Milon

Milon (also Milon von Kroton , Greek Μίλων Mílōn , Latin Milo ; * around 555 BC; † after 510 BC) was a Greek wrestler and one of the most famous athletes of the ancient world. He was the only one to win six times in all Panhellenic Games . He lived in his hometown of Croton (now Crotone in Calabria , southern Italy) and was a contemporary and follower of the philosopher Pythagoras of Samos . He was also a successful military leader.

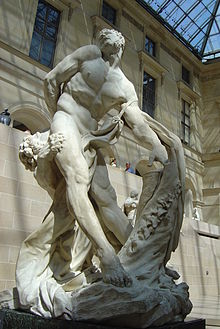

In modern art, Milon was received primarily through a legend about his death. Allegedly, as a test of strength, he wanted to tear apart a tree trunk that had been split in the forest and spread apart with wedges. After he had removed the wedges, he was trapped, could no longer free himself and was then eaten by wolves - in newer variants changed to a lion.

Life

Only the name of his otherwise unknown father Diotimos is known about Milon's origin. He achieved his first Olympic victory in his discipline, wrestling, among boys at the 60th Olympic Games in 540 BC. Chr .; therefore his birth is around 555 BC. To apply. His first Olympic victory among men was at the 62nd Games (532 BC); in the period 532-516 BC He won five times in a row. So he was a six-time winner. At the Pythian Games in Delphi , which, like the Olympic Games, were held every four years, he won seven times (the first time as a boy). He was ten times victorious in the Isthmian Games , which were held every two years, and nine times in the Nemean Games, which also take place every two years . This gave him the title of Periodonics six times , which was awarded to an athlete if he had won all four Panhellenic Games in a four-year cycle. Milon was the first periodonike whose name has been recorded and the only six-fold in all of antiquity. He was only missing an Olympic victory for the sevenfold period, but when he in 512 BC he was missing. For the seventh time BC competed in Olympia, he did not succeed in catching and throwing the younger opponent Timasitheos of Croton , who skillfully evaded him. The fight seems to have ended in a draw.

In 510 BC A war broke out between Kroton and Sybaris after the Crotoniats had refused to hand over refugees from Sybaris. Pythagoras, whose followers - the Pythagoreans - included Milon, lived in Croton at that time and advocated a tough attitude towards Sybaris. The crotoniats transferred the office of general to Milon, from which it can be seen that he played a prominent political role. He won a decisive victory, Sybaris was captured and sacked. This is the last recorded news from Milon's life; when he died is unknown.

Long after Milon's death, his house was the meeting place of the Pythagoreans of Croton. The house was burned down during the anti-Pythagorean riots that broke out around the middle or second half of the 5th century.

Milon is said to have been married to a daughter of Pythagoras named Myia . He had a daughter who married the famous doctor Demokedes , who was the personal physician of the Persian king Darius I and who then settled in Croton.

Legend and reality

The statements of the ancient sources about Milon's personality differ widely, and accordingly the Milon image in the modern age is also contradictory and partly shaped by clichéd ideas. Credible reports indicate that he had philosophical interests and belonged to the leading circles in his hometown; from this it can be concluded that he was of noble origin. A contrary, legendary tradition makes him appear as a stupid muscle man and glutton, who finally fell victim to his folly and excess; this fits the idea that he was an upstart. In part of the numerous anecdotes of the Milon legend and in later sources, he becomes the model of a negatively rated heavy athlete, whose one-sided development and emphasis on physical abilities makes him an astonishing, but basically ridiculous figure.

A report according to which Milon took the legendary hero Heracles as a model and accordingly went into battle with a lion's skin and club, probably reflects his actual self-image. It was only in a later, distorting representation that the cliché of a purely body-oriented man of strength without spiritual gifts emerged. The anecdotes about Milon originated from amazement at his unique successes and were later exaggerated, imaginatively embellished and turned into negative. The background to this was a generally negative assessment of competitive sport among philosophers and doctors. In addition to the legend of his death, the following stories were told:

- He used to carry a calf on his shoulders on a regular basis and, thanks to this training, could still lift it when it had grown into a bull.

- He lifted a four-year-old bull on his shoulders and carried it through the Olympic Stadium. He then slaughtered and ate it in a single day.

- No one could wrest a pomegranate in his hand from him, and the fruit remained undamaged.

- If he stood on an oiled disc , no one could push him off.

- He burst a gut string tied around his head by holding his breath and causing his forehead veins to swell.

- When one of the pillars of the house broke during a meal together, he supported the falling beams until everyone present had escaped.

- He ate 17 pounds of meat, 17 pounds of bread and drank around 10 liters of wine every day.

- He carried his own statue of victory to the Altis, the sacred grove of Olympia.

The following arguments speak against the assumption of low origins, a lack of education and low intelligence:

- According to a legend told by Herodotus , Demokedes boasted to the Persian king of his marriage to Milon's daughter. That would have been pointless if Milon had come from a lowly background, because sporting success would not have compensated for such a flaw and the announcement would not have impressed the king. Even if this news is historically incorrect, it shows that the marriage to Milon's daughter meant a social advancement for the famous doctor.

- The Pythagoreans, to which Milon belonged, were close to the leading Croton families; they had a religious and philosophical education and would hardly have accepted an uneducated person without appropriate inclinations and skills.

- The fact that the crotoniats entrusted command to Milon in a war that was vital for survival shows that his fellow citizens valued his intellectual abilities highly.

- Insofar as the sources allow conclusions to be drawn about the social origins of the athletes in the 6th century, it has been shown that participation in the Olympic Games was restricted to the aristocracy.

Modern reception

In 1682, the French sculptor Pierre Puget created a depiction of the legend of Milon's death in the forest ("Milon fighting the lion", now in the Louvre ). In the 18th century a Milon statue by Jean Joseph Vinache or Johann Gottfried Knöffler was created in the Great Garden in Dresden and one by Etienne-Maurice Falconet (now in the Louvre). In 1777 Johann Heinrich Dannecker made a dying Milon out of plaster, in 1784 Alexander Trippel designed the same theme. Goethe criticized such sculptural efforts violently because he found the subject repulsive.

literature

Overview representations

- Bruno Centrone: Milon de Crotone. In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques. Volume 4, CNRS Éditions, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-271-06386-8 , p. 522 f.

- Wolfgang Decker : Milon [2]. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , column 191 f.

- Oscar W. Reinmuth : Milon. 2. In: The Little Pauly . Volume 3. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-423-05963-X , Sp. 1303 f.

examination

- Valérie Visa-Ondarçuhu: Milon de Crotone, personnage exemplaire . In: Alain Billault (ed.): Héros et voyageurs grecs dans l'Occident romain . Éditions de Boccard, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-904-974-14-8 , pp. 33-62.

Remarks

- ↑ Another tradition gives six victories, but there were probably seven; see Joachim Ebert : Greek Epigrams for Sieger an Gymnischen und Hippische Agonen , Berlin 1972, p. 182.

- ↑ Joachim Ebert: Greek Epigrams on Sieger an Gymnischen and Hippischen Agonen , Berlin 1972, S. 182 f .; Wolfgang Decker : Sports in the Greek Antiquity , Munich 1995, p. 132.

- ↑ Kurt von Fritz : Pythagorean Politics in Southern Italy , New York 1940, p. 88. Domenico Musti judges differently: Le rivolte antipitagoriche e la concezione pitagorica del tempo , in: Quaderni Urbinati di cultura classica , Nuova Serie, vol. 36 no. 3, 1990, pp. 35–65, here: 43 ff., 60. Musti thinks that the mention of Milon's house suggests a violent confrontation while he was still alive.

- ↑ Augusta Hönle: Olympia in the politics of the Greek world , Bebenhausen 1972, pp. 82–84; Valérie Visa-Ondarçuhu: Milon de Crotone, personnage exemplaire . In: Alain Billault (ed.): Héros et voyageurs grecs dans l'Occident romain , Paris 1997, pp. 33–62, here: 50–52, 56–62.

- ↑ Christian Mann : Athlete and Polis in Archaic and Early Classical Greece , Göttingen 2001, p. 176 f .; Michael Poliakoff: Kampfsport in der Antike , Zurich 1989, pp. 128 ff., 243.

- ↑ The documents have been compiled and translated into French by Valérie Visa-Ondarçuhu: Milon de Crotone, personnage exemplaire . In: Alain Billault (ed.): Héros et voyageurs grecs dans l'Occident romain , Paris 1997, pp. 33–62, here: 45–62.

- ↑ Quintilian , Institutio oratoria 1,9,5.

- ↑ Christian Mann: Athlete and Polis in Archaic and Early Classical Greece , Göttingen 2001, p. 175; Domenico Musti: Le rivolte antipitagoriche e la concezione pitagorica del tempo , in: Quaderni Urbinati di cultura classica , Nuova Serie, Vol. 36 No. 3, 1990, pp. 35-65, here: 44.

- ↑ Joachim Ebert: Greek Epigrams on Sieger an Gymnischen und Hippischen Agonen , Berlin 1972, p. 183.

- ↑ Christian Mann: Athlete and Polis in Archaic and Early Classical Greece , Göttingen 2001, p. 36 f., 175.

- ↑ Martin Dönike: Pathos, Expression and Movement , Berlin 2005, p. 114.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Milon |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Greek wrestler and military leader |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 555 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 510 BC Chr. |