starting point for dealing with the friendship issue in Western philosophy.

Place, time and participants

The place of the dialogue is the changing area of a newly built Palaistra , a practice area for wrestling matches within a high school . At that time the grammar schools served primarily for physical training; In addition, a Palaistra was also a social meeting place for young people. According to Plato, this exercise and meeting place was on an enclosed property opposite the outside of the city wall of Athens .

A chronological classification of the dialogue action is hardly possible because there are no concrete clues. In 469 BC Socrates, who was born in BC, describes himself as an old man when talking to schoolchildren, but this is not necessarily to be taken literally. Debra Nails believes that she can deduce from the presumed biographical data of the interlocutors that probably around 409 BC. Is to be thought of. At that time, however, Athens was in the Peloponnesian War , which does not go well with the mention of the new construction of a sports facility outside the city walls. This construction project seems to point to a time of peace. It can only be about the time of the Nicias Peace, which lasted from 421 to 414. Michael Bordt thinks it plausible to set the fictitious date of the dialogue in the final phase of the peacetime, between approx. 417 and 414. It is spring, the youth are celebrating the Hermaia , the school festival of Hermes , who is venerated as the patron god of the high schools .

The philosophical discussion takes place only between Socrates, Lysis and Menexenus, Ktesippus and Hippothales stay out. Socrates gets the conversation going and directs - as in many of Plato's dialogues - the course of the investigation. He wants to show the youth how to discuss philosophically and show Hippothales how to deal with an erotically desired person. In doing so, he adjusts to the boys' world of experience, adapts to their way of thinking and feeling and selects examples from their area of experience. In the gymnasium he is in his element, since he is very interested in pedagogy and also tends to have a violent erotic desire, especially aimed at beautiful young people, which he always has under control. In contrast to other dialogues, in which Socrates acts cautiously and encourages his interlocutors to develop their own insights in the spirit of Maieutik , here he brings the further thoughts directly into view. To what extent the historical Socrates thought and argued like Plato's dialogue figure, however, remains open. In addition, Plato's Socrates only puts various theses up for discussion without identifying with them.

Lysis and his best friend Menexenos are believed to be around thirteen years old, while Hippothales and Ktesippos are believed to be around three years older. A pronounced interest in homoerotic relationships is already noticeable among adolescents, which is taken for granted in the high school environment and gives rise to teasing. Hippothales is madly in love with Lysis. The starting point of the discussion about love for friends is thus a personal concern, the topic has a strong relation to the reality of life of those involved. Socrates is aware of the complex emotional relationships and needs and uses them for his didactic purposes.

Lysis, the son of Democrats, is a historical person; his gravestone, on which he is depicted, was discovered in 1974. To distinguish it from his grandfather of the same name, he is also called Lysis II in the research literature . It came from the Aixone demos . His family was rich and respected; his ancestors were famous horse breeders who had won victories in horse races. In the Lysis he is portrayed as exceptionally handsome, reserved, and mentally capable; philosophically he is clearly more gifted than Menexenus. Menexenos is also a real person. The historical Menexenus was a pupil of Socrates. He also came from a noble family; his ancestors had held political leadership positions. Plato also allows him to appear as Socrates' interlocutor in the Menexenos dialogue named after him ; there he's already grown up. In Lysis he is described as a contentious disputer, but his good behavior in conversation does not correspond to this. There is no reliable evidence for the existence of Ktesippos and Hippothales, but they are also considered historical. Ktesippos from the Demos Paiania was a relative of Menexenus and like him a pupil of Socrates. Both were 399 BC Present at the death of Socrates. Ktesippus also appears in Plato's dialogue Euthydemos ; he is older there and vigorously intervenes in the debate. Hippothales is probably not the philosopher of the same name whom Diogenes Laertios mentions among the disciples of Plato. In Lysis Hippothales is described as shy and embarrassed; he is ashamed to admit that he is in love with Socrates. Since Lysis does not seem to reciprocate his inclination, he behaves very cautiously.

content

The introductory talk

Socrates, as the narrator, reports how the dialogue went. According to his description, one day he came across a group of boys, including Hippothales and Ktesippos, at the city wall. Hippothales invited him to come to the nearby Palaistra. Socrates did not yet know this sports complex because it was newly built. Hippothales attracted him with the opportunity to meet many beautiful youths there. Socrates then asked who, for Hippothales, was “the” beautiful - the erotically desired one. Hippothales blushed, was embarrassed, and did not answer. Then Ktesippus interfered; he revealed that Hippothales was in love with Lysis. He also reported that the lover kept talking about Lysis, praising his glorious ancestors in poems, writings and songs, and pestering those around him with this obsession.

In addition, Socrates noted that when courting someone, it was unwise for various reasons to glorify them. That would only scare him away like a hunter who scares off game; in case of failure, be embarrassed and, moreover, fill the beloved with conceit and arrogance. The more haughty someone is, the harder it is to win them over. Hippothales admitted this and asked for instruction on how to do better. Socrates was happy to demonstrate this to him as an example. Together the group went to the Palaistra. There they met the strikingly handsome Lysis and his best friend Menexenos in the crowd. While Hippothales hid in the crowd to listen without being seen by Lysis, Socrates began the conversation with the two boys, the course of which he describes below.

The basis of appreciation and attractiveness

At first Socrates asks about the boys' self-assessment and their friendly rivalry, but Menexenos is called away. Now, with Lysis, Socrates tries to clarify in an age-appropriate way what is involved with loving or liking (phileín) , the activity belonging to the term philia (friendship, love). Love, he says, is based on appreciation. The able is valued and loved for the sake of their abilities. Nobody is attractive for their weaknesses, but a person appears lovable only because of their merits; one loves about it what one considers good and useful. Understanding, judgment or competence play a key role among the advantages that come into consideration here. It instills respect, trust, affection and friendship to those who own it. The ignoramus, on the other hand, is considered inept and useless, not even his relatives appreciate him. The hierarchy according to knowledge is also shown in the decision-making powers: the more competent someone is, the more room for maneuver they are granted. For example, children are only allowed to do what adults believe they are capable of. Those who are considered competent are popular and also powerful; he makes decisions and his instructions are willingly followed. One likes to be friends with him.

So you can only make friends if you become capable by acquiring knowledge. Lysis has to realize that he has not made it very far because he is still a school child. With this train of thought, Socrates leads him to modesty and a thirst for knowledge instead of - like Hippothales with his praises - to arrogance and complacency. Lysis asks the philosopher to explain what has been said so far to Menexenus, who has since returned.

Mutual and one-sided love

Since Menexenos and Lysis are friends, Socrates turns to Menexenos, who is now experienced in the field of friendship. He wants to hear from the boy how to become a friend and what the term phílos (friend, lover) actually means. The word has a double meaning in Greek: "loving" and "dear". It can denote both the lover and the beloved. The question to Menexenos is whether both are equally “friends” or whether only the lover or only the beloved in the real sense should be called philos . Menexenos sees no difference, he opts for the first option. But Socrates wants to get down to the problem of one-sided love. He asks whether you can only call someone a friend or lover when he loves and his love is reciprocated, or whether you are philos when you love one-sidedly. When it comes to one-sided love, Socrates thinks of the asymmetrical structure typical of homoeroticism at the time, whereby a somewhat older lover (erastḗs) woos a younger lover (erṓmenos) and in some cases remains unsuccessful. The lover is regularly the active and passionate partner, the lover the passive and rather sober one. Even if the lover accepts the advertisement, they usually do not fall in love.

Menexenos thinks that philia must be mutual. Socrates refutes this with counterexamples. He makes use of the fact that the term philos is not only used in the context of friendships between people, but also in positive affective relationships of all kinds; it is also used when it comes to loving or liking things, activities or qualities. In these cases the one-sidedness is obvious: one can be a horse lover or a sports enthusiast or a lover of wine or wisdom, although one is not loved by the object of such philia . Parenthood provides another counterexample: parents are friends of their children even if they are not loved by them, for example if the child is a toddler who cannot yet love, or if a child has been punished and therefore hates the parents . Accordingly, the lover is always the friend or lover, regardless of whether he is loved or hated by the person he loves. However, this leads to the paradoxical conclusion that one can be a friend of one's enemies and an enemy of one's friends. One cannot escape the paradox even if instead of the lover one defines the beloved as the philos ; he can then be a friend of people he hates or by whom he is hated. Accordingly, all attempts to define the term have failed; they fail partly because of an empirical refutation, partly because of absurd consequences.

The role of equality and diversity, goodness and badness

After the investigation has reached a dead end, Socrates tries a different approach. He turns back to Lysis and chooses as a new starting point Homer's statement that a god always leads “the same to the same”. According to Socrates, this statement agrees with the statements of natural philosophers who consider it necessary that like with like always be friends. That seems to be only half true, however: while good people are friends with good people, bad people are not bad people. Malice or wickedness means doing wrong. Thus, if the wicked are alike, they must, according to their nature, harm one another and treat one another as enemies. According to this consideration, like can be enemies of like. In reality, however, this is not the case, for the premise of the conclusion is erroneous: the wicked are not the same, but each of them is different. The evil one is not even equal to himself - that is, uniform and constant in his essence - but is divided, unstable and unpredictable. Hence, the wicked cannot be friends with anyone. It follows that only good people can be friends. Lysis agrees with this result.

But now a new problem immediately arises. You have appreciation for what you need. You love what you want and what you expect an advantage from. Everything desired is desirable because of its advantages, because of what it is intended to bring to the desire. Therefore, similar things are not attractive, because they show what you already have. The good person already has goodness and can be satisfied with this possession. Since he is self-sufficient, he does not need the goodness of others; it cannot enrich him. Therefore the good person has no reason to befriend other good people. Since he already has their privilege himself, their presence does not bring him any gain, nor does he miss them when they are absent. Socrates develops this line of thought still further, referring to Hesiod . He now even claims that love can only exist on the basis of opposites, because everything needs the quality of the opposites. The poor need the rich, the weak need the strong, the ignorant need the knowing. Only opposites offer nourishment, the same is useless.

Menexenus is impressed by this consideration, but Socrates immediately points out the paradoxical consequences. For example, if all opposites were attracted, there should be an attraction between good and bad, just and unjust, and friendship should give friends a tendency to become enemies. Since this is not the case, it cannot be opposites that make something desirable.

This begs the question of how friendship is possible at all. It has been shown that good cannot be friends with either good or evil, and evil cannot be friends in principle. However, some things cannot be assigned to either the purely good or the purely bad area, but are in between. This “neither good nor bad” is exposed to influences from both sides. It cannot be friends with what is of its own kind, since this would not earn it anything. Thus, there is only one possible combination left for friendship: The “neither good nor bad” can be friends with the good, because it wants to free itself from the harmful influence of the bad and therefore strives for its opposite. It is for this reason that he develops a desire for good unless he succumbs entirely to the bad influence. For example, the wise man (sophós) does not practice philosophy (literally "love of wisdom") because he does not need it, and bad people do not philosophize because this activity offers them no incentive and their ignorance is hidden from them. All philosophers belong to the intermediate realm of “neither good nor bad”; they are lovers of the wisdom which they lack and the lack of which is known to them.

The purpose of desiring love

Socrates soon put an end to the joy of the apparently found solution, because he encountered new problems. Friendship is not an end in itself, but a friend or lover of something because it seems to promise a profit. One wants to get something good through friendship and escape from something bad. For example, the patient's attitude towards the doctor is friendly because he wants to get well. Health is the purpose of the friendly relationship between them. The patient is a friend of the doctor and the art of healing because he is a lover of health. So he has philia - desiring love - for health. But this raises the question of the purpose of this philia : Health is also not striven for for its own sake, but because it is needed for something else. This is how one arrives at an infinite regress : Behind every friendship, desire or love there is a purpose that is striven for, and this is actually where desiring love is directed. But this end is also there for the sake of a benefit; a new, overriding purpose must emerge behind it.

Progressing from one purpose to the other leads to infinity if the search never reaches its goal. Therefore, at the end of the chain of objects of desire, there must be a “first beloved” or “first love” (prṓton phílon) that has no purpose but is loved for its own sake. In addition, this consideration shows that there can be a philia in the real sense only for the "first beloved", because all other objects of desire turn out to be a means to the respective end, but means are in and of themselves - apart from the goal - not attractive, but indifferent. So whatever is usually taken to be friendship or love is tentative and conditioned and as such is an illusion. The seeker is always looking for that which brings him closer to his actual goal, the “first lover”. Socrates calls this goal “ the good ”. What is meant is that good behind which there is nothing better for the seeker, with which the search must end. It is the only real object of any philia .

The cause of desiring love

Another problem that Socrates now draws attention to arises from the polarity of good and bad, which form a pair of opposites. If the appreciation of the good and the pursuit of it are based solely on the desire to escape from the bad, then with a complete elimination of all influences of the bad, the attractiveness of the good should at the same time disappear. The “neither good nor bad” would be freed from all tribulations and would then no longer have any reason to strive for the good. Accordingly, the elimination of the bad would result in the fall of love for the good, the abolition of the only true philia . If this were true, there could be philia only because and as long as there are bad influences. Then the power of the bad would be a prerequisite for every desire and every love. But it cannot be like that, for there are also desires that are neither good nor bad and therefore would outlast the removal of the influences of the bad. Thus there is a philia that cannot be explained as an escape from the bad. This means that loving and being loved cannot be traced back to the contrast between good and bad, but must have a different cause.

What is certain, as Socrates explains, is that the lover desires what he lacks. This is something that actually belongs to him, but is currently withdrawn from him, which is why he suffers from a deficiency. According to this, one can determine the lack of one's own or “belonging” (oikeíon) of the lover as that which every desiring love aims at. Then friends are really relatives, they belong together by nature. According to this understanding, the very presence of desiring love proves that the lover and the object of his desire are meant to be one another if the love is real and not just fake. Then this love must also be reciprocated by the beloved. Lysis and Menexenus are reluctant to agree to Socrates' assertion. Lysis in particular does not like it, because the consequences for his relationship with Hippothales are obviously undesirable to him. The Hippothales, who is secretly listening, is thrilled.

However, Socrates shows that this path does not lead to the solution of the problem either. When the loved one is identified with the like, the objection set out earlier arises that refutes the concept of love of like for like. If there is something belonging to the bad, there must also be friendship among the bad, but this has already been found impossible. This contradiction can be avoided by equating what is relative with what is good, but that means that good is loved by good - an assumption that was refuted earlier.

Thus the dialogue has led into an aporia. The attempt to determine the conditions for desiring love has failed for the time being. Socrates realizes that there is perplexity. He would like to continue the quest for knowledge and include one of the older youth in the discussion. But it is getting late, the children have to go home. Finally, Socrates points out that if you claim to be a friend but you don't know what it is, you are ridiculous.

Philosophical balance sheet

The dialogue ends aporetically, as it does not succeed in clarifying the questions raised, but not without result, because certain assumptions that are usually not questioned have proven to be unsound. The research has shown that the current understanding of friendship and love is questionable. In the real sense, according to the findings of the discussion , philia only exists in the relationship between the absolutely good and that which is between good and bad and strives for the good. It is thus not a mutual relationship between two lovers of equal rank, but an asymmetrical relationship between a desiring person and a metaphysical , sensory entity . That there must be “the good”, the absolutely unsurpassable good in itself, must be the only true goal of desire, should be shown with the argument that otherwise an infinite regress occurs. This is the first recorded case of such an argument in the history of philosophy.

Plato's critical assessment of the famous poets, who were considered to be wise and whose authority was enormous, is shown in the fact that he has Socrates quote verses by Homer and Hesiod in which the two poets seem to take contrary positions. This is to suggest that it is unwise to uncritically rely on such authorities .

Whether or to what extent Plato's doctrine of ideas is already implicitly present in the Lysis - it is not explicitly thematized - has long been highly controversial in research. It is mainly about the concept of the “first beloved” or “first love” (proton philon) , the actual goal of philia , which is not an end for something else. It is disputed whether this goal can be defined as a Platonic idea - the idea of the good addressed in Dialog Politeia . Gregory Vlastos opposes the "standard interpretation" advocated by many researchers, according to which the "first beloved" is to be equated with this idea and thus to be understood as a metaphysical object . Other possible interpretations are that the “first beloved” can mean eudaimonia - a good, successful lifestyle and the associated state of mind (“bliss”) - or wisdom or virtue. Such conjectures, however, are speculative and require the use of other dialogues by Plato; they cannot be derived from the wording in the lysis . Matthias Baltes suspects that the “first lover” is the idea of friendship. As a justification, he argues that Plato uses terms that refer to the context of ideas, and that the conceptual system also points in this direction. The “first beloved” stands out to a great extent from the other “dear” things whose cause of existence it is; thus it is a metaphysical object. However, his identification with the idea of the good is very problematic. Baltes concludes from this that it is about the philon (the friend, loved, desired) par excellence, i.e. the platonic idea of friendship. Werner Jaeger equates “first love” with the highest value; it is "the meaningful and goal-setting principle of all human community". Some researchers see the Lysis as a text that is intended to prepare the reader for the concept of " Platonic love " presented in Plato's symposium .

An important circumstance for understanding Plato's remarks is that the “first beloved” is the goal, but is not purposefully approached. It is the very object of love or desire of any lover or desire and the explanation for the existence of their needs, but they are usually unaware of it. At the level of consciousness, he strives for preliminary goals that are subordinate to the actual goal he is unconsciously looking for. Ignorance of the true object can - as in the case of the Hippothales - lead to getting on the wrong track.

The views presented in the Lysis on the requirements of the philia are controversial in research. In particular, it concerns the thesis put forward by Plato's Socrates that philia always has the purpose of providing the lover from whom it originates a benefit, and without this purpose it cannot exist. If friendship and other goods are understood to be mere means that are in an exclusively instrumental relationship to their end, i.e. have no value of their own and are not part of the end, one speaks of “ethical instrumentalism”. It is disputed whether Socrates actually identified with an instrumentalist theory of friendship or whether he only brought this point of view into play in order to stimulate the young people to think. In addition, the question arises whether such an “egoistic” understanding of love and friendship corresponds to Plato's conviction. Gregory Vlastos advocates the “selfish” interpretation, according to which Plato's Socrates traces every friendship back to a selfish motive. The opposite view, according to which the real concept of love and friendship from Plato's Socrates contains an "altruistic" component that is important from his point of view, is supported by others. a. Michael D. Roth.

The drafting time

It is almost unanimously accepted in recent research that this is an authentic work by Plato. There is also agreement that the lysis belongs to either the early or the middle creative period of the philosopher. Attempts at a more precise classification have led to a long research debate. The aporetic outcome, the brevity of the text, commonalities with certainly early dialogues and stylistic features are cited as indicators of early development. Scholars who find the dialogue unsatisfactory in terms of literary quality or from a philosophical point of view attribute their assumed weaknesses to the fact that it is a youth work by the inexperienced author. It has even been suggested that Plato still used the script in 399 BC. Written Socrates executed. Other researchers would like to move the lysis closer to Plato's middle creative period or even to attribute it to it. The view that it belongs to the time of transition from the early to the middle dialogues is well received. A draft in the 380s, around the time when Plato founded his academy , is considered relatively plausible , but there is a lack of meaningful reference points.

reception

The Lysis is the first work in the history of Western philosophy devoted to the study of friendship. Although its direct aftermath was relatively modest, as it is overshadowed by more famous works by Plato, it forms the starting point of the occidental discussion of this topic.

Antiquity

Plato's student Aristotle has the lysis known. In dealing with friendship in his writings Eudemian Ethics and Nicomachean Ethics , he dealt with issues that Plato had discussed in the dialogue. He followed up on the considerations in Lysis without naming the work. The Epicurean Kolotes von Lampsakos (* probably around 320 BC) wrote the polemical text Against the 'Lysis' of Plato , which is fragmentarily preserved on papyrus .

Otherwise, the ancient philosophers - including the Platonists - paid little attention to lysis , as its subject matter is treated more productively in other, far more famous works by Plato ( Politeia , Symposium ). Nothing is known of an ancient commentary. However, the dialogue was used in the dispute between the “skeptical” and the “dogmatic” direction of the Plato interpretation. With this difference of opinion, which began in the 3rd century BC The Platonists were concerned with the question of the availability of reliable knowledge. It was disputed whether Plato was skeptical about the possibility of a reliable knowledge of reality or whether he advocated an optimistic epistemology , that is, considered “dogmatic” statements to be legitimate. Skeptics pointed out, among other things, the aporetic character of the lysis in order to underpin their thesis that Plato, in view of the contradictions and uncertainties of the results of philosophical investigations, abstained from a judgment about their truth content.

In the tetralogical order of the works of Plato, which apparently in the 1st century BC Was introduced, the lysis belongs to the fifth tetralogy. The historian of philosophy Diogenes Laertios counted it among the “ Maieutischen ” writings and gave “About friendship” as an alternative title. In doing so, he referred to a now-lost script by the Middle Platonist Thrasyllos . In Diogenes there is also an anecdote, according to which Plato had already written Lysis during Socrates' lifetime and read it to him, whereupon Socrates expressed his displeasure with his pupil by exclaiming: “By Heracles, how much the young man lies about me! “A slightly different variant of this legend can be found in the anonymously handed down late antique“ Prolegomena to the philosophy of Plato ”. There it is alleged that Socrates read the Lysis and then said to his companions: "This young man takes me where he wants, as far as he wants and to whom he wants." The anecdote very probably does not have a historical core, it is in most recently viewed as a free invention.

The ancient text tradition is limited to a small papyrus fragment from the early 3rd century, which, however, offers noteworthy text variants.

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

The oldest surviving medieval Lysis manuscript was made in the year 895 in the Byzantine Empire . Some manuscripts contain scholia ; in the oldest manuscript there are scholias that are traditionally attributed to the famous Byzantine scholar Arethas , but possibly come from a lost late antique model of the Codex . In the Latin-speaking scholars of the West's work in the Middle Ages was unknown.

In the West, the lysis was rediscovered in the age of Renaissance humanism after the Byzantine scholar Manuel Chrysoloras brought a manuscript of the original Greek text to Italy. The humanist Pier Candido Decembrio, who lives in Milan, created the first Latin translation in 1456 at the latest, removing allusions to homoeroticism. Another translation into Latin is by Marsilio Ficino . He published it in Florence in 1484 in the complete edition of his Plato translations. In his introduction (argumentum) to his Latin lysis , Ficino concealed the aporetic character of the dialogue. He wrote that Plato dealt in this work more with the refutation of errors than with the demonstration of the truth, but the philosopher's view can be inferred from the work.

The first edition of the Greek text was published in Venice by Aldo Manuzio in September 1513 as part of the complete edition of Plato's works published by Markos Musuros .

Modern

Classical Studies and Philosophy

In older research, judgments about literary quality and philosophical content were often unfavorable. A number of researchers have denied the lysis a philosophical benefit; It was only in the Symposium , Politeia and Phaedrus dialogues that Plato presented his concept of love. The lysis , if interpreted on its own, is not helpful. It is only of importance as a preliminary exercise for the later masterpieces of the philosopher.

As early as 1804, in the introduction to the first edition of his translation of Lysis , the Plato translator Friedrich Schleiermacher criticized, among other things, “hard transitions, a loose arbitrariness in the connection”; he said that such shortcomings were due to "the inexperience of a beginner". Friedrich Nietzsche rejected the widespread view that it was a youth work. He asserted that Plato's theory of ideas was kept away, but that the solutions were to be found in it. The end of the dialogue was "abrupt and unsatisfactory". The renowned philologist and Plato connoisseur Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff found the Lysis literarily attractive - it shows a " corregiesque style of painting" - but stated that Plato had not yet made his way through this text philosophically to clarity. William KC Guthrie found the dialogue to be a failure from a philosophical point of view insofar as it was intended to demonstrate the application of the Socratic method . However, he judged the literary quality to be favorable.

A thesis that has aroused a lot of offense with modern ethicists is the assertion of Plato's Socrates that all striving for friendship or for an object of love ultimately aims at the “first beloved”. The consequence that the normal affective ties between people are not friendships in the actual sense and that the only true love object is an abstract value is deprecated as an unacceptable devaluation of human friendship and love relationships.

However, numerous scholars have emphatically contradicted the previously common derogatory assessment of the work. In 1944 appreciated Werner Jaeger the Lysis as one of the most graceful of the smaller dialogues; “In a first, bold advance” Plato had advanced to the newly created concept of the “first thing we love”. Thomas Alexander Szlezák attributes the frustration of some interpreters, who judged the work as unsuccessful, to a lack of understanding of the author's intention, who definitely intended this frustration as part of his didactic concept.

In the more recent research literature, a positive assessment has prevailed. Olof Gigon praises individual parts that he characterizes as lovable or masterful, and also considers the philosophical yield to be essential. Francisco J. Gonzalez finds the lysis fascinating and believes that in the discussion of the relationship between the "relative" and the philia it has an independent philosophical content. Michael Bordt assesses the dialogue as exciting and philosophically interesting; however, the “existential depth” only becomes apparent when one undertakes “the arduous work on the text”. Michael Erler sees the Lysis as an important testimony to Platonic philosophy and the art of dialogue. After an in-depth analysis, Terry Penner and Christopher Rowe come to the conclusion that the Lysis should not be seen as a mere draft for one of the later master dialogues, but that it is characterized by its own significant income.

The mystery and special need for interpretation of the lysis is often pointed out; Ernst Heitsch calls it one of the "strangest and most idiosyncratic" dialogues of Plato, perhaps the strangest of all.

Extra-scientific reception

The writer and poet Rudolf Borchardt made a German translation of Lysis , which he published in 1905.

The homosexual French poet Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen had the Villa Lysis built on Capri in 1904–1905 after he had to leave his homeland because of a scandal . With the name of the house he referred to the platonic dialogue and especially to the pederasty themed in it .

The British writer Mary Renault made Lysis one of the main characters in her novel The Last of the Wine Lysis, published in 1956 .

Editions and translations (some with commentary)

- Franco Trabattoni, Stefano Martinelli Tempesta u. a. (Ed.): Platone: Liside . 2 volumes, LED, Milano 2003-2004, ISBN 88-7916-230-6 (Volume 1) and ISBN 88-7916-231-4 (Volume 2) (authoritative critical edition with Italian translation, commentary and research).

- Gunther Eigler (Ed.): Plato: Works in eight volumes. Volume 1, 4th edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-19095-5 , pp. 399–451 (reprint of the critical edition by Alfred Croiset , 4th edition, Paris 1956, with the German translation by Friedrich Schleiermacher , 2nd, improved edition, Berlin 1817).

- Paul Vicaire (ed.): Plato: Lachès et Lysis . Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1963, pp. 63-106 (critical edition).

- Otto Apelt (translator): Plato's dialogues Charmides, Lysis, Menexenos . In: Otto Apelt (Ed.): Plato: All dialogues. Vol. 3, Meiner, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-7873-1156-4 (translation with introduction and explanations; reprint of the 2nd, revised edition, Leipzig 1922).

- Michael Bordt (translator): Plato: Lysis. Translation and commentary (= Ernst Heitsch, Carl Werner Müller (Hrsg.): Platon: Werke. Translation and commentary. Vol. V 4). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-525-30419-6 .

- Ludwig Georgii (translator): Lysis . In: Erich Loewenthal (ed.): Plato: Complete works in three volumes. Vol. 1, unchanged reprint of the 8th, revised edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-17918-8 , pp. 205-237.

- Rudolf Rufener (translator): Plato: Frühdialoge (= anniversary edition of all works. Vol. 1). Artemis, Zurich / Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7608-3640-2 , pp. 81–115 (with introduction by Olof Gigon pp. XLVII – LVI).

Humanistic translation (Latin)

- Stefano Martinelli Tempesta (Ed.): Platonis Euthyphron Francisco Philelfo interprete, Lysis Petro Candido Decembrio interprete . Società Internazionale per lo Studio del Medioevo Latino, Florence 2009, ISBN 978-88-8450-357-2 , pp. 105–171 (critical edition; cf. the editor's corrections in his essay Ancora sulla versione del “Liside” platonico di Pier Candido Decembrio, In: Acme 63/2, 2010, pp. 263-270).

- Elena Gallego Moya (ed.): La versión latina de Pier Candido Decembrio del Lysis de Platón . In: Boris Körkel u. a. (Ed.): Mentis amore ligati. Latin friendship poetry and poet friendship in the Middle Ages and modern times . Mattes, Heidelberg 2001, ISBN 3-930978-13-X , pp. 93-114 (critical edition).

literature

Overview representations

- Louis-André Dorion: Lysis . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques. Volume 5, Part 1, CNRS Éditions, Paris 2012, ISBN 978-2-271-07335-8 , pp. 741-750.

- Michael Erler : Platon (= Hellmut Flashar (Hrsg.): Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , volume 2/2). Schwabe, Basel 2007, ISBN 978-3-7965-2237-6 , pp. 156-162, 602f.

- Brigitte Theophila Schur: "From here to there". The concept of philosophy in Plato. V & R unipress, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8471-0161-1 , pp. 197-214.

Investigations

- David Bolotin: Plato's Dialogue on Friendship. An Interpretation of the Lysis, with a New Translation . Cornell University Press, Ithaca 1979, ISBN 0-8014-1227-7 .

- Hans-Georg Gadamer : Logos and Ergon in the Platonic Lysis . In: Hans-Georg Gadamer: Small writings. Volume 3: Idea and Language . Mohr, Tübingen 1972, ISBN 3-16-831831-0 , pp. 50-63.

- Terry Penner, Christopher Rowe: Plato's Lysis . 2nd, corrected edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-79130-4 .

- Horst Peters: Plato's Dialogue Lysis. An unsolvable riddle? Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-631-37754-1 .

- Florian Gernot Stickler: A new run through Plato's early Lysis dialogue. From semantic systems and affections to Socratic pedagogy . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-8260-4247-8 (dissertation with partly bold hypotheses).

- Thomas Alexander Szlezák : Plato and the written form of philosophy. Interpretations of the early and middle dialogues . De Gruyter, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-11-010272-2 , pp. 117-126.

Web links

- Lysis , Greek text from the edition by John Burnet , 1903

- Lysis , German translation after Friedrich Schleiermacher, edited

- David Robinson, Fritz-Gregor Herrmann: Commentary

Remarks

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 203b. Cf. Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Plato, Lysis 223b. See Louis-André Dorion: Lysis . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, pp. 741–750, here: 741.

- ↑ Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 316f.

- ↑ Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, p. 94f.

- ↑ See Francisco J. Gonzalez: How to Read a Platonic Prologue: Lysis 203a – 207d . In: Ann N. Michelini (ed.): Plato as Author , Leiden 2003, pp. 15–44, here: 36f.

- ↑ See Francisco J. Gonzalez: How to Read a Platonic Prologue: Lysis 203a – 207d . In: Ann N. Michelini (Ed.): Plato as Author , Leiden 2003, pp. 15–44, here: 25–27, 34f .; Catherine H. Zuckert: Plato's Philosophers , Chicago 2009, pp. 512-515.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 206d.

- ↑ Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, p. 317; see. Pp. 119f., 174, 195f., 202f. Luc Brisson estimates the age of Lysis and Menexenos at around sixteen: Lysis d'Axioné and Ménexène de Péanée . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 4, Paris 2005, pp. 217 and 466, on little more than eleven or twelve years Louis-André Dorion: Lysis . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, pp. 741–750, here: 741f. Cf. Catherine H. Zuckert: Plato's Philosophers , Chicago 2009, p. 483, note 2.

- ↑ See Andrea Capra: Poeti, eristi e innamorati: il Liside nel suo contesto . In: Franco Trabattoni u. a. (Ed.): Platone: Liside , Vol. 2, Milano 2004, pp. 173-231, here: 180-196.

- ↑ On the relationships between adolescents, which are characterized by both eroticism and rivalry and questions of ranking, see Catherine H. Zuckert: Plato's Philosophers , Chicago 2009, pp. 515–523.

- ↑ See on the find Ronald S. Stroud : The Gravestone of Socrates' Friend, Lysis . In: Hesperia 53, 1984, pp. 355-360.

- ↑ For historical lysis see Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 195–197 (with family tree); John K. Davies: Athenian Property Families, 600-300 BC , Oxford 1971, pp. 359-361.

- ↑ Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, pp. 68f .; Elizabeth S. Belfiore: Socrates' Daimonic Art , Cambridge 2012, pp. 103-108.

- ^ On historical Menexenos see John S. Traill: Persons of Ancient Athens , Volume 12, Toronto 2003, p. 227 (No. 644855; compilation of the evidence); Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 202f .; Stavros Tsitsiridis (Ed.): Platons Menexenos , Stuttgart 1998, p. 53f.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 211b-c.

- ↑ According to Lysis 206d, Menexenos was an anepsios of Ktesippos, which is often translated as "nephew"; but what is probably meant is “cousin”, see Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 120, 202; Luc Brisson: Ménexène de Péanée . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 4, Paris 2005, p. 466.

- ↑ See on Ktesippos Luc Brisson: Ctésippe de Péanée . In: Richard Goulet (Ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 2, Paris 1994, pp. 532f .; Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 119f .; Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and commentary , Göttingen 1998, p. 110.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 3.46; see. Richard Goulet: Hippothalès d'Athènes . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 3, Paris 2000, p. 801; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 157f .; Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, p. 174; Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, p. 110 and note 211.

- ↑ See on the behavior of the Hippothales Elizabeth S. Belfiore: Socrates' Daimonic Art , Cambridge 2012, pp. 98-103 and the literature cited there.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 203a-205d.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 205d-207b.

- ↑ For earlier history and contemporary use of the relevant terms, see Michael Bordt: Platon: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, pp. 50–60; on Plato's use of language and translation problems, see Bordt's remarks on pp. 154–157. See David B. Robinson, Plato's Lysis: The Structural Problem . In: Illinois Classical Studies 11, 1986, pp. 63–83, here: 65–74, 80f .; Ernst Heitsch: Plato and the beginnings of his dialectical philosophizing , Göttingen 2004, p. 111f .; Terry Penner, Christopher Rowe: Plato's Lysis , 2nd corrected edition, Cambridge 2007, p. 249.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 207b-210d.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 210c-211d.

- ↑ On this double meaning and Plato's handling of it see David Glidden: The Language of Love: Lysis 212a8-213c9 . In: Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 61, 1980, pp. 276-290.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 211d-212d.

- ↑ See Francisco J. Gonzalez: How to Read a Platonic Prologue: Lysis 203a – 207d . In: Ann N. Michelini (ed.): Plato as Author , Leiden 2003, pp. 15–44, here: 23f.

- ↑ See Naomi Reshotko: Plato's Lysis: A Socratic Treatise on Desire and Attraction . In: Apeiron 30, 1997, pp. 1-18.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 212d-213d.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 17.218.

- ↑ See the study by Carl Werner Müller : Same to Same. A principle of early Greek thought , Wiesbaden 1965, especially p. IX f., 177–187.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 213d-214e.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 214e-216a.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 216a-b.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 216c-218c.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 218c-219c.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 219c-220b. See the commentary by Terry Penner, Christopher Rowe: Plato's Lysis , 2nd, corrected edition, Cambridge 2007, pp. 125-133, 257-269.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 220b-221d.

- ↑ On the term "relative" in Plato and in general usage, see Francisco Gonzalez: Socrates on Loving One's Own: A Traditional Conception of φιλíα Radically Transformed . In: Classical Philology 95, 2000, pp. 379-398; Albert Joosse: On Belonging in Plato's Lysis . In: Ralph M. Rosen, Ineke Sluiter (ed.): Valuing Others in Classical Antiquity , Leiden 2010, pp. 279-302. See Peter M. Steiner: Psyche bei Platon , Göttingen 1992, pp. 30–32.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 221d-222b.

- ^ Plato, Lysis 222b-d.

- ↑ Plato, Lysis 222e-223b.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 160.

- ^ Louis-André Dorion: Lysis . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, pp. 741–750, here: 746.

- ↑ See the overview in William KC Guthrie: A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 4, Cambridge 1975, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Valentin Schoplick: The platonic dialogue Lysis , dissertation Freiburg 1968, pp. 55, 67; Maria Lualdi: Il problema della philia e il Liside Platonico , Milano 1974, pp. 110-121; Horst Peters: Plato's Dialogue Lysis. An unsolvable riddle? , Frankfurt am Main 2001, pp. 27f., 74f., 120-125; Donald Norman Levin: Some Observations Concerning Plato's Lysis . In: John P. Anton, George L. Kustas (eds.): Essays in Ancient Greek Philosophy , Albany 1972, pp. 236-258, here: 247f.

- ^ Gregory Vlastos: The Individual as an Object of Love in Plato . In: Gregory Vlastos: Platonic Studies , 2nd edition, Princeton 1981, pp. 3–42, here: 35–37. Cf. Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, pp. 202–204.

- ↑ See the overview in Michael Bordt: Platon: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, pp. 204–207. Compare with Jan Szaif: Striving Nature and Interpersonality in Plato's Concept of Philia (Lysis 213D – 222D) . In: Mechthild Dreyer , Kurt Fleischhauer (ed.): Nature and Person in the ethical dispute , Freiburg / Munich 1998, pp. 25–60, here: 43–52; Terry Penner, Christopher Rowe: Plato's Lysis , 2nd corrected edition, Cambridge 2007, pp. 139-153, 245-279; Ursula Wolf : The search for the good life. Platons Frühdialoge , Reinbek 1996, pp. 138, 142; Don Adams: A Socratic Theory of Friendship . In: International Philosophical Quarterly 35, 1995, pp. 269-282, here: 272f.

- ↑ Matthias Baltes: Epinoemata , Leipzig 2005, pp 171-177; see. P. 70f.

- ↑ Werner Jaeger: Paideia , Berlin 1989 (reprint of the 1973 edition in one volume), p. 761.

- ↑ Charles H. Kahn: Plato and the Socratic dialogue , Cambridge 1996, pp. 264-267, 281-291; Holger Thesleff : Platonic Patterns , Las Vegas 2009, p. 296f.

- ^ David K. Glidden: The Lysis on Loving One's Own . In: The Classical Quarterly 31, 1981, pp. 39-59, here: 55-58.

- ^ Gregory Vlastos: The Individual as an Object of Love in Plato . In: Gregory Vlastos: Platonic Studies , 2nd edition, Princeton 1981, pp. 3–42, here: 6–10.

- ↑ Michael D. Roth: Did Plato Nod? Some Conjectures on Egoism and Friendship in the Lysis . In: Archive for the History of Philosophy 77, 1995, pp. 1-20. See Mary P. Nichols: Socrates on Friendship and Community , Cambridge 2009, pp. 178-183.

- ^ Maria Lualdi: Il problema della philia e il Liside Platonico , Milano 1974, p. 21f. Victorino Tejera pleads for inauthenticity: On the Form and Authenticity of the Lysis . In: Ancient Philosophy 10, 1990, pp. 173-191; however, his reasoning has not met with approval in specialist circles.

- ↑ For classification as a youth work advocates u. a. Maria Lualdi: Il problema della philia e il Liside Platonico , Milano 1974, pp. 22-37. On the stylistic features, see Gerard R. Ledger: Re-counting Plato , Oxford 1989, pp. 218f.

- ↑ See also William KC Guthrie: A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 4, Cambridge 1975, pp. 134f .; Andrea Capra: La data di composizione del Liside . In: Franco Trabattoni u. a. (Ed.): Platone: Liside , Vol. 1, Milano 2003, pp. 122-132; Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, pp. 102-106; Valentin Schoplick: The Platonic Dialogue Lysis , Dissertation Freiburg 1968, pp. 73–83; Horst Peters: Plato's Dialogue Lysis. An unsolvable riddle? , Frankfurt am Main 2001, pp. 87-118; Franz von Kutschera : Plato's Philosophy , Vol. 1, Paderborn 2002, p. 166f.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Nathalie von Siemens: Aristotle about friendship , Freiburg / Munich 2007, p. 22; Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, p. 42 and note 3; Terry Penner, Christopher Rowe: Plato's Lysis , 2nd corrected edition, Cambridge 2007, pp. 312-322.

- ↑ See the work of Kolotes Michael Erler: The Epicurus School . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4/1, Basel 1994, p. 236f .; Tiziano Dorandi, François Queyrel: Colotès de Lampsaque . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 2, Paris 1994, pp. 448–450, here: 449.

- ↑ Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1998, pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Mauro Bonazzi: Tra scetticismo e dogmatismo: il "Liside" nell'antichità . In: Franco Trabattoni u. a. (Ed.): Platone: Liside , Vol. 2, Milano 2004, pp. 233–245.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 3: 57-59.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 3.35. See Alice Swift Riginos: Platonica , Leiden 1976, p. 55.

- ↑ Prolegomena to the Philosophy of Plato 3, ed. by Leendert Gerrit Westerink : Prolégomènes à la philosophie de Platon , Paris 1990, p. 6; see. P. 51.

- ↑ Holger Thesleff: Platonic Patterns , Las Vegas 2009, p. 296.

- ^ Corpus dei Papiri Filosofici Greci e Latini (CPF) , Part 1, Vol. 1 ***, Firenze 1999, pp. 135-139.

- ↑ Oxford, Bodleian Library , Clarke 39 (= "Codex B" of the Plato textual tradition). For the text transmission, see Franco Trabattoni u. a. (Ed.): Platone: Liside , Vol. 1, Milano 2003, pp. 13-106.

- ^ Maria-Jagoda Luzzatto: Codici tardoantici di Platone ed i cosidetti Scholia Arethae . In: Medioevo greco 10, 2010, pp. 77–110.

- ↑ James Hankins: Plato in the Italian Renaissance , 3rd edition, Leiden 1994, pp. 418-420; on the dating Stefano Martinelli Tempesta (ed.): Platonis Euthyphron Francisco Philelfo interprete, Lysis Petro Candido Decembrio interprete , Florence 2009, pp. 112–114.

- ↑ Marsilii Ficini Opera , Volume 2, Paris 2000 (reprint of the Basel 1576 edition), pp. 1272–1274. An English translation of the introduction is provided by Arthur Farndell: Gardens of Philosophy. Ficino on Plato , London 2006, pp. 30-34.

- ↑ See Laszlo Versenyi: Plato's Lysis . In: Phronesis 20, 1975, pp. 185-198, here: 185f .; Terry Penner, Christopher Rowe: Plato's Lysis , 2nd corrected edition, Cambridge 2007, pp. 297f .; Thomas Alexander Szlezák: Plato and the writing of philosophy , Berlin 1985, p. 117.

- ^ Friedrich Schleiermacher: Lysis. Introduction . In: Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher: About the philosophy of Plato , ed. by Peter M. Steiner, Hamburg 1996, pp. 92–98, here: 96.

- ^ Lecture recording in: Friedrich Nietzsche: Werke. Critical Complete Edition , Department 2, Vol. 4, Berlin 1995, pp. 110f.

- ^ Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff: Platon. His life and works , 5th edition, Berlin 1959 (1st edition Berlin 1919), p. 141.

- ^ William KC Guthrie: A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 4, Cambridge 1975, pp. 143f.

- ↑ Terry Penner, Christopher Rowe: Plato's Lysis , 2nd, corrected edition, Cambridge 2007, p. 155. See Mary P. Nichols: Socrates on Friendship and Community , Cambridge 2009, pp. 178-183; Franz von Kutschera: Plato's Philosophy , Vol. 1, Paderborn 2002, p. 156.

- ↑ Werner Jaeger: Paideia , Berlin 1989 (reprint of the 1973 edition in one volume; first published in 1944), pp. 760f.

- ↑ Thomas Alexander Szlezák: Plato and the writing of philosophy , Berlin 1985, p. 117.

- ↑ Olof Gigon: Introduction . In: Platon: Frühdialoge (= anniversary edition of all works , vol. 1), Zurich / Munich 1974, pp. IL – LI, LV f.

- ^ Francisco J. Gonzalez: Plato's Lysis: An Enactment of Philosophical Kinship . In: Ancient Philosophy 15, 1995, pp. 69–90, here: 89.

- ↑ Michael Bordt: Plato: Lysis. Translation and commentary , Göttingen 1998, p. 5.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 159.

- ↑ Terry Penner, Christopher Rowe: Plato's Lysis , 2nd, corrected edition, Cambridge 2007, pp. XII, 298f.

- ↑ Ernst Heitsch: Plato and the beginnings of his dialectical philosophizing , Göttingen 2004, p. 111.

- ^ Rudolf Borchardt: The conversation about forms. Platons Lysis deutsch , Stuttgart 1987 (first edition Leipzig 1905), pp. 63–97.