Midlothian campaign

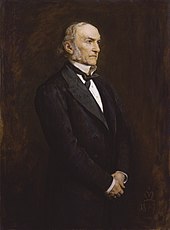

The Midlothian Campaign ( English Midlothian campaign ) was a series of election campaign appearances that the liberal politician William Ewart Gladstone in the years 1879 and 1880 in his new Scottish constituency Edinburghshire, commonly called Midlothian, completed. Organized at great expense by the liberal House of Lords Earl of Rosebery as a media event based on the US model, the Midlothian campaign is considered a milestone and the first modern election campaign in the political history of the United Kingdom . In contrast to the previously established model, Rosebery's election campaign organization addressed broad masses of the local population and tried to stage the appearances with the involvement of the press as a major media event in order to secure the campaign's nationwide attention. As in the USA, the performances were accompanied by a supporting program with parades, horse parades and fireworks.

Gladstone, who rode sharp attacks on the conservative government of his hated long-time rival Benjamin Disraeli during his appearances, repeatedly confirmed his reputation as a popular and close to the people politician ("The People's William") acquired in earlier decades through the Midlothian campaign and cemented it the following decade, his supremacy as a leader within the Liberal Party. In the early general election in 1880 he triumphed in Midlothian and, thanks to the nationwide success of the Liberal Party, subsequently formed his second government as prime minister.

Gladstone's personal situation in the mid-1870s

After six years in government, the Liberals under Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone suffered a definite defeat in the British general election in 1874 and had to hand over power to the Conservative Party under its leader Benjamin Disraeli . After a brief transition period, Gladstone also gave up the leadership of the Liberal Party because he did not want to act again as opposition leader. He retained his seat in Parliament, however, and intended to continue operating from the back benches should Church of England issues appear on the political agenda. After another personal defeats - he had of the House (as part of the House of Commons adopted) Public Worship Regulation Act 1874 (which should ban the growing Roman ritualism in the Anglican Church of England) an extremely painful for him vote defeat suffered - Gladstone, however, found increasingly unrelated to the prevailing mood in the country, which followed the agenda of Disraeli's re-emerging conservative party.

In 1875 he therefore kept the private promise he had made decades ago and withdrew from politics. Instead, he spent a lot of time at his Welsh country estate, Hawarden Castle , where he devoted himself to his Homer studies, especially religious studies and, among other things, wrote a treatise on heavenly punishment after death. After his self-chosen retreat, Lord Hartington in the House of Commons and Lord Granville in the House of Lords took over the leadership of the Liberals. Gladstone's biographers agree, however, that his exile was never complete and that he secretly flirted with a return to active politics as soon as a suitable occasion presented itself.

The Bulgarian uprising

While Gladstone was in exile, the April Bulgarian uprising against Ottoman rule began in the Balkans in April 1876 . This was brutally suppressed by the Ottoman army and supporting irregular troops ; Massacres of the Bulgarian civilian population were also committed. So the Oriental question came back on the political agenda. London has long maintained close ties with the Ottoman government, the Sublime Porte. The protection of the Ottoman Empire, now known as the " sick man on the Bosporus ", was considered essential for British trade, the interests of power politics and the protection of the British Empire from Russian expansion . Great Britain, for example, had already intervened with Napoleonic France in the Crimean War in the mid-1850s to secure the continued existence of the Ottoman Empire. Especially Constantinople and the Straits of the Bosporus and Dardanelles were the key to defending these interests in British eyes. Letting these strategically neuralgic points fall into Russian hands seemed almost unthinkable for political London from this point of view, since this would inevitably have led to a rapid increase in Russia's power and endangered the existing power structure . It is true that voices in the conservative party had become loud that now considered this dogma to be out of date, but the sea route to British India also seemed secured by purchasing the Suez Canal . However, the fall of several independent khanates in Central Asia in the 1860s, which came under Russian rule, again demonstrated in the eyes of Disraeli the importance of the Ottoman Empire as a shield against Russian expansion. With Disraeli's election victory, Britain’s foreign policy inactivity, which had existed since 1865 and was supported by both parties, ended. Disraeli himself paid special attention to foreign policy and also especially to the fate of British India. For him, the key to the security of British India and the sea route there via the Suez Canal still lay in Constantinople, which should not fall into Russian hands. He was also generally suspicious of the growing nationalism, which was the driving force behind the uprising against Ottoman rule.

Prelude to the Midlothian Campaign: Extra-Parliamentary Protest Movements

News of atrocities and victims perpetrated by the Bulgarian civilian population initially reached Europe and the British public very little, but immediately met with great interest. In June, the Liberal-affiliated Daily News reported on atrocities and thousands of deaths, causing a storm of indignation among large parts of the public. The British government and Prime Minister Disraeli initially ignored the incoming reports; Sir Henry Elliot , British Ambassador to Constantinople from 1867 and a staunch Turkophile, passed on the appeasement of the Ottoman government to London. The also Turkophile British consul in Sarajevo, Holmes, passed on the statements of the local officials without checking and stated that the uprising was more of a disturbance by foreign gangs caused by Serbian agitators. In a statement in the House of Commons, Disraeli then dismissed the reports as "little more than coffee shop chatter". He also firmly refused a possible military intervention by Tsarist Russia. Even under pressure from Queen Victoria , Disraeli openly threatened a general European war between the great powers in this case. At the same time he let Lord Salisbury negotiate discreetly with the Russian side on a compromise agreement. While Victoria was emphatically militant and wanted to act much more confrontationally than her prime minister throughout the crisis, Disraeli on the other hand was faced with a skeptical cabinet that wanted to act very cautiously.

Meanwhile, intellectuals and clergy began to organize protests. After initial hesitation - the Liberal leaders were more inclined to support the policies of the Conservative government - the deeply religious Gladstone decided to lead the protest movement and embarked on a downright moral crusade. He published a pamphlet, The Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East , of which 40,000 copies were sold in four days alone. In it he accused the Turks of being an inhumane race, whose bestial lust drives them to commit outrages. He made three key demands: an end to the anarchic malregulation in the Ottoman Empire, the prevention of further violence through administrative reforms and the restoration of the British name, which had been badly damaged by the inactivity of the government. The only possible reaction he called for joint intervention by a united Europe and to drive the Turks out of Europe.

Gladstone condemned the policies of his long-time adversary and adversary Disraeli, who had been ennobled as Earl of Beaconsfield in August 1876 and from that point in the House of Lords , more sharply than ever and invented the term "Beaconsfieldism". If the political rivalry between the two had been marked by great animosity and strong mutual dislike for many years, the relationship between them was now increasingly hateful in the judgment of their biographers. Gladstone spoke at a mass rally in Blackheath in the pouring rain to about 10,000 people and called for a “coalition of the willing” to overcome tyranny and bring about national self-determination for the Bulgarians. To this end, he defended the Russian government's right to military intervention in the Balkans. At a rally in London's St James's Hall, attended by Anthony Trollope , John Ruskin and the Duke of Westminster , and letters of support were read from Thomas Carlyle , Charles Darwin and Robert Browning , he condemned the Prime Minister's military "saber rattle". In ever more harsh form, he demanded intervention in his subsequent appearances. He also used stereotypical images against Jews and Jewish influence in Great Britain. Historian Geoffrey Alderman attributed these attacks in part to the break between the Liberal Party and the Jewish electorate. Some of the attacks on Prime Minister Disraeli in the liberal press, some of which, like the Church Times , only spoke of the “Jewish Prime Minister”, were enriched with anti-Semitic stereotypes by the authors . Disraeli, who remained silent for a long time about Gladstone's accusations and the sensational press, ended up calling Gladstone a warmonger in a speech. The liberal party leaders Hartington and Granville were embarrassed about his political campaign, since they saw the majority of the British population (again) united behind the position of Prime Minister, despite the initially great public outrage over the Turkish acts of violence. They also saw Gladstone's tactics as an incitement to the masses, which they considered dangerous. Its second published pamphlet, Lessons in Massacre , only sold 7,000 times. This change in mood in parts of the population was also reflected in two public demonstrations against him in London's Hyde Park. These were organized by conservative supporters.

Regardless of the British warnings declared Russia the Porte the war . In response to the Russian intervention, a British fleet was moved to the Dardanelles in January 1878. In Great Britain this immediately created a tense situation and further polarization in public opinion, which was more divided on an issue of British foreign policy than it has been since the French Revolution . Both the conservative cabinet and the liberal opposition were deeply divided; Cabinet member Lord Carnarvon resigned because he did not want to support a war on the side of Turkey. The subsequent hard peace of San Stefano of March 1878, which went beyond the secretly negotiated agreements, ultimately also led to the resignation of Foreign Minister Lord Derby , who was immediately replaced by Lord Salisbury. He was able to soften the Treaty of San Stefano through bilateral negotiations with Russian Foreign Minister Shuvalov . At the convened Berlin Congress , the diplomatic solution to the crisis was also brought about by treaty between the major European powers. Disraeli returned to Great Britain in triumph and spoke publicly of an "Peace with Honor".

Even if Prime Minister Disraeli had achieved a diplomatic triumph, his victory was generally short-lived. The country's economic situation had deteriorated since the mid-1870s; a series of hard winters and rainy summers led to crop failures and economic losses. The Great Deflation of the world economy hit the established industrial society of Great Britain particularly hard. Added to this were foreign policy defeats such as the Battle of Isandhlwana , which, although not the government's fault, were still blamed on the Prime Minister.

The Midlothian constituency

Gladstone interpreted the mood in the country as extremely favorable; at his country estate Hawarden Castle, he evaluated the election statistics (good for the Liberals) in by-elections. In a conversation with Lord Granville, he said that the Liberals had won ten by-elections since the dispute over the Oriental question and said: “The kettle is starting to boil; I hope he doesn't boil over too quickly. ”By now he was already planning his full return to active politics and was looking for a new constituency. Never satisfied with his previous constituency, Greenwich, he looked for an alternative and decided not to run again in Greenwich. At the same time as the announcement of his decision, he let it be known that he was open to offers from liberal local organizations from other constituencies. He was then contacted on the one hand by the Liberals from Leeds, an urban constituency with a strong liberal tradition and a safe stronghold for the Liberal Party.

On the other hand, the Earl of Rosebery offered him the Scottish constituency of Midlothian. Commonly known colloquially mostly as Midlothian, the constituency of Edinburghshire, created in 1708, was actually a marginal constituency in the late 19th century with only 3,620 eligible voters. However, the constituency, which encompassed the hinterland of the Scottish capital Edinburgh and was characterized by a metropolitan climate influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment , was disproportionately important due to other factors. Two of Scotland's most influential aristocratic families, the Duke of Buccleuch and the Earl of Rosebery , fought for electoral supremacy here since the 1860s, making Midlothian a highly competitive constituency in the general election. In the general election of 1868, the Liberals broke decades of conservative supremacy; In 1874, Lord Dalkeith , heir to the Duke of Buccleuch, won the constituency back to the Conservative Party with a slim majority. Rosebery, who had invited Gladstone to run, assured him that the Midlothian constituency was open to his liberal ideas and ideals. Scotland increasingly represented a stronghold of liberalism anyway.

Rosebery's campaign organization

At the same time, Rosebery, who was one of the richest men in Scotland with widespread, extensive land holdings and was recently married to Hannah de Rothschild of the Rothschild dynasty , promised that he would be the organizer of all campaign costs. This was an important assurance because campaigning in a hard-fought constituency could cost a candidate around £ 3,000 (which would be around £ 150,000 by today's standards) and MPs were not paid. According to his own later estimate, Rosebery even invested a sum of approximately 50,000 pounds (in today's value more than 2.5 million pounds) in the election campaign, but his biographer Robert Rhodes James later doubted the full amount of this sum. Gladstone then decided to leave the safe, liberal constituency of Leeds open to his son Herbert, who was also politically active , and to run for office in Midlothian himself.

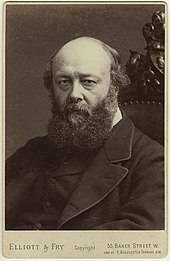

Rosebery became Gladstone's campaign manager. Rosebery had been on friendly terms with Disraeli for years, who saw him as a soul mate and would have liked to see him as a conservative. However, due to his family's strong Whig tradition, Rosebery remained a liberal. He had sat in the House of Lords since May 1868; however, he was only moderately active there and described it as a "gilded cage", partly because the Liberals were permanently in the minority there. Basically of a strongly paternalistic attitude, he also harbored sympathy for the British working class and had in the past launched a public campaign against the exploitation of children in the brickworks of Glasgow. Rosebery was fascinated by American election campaigns; after attending the Democratic Party's National Convention in New York in 1873 , he spoke of a great political lesson. As an election campaign manager, he began at great financial expense to incorporate his experience from the USA, to transfer some American methods and to bring them into Gladstone's election campaign.

Rosebery's innovations were almost revolutionary for the previous election campaigns of the Victorian Age : Up to now, the candidates rarely spoke in front of a large audience and often visited the large country houses in order to secure the support of important magnates on site. In addition, they mainly focused on their presence in the House of Commons, as the House of Commons debates were extensively printed in the newspapers. In contrast, the election campaign now became a mass event in which the candidate addressed the entire population of his own constituency. This ensured that attention was maximized, as the printed House of Commons debates did not appeal to many sections of the readership, whereas the direct form of communication between candidate and electorate through campaign speeches (which were also printed the next day) attracted much more attention. In the run-up to the event, large rooms were rented for the performances; As has already been tried in the USA, the events were often accompanied by large parades, torchlight parades, equestrian parades and a final fireworks display. In addition, music bands were hired, triumphal arches installed and advertising banners hung up. To this end, the campaign was created as a media event right from the start and great care was taken to create optimal conditions for the press present for their reporting. Even if the highly media-conscious Gladstone seemed ostensibly aimed at the Scottish electorate in the constituency, the campaign was actually aimed at the nation. In addition, Rosebery, knowing the local conditions, gave Gladstone specific suggestions as to which particular topics he should focus on in his various appearances.

Rosebery's innovations were tailored to the significant expansion of the right to vote in 1867, which Disraeli's conservatives, in association with internal party liberal opponents of Gladstone, had passed in the great Reform Act of 1867 and the number of eligible voters suddenly rose from around 1.4 million 2.5 million had increased. It became apparent that a larger proportion of the working-class voters tended towards the Liberal Party. Gladstone's personal reputation, coupled with the more radical left-wing liberalism that advocated social reform, made the working class in its majority vote the liberals.

Gladstone's election campaign

Rosebery's family seat, Dalmeny House , became Gladstone's base for the duration of the election campaign. Although the next general election was still a long way off, Gladstone wanted to position himself early. On November 24th, when the election campaign started, he traveled by train from Liverpool. At every stopover, in Carlisle, Hawick and Galashiels, he gave short speeches to the population of the stopovers from the train - Rosebery had ordered a new type of Pullman saloon car with a platform at the end of the car for this purpose.

He made a total of 30 speeches in and around the Midlothian constituency over a two-week period. In the first week he made nine speeches focusing on Midlothian. The campaign was immediately well received, and when he appeared he was usually able to speak to several thousand people. Enthusiastic about the momentum of his own election campaign, he carefully noted in his diary the number of viewers at each of his appearances. The audience was not limited to local listeners, some interested people also traveled from the rest of Scotland. The audience also went far beyond those actually entitled to vote; Women also attended the election campaign events in large numbers. The British press covered the election campaign in great detail and, as was not unusual for the time, included Gladstone's speeches in their articles the next morning. As a result, the campaign achieved national significance far beyond the borders of the constituency. However, not all press reviews were consistently friendly; the leading medium, the London Times , in its November 29 editorial, questioned whether the country really wanted public affairs to be discussed with a rhetoric that would appeal much more to a mob.

Many of Gladstone's speeches lasted up to five hours. In terms of content, it drew a broad framework and covered the entire field of politics. He usually gave brief presentations to his audience on basic principles of the Liberal Party mixed with his strong (Anglican) religious beliefs. He then devoted himself extensively to foreign and domestic politics. A strong element of the speeches was also the condemnation of "Beaconsfieldism", which he branded as immoral.

In relation to the foreign policy of the conservatives, he criticized the government's adventurism and deplored the victims of Prime Minister Disraeli's colonial wars in sentimentally drawn pictures. He described the second Anglo-Afghan war as the most cocky invasion; The sanctity of life in the snow-covered villages of Afghanistan is just as inviolable as that of its British listeners. He also lamented the war against the Zulus , who were only defending their own country. To do this, he attacked the annexation of the Transvaal . He also accused Disraeli of betraying the ideals of Palmerston and Canning . He put forward three guiding principles on which British foreign policy should be based. In addition to the material prosperity of the British Empire and the cooperation in the European concert of the great powers , he drew the ideal image of a world community based on universal values, which should protect the weak.

Domestically, he primarily criticized the conservatives' financial conduct. In his November 29 speech, for example, he attacked the government's wasteful behavior: in six years of the Conservative government, he had seldom heard the Chancellor of the Exchequer , Sir Stafford Northcote , speak a resolute word on economic issues. The solid and sensible monetary economy of the past, first under Peel and then himself, was completely abandoned under the conservative government. In the second week Gladstone left Midlothian and the surrounding area and also traveled to various other Scottish cities. After a break over the Christmas days, he started campaigning again in the new year. Although formally just a simple backbencher, he overshadowed the official leaders of his party with the Midlothian campaign and thus underpinned his ambitions for the office of prime minister. In the event of a liberal election victory, his unspoken claim to the leadership of the party and the office of prime minister became increasingly likely.

The Liberal election victory in 1880

Disraeli was very calm and avoided any public reaction. Although he and the cabinet had not planned to dissolve parliament and hold an election to the lower house until 1881, two surprising conservative victories in by-elections resulted in a change of sentiment in the cabinet. In March 1880 the parliament was dissolved at short notice and new elections were scheduled.

However, the Conservatives were at a disadvantage from the start. With Prime Minister Disraeli, Foreign Minister Lord Salisbury and Lord Cranbrook , their three strongest speakers were now all in the House of Lords and were therefore excluded from active election campaigns. Sir Stafford Northcote, the leader of the conservative majority faction in the lower house since Disraeli's ennoblement , was seen as an extremely weak speaker who was unable to develop a positive effect on the conservative campaign. Disraeli had installed him as his successor as Conservative Leader in the House of Commons at a time when he still assumed that Gladstone's retirement would be permanent. He was quick to regret this decision when it took firm leadership from the Conservative faction in the House of Commons and a combative style of debate to withstand Gladstone's sharp attacks. However, Northcote could not deliver both, as he was considered timid and defensive. The economic crisis in agriculture in Great Britain hit the Conservative party particularly hard, as the land-owning nobility formed its traditional base. Lower lease income in recent years has led to reduced grants for the Tories' election campaign funds. The Conservative campaign focused on warning voters against the Liberals as they would introduce Home Rule (self-government) in British Ireland. This topic was supposed to be on the political agenda in the next few years, but at the time of the general election of 1880 it was still a new topic that took some getting used to and therefore not decisive for the election. In addition, the liberal election machine was already well established, while its conservative counterpart was surprised by the decision taken at short notice to hold a new election early. Gladstone took up his campaign with renewed energy. In terms of content, he repeated his speeches from the previous year; in a speech in Midlothian, he also described the election campaign as a "struggle between the classes and the masses".

The general election from March 31 to April 27, 1880 resulted in a large liberal majority. Nationwide, the swing was over 100 seats. Gladstone himself won the constituency by a majority of 211 votes (1579 to 1368 votes) against Lord Dalkeith. Nationwide, the general election was seen as a triumph for Gladstone. Queen Viktoria, who was in Baden-Baden in southern Germany, was shocked by the outcome of the election. For a long time she had been strongly in favor of Disraeli and had stated in 1879 that she could never accept Gladstone as minister again, since after his “brutal, malicious and dangerous behavior in the past three years she could never have a hint of trust in him For this reason she first invited Lord Hartington, the leader of the Liberals, to form a new government. Hartington gave her to understand, however, that no liberal government could be formed without Gladstone, but Gladstone categorically refuses to participate unless he is the Prime Minister himself. Although not formally the opposition leader, Queen Victoria then invited Gladstone (against her own will) to form a new government as Prime Minister. This subsequently formed his second cabinet .

He offered Rosebery a post as Undersecretary in the India Office; disappointed that he did not receive a cabinet post, the latter turned down the offer. However, through the Midlothian campaign, he had also achieved nationwide notoriety and became the leading figure of liberalism in Scotland in the eyes of political observers. In the following years he also developed into the most important representative of Scottish interests in Westminster's political establishment; it is largely due to his dedication that Gladstone created the post of Minister for Scotland in his third term .

Historical relevance of the Midlothian election campaign

The Midlothian campaign is believed to be the first modern election campaign in British political history. At the same time, the campaign also confirmed Gladstone's primacy as the most important liberal politician of his time and his reputation as an extremely popular and close to the people politician, which had earned him the nickname "The People's William" (German for example: The William of the People ). Thanks to his success, Gladstone was able to re-establish himself as the dominant figure of the Liberal Party for the next decade and outperform the Liberal party leaders in the battle for the office of Prime Minister.

In 1919, in his lecture “Politics as a Profession”, Max Weber judged Gladstone's campaign that a Caesarist-plebiscitarian element had entered politics: the dictator of the election battlefield had come on the scene. Paul Brighton partially contradicted Max Weber in 2016; the latter misjudged the actually decisive point, since the charisma and the personal contact during the appearance were to be rated as subordinate in comparison to the subsequent mass-compatible press coverage. It was only through the mass media of the 20th century such as radio and cinema that the effect Weber described was actually achieved in this form.

In the words of DC Somervell (1925), however, Gladstone returned to the political arena no more than old Gladstone, the mere successor of Peel ; rather, he has returned as "the pioneer of pre-war Lloyd George , the well-known Grand Old Man of the eighties, the greatest of all British demagogues."

In Robert Blake's ruling , Gladstone's campaigns injected a bitterness into the British political landscape unmatched since the Corn Laws dispute . He saw in the Midlothian campaign a fundamental conflict, which was represented by the two antipodes Gladstone and Disraeli, namely a higher moral right, put forward by Gladstone, and the permanent national interests, represented by Disraeli.

Patrick Jackson saw in his 1994 biography of Lord Hartington in the Midlothian campaign a hybrid amalgam of old and new campaign methods; many speeches are very prosaic for modern readers, yet it is difficult to escape the effect of some passages. HC G Matthew judged that the Midlothian campaign had little to do with the Parliament seat itself. Rather, it was a matter of establishing gladstoniasm as the dominant current in liberal politics and of winning over the new electorate that had only recently been eligible for elections. The real target group was the newspaper reading public in the country.

Roy Jenkins said in his 1995 biography about Gladstone that his rhetoric in 1876 was stronger than his actual knowledge of the situation in Bulgaria. However, he saw the liberal election victory in 1880 as a success created by Gladstone.

In his biography on Disraeli from 2000, Edgar Feuchtwanger appeared in retrospect to see Gladstone's Midlothian campaign as a significant step in modern political persuasion. His strategy of addressing people on both a moral and a factual level was a powerful strategy.

In 2009, John Campbell saw Gladstone's Midlothian campaign with his moral passion as the source of inspiration for the peace movement in the 1920s, the Easter marches of the nuclear disarmament movement in the 1950s and the opponents of the 2003 Iraq war . At the same time, not only the opponents of the 2003 Iraq war, but also Tony Blair was inspired by Gladstone's campaign in his moral-based foreign policy interventionism . In 2019 Dominik Geppert argued in this regard that Tony Blair's foreign policy was in the direct tradition of a certain British foreign policy, which could be described as "Gladstonian foreign policy". The moralization of foreign policy, as it was openly pursued by Blair, can be traced back directly to the common religious drive of the two prime ministers; in this respect, Blair openly referred to Gladstone's Midlothian campaign in the 1999 Kosovo crisis .

literature

- Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007 ISBN 978-1-84413-312-3 . Pp. 257-305.

-

Robert Blake : Disraeli. Prion, London 1998, ISBN 1-85375-275-4 (EA London 1967)

- German: Disraeli. A biography from the Victorian era. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-7973-0360-2 (translated by Klaus Dockhorn).

- Dominik Geppert: Tony Blair, the Iraq war and the legacy of Wiliam Ewart Gladstone. In: Peter Geiss, Dominik Geppert, Julia Reuschenbach (eds.): A value system for the world? Universalism in the past and present. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2019, ISBN 978-3-8487-5378-9 . Pp. 309-331.

- WE Gladstone: Midlothian Speeches 1879. Leicester University Press, Leicester 1971, ISBN 0-7185-5009-9 .

- Patrick Jackson: The Last of the Whigs: A Political Biography of Lord Hartington, Later Eight Duke of Devonshire. Associated University Presses, London 1994, ISBN 0-8386-3514-8 . Pp. 97-114.

- Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, ISBN 0-333-60216-1 . ( Whitbread Prize for Biography 1995) pp. 399-434.

- Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, ISBN 978-1-84885-925-8 . Pp. 157-183.

- HC G Matthew: Gladstone: 1809-1898. Clarendon Press, London 1997, ISBN 0-19-820696-8 . Pp. 293-313.

- RW Seton-Watson : Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern Question: A Study in Diplomacy and Party Politics. WW Norton & Company, London 1935, ISBN 978-0-393-00594-3 .

- Richard Shannon: Gladstone Volume II. 1865–1898. Penguin, London 1999, ISBN 0-8078-2486-0 . Pp. 230-248.

Web links

- Triumphant advance of the voting machine - Marco Althaus: Triumphant advance of the voting machine , politics & communication, February 2012

- Extract from the 3rd Midlothian speech (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 537 f.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 160.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, pp. 257 f.

- ^ HC G Matthew: Gladstone: 1809-1898. London 1997, pp. 257 f.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 125 f.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 261.

-

↑ DC Somervell: Disraeli and Gladstone. Jarrolds Publishers, London 1925, pp. 173 f.

Francis Birrell : Gladstone. Duckworth, London 1933, p. 89.

HC G Matthew: Gladstone: 1809-1898. London 1997, p. 256.

Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, pp. 260 f.

John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 126. - ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 126 f.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 269.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 576 f.

- ^ RW Seton-Watson: Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern Question: A Study in Diplomacy and Party Politics. WW Norton & Company, 1972, p. 3 ff.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 577.

- ^ RW Seton-Watson: Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern Question: A Study in Diplomacy and Party Politics. WW Norton & Company, 1972, p. 51.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 578 f.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 592.

- ^ RW Seton-Watson: Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern Question: A Study in Diplomacy and Party Politics. WW Norton & Company, 1972, p. 29 f.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 270.

-

^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 605.

Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 160. - ^ Ian St John: Disraeli and the Art of Victorian Politics. Anthem Press, London 2010, p. 158.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 126.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, p. 403.

-

^ RW Seton-Watson: Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern Question: A Study in Diplomacy and Party Politics. WW Norton & Company, 1972, pp. 75 f.

John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 126 f. - ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 267 f.

-

^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 606 f.

John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 133. - ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 272 ff.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 277.

- ^ Geoffrey Alderman: Modern British Jewry. Clarendon, Oxford 1992, p. 100.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 605.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 604.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 129.

- ↑ Edgar Feuchtwanger: Disraeli. A political biography. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2000, p. 195 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 618.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, pp. 415 f.

- ^ RW Seton-Watson: Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern Question: A Study in Diplomacy and Party Politics. WW Norton & Company, 1972, pp. 174 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 621 f.

- ^ Douglas Hurd , Choose your Weapons: The British Foreign Secretary . Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 2010, p. 149.

- ^ Douglas Hurd, Choose your Weapons: The British Foreign Secretary . Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 2010, p. 152 ff.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 284 ff.

-

^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 286.

RW Seton-Watson: Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern Question: A Study in Diplomacy and Party Politics. WW Norton & Company, 1972, p. 490. - ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 697 f.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 174 f.

- ^ Richard Shannon: Gladstone. God and Politics. Continuum, London 2007, p. 305.

- ^ Ian St John: Gladstone and the Logic of Victorian Politics. Anthem Press, London, 2010, p. 245.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 291.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 699.

- ↑ Patrick Jackson: The Last of the Whigs: A Political Biography of Lord Hartington, Later Eight Duke of Devonshire. Associated University Presses, London 1994, p. 98.

- ^ Michael Münter: Constitutional reform in the unitary state. The policy of decentralization in Great Britain. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Erlangen 2005, p. 85.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 175.

- ↑ Patrick Jackson: The Last of the Whigs: A Political Biography of Lord Hartington, Later Eight Duke of Devonshire. Associated University Presses, London 1994, p. 97.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: Nineteenth-Century Prime Ministers. Pitt to Rosebery. Palgrave Macmillan, London 2008, p. 328.

-

↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 134.

Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, p. 416. - ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 292.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: Nineteenth-Century Prime Ministers. Pitt to Rosebery. Palgrave Macmillan, London 2008, p. 327.

- ^ Paul Brighton: Original Spin: Downing Street and the Press in Victorian Britain. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2015, p. 205.

- ^ Paul Brighton: Original Spin: Downing Street and the Press in Victorian Britain. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2015, p. 203.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 295.

- ^ Paul Brighton: Original Spin: Downing Street and the Press in Victorian Britain. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2015, p. 204.

- ↑ Richard Shannon: Gladstone Volume II. 1865–1898. Penguin, London 1999, p. 235 f.

- ↑ Gottfried Niedhart: History of England in the 19th and 20th centuries. CH Beck, Munich 1996, p. 95 ff.

- ↑ Gottfried Niedhart: History of England in the 19th and 20th centuries. CH Beck, Munich 1996, p. 100.

- ^ Martin Roberts: Britain, 1846-1964: The Challenge of Change. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001, p. 67.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, p. 424.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 297 f.

- ^ HC G Matthew: Gladstone: 1809-1898. London 1997, p. 310.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, p. 425.

- ^ HC G Matthew: Gladstone: 1809-1898. London 1997, p. 311.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 176.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 700.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, p. 425 f.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 135.

- ↑ Richard Shannon: Gladstone Volume II. 1865–1898. Penguin, London 1999, p. 238 f.

- ↑ Edgar Feuchtwanger: Disraeli. A political biography. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2000, p. 195.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, p. 426.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 176 f.

-

^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 300.

Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 703. - ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 301.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 177.

-

↑ Edgar Feuchtwanger: Disraeli. A political biography. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2000, p. 189.

Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 566. - ↑ Edgar Feuchtwanger: Disraeli. A political biography. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2000, p. 189 ff.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 704.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 704.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, p. 431 ff.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 708.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 712.

- ↑ Patrick Jackson: The Last of the Whigs: A Political Biography of Lord Hartington, Later Eight Duke of Devonshire. Associated University Presses, London 1994, p. 110.

-

^ Francis Birrell: Gladstone. Duckworth, London 1933, p. 100.

FWS Craig: British Parliamentary Election Results 1832-1885. Macmillan Press, London 1977 (accessed online). - ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 304.

- ↑ Patrick Jackson: The Last of the Whigs: A Political Biography of Lord Hartington, Later Eight Duke of Devonshire. Associated University Presses, London 1994, p. 111.

- ↑ Richard Shannon: Gladstone Volume II. 1865–1898. Penguin, London 1999, p. 245.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, p. 308 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 717.

- ↑ Dick Leonard: The Great Rivalry: Gladstone and Disraeli. IB Tauris, London 2013, p. 179.

- ^ Michael Münter: Constitutional reform in the unitary state. The policy of decentralization in Great Britain. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Erlangen 2005, p. 84 ff.

- ^ Richard Price: British Society 1680-1880: Dynamism, Containment and Change. Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 289.

- ^ Richard Aldous: The Lion and the Unicorn. Gladstone vs. Disraeli. Pimlico, London 2007, pp. 142 f.

- ↑ Triumphant advance of the voting machine. 2012, accessed November 24, 2019 .

- ^ Paul Brighton: Original Spin: Downing Street and the Press in Victorian Britain. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2015, p. 204 f.

- ↑ DC Somervell: Disraeli and Gladstone. Jarrolds Publishers, London 1925, p. 189.

- ^ Robert Blake: Disraeli. Faber and Faber, London 2010, p. 603.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Conservative Party from Peel to Major. Faber and Faber, London 1997, p. 119 f.

- ↑ Patrick Jackson: The Last of the Whigs: A Political Biography of Lord Hartington, Later Eight Duke of Devonshire. Associated University Presses, London 1994, p. 100 f.

- ^ HC G Matthew: Gladstone: 1809-1898. Clarendon Press, London 1997, p. 299 f.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, pp. 403 f.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Gladstone: A Biography. Macmillan, London 1995, p. 436.

- ↑ Edgar Feuchtwanger: Disraeli. A political biography. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2000, p. 195 f.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 140.

- ↑ Tony Blair: My Way. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Munich 2010. p. 239.

- ↑ Dominik Geppert: Tony Blair, the Iraq war and the legacy of William Ewart Gladstone. In: Peter Geiss, Dominik Geppert, Julia Reuschenbach (eds.): A value system for the world? Universalism in the past and present. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2019. p. 311.

- ↑ Dominik Geppert: Tony Blair, the Iraq war and the legacy of William Ewart Gladstone. In: Peter Geiss, Dominik Geppert, Julia Reuschenbach (eds.): A value system for the world? Universalism in the past and present. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2019. P. 322 f.