Munduruku

The Munduruku (Mundurukú, Mundurucú) are an indigenous people who live today in the state of Pará in the Brazilian Amazon region on the upper Rio Tapajós .

The Munduruku are best known for their extensive military campaigns, their tattoos and headhunting , which took place in the last third of the 18th century and well into the 19th century . In 1794 they were defeated by the Portuguese and then helped them wage war against other indigenous groups. Towards the end of the 18th century and in the 19th century, the Munduruku traded heavily, especially with feather headdresses, which brought many objects into the art collections of European rulers through European explorers.

On March 22nd, 2004 Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva handed over exactly 2,381,000 hectares of land to the 7,000 Indians of the Munduruku in the Amazon region. That corresponds roughly to the area of Tuscany.

Discovery and History

The Munduruku were first mentioned in 1768 by Monteiro Noronha as "Maturucu", who lived on the Rio Maués at that time . In 1769 the warlike Mundurucú moved to Tapajós and displaced the jaguains living there as far as the Madeira River, so that troops were sent against them. Further conquests were largely unsuccessful and the large area was given up.

A peaceful trade-based relationship developed with the whites (raw materials such as salt, sugar and rubber were exchanged for tools, weapons and clothing). But the Munduruku territory has been shrinking since the late 19th century as a result of the massive extraction of rubber and other raw materials.

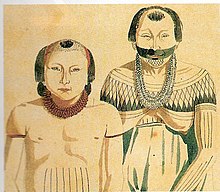

The self-designation Wuyjuyu or Weidyénye for the ethnic group, but not the language, means “ours”. Their neighbors, the Parintintin , gave them the name Munduruku, which means "red ants" and refers to their way of attacking as a large army. They are also known as caras pretas (dark faces ) because they have the custom of tattooing the face and body in thick lines.

In June 2013, a group of armed Mukuruku demonstrating on behalf of their cause was prevented by police from entering the Palace of the Presents in Brasilia.

A dam project on the rio Tapajós , one of the great tributaries of the Amazon, which threatened 200,000 hectares of jungle, failed due to the resistance of the Mundukuru . They received support from Catholic bishops. In 2016 the project associated with corruption scandals was canceled.

language

The Munduruku speak Mundurukú , a language of the Tupí language family , whose idioms, u. a. the better known Guaraní , one of the most common Indian languages in South America (for history see Tupí in the narrower sense).

The language situation is relatively stable today. Only group members who live in villages near the city and young adults who have already settled in the city speak Portuguese. Most of the elderly, women and children, as well as all those living in isolated villages, are monolingual in their autochthonous language.

According to French scholars, the Munduruku have a restricted vocabulary for numbers. You have z. B. no numerals for numbers greater than 5, but can make estimates and approximate arithmetic operations with larger quantities that are relatively accurate. Therefore, they have become an object of study for the exploration of mathematical thinking. With the help of suitable examination programs on the laptop, a fundamentally logarithmic mathematical thought structure of humans could be proven with them .

Regional groups

Regional groupings are:

- Tapajóz River Group (on both sides of the Tapajóz)

- Madeira River Mundurucú (depending on the Canumá)

- Xingú River Mundurucú ("Curuaya")

- Juruena River Mundurucú (Njambikwaras, controversial)

- Wiaunyen (possibly another group of the Mundurucú)

although it is doubtful whether this classification is correct, presumably the Njambikwara are not Mundurucú and the Wiaunyen are another sub-tribe of the Mundurucú.

population

(Increase in population before / during the conquests)

- 1820: 18,000 - 40,000 (travel report by the botanist Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius )

- 1877: 21 villages, 18,910 inhabitants (Tocantins)

- 1900: 37 communities, 1,400 inhabitants (Campana)

- 2004: 7,000 (Society for Threatened Peoples)

- 2009: approx. 11,000 (National Health Authority)

Military organization, warfare, and war customs

Warriors were accompanied by women and children in support. Before the start of a war expedition (usually in the dry season in summer) a staff was passed into the warrior's house and each participating warrior scratched a line in this staff, this is like a ritual pledge of loyalty to the war leader. Women did not take part in combat operations, but apparently tried to catch the opponents' arrows. The war leader stood behind the battlefield and "directed" the battle by means of signals. If a warrior was wounded, his name was not pronounced for a year and he was “thought” to be dead, after which a festival was held for his reintegration into the community. Women prisoners of war married Munduruku men, captive children were adopted, and the heads of the men killed were kept as trophies. The spread of cannibalism is scientifically controversial (cf. Strömer pro, Kruse contra).

Way of settlement

It is assumed that village buildings are open around a plaza (Tocantins and Farabee), and that scattered building is documented (Bates), or row-like building around a clearing (Martius). There are separate men's houses (fork construction) for the warriors and unmarried people, some of them particularly large, 100 m long (tocantins). Women are not allowed in there. Rectangular, windowless apartment buildings with low walls and high roofs were built as residential buildings. Every family has their own fireplace in it. How many lived in one house is unclear.

Economy

The Munduruku hunt tapirs and crocodiles, using bows with poison arrows as weapons. In addition, fish are caught in nets and berries, roots and fruits are collected. The predominant economic forms are the cultivation of cultivated plants such as sweet potatoes, tobacco, rice and bananas, as well as livestock. The preparation of the food is women's work.

Tools and utensils

The Munduruku make low-quality ceramics such as vases, baskets made of tendrils and straw, and various weapons. These include bows with arrows made of reed and wood, some with poisoned tips, spears, axes and "swords" made of bamboo. Stone objects also served as weapons in the past, but are now only used as children's toys.

trade

Despite hostility to the neighbors, there is trade in feather ornaments. Presumably, there is also economic dependency on sources of poison for arrow use.

dress

Everyday clothing consists of triangular penis strands (cover) made of wool; For rites, very fine and high-quality feather clothing is made for different parts of the body.

The Munduruku, along with the Mauhé, were among the greatest feather artists in Amazonia. The numerous feather works include, for example, feather bonnets with neck feathers, cape-like feather strands, feather mosaics and feather scepter worn by leaders. Typical here is the combination of red, yellow and black feathers, the so-called Tupí color combination. Most of the feathers used in the feather headdress come from parrots that the Munduruku keep in cages. After the birds have been plucked, the feathers are first sorted by color in baskets or palm tubes. Ara feathers were used almost exclusively, but also feathers from the red-billed hokko and, more rarely, from the trumpeter bird . Usually only yellow, red, blue and black feathers were used, while brown and white are extremely rare. It is said that the Munduruku were also able to change the color of the feathers on living birds. For this purpose, the bird was plucked and its skin was rubbed with a frog secretion, which caused the feathers to grow back in a different color. Often the color changed from green to yellow. In order to produce the feather ornaments, the feathers were usually attached to a mesh fabric, whereby the attachments of large feathers are often covered by rosettes made of small feathers. Effects are achieved through alternating colors. The feather headdress was an integral part of the ritual cycle around headhunting . Feather headdresses were also stolen from the enemy and traded on like their own.

However, knowledge of the manufacture and use of traditional feather ornaments has disappeared for over 100 years.

Tattoos and body paints

The body painting consists of widely spaced, parallel lines that are arranged vertically on the limbs and torso, occasionally also horizontally. Until the 1940s, men and women wore tattoos that were done from the age of six or seven.

Social organization

The Munduruku traditionally have a patrilineal kinship system with matrilocalism . About 38 clans, the members of which are associated with plants and animals from which they are named, each belong to one of two exogamous sub-tribes, the "red half" and the "white half". Polygamy ( levirate marriage ) is practiced by men of higher rank. Girls can be engaged to older warriors at an early age, even if the marriage does not come into force until after puberty. Until then, the warrior will take care of the girl's family. The accommodation is matrilocal: a young warrior can distinguish himself through several years of service with the family of the betrothed. The married warrior then joins the father-in-law's household. In the case of adultery, the guilty person is expelled from the tribe.

Cultural elements

Tattoos (parallel lines), feather headdresses, celebrations for fertility and earlier also various aspects of warfare (rituals for warrior initiation, warrior house ...); various cosmogonies and mythologized problems that can arise in the family ( incest , etc.). Shamans heal and regulate the course of life.

Religious ceremonies

When a member of the tribe dies, several rites are performed. The relatives on the mother's side cut their hair, dye their faces black, and complain for a while. The dead are buried with bent knees, wrapped in a hammock and provided with small grave goods, in a cylindrical grave under the house. The skeletons of high-ranking men are dug up again and burned when the flesh rots. Your ashes are buried in a jar. If a warrior dies on a distant battlefield, only his head is taken and given to a female relative. It is displayed on a pedestal with weapons and ornaments. A shaman plays isolated songs on the holy trumpet and a festival is held in honor of the dead. This is repeated for four years.

Every winter, alternating festivals to achieve success in hunting and fishing are celebrated, a shaman plays holy songs and a good warrior and singer leads the festival. Similar festivals are reported for corn and cassava. Various dance ceremonies under the full moon. At a festival, sexual intercourse is ritual; there are also celebrations for trees and men.

Shamanism and magic

The shaman's duties are to heal the sick and determine the best time for war and find sorcerers. Disease is viewed as a hex or a worm within a person that needs to be blown out.

mythology

Creator god and cultural hero is Karusakaibu (various spellings); his wife is Sikrida, a Mundurucú. The eldest son is Korumtau and the second son Anukaite. Karusakaibu's helper is Daiiru - an armadillo. The conflicts within the family (enmities, incest, ...) are processed mythologically in the family of the Creator God.

- Creation

There are several creation myths:

- Karusakaibu made the world but not people. Daiiru became defiant and had to go into a hole in the ground, then Karusakaibu stomped on the ground and Daiiru was blown out of the hole by the draft. He reported that people live underground in a world that is mirrored to the world. A net was held down for them and half the people climbed up; then the net tore and half of the people still live in this world. The moon and the sun shine there when they do not shine unearthly.

- Another version reports that people of color also climbed it. Karusakaibu as a cultural hero taught the cultivation of the plants and also the drawing of the rock art that you sometimes find.

Yet another version tells of a world in which men had the way of life of women and vice versa. The women discovered holy trumpets and played them secretly in the forest. When the men discovered this, they adopted the women's way of life and banished women from their homes, etc.

- An apocalyptic myth reports that the sun fell on earth and killed all living things. The Creator sent a vulture to see if the earth had cooled, but it ate the corpses. Then after four days he sent a raven, but it ate the charred buds of the trees. Another four days later he sent a pigeon to bring the earth back with its claws. Then the Creator came down to earth and made people and animals anew from the potter's clay.

- cosmology

- The Creator God created the sun from a person who had red eyes and long, white hair. The moon was transformed from a virgin who had white skin. Solar eclipses are interpreted as large fires on the sun that sweep across the surface of the sun. The shaman then sends a fragment of a ferrous meteorite ("yakpu") to the sun to free it. Then the yakpu falls back down to the earth as a ball of fire and after cooling down the shaman takes it back until the next darkness.

Web links

literature

- Donald Horton: The Mundurucu. In: Handbook of South American Indians. Volume 3, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington DC 1948. (Reprint: Cooper Square Publ., New York 1963, pp. 271–283)

- RI Murphy: Headhunter's heritage. Social and economic change among the Mundurucu indians. University of California Press, Berkeley 1960.

- Ilse Bearth-Braun: Mundurukú. Encounters in the Amazon. Hänssler, Neuhausen / Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7751-1727-X .

- Johannes Chrysostomus Stroemer: The language of the Munduruku. Dictionary, grammar, etc. Texts e. Indian idioms at Upper Tapajoz, Amazon region. Anthropos, Mödling b. Vienna 1932.

- Gerhard Strömer: The Mundurukú on the upper Tapajoz in the Amazon region, central Brazil. Studies and Research on business u. Ethnology e. south american. Indian people. Dissertation. Berlin 1942.

- W. Kapfhammer: The dance of the heads. The Munduruku in the 19th century. In: Claudia Augustat (ed.): Out of Brazil. Exhibition catalog of the Museum für Völkerkunde, Vienna. Vienna 2012, pp. 47–57.

- K. Kästner: Amazonia - Indians of the rainforests and savannahs. Accompanying publication to the special exhibition of the Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden. 2009.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b K. Kästner: Amazonia - Indians of the rainforests and savannahs . Ed .: Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden. 2009, p. 102-105 .

- ↑ Munduruku. ( Memento of December 23, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) In: Linguamón. Languages of the world. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ↑ The police prevent Munduruku Indians from storming the Palácio do Planalto, the presidential palace in Brasilia. ( Memento from January 4, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: Focus online. June 12th, 2013.

- ↑ Documentary on the resistance of the Munduruku , accessed September 3, 2018.

- ↑ Mundurukú. In: Ethnologue . Retrieved January 29, 2014 .

- ↑ Alex Bellos Riley: Alex's adventures in numberland. London: Bloomsbury, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4088-0959-4 .

- ↑ Holger Dambeck: The logarithm slumbers deep within us. In: mirror-online. Retrieved February 1, 2009 .

- ^ P. Pica, Cathy Lemer, V. Izard, S. Dehaene: Exact and approximate Arithmetic in an Amazonian Indigenous Group. In: Science. Volume 306, 2004, pp. 499-503. (www.sciencemag.org)

- ↑ Joh. Bapt. from Spix, Carl Friedr. Phil. Von Martius: Journey in Brazil in the years 1817-1820. Munich 1823–1831.

- ^ Fundação Nacional de Saúde. Edital de chamamento público Nº 23/2009 (PDF) ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b Donald Horton: The Mundurucu . In: JH Steward (Ed.): Handbook of South American Indians . tape 3 : The Tropical Forest Tribes . Cooper Square publishers, New York 1963, pp. 272-282 .

- ^ A. Schlothauer: Munduruku and Apiaká Featherwork in the Johann Natterer Collection . Ed .: Weltmuseum Wien. 2014, p. 152-153 .

- ^ W. Kapfhammer: The dance of the heads. The Munduruku in the 19th century . In: Claudia Augustat (Ed.): Out of Brazil - Exhibition catalog of the Museum für Völkerkunde, Vienna . Vienna 2012, p. 47-57 .

- ↑ A. Schlothauer: Munduruku feather headdress in the Musée Savoisien in Chambery . In: Art & Context . No. 2/2014 , 2014, p. 25-29 .

- ↑ The Mundurucú: Tattooed Warriors of the Amazon Jungle by Lars Krutak. Retrieved January 31, 2017 .

- ↑ Robert F. Murphy: Matrilocality and Patrilineality in Mundurucu Society. In: American Anthropologist. Vol. 58, No. 3, 1956, pp. 414-433.

- ↑ Brazil portal